John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA and FRAGMENTATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 4, No.2: 155-175 Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality Ma Ngok Abstract Hong Kong is a paradox in democratization and modernization theory: it has a vibrant civil society and high level of economic development, but very slow democratization. Hong Kong’s status as a hybrid regime and its power dependence on China shape the dynamics of civil society in Hong Kong. The ideological orientations and organizational form of its civil society, and its detachment from the political society, prevent civil society in Hong Kong from engineering a formidable territory-wide movement to push for institutional reforms. The high level of civil liberties has reduced the sense of urgency, and the protracted transition has led to transition fatigue, making it difficult to sustain popular mobilization. Years of persistent civil society movements, however, have created a perennial legitimacy problem for the government, and drove Beijing to try to set a timetable for full democracy to solve the legitimacy and governance problems of Hong Kong. Key words: Civil society, democratization in Hong Kong, dual structure, hybrid regime, protracted transition, transition fatigue. For many a democratization theorist, the slow democratization of Hong Kong is anomalous. As one of the most advanced cities in the world, by as early as the 1980s, Hong Kong had passed the “zone of transition” postulated by the modernization theorists. Hong Kong also had a vibrant civil society, a sizeable middle class, many civil liberties that rivaled Western democracies, one of the freest presses in Asia, and independent courts. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Introduction: the Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy

Notes Introduction: The Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy 1 . Charles Tilly, Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 7. 2 . Ibid . 3 . Ibid ., p. 9. 4 . Ibid . 5 . Ibid ., p. xi. 6 . Ibid . 7 . Ibid ., p. 13. 8 . Charles Tilly, Trust and Rule (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 12. 9 . Ibid. 10 . Ibid ., p. 104. 11 . Tilly, Democracy , p. 135. 12 . Ibid ., p. 136. 13 . Ibid ., p. 146. 14 . Ibid ., pp. 110–111. 15 . Ibid ., p. 110. 16 . Ibid ., p. 135. 17 . David Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” in David Potter, David Goldblatt, Margaret Kiloh and Paul Lewis, eds., Democratization (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 3–5. 18 . See, for example, Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (London: Heinemann, 1983). 19 . Ibid ., p. 21. 20 . Ibid . 21 . Ibid . 22 . Ibid ., p. 15. 23 . Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Transition from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). 24 . Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” p. 29. 25 . Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), p. 7. 26 . Ibid ., p. 38. 27 . Ibid ., pp. 65–66. 28 . Ibid ., p. 73. 29 . Ibid ., p. 86. 30 . Ibid ., pp. 93–94. 31 . Ibid ., p. 100. 32 . Ibid ., p. 122. 33 . Ibid ., p. 123. 34 . Ibid ., p. 142. 160 Notes 161 35 . Ibid ., p. 151. 36 . Ibid ., pp. 152–153. 37 . Ibid ., p. 159. 38 . Ibid ., p. 159. 39 . Ibid ., p. 171. 40 . Ibid ., p. 192. 41 . Ibid ., p. 199. 42 . Ibid ., p. 202. 43 . Ibid ., p. -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 10803 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 June 2016 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 10804 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S. -

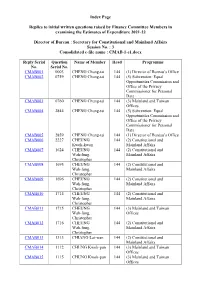

Administration's Replies to Members Initial Written Questions

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Director of Bureau : Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Session No. : 3 Consolidated e-file name : CMAB-1-e1.docx Reply Serial Question Name of Member Head Programme No. Serial No. CMAB001 0003 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (1) Director of Bureau’s Office CMAB002 0759 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (5) Subvention: Equal Opportunities Commission and Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data CMAB003 0760 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Offices CMAB004 2844 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (5) Subvention: Equal Opportunities Commission and Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data CMAB005 2859 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (1) Director of Bureau’s Office CMAB006 2227 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Kwok-kwan Mainland Affairs CMAB007 1624 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB008 1695 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB009 1696 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB010 1714 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB011 1715 CHEUNG 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Wah-fung, Offices Christopher CMAB012 1716 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB013 1313 CHIANG Lai-wan 144 (2) Constitutional and Mainland Affairs CMAB014 1112 CHUNG Kwok-pan 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Offices CMAB015 1115 CHUNG Kwok-pan 144 (3) Mainland -

United Front Organizations As a Political Machine Political Clientelism, Authoritarian Elections, and Electoral Breakthrough in Hong Kong

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 16, No. 2: 101-120 United Front Organizations as a Political Machine Political Clientelism, Authoritarian Elections, and Electoral Breakthrough in Hong Kong Eliza W. Y. Lee Abstract The political machine that supports political clientelism in Hong Kong is adapted from united front organizations, which are the party-state’s institutional infrastructure for exercising indirect rule over Hong Kong. As machinery intended for penetrating society and building social alliances in support of the party-state, it is readily adaptable for the purpose of building clientelistic networks for electoral purposes. The necessary and massive human, financial, and organizational resources, in short, the penetrative capacity of united front organizations, compensate for the weak dependency of voters on patronage goods and the limited availability of state resources for political patronage. The electoral breakthrough in the 2019 District Council elections revealed the limitations of weak dependency and, hence, the unviability of the political machine. Keywords: Authoritarian elections, electoral breakthrough, Hong Kong, political clientelism, united front organizations. In Hong Kong, political clientelism in elections has been on the rise in the past decade. Ridiculed as shezhaibingzong (the Chinese acronym for snake soup, vegetarian banquet, Mid-Autumn Festival mooncake, and Dragon Boat Festival dumpling) by its critics, material favors are regularly offered by politicians to residents in the community, from food, gift packs, group tours, banquets, stationery packages for students, basic health care (such as free blood pressure checks for the elderly or consultations for traditional Chinese medicine), to household services, and more. Such favors are widely extended by pro-Beijing political parties, and the general perception is that they have become an Eliza W. -

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China's December 2007

Order Code RS22787 January 10, 2008 Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China’s December 2007 Decision Michael F. Martin Analyst in Asian Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Summary The prospects for democratization in Hong Kong became clearer following a decision of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress (NPCSC) on December 29, 2007. The NPCSC’s decision effectively set the year 2017 as the earliest date for the direct election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the year 2020 as the earliest date for the direct election of all members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (Legco). However, ambiguities in the language used by the NPCSC have contributed to differences in interpretation of its decision. According to Hong Kong’s current Chief Executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the decision sets a clear timetable for democracy in Hong Kong. However, representatives of Hong Kong’s “pro- democracy” parties believe the decision includes no solid commitment to democratization in Hong Kong. The NPCSC’s decision also established some guidelines for the process of election reform in Hong Kong, including what can and cannot be altered in the 2012 elections. Since China established the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) on July 1, 1997, there have been questions about when and how the democratization of Hong Kong will take place.1 At present, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is selected by an “Election Committee” of 800 largely appointed people, and its Legislative Council (Legco) consists of 30 members elected by universal suffrage in five geographic districts and 30 members selected by 28 “functional constituencies” representing various important sectors. -

Hong Kong's Democratization and China's Obligations Under Public International Law Alvin Y.H

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 40 | Issue 2 Article 3 2015 Road to Nowhere: Hong Kong's Democratization and China's Obligations Under Public International Law Alvin Y.H. Cheung Follow this and additional works at: http://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Alvin Y. Cheung, Road to Nowhere: Hong Kong's Democratization and China's Obligations Under Public International Law, 40 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2014). Available at: http://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol40/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROAD TO NOWHERE: HONG KONG’S DEMOCRATIZATION AND CHINA’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW Alvin Y.H. Cheung* INTRODUCTION:WE’RE NOT LITTLE CHILDREN ................467 I. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY ..........................................475 A. The United Kingdom’s Acquisition of Hong Kong ..475 B. Background to the Joint Declaration......................476 C. The Drafting of the Basic Law ................................478 D. 1990-1997: A Day Late and a Dollar Short............479 E. 2003-2004: Beijing Usurps Initiative......................481 F. 2007: Jam Tomorrow...............................................484 G. 2009-2010: Divide and Conquer .............................485 H. 2012: Playing Charades ..........................................487 I. The Current Debate...................................................488 1. 2013: The Moderates Lose Patience.....................489 2. 2014: Beijing’s Gloves Come Off; Hong Kong’s Umbrellas Come Out ................................................494 3. Who Gets to Nominate? ........................................498 II. APPLICABLE LAW..........................................................504 * Visiting Scholar, U.S.-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law; of the Hong Kong Bar, barrister (non-practicing). -

Comparative Analysis of Hong Kong and Taiwan's Independence Movements: a Case Study of Identity and Politics Using Social Movement Theory

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2017 Comparative Analysis of Hong Kong and Taiwan's Independence Movements: a case study of identity and politics using social movement theory Sarah A. Hasselle University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hasselle, Sarah A., "Comparative Analysis of Hong Kong and Taiwan's Independence Movements: a case study of identity and politics using social movement theory" (2017). Honors Theses. 827. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/827 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Analysis of Hong Kong and Taiwan’s Independence Movements: a case study of identity and politics using social movement theory By Sarah A. Hasselle A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi Oxford, Mississippi May 2017 Approved: ____________________________ Advisor Dr. Noell Wilson ____________________________ Reader: Dr. William Schneck ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Gang Guo © 2017 Sarah Anne Hasselle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Acknowledgements I first wish to acknowledge my thesis mentor, Doctor Noell Wilson, for her guidance in helping me write my thesis. She not only provided support for me during the writing and editing process, but she has also been helpful to me for deciding my next steps in life. -

Consultation Paper Access to Information

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG ACCESS TO INFORMATION SUB-COMMITTEE CONSULTATION PAPER ACCESS TO INFORMATION This consultation paper can be found on the Internet at: <http://www.hkreform.gov.hk> December 2018 This Consultation Paper has been prepared by the Access to Information Sub-committee of the Law Reform Commission. It does not represent the final views of either the Sub-committee or the Law Reform Commission, and is circulated for comment and discussion only. The Sub-committee would be grateful for comments on this Consultation Paper by 5 March 2019. All correspondence should be addressed to: The Secretary Access to Information Sub-committee The Law Reform Commission 4th Floor, East Wing, Justice Place 18 Lower Albert Road Central Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 3918 4097 Fax: (852) 3918 4096 E-mail: [email protected] It may be helpful for the Commission and the Sub-committee, either in discussion with others or in any subsequent report, to be able to refer to and attribute comments submitted in response to this Consultation Paper. Any request to treat all or part of a response in confidence will, of course, be respected, but if no such request is made, the Commission will assume that the response is not intended to be confidential. It is the Commission's usual practice to acknowledge by name in the final report anyone who responds to a consultation paper. If you do not wish such an acknowledgment, please say so in your response. THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG ACCESS TO INFORMATION SUB-COMMITTEE CONSULTATION PAPER ACCESS TO INFORMATION ______________________ CONTENTS Chapter Page Preface Terms of Reference 1 The Sub-committee 1 Meetings 2 The link with Archives Law 2 Overview of Access to Information in Hong Kong 3 Statistics on Access to Information Requests 3 Methodology adopted for the consultation exercise 4 1.