2. Krehbiel and Wiseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C RS Report for Congress

Order Code RL30666 C RS Report for Congress The Role of the House Minority Leader: An Overview Updated December 12, 2006 Walter J. Oleszek Senior Specialist in the Legislative Process Government and Finance Division Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress House Minority Leader Summary The House minority leader is head of the "loyal opposition." The party's nominee for Speaker, the minority leader is elected every two years by secret ballot of his or her party caucus or conference. The minority leader's responsibilities involve an array of duties. Fundamentally, the primary goal of the minority leader is to recapture majority control of the House. In addition, the minority leader performs important institutional and party functions. From an institutional perspective, the rules of the House assign a number of specific responsibilities to the minority leader. For example, Rule XII, clause 6, grant the minority leader (or his designee) the right to offer a motion to recommit with instructions; Rule II, clause 6, states the Inspector General shall be appointed by joint recommendation of the Speaker, majority leader, and minority leader; and Rule XV, clause 6, provides that the Speaker, after consultation with the minority leader, may place legislation on the Corrections Calendar. The minority leader also has other institutional duties, such as appointing individuals to certain federal entities. From a party perspective, the minority leader has a wide range of partisan assignments, all geared toward retaking majority control of the House. Five principal party activities direct the work of the minority leader. First, he or she provides campaign assistance to party incumbents and challengers. -

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Updated January 25, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30857 Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2021 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. A Member normally votes for the candidate of his or her own party conference but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House because of vacancies, absentees, or Members answering “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 117th Congresses), a Speaker was elected six times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Five such elections occurred since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent three, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. -

In April 1917, John Sharp Williams Was Almost Sixty-Three Years Old, and He Could Barely Hear It Thunder

1 OF GENTLEMEN AND SOBs: THE GREAT WAR AND PROGRESSIVISM IN MISSISSIPPI In April 1917, John Sharp Williams was almost sixty-three years old, and he could barely hear it thunder. Sitting in the first row of the packed House chamber, he leaned forward, “huddled up, listening . approvingly” as his friend Woodrow Wilson asked the Congress, not so much to declare war as to “accept the status of belligerent” which Germany had already thrust upon the reluctant American nation. No one knew how much of the speech the senior senator from Mississippi heard, though the hand cupped conspicuously behind the right ear betrayed the strain of his effort. Frequently, whether from the words themselves or from the applause they evoked, he removed his hand long enough for a single clap before resuming the previous posture, lest he lose the flow of the president’s eloquence.1 “We are glad,” said Wilson, “now that we see the facts with no veil of false pretense about them, to fight thus for the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of its peoples, the German peoples included; for the rights of nations, great and small, and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life and of obedience. The world must be made safe for democracy.” That final pregnant phrase Williams surely heard, for “alone he began to applaud . gravely, emphatically,” and continued until the entire audience, at last gripped by “the full and immense meaning” of the words, erupted into thunderous acclamation.2 Scattered about the crowded chamber were a handful of dissenters, including Williams’s junior colleague from Mississippi, James K. -

Union Calendar No. 607

1 Union Calendar No. 607 110TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 110–934 REPORT ON THE LEGISLATIVE AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS DURING THE 110TH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2009.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 79–006 WASHINGTON : 2009 VerDate Nov 24 2008 22:51 Jan 06, 2009 Jkt 079006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR934.XXX HR934 sroberts on PROD1PC70 with HEARING E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York, Chairman FORTNEY PETE STARK, California JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan WALLY HERGER, California JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington DAVE CAMP, Michigan JOHN LEWIS, Georgia JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts SAM JOHNSON, Texas MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JERRY WELLER, Illinois XAVIER BECERRA, California KENNY C. HULSHOF, Missouri LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas RON LEWIS, Kentucky EARL POMEROY, North Dakota KEVIN BRADY, Texas STEPHANIE TUBBS JONES, Ohio THOMAS M. REYNOLDS, New York MIKE THOMPSON, California PAUL RYAN, Wisconsin JOHN B. LARSON, Connecticut ERIC CANTOR, Virginia RAHM EMANUEL, Illinois JOHN LINDER, Georgia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon DEVIN NUNES, California RON KIND, Wisconsin PAT TIBERI, Ohio BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey JON PORTER, Nevada SHELLY BERKLEY, Nevada JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland KENDRICK MEEK, Florida ALLYSON Y. SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania ARTUR DAVIS, Alabama (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:20 Jan 06, 2009 Jkt 079006 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\HR934.XXX HR934 sroberts on PROD1PC70 with HEARING LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL U.S. -

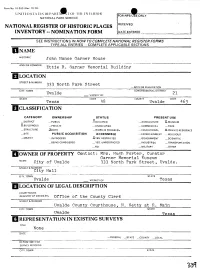

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form Date Entered

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^jt UNHLDSTAn.S DLPARTP^K'T Oh TUt, INILR1OR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC John Nance Garner House AND/OR COMMON Ettie R. Garner Memorial Buildinp [LOCATION STREET& NUMBFR 333 North Park Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 21 Uvalde VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Uvalde 463 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL __PARK —STRUCTURE J&BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: Mrs. Hugh Porter, Curator Garner Memorial Museum NAME City of Uvalde 333 North Park Street, Uvalde STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde VICINITY OF Texas [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC office of the County Clerk STREETS NUMBER Uvalde County Courthouse, N. Getty at E. Main CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE ^LcOOD —RUINS ?_ALTERED _MOVED DATE——————— _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1920 until his wife's death in 1952, Garner made his permanent home in this two-story, H-shaped, hip-roofed, brick house, which was designed for him by architect Atlee Ayers. -

Senate the Senate Met at 10:31 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MARCH 22, 2018 No. 50 Senate The Senate met at 10:31 a.m. and was from the State of Missouri, to perform the It will confront the scourge of addic- called to order by the Honorable ROY duties of the Chair. tion head-on and help save lives. For BLUNT, a Senator from the State of ORRIN G. HATCH, rural communities, like many in my Missouri. President pro tempore. home State of Kentucky, this is a big Mr. BLUNT thereupon assumed the deal. f Chair as Acting President pro tempore. The measure is also a victory for PRAYER f safe, reliable, 21st century infrastruc- The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY ture. It will fund long overdue improve- fered the following prayer: LEADER ments to roads, rails, airports, and in- Let us pray. land waterways to ensure that our O God, our Father, may life’s seasons The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- pore. The majority leader is recog- growing economy has the support sys- teach us that You stand within the tem that it needs. shadows keeping watch above Your nized. own. We praise You that You are our f Importantly, the bill will also con- tain a number of provisions to provide refuge and strength, a very present OMNIBUS APPROPRIATIONS BILL help in turbulent times. more safety for American families. It Lord, cultivate within our lawmakers Mr. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

4Z SAM RAYBURN: TRIALS OF A PARTY MAN DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Edward 0. Daniel, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1979 Daniel, Edward 0., Sam Rayburn: Trials of a Party Man. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1979, 330 pp., bibliog- raphy, 163 titles. Sam Rayburn' s remarkable legislative career is exten- sively documented, but no one has endeavored to write a political biography in which his philosophy, his personal convictions, and the forces which motivated him are analyzed. The object of this dissertation is to fill that void by tracing the course of events which led Sam Rayburn to the Speakership of the United States House of Representatives. For twenty-seven long years of congressional service, Sam Rayburn patiently, but persistently, laid the groundwork for his elevation to the speakership. Most of his accomplish- ments, recorded in this paper, were a means to that end. His legislative achievements for the New Deal were monu- mental, particularly in the areas of securities regulation, progressive labor laws, and military preparedness. Rayburn rose to the speakership, however, not because he was a policy maker, but because he was a policy expeditor. He took his orders from those who had the power to enhance his own station in life. Prior to the presidential election of 1932, the center of Sam Rayburn's universe was an old friend and accomplished political maneuverer, John Nance Garner. It was through Garner that Rayburn first perceived the significance of the "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" style of politics. -

Thomas Woodrow Wilson James Madison* James Monroe* Edith

FAMOUS MEMBERS OF THE JEFFERSON SOCIETY PRESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Thomas Woodrow Wilson James Madison∗ James Monroe∗ FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES Edith Bolling Galt Wilson∗ PRIME MINISTERS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM Margaret H. Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher∗ SPEAKERS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter UNITED STATES SENATORS Oscar W. Underwood, Senate Minority Leader, Alabama Hugh Scott, Senate Minority Leader, Pennsylvania Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, Virginia Willis P. Bocock, Virginia John S. Barbour Jr., Virginia Harry F. Byrd Jr., Virginia John Warwick Daniel, Virginia Claude A. Swanson, Virginia Charles J. Faulkner, West Virginia John Sharp Williams, Mississippi John W. Stevenson, Kentucky Robert Toombs, Georgia Clement C. Clay, Alabama Louis Wigfall, Texas Charles Allen Culberson, Texas William Cabell Bruce, Maryland Eugene J. McCarthy, Minnesota∗ James Monroe, Virginia∗ MEMBERS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Oscar W. Underwood, House Majority Leader, Alabama John Sharp Williams, House Minority Leader, Mississippi Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, Virginia Richard Parker, Virginia Robert A. Thompson, Virginia Thomas H. Bayly, Virginia Richard L. T. Beale, Virginia William Ballard Preston, Virginia John S. Caskie, Virginia Alexander H. H. Stuart, Virginia James Alexander Seddon, Virginia John Randolph Tucker, Virginia Roger A. Pryor, Virginia John Critcher, Virginia Colgate W. Darden, Virginia Claude A. Swanson, Virginia John S. Barbour Jr., Virginia William L. Wilson, West Virginia Wharton J. Green, North Carolina William Waters Boyce, South Carolina Hugh Scott, Pennsylvania Joseph Chappell Hutcheson, Texas John W. Stevenson, Kentucky Robert Toombs, Georgia Thomas W. Ligon, Maryland Augustus Maxwell, Florida William Henry Brockenbrough, Florida Eugene J. -

You're Fired! Boehner Succumbs to the Republican

September 28, 2015 You’re fired! Boehner succumbs to the Republican way of leadership by JOSHUA SPIVAK After years of threats, Republican House backbenchers have finally succeeded in effectively ousting House Speaker John Boehner. Boehner, who announced his impending resignation on September 25, joins what once was a very small club but is now growing every few years — the list of Republican congressional leaders who have been tossed to the side by their internal party dynamics. A look at their record shows that “you’re fired” is not just the favored phrase of their party’s current presidential front-runner. Boehner’s failure to maintain power mirrors some of recent predecessors. It is a bit surprising to see the successful coups, as the speaker of the House is easily the most powerful congressional job. Unlike the Senate majority leader, a powerful speaker can bend the House to his will. The roles of speaker and majority or minority leader were historically so powerful that John Barry, in his book on the Jim Wright speakership, The Ambition and the Power, compared a successful attack on the speaker or minority leader to regicide. And yet the Republicans have been very willing to launch these broadsides against their own party leaders. The most prominent example was former Speaker Newt Gingrich, who was credited with leading the Republicans back into the House majority after 40 years in the minority wilderness. But when trouble came, his party faithful were quick to turn. In 1997, other top leaders, including Representative Boehner of Ohio, looked to force out Gingrich. -

H. Doc. 108-222

SIXTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1921, TO MARCH 3, 1923 FIRST SESSION—April 11, 1921, to November 23, 1921 SECOND SESSION—December 5, 1921, to September 22, 1922 THIRD SESSION—November 20, 1922, to December 4, 1922 FOURTH SESSION—December 4, 1922, to March 3, 1923 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1921, to March 15, 1921 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—CALVIN COOLIDGE, of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ALBERT B. CUMMINS, 1 of Iowa SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—GEORGE A. SANDERSON, 2 of Illinois SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—DAVID S. BARRY, of Rhode Island SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—FREDERICK H. GILLETT, 3 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM TYLER PAGE, 4 of Maryland SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH G. ROGERS, of Pennsylvania DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BERT W. KENNEDY, of Michigan POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FRANK W. COLLIER ALABAMA Ralph H. Cameron, Phoenix Samuel M. Shortridge, Menlo Park REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Carl Hayden, Phoenix Oscar W. Underwood, Birmingham Clarence F. Lea, Santa Rosa J. Thomas Heflin, Lafayette ARKANSAS John E. Raker, Alturas REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS Charles F. Curry, Sacramento Julius Kahn, San Francisco John McDuffie, Monroeville Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock John I. Nolan, 9 San Francisco John R. Tyson, Montgomery Thaddeus H. Caraway, Jonesboro Mae E. Nolan, 10 San Francisco Henry B. Steagall, Ozark REPRESENTATIVES John A. Elston, 11 Berkeley Lamar Jeffers, 5 Anniston William J. Driver, Osceola James H. MacLafferty, 12 Oakland William B. Bowling, Lafayette William A. Oldfield, Batesville Henry E. Barbour, Fresno William B. -

Carrollton, Illinois, 1818-1968: an Album of Yesterday and Today

:arrollton, Illinois, 1818- .968: An Album of Yesterday ind Today. ILLINOIS HISTORICAL SURVEY 384 C I n i n An Album of Yesterday and Today UNIVERSITY OF " ILLI Y ' AiviPAlGN AT l & ILL HIST. SURVEY PREFACE This booklet has been prepared by the Carrollton Business and Professional Women's Club to commemo- rate Carrolton's Sesquicentennial. Obviously, we could not hope to compile a complete history of Carrollton in a matter of 30 days and as many pages, and so have designed an ALBUM OF TODAY AND YESTERDAY, using pictures and articles available to us. On our cover you see the monument erected in honor of our founder, Thomas Carlin, who was born near Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1786. In ls03, the family moved to Missouri, which was then Spanish territory. His father died there and Thomas came to Illinois and served as a Ranger in the War of 1812. Following the war he operated a ferry for four years opposite the mouth of the Missouri River, where he was married. In ISIS, he located on land which now forms a part of the City of Carrollton. In 1821, Greene County was created by an act of the legislature in session at Vandalia and Mr. Carlin, Thomas Rattan, John Allen, John Green and John Huitt, Sr. were appointed. commissioners to locale the the county seat. After a short meeting at the home of Isaac Pruitt, the commissioners mounted their horses and rode east to a promising location on land owned by Mr. Carlin. History has it that the group halted at a point later identified as being on the east side of the present public square in Carrollton and that John Allen paced about 50 yards to the west, drove a stake, and announced: "Here let the Courthouse be built." The town was named Carrollton after Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Mary land, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.