THE IMPACT of ELECTORAL RULE CHANGE on PARTY CAMPAIGN STRATEGY Hong Kong As a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03)

LC Paper No. CB(1)1017/17-18(03) 25th May 2018 Legislative Council Complex 1 Legislative Council Road Central, Hong Kong Dear Members of Legislative Council, Public Hearing on May 28th 2018: Review of relevant provisions under Cap. 586 We write to express our continued support for the Hong Kong Government's commitment to protecting and conserving wildlife, under the Protection of Endangered Species Ordinance (Cap. 586). We are grateful for the government’s recent amendments to Cap. 586, implementing the three-step plan to ban the Hong Kong ivory trade and the increase in maximum penalties under Cap 586. However, there remain challenges for the regulation of wildlife trade in Hong Kong and in tackling wildlife crime, which we suggest addressing through legalisation. The challenges, as we see them, include: The vast scale of the legal trade in shark fins: - In 2017, Hong Kong imported approximately 5,000 metric tonnes (MT) of shark fins1. - Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), species traded for the seafood and TCM industries, including shark fins, sea cucumber and seahorses, dominated wildlife imports by volume between 2007 to 2016 (87%). - This is all the more concerning, as a recent paper2 revealed that nearly one-third of the species currently identified within the trade in Hong Kong are considered ‘Threatened’ by the IUCN. An illegal trade in shark fins also thrives in Hong Kong: - Out of the 12 endangered shark species internationally protected under CITES regulations, five are known to have been seized as they were trafficked to Hong Kong over the last five years. -

Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 4, No.2: 155-175 Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality Ma Ngok Abstract Hong Kong is a paradox in democratization and modernization theory: it has a vibrant civil society and high level of economic development, but very slow democratization. Hong Kong’s status as a hybrid regime and its power dependence on China shape the dynamics of civil society in Hong Kong. The ideological orientations and organizational form of its civil society, and its detachment from the political society, prevent civil society in Hong Kong from engineering a formidable territory-wide movement to push for institutional reforms. The high level of civil liberties has reduced the sense of urgency, and the protracted transition has led to transition fatigue, making it difficult to sustain popular mobilization. Years of persistent civil society movements, however, have created a perennial legitimacy problem for the government, and drove Beijing to try to set a timetable for full democracy to solve the legitimacy and governance problems of Hong Kong. Key words: Civil society, democratization in Hong Kong, dual structure, hybrid regime, protracted transition, transition fatigue. For many a democratization theorist, the slow democratization of Hong Kong is anomalous. As one of the most advanced cities in the world, by as early as the 1980s, Hong Kong had passed the “zone of transition” postulated by the modernization theorists. Hong Kong also had a vibrant civil society, a sizeable middle class, many civil liberties that rivaled Western democracies, one of the freest presses in Asia, and independent courts. -

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS for GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5Pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday)

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS FOR GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday) Geographical Date of List (Surname First) Alias Gender Occupation Political Affiliation Remarks Constituency Nomination Hong Kong Island SIN Chung-kai M Politician The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 YEUNG Sum M The Honorary Assistant Professor The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHAI Man-hon M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHENG Lai-king F Registered Social Worker The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 LEUNG Suk-ching F District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 HUI Chi-fung M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island HUI Ching-on M Legal and Financial Consultant 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island IP LAU Suk-yee Regina F Chairperson/Board of Governors New People's Party 18/7/2012 WONG Chor-fung M Public Policy Researcher New People's Party 18/7/2012 TSE Tsz-kei M Community Development Officer New People's Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Kin-yee Miriam F Solicitor Liberal Party 18/7/2012 SHIU Ka-fai M Managing Director Liberal Party 18/7/2012 LEE Chun-keung Michael M Manager Liberal Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LO Wing-lok M Medical Practitioner 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Gar-hung Christopher M Retirement Benefits Consultant People Power 18/7/2012 SHIU Yeuk-yuen M Company Director 18/7/2012 AU YEUNG Ying-kit Jeff M Family Doctor 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island CHUNG Shu-kun Christopher Chris M Full-time District Councillor Democratic Alliance -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Introduction: the Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy

Notes Introduction: The Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy 1 . Charles Tilly, Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 7. 2 . Ibid . 3 . Ibid ., p. 9. 4 . Ibid . 5 . Ibid ., p. xi. 6 . Ibid . 7 . Ibid ., p. 13. 8 . Charles Tilly, Trust and Rule (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 12. 9 . Ibid. 10 . Ibid ., p. 104. 11 . Tilly, Democracy , p. 135. 12 . Ibid ., p. 136. 13 . Ibid ., p. 146. 14 . Ibid ., pp. 110–111. 15 . Ibid ., p. 110. 16 . Ibid ., p. 135. 17 . David Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” in David Potter, David Goldblatt, Margaret Kiloh and Paul Lewis, eds., Democratization (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 3–5. 18 . See, for example, Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (London: Heinemann, 1983). 19 . Ibid ., p. 21. 20 . Ibid . 21 . Ibid . 22 . Ibid ., p. 15. 23 . Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Transition from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). 24 . Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” p. 29. 25 . Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), p. 7. 26 . Ibid ., p. 38. 27 . Ibid ., pp. 65–66. 28 . Ibid ., p. 73. 29 . Ibid ., p. 86. 30 . Ibid ., pp. 93–94. 31 . Ibid ., p. 100. 32 . Ibid ., p. 122. 33 . Ibid ., p. 123. 34 . Ibid ., p. 142. 160 Notes 161 35 . Ibid ., p. 151. 36 . Ibid ., pp. 152–153. 37 . Ibid ., p. 159. 38 . Ibid ., p. 159. 39 . Ibid ., p. 171. 40 . Ibid ., p. 192. 41 . Ibid ., p. 199. 42 . Ibid ., p. 202. 43 . Ibid ., p. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA and FRAGMENTATION

Journal of East Asian Studies 17 (2017), 215–231 doi:10.1017/jea.2016.43 John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA AND FRAGMENTATION IN HONG KONG Abstract The directly elected representatives to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council are chosen by list propor- tional representation (PR) using the Hare Quota and Largest Remainders (HQLR) formula. This formula rewards political alliances of small to moderate size and discourages broader unions. Hong Kong’s political leaders have responded to those incentives by fragmenting their electoral alliances rather than expanding them. The level of list fragmentation observed in Hong Kong is not inherent to PR elections. Alternative PR formulas would generate incentives to form broader, more encompassing alliances. Indeed, most countries that use PR employ such formulas, and the most commonly used PR formula would generate incentives opposite to HQLR’s, reward- ing broader electoral alliances rather than divisions. Keywords Hong Kong, Legislative Council, elections, electoral system, proportional representation INTRODUCTION Hong Kong’s political agenda has featured intense debates and conflict in recent years over how its top officials are elected (Langer 2007; Zhang 2010;Ip2014; Young 2014). This article reviews how the rules for electing Hong Kong’s legislators have affected party system development and limited the effectiveness of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Building on existing scholarship on how votes are translated into LegCo representation, I examine how electoral rules shape the strategies pursued by Hong Kong party leaders. I also place Hong Kong elections in a broader comparative per- spective, illustrating how LegCo electoral outcomes would differ under the proportional representation formula most commonly used in democracies around the world. -

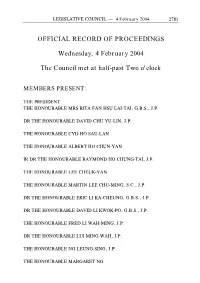

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 4

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 4 February 2004 2781 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 4 February 2004 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG 2782 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 4 February 2004 THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P.