DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~, Tt'tll\ E . a .. L Worilbl)Oc

"THE JOURNAL.OF ~, tt'tll\e ... A.. L WORilbl)oc ~.l)u AND Ok1 ERATORSJ.ljiru OFFICIAL PUBLICATION _.. INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF ElECTRICAL WORKER$--.- _ ~ -~- -' (:\ /~ //1 \"- II .0;,)[1 I October, 1920 !11AXADYI AFFILIATED WITH THE . AMERICAN 'FEDERATION OF LABOR IN ALL ITS D E PA R T M E.N T S II atLL II DEVOTED TO THE CAUSE OF ORGANIZED LABOR \ II 302~ "OUR FIXTURES ARE LIGHTING HOMES FROM COAST TO COAST" We have a dealer's proposition that will interest you. Our prices are low and quality of the best. Catalogue No. 18 free .ERIE FIXTURE SUPPLY CO. 359 West 18th St.. Erie. Pa. Blake Insulated Staples BLAKE 6 "3 . 4 Si;oel l Signal & Mfg. Co. n:t,· BOSTON :.: MASS. Pat. Nov. 1900 BLAKE TUBE FLUX Pat. July 1906 Tf T Convenient to carry and to use. Will not collect dust and dirt nor K'et on tools in kit. You can get the solder ina' Dux: just where YOD want it and in just tho desired Quantity. Named shoes are frequently made in non-union factories DO NOT BUY ANY SHOE No matter what its name, uniess it bears a plain and readable iinpression of the UNION STAMP All shoes without the UNION STAMP are always Non-Union Do not accept any excuse for absence of the UNION STAMP BOOT AND SHOE WORKERS' UNION II 246 Summer Street, Boston. Mass- I UCollis Lovely, General Pres. Charles L. Baine, General Sec.-Treall. , When 'writing mention The Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators. The Journal of Electrical Workers and Operators OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE International Brotherhood of Electrical Workera Affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and all Its DOepartments. -

Court-Packing and Compromise Barry Cushman

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Constitutional Commentary 2013 Court-Packing and Compromise Barry Cushman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cushman, Barry, "Court-Packing and Compromise" (2013). Constitutional Commentary. 78. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Constitutional Commentary collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !!!CUSHMAN-291-COURT-PACKING AND COMPROMISE.DOC (DO NOT DELETE) 8/9/2013 2:15 PM Articles COURT-PACKING AND COMPROMISE Barry Cushman* The controversy precipitated by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Court-packing Plan is among the most famous and frequently discussed episodes in American constitutional history. During his first term as President, Roosevelt had watched with mounting discontent as the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional a series of measures central to his New Deal. Aging justices whom Roosevelt considered reactionary and out of touch had struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act (“NIRA”), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (“AAA”), federal railway pension legislation, federal farm debt relief legislation, critical portions of the Administration’s energy policy, and state minimum wage legislation for women. In the spring of 1937 the Court would be ruling on the constitutionality of such major statutes as the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) and the Social Security Act (“SSA”), and a number of Roosevelt advisors doubted that the Court as then comprised would uphold those measures. -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

Tip O'neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 28 Issue 1 Assembled Pieces: Selected Writings by Shaun Article 14 O'Connell 11-18-2015 Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003) Shaun O’Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation O’Connell, Shaun (2015) "Tip O’Neill: Irish-American Representative Man (2003)," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol28/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tip O’Neill: Irish American Representative Man Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Man of the House as he aptly called himself in his 1987 memoir, stood as the quintessential Irish American representative man for half of the twentieth century. O’Neill, often misunderstood as a parochial, Irish Catholic party pol, was a shrewd, sensitive, and idealistic man who came to stand for a more inclusive and expansive sense of his region, his party, and his church. O’Neill’s impressive presence both embodied the clichés of the Irish American character and transcended its stereotypes by articulating a noble vision of inspired duty, determined responsibility, and joy in living. There was more to Tip O’Neill than met the eye, as several presidents learned. -

Seventy-First Congress

. ~ . ··-... I . •· - SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS ,-- . ' -- FIRST SESSION . LXXI-2 17 , ! • t ., ~: .. ~ ). atnngr tssinnal Jtcnrd. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SEVENTY-FIRST CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Couzens Harris Nor beck Steiwer SENATE Dale Hastings Norris Swanson Deneen Hatfield Nye Thomas, Idaho MoNDAY, April 15, 1929 Dill Hawes Oddie Thomas, Okla. Edge Hayden Overman Townsend The first session of the Seventy-first Congress comm:enced Fess Hebert Patterson Tydings this day at the Capitol, in the city of Washington, in pursu Fletcher Heflin Pine Tyson Frazier Howell Ransdell Vandenberg ance of the proclamation of the President of the United States George Johnson Robinson, Ark. Wagner of the 7th day of March, 1929. Gillett Jones Sackett Walsh, Mass. CHARLES CURTIS, of the State of Kansas, Vice President of Glass Kean Schall Walsh, Mont. Goff Keyes Sheppard Warren the United States, called the Senate to order at 12 o'clock Waterman meridian. ~~~borough ~lenar ~p~~~~;e 1 Watson Rev. Joseph It. Sizoo, D. D., minister of the New York Ave Greene McNary Smoot nue Presbyterian Church of the city of Washington, offered the Hale Moses Steck following prayer : Mr. SCHALL. I wish to announce that my colleag-ue the senior Senator from Minnesota [Mr. SHIPSTEAD] is serio~sly ill. God of our fathers, God of the nations, our God, we bless Thee that in times of difficulties and crises when the resources Mr. WATSON. I desire to announce that my colleague the of men shrivel the resources of God are unfolded. Grant junior Senator from Indiana [Mr. RoBINSON] is unav.oidably unto Thy servants, as they stand upon the threshold of new detained at home by reason of important business. -

May 29, 2012 Chairman Fred Upton House Energy and Commerce

May 29, 2012 Chairman Fred Upton Ranking Member Henry Waxman House Energy and Commerce Committee House Energy and Commerce Committee 2125 Rayburn House Office Building 2322A Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairman Upton and Ranking Member Waxman: The undersigned organizations concerned with openness and accountability are writing to urge you to remove or substantially narrow a provision of H.R. 5651, the Food and Drug Administration Reform Act of 2012, that needlessly prevents the public from having access to potentially important health and safety information and that could greatly diminish the public’s access to information about the work of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Section 812 of H.R. 5651 allows the FDA to deny the public access to information relating to drugs obtained from a federal, state, local, or foreign government agency, if the agency has requested that the information be kept confidential. As introduced, Section 708 of S. 3187, the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, contained similar language. The Senate accepted an amendment to the provision offered by Senator Leahy (D-VT) that limits the scope to information voluntarily provided by foreign governments, requires that the request to keep the information confidential be in writing, and, unless otherwise agreed upon, specifies a time frame after which the information will no longer be treated as confidential. We understand that Congress intends the language to promote the sharing of drug inspection information by foreign governments with the FDA. However, the FDA does not need this authority because the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) already provides exemptions to protect against the release of many law enforcement records; confidential, commercial information; and trade secrets. -

Download History of the House Page Program

HISTORY OF THE HOUSE PAGE PROGRAM CONTENTS Introduction 1 Page Origins 2 Page Responsibilities 7 Representatives as Role Models and Mentors 10 Page Traditions 12 Breaking Down Racial and Gender Barriers 17 Pages and Publicity 19 Schools, Dorms, and Reforms 21 Pages and the Communications Revolution 26 The End of the House Page Program 28 Notes 30 Pages wore lapel pins to identify themselves during work or to affiliate themselves with the Page program. Left, a National Fraternity of Pages pin owned by Glenn Rupp, a House Page in the 1930s, includes the date 1912, which may indicate the founding date of the organization. Middle, a Page pin from 1930 is more elaborately designed than the average uniform lapel pin and features an enamel shield with links attaching a pendant that indicates the date of service. Right, a pin from 100th Congress (1987– 1989) has a House seal in the center and is similar to those worn by Members on their own lapels. Page Pins, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives i House Pages pose for a class photo on the East Front of the Capitol. Class Photo from The Congressional Eagle Yearbook, 2007, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives For more than two centuries, young people served as Pages in the U.S. House of Representatives and enjoyed an unparalleled opportunity to observe and participate in the legislative process in “the People’s House.” Despite the frequent and colossal changes to America’s national fabric over that period, the expectations and experiences of House Pages, regardless of when they served, have been linked by certain commonalities—witnessing history, interacting with Representatives, and taking away lifelong inspiration to participate in civic life. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

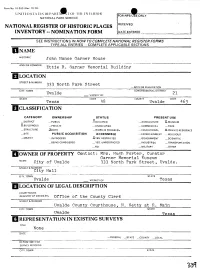

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form Date Entered

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^jt UNHLDSTAn.S DLPARTP^K'T Oh TUt, INILR1OR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC John Nance Garner House AND/OR COMMON Ettie R. Garner Memorial Buildinp [LOCATION STREET& NUMBFR 333 North Park Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 21 Uvalde VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Uvalde 463 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL __PARK —STRUCTURE J&BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: Mrs. Hugh Porter, Curator Garner Memorial Museum NAME City of Uvalde 333 North Park Street, Uvalde STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde VICINITY OF Texas [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC office of the County Clerk STREETS NUMBER Uvalde County Courthouse, N. Getty at E. Main CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE ^LcOOD —RUINS ?_ALTERED _MOVED DATE——————— _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1920 until his wife's death in 1952, Garner made his permanent home in this two-story, H-shaped, hip-roofed, brick house, which was designed for him by architect Atlee Ayers. -

2. Krehbiel and Wiseman

Joe Cannon and the Minority Party 479 KEITH KREHBIEL Stanford University ALAN E. WISEMAN The Ohio State University Joe Cannon and the Minority Party: Tyranny or Bipartisanship? The minority party is rarely featured in empirical research on parties in legis- latures, and recent theories of parties in legislatures are rarely neutral and balanced in their treatment of the minority and majority parties. This article makes a case for redressing this imbalance. We identified four characteristics of bipartisanship and evaluated their descriptive merits in a purposely hostile testing ground: during the rise and fall of Speaker Joseph G. Cannon, “the Tyrant from Illinois.” Drawing on century- old recently discovered records now available in the National Archives, we found that Cannon was anything but a majority-party tyrant during the important committee- assignment phase of legislative organization. Our findings underscore the need for future, more explicitly theoretical research on parties-in-legislatures. The minority party is the crazy uncle of American politics, showing up at most major events, semiregularly causing a ruckus, yet stead- fastly failing to command attention and reflection. In light of the large quantity of new research on political parties, the academic marginalization of the minority party is ironic and unfortunate. It appears we have an abundance of theoretical and empirical arguments about parties in legislatures, but the reality is that we have only slightly more than half of that. The preponderance of our theories are about a single, strong party in the legislature: the majority party. A rare exception to the majority-centric rule is the work of Charles Jones, who, decades ago, lamented that “few scholars have made an effort to define these differences [between majority and minority parties] in any but the most superficial manner” (1970, 3).