The Evolution of the Eyebrow Region of the Forehead, with Special Reference to the Excessive Supraorbital Development in the Neanderthal Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurocranial Histomorphometrics

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Neurocranial Histomorphometrics Lindsay Hines Trammell University of Tennessee-Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Trammell, Lindsay Hines, "Neurocranial Histomorphometrics. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1359 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Lindsay Hines Trammell entitled "Neurocranial Histomorphometrics." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Anthropology. Murray K. Marks, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Joanne L. Devlin, David A. Gerard, Walter E. Klippel, David G. Anderson (courtesy member) Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Neurocranial Histomorphometrics Lindsay Hines Trammell University of Tennessee-Knoxville, [email protected] This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

Lab Manual Axial Skeleton Atla

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES When studying the skeletal system, the bones are often sorted into two broad categories: the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. This lab focuses on the axial skeleton, which consists of the bones that form the axis of the body. The axial skeleton includes bones in the skull, vertebrae, and thoracic cage, as well as the auditory ossicles and hyoid bone. In addition to learning about all the bones of the axial skeleton, it is also important to identify some significant bone markings. Bone markings can have many shapes, including holes, round or sharp projections, and shallow or deep valleys, among others. These markings on the bones serve many purposes, including forming attachments to other bones or muscles and allowing passage of a blood vessel or nerve. It is helpful to understand the meanings of some of the more common bone marking terms. Before we get started, look up the definitions of these common bone marking terms: Canal: Condyle: Facet: Fissure: Foramen: (see Module 10.18 Foramina of Skull) Fossa: Margin: Process: Throughout this exercise, you will notice bold terms. This is meant to focus your attention on these important words. Make sure you pay attention to any bold words and know how to explain their definitions and/or where they are located. Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the axial skeleton. As you explore these bones in Visible Body’s app, also locate the bones and bone markings on any available charts, models, or specimens. You may also find it helpful to palpate bones on yourself or make drawings of the bones with the bone markings labeled. -

Single‑Staged Resections and 3D Reconstructions of the Nasion, Glabella, Medial Orbital Wall, and Frontal Sinus and Bone

OPEN ACCESS Editor: James I. Ausman, MD, PhD For entire Editorial Board visit : University of California, Los http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com Angeles, CA, USA SNI: Skull Base, a supplement to Surgical Neurology International Case Report Single‑staged resections and 3D reconstructions of the nasion, glabella, medial orbital wall, and frontal sinus and bone: Long‑term outcome and review of the literature Jeremy Ciporen, Brandon P. Lucke‑Wold1, Gustavo Mendez2, Anton Chen3, Amit Banerjee4, Paul T. Akins4, Ben J. Balough3 Department of Neurological Surgery, and 2Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, 1Department of Neurosurgery, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia, 3Departments of ENT, and 4Neurosurgery, Kaiser Permanente, Sacramento, California, USA E‑mail: *Jeremy Ciporen ‑ [email protected]; Brandon P. Lucke‑Wold ‑ [email protected]; Gustavo Mendez ‑ [email protected]; Anton Chen ‑ [email protected]; Amit Banerjee ‑ [email protected]; Paul T. Akins ‑ [email protected]; Ben J. Balough ‑ [email protected] *Corresponding author Received: 11 March 16 Accepted: 10 September 16 Published: 26 December 16 Abstract Background: Aesthetic facial appearance following neurosurgical ablation of frontal fossa tumors is a primary concern for patients and neurosurgeons alike. Craniofacial reconstruction procedures have drastically evolved since the development of three‑dimensional computed tomography imaging and computer‑assisted programming. Traditionally, two‑stage approaches for resection and reconstruction were used; however, these two‑stage approaches have many complications including cerebrospinal fluid leaks, necrosis, and pneumocephalus. Case Description: We present two successful cases of single‑stage osteoma resection and craniofacial reconstruction in a 26‑year‑old female and 65‑year‑old male. -

Anatomy of the Periorbital Region Review Article Anatomia Da Região Periorbital

RevSurgicalV5N3Inglês_RevistaSurgical&CosmeticDermatol 21/01/14 17:54 Página 245 245 Anatomy of the periorbital region Review article Anatomia da região periorbital Authors: Eliandre Costa Palermo1 ABSTRACT A careful study of the anatomy of the orbit is very important for dermatologists, even for those who do not perform major surgical procedures. This is due to the high complexity of the structures involved in the dermatological procedures performed in this region. A 1 Dermatologist Physician, Lato sensu post- detailed knowledge of facial anatomy is what differentiates a qualified professional— graduate diploma in Dermatologic Surgery from the Faculdade de Medician whether in performing minimally invasive procedures (such as botulinum toxin and der- do ABC - Santo André (SP), Brazil mal fillings) or in conducting excisions of skin lesions—thereby avoiding complications and ensuring the best results, both aesthetically and correctively. The present review article focuses on the anatomy of the orbit and palpebral region and on the important structures related to the execution of dermatological procedures. Keywords: eyelids; anatomy; skin. RESU MO Um estudo cuidadoso da anatomia da órbita é muito importante para os dermatologistas, mesmo para os que não realizam grandes procedimentos cirúrgicos, devido à elevada complexidade de estruturas envolvidas nos procedimentos dermatológicos realizados nesta região. O conhecimento detalhado da anatomia facial é o que diferencia o profissional qualificado, seja na realização de procedimentos mini- mamente invasivos, como toxina botulínica e preenchimentos, seja nas exéreses de lesões dermatoló- Correspondence: Dr. Eliandre Costa Palermo gicas, evitando complicações e assegurando os melhores resultados, tanto estéticos quanto corretivos. Av. São Gualter, 615 Trataremos neste artigo da revisão da anatomia da região órbito-palpebral e das estruturas importan- Cep: 05455 000 Alto de Pinheiros—São tes correlacionadas à realização dos procedimentos dermatológicos. -

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

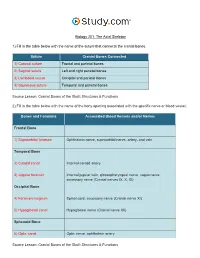

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

The Frontal Bone As a Proxy for Sex Estimation in Humans: a Geometric

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 The frontal bone as a proxy for sex estimation in humans: a geometric morphometric analysis Lucy Ann Edwards Hochstein Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hochstein, Lucy Ann Edwards, "The frontal bone as a proxy for sex estimation in humans: a geometric morphometric analysis" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 1749. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1749 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FRONTAL BONE AS A PROXY FOR SEX ESTIMATION IN HUMANS: A GEOMETRIC MORPHOMETRIC ANALYSIS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Anthropology in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Lucy A. E. Hochstein B.A., George Mason University, 2009 May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completing a master’s thesis was the most terrifying aspect of graduate school and I must acknowledge the people and pets that helped me on this adventure. I could not have asked for a better committee chair than Dr. Ginny Listi, who stuck by me when everything fell apart and was always willing to offer support and help me find solutions. -

A Heads up on Craniosynostosis

Volume 1, Issue 1 A HEADS UP ON CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS Andrew Reisner, M.D., William R. Boydston, M.D., Ph.D., Barun Brahma, M.D., Joshua Chern, M.D., Ph.D., David Wrubel, M.D. Craniosynostosis, an early closure of the growth plates of the skull, results in a skull deformity and may result in neurologic compromise. Craniosynostosis is surprisingly common, occurring in one in 2,100 children. It may occur as an isolated abnormality, as a part of a syndrome or secondary to a systemic disorder. Typically, premature closure of a suture results in a characteristic cranial deformity easily recognized by a trained observer. it is usually the misshapen head that brings the child to receive medical attention and mandates treatment. This issue of Neuro Update will present the diagnostic features of the common types of craniosynostosis to facilitate recognition by the primary care provider. The distinguishing features of other conditions commonly confused with craniosynostosis, such as plagiocephaly, benign subdural hygromas of infancy and microcephaly, will be discussed. Treatment options for craniosynostosis will be reserved for a later issue of Neuro Update. Types of Craniosynostosis Sagittal synostosis The sagittal suture runs from the anterior to the posterior fontanella (Figure 1). Like the other sutures, it allows the cranial bones to overlap during birth, facilitating delivery. Subsequently, this suture is the separation between the parietal bones, allowing lateral growth of the midportion of the skull. Early closure of the sagittal suture restricts lateral growth and creates a head that is narrow from ear to ear. However, a single suture synostosis causes deformity of the entire calvarium. -

Bone-Axial Skeleton

BIO 176: Human Anatomy Lab Bone Practical: Lecture Bone-Axial Skeleton Speaker: Heidi Peterson What you will see in the following presentation are all of the bones and features and markings you will need to know for your upcoming practical. We are going to start with the skull. On the skull you will see an anterior view, which is like looking at somebody face to face. On the anterior view the use of your regional terms is going to be necessary. You learned them for a reason and they are going to help you with bones. The first bone you are going to see is your forehead, but it is actually called the frontal bone. The next bone you see is the nasal bone. It also forms the bridge of your nose. You might know it as the cheek bone, but anatomically correct it is called the zygomatic. If you feel in between your two nostrils it might seem strange, but you are going to find a bony protuberance that is called the vomer. The vomer is the bone that gives shape to your lip. That little frenulum comes from the vomer. Also in the skull you will find two big jaw bones. The top jaw bone is the Maxillae. And the bottom jaw bone is the Mandible. There will be features on each of these bones but we will talk about those in just a bit. Starting with the markings or features you will see a circle around something above the orbit of your eye. Anything that is above something anatomically is called superior or supra. -

Crista Galli (Part of Cribriform Plate of Ethmoid Bone)

Alveolar margins alveolar margins coronal suture coronal suture coronoid process crista galli (part of cribriform plate of ethmoid bone) ethmoid bone ethmoid bone ethmoid bone external acoustic meatus external occipital crest external occipital protuberance external occipital protuberance frontal bone frontal bone frontal bone frontal sinus frontal squama of frontal bone frontonasal suture glabella incisive fossa inferior nasal concha inferior nuchal line inferior orbital fissure infraorbital foramen internal acoustic meatus lacrimal bone lacrimal bone lacrimal fossa lambdoid suture lambdoid suture lambdoid suture mandible mandible mandible mandibular angle mandibular condyle mandibular foramen mandibular notch mandibular ramus mastoid process of the temporal bone mastoid process of the temporal bone maxilla maxilla maxilla mental foramen mental foramen middle nasal concha of ethmoid bone nasal bone nasal bone nasal bone nasal bone occipital bone occipital bone occipital bone occipitomastoid suture occipitomastoid suture occipitomastoid suture occipital condyle optic canal optic canal palatine bone palatine process of maxilla parietal bone parietal bone parietal bone parietal bone perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone pterygoid process of sphenoid bone sagittal suture sella turcica of sphenoid bone Sphenoid bone (greater wing) spehnoid bone (greater wing) sphenoid bone (greater wing) sphenoid bone (greater wing) sphenoid sinus sphenoid sinus squamous suture squamous suture styloid process of temporal bone superior nuchal line superior orbital fissure supraorbital foramen (notch) supraorbital margin sutural bone temporal bone temporal bone temporal bone vomer bone vomer bone zygomatic bone zygomatic bone. -

Anatomy Lab: the Skeletal System Part I: Vertebrae and Thoracic Cage

ANA Lab: Bone 1 Anatomy Lab: The skeletal system Part I: Vertebrae and Thoracic cage Spine (Vertebrae) Body Vertebral arch Vertebral canal Pedicle Lamina Spinous process Transverse process Sup. articular facets Inf. articular facets Sup. vertebral notch Inf. vertebral notch Intervertebral foramen Cervical vertebrae: 7 Typical (C3-C6) Transverse foramen C1, Atlas C2, Axis: dens C7 Thoracic vertebrae: 12 Typical (T2-T10) T1 T11, 12 Lumbar vertebrae: 5 Typical (L1-4) Sacrum: 5 Ala Anterior sacral foramina Posterior sacral foramina Sacral canal ANA Lab: Bone 2 Sacral hiatus promontory median sacral crest intermediate crest lateral crest Coccyx Horns Transverse process Thoracic cages Ribs: 12 pairs Typical ribs (R3-R10): Head, 2 facets intermediate crest neck tubercle angle costal cartilage costal groove R1 R2 R11,12 Sternum Manubrium of sternum Clavicular notch for sternoclavicular joint body xiphoid process ANA Lab: Bone 3 Part II: Skull and Facial skeleton Skull Cranial skeleton, Calvaria (neurocranium) Facial skeleton (viscerocranium) Overview: identify the margin of each bone Cranial skeleton 1. Lateral view Frontal Temporal Parietal Occipital 2. Cranial base midline: Ethmoid, Sphenoid, Occipital bilateral: Temporal Viscerocranium 1. Anterior view Ethmoid, Vomer, Mandible Maxilla, Zygoma, Nasal, Lacrimal, Inferior nasal chonae, Palatine 2. Inferior view Palatine, Maxilla, Zygoma Sutures: external view vs. internal view Coronal suture Sagittal suture Lambdoid suture External appearance of skull Posterior view external occipital protuberance -

Morphometric Analysis of Sella Turcica and Its

International Journal of Dental and Health Sciences Original Article Volume 04,Issue 01 MORPHOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF SELLA TURCICA AND ITS CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE Priya Damodaran1, Yuvaraj.M2, Priyadarshini.A3, Sankaran.P.K4, Kalaiarasi.P5, Madhu Radhakrishnan6 1. Student, Compulsory Rotarory Residential Internship, Ragas dental college and hospital, Tamil nadu 2. Tutor, Department of Anatomy, Saveetha medical college and hospital, Thandalam, Tamil nadu 3. Tutor, Department of Anatomy, Saveetha medical college and hospital, Thandalam, Tamil nadu 4. Associate professor, Department of Anatomy, Saveetha medical college and hospital, Thandalam, Tamil nadu 5. Student, Compulsory Rotarory Residential Internship, Ragas dental college and hospital, Tamil nadu 6. Student, Compulsory Rotarory Residential Internship, Ragas dental college and hospital, Tamil nadu ABSTRACT: Sella turcica is an important and commonly used cranial landmark in many ventures. This work aims to measure and study sella turcica size and shape variations which is important for neurologists and neurosurgeons to avoid any damage to the sellar region and in identifying any pathological signs involving pituitary gland. The study was done with 102 dried human skulls where the gender of the skulls was not taken into consideration. The study was mainly concentrated to analyze the parameters of sella turcica. The average of sella turcica length, breadth and depth were calculated to be 10.59mm, 10.76mm and 9.23mm respectively. Most commonly found shape of sella turcica is normal (56.8%). These observations are essential in providing reference standard values. Keywords: Sella turcica, Sella size, Sella shape, Hypophyseal fossa INTRODUCTION The Sella turcica, a saddle shaped chiasma, inferiorly by sphenoid sinus, depression, is an important bony entity medially by cavernous sinus, oculomotor which is located in the body of the nerve, trochlear nerve, abducent nerve, sphenoid bone of the middle cranial ophthalmic nerve, maxillary nerve, fossa and is bounded by the two anterior internal carotid artery.