Consultation Paper Access to Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (C

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (c. 51)i, ii An Act to make new provision with respect to public records and the Public Record Office, and for connected purposes. [23rd July 1958] General responsibility of the Lord Chancellor for public records. 1. - (1) The direction of the Public Record Office shall be transferred from the Master of the Rolls to the Lord Chancellor, and the Lord Chancellor shall be generally responsible for the execution of this Act and shall supervise the care and preservation of public records. (2) There shall be an Advisory Council on Public Records to advise the Lord Chancellor on matters concerning public records in general and, in particular, on those aspects of the work of the Public Record Office which affect members of the public who make use of the facilities provided by the Public Record Office. The Master of the Rolls shall be chairman of the said Council and the remaining members of the Council shall be appointed by the Lord Chancellor on such terms as he may specify. [(2A) The matters on which the Advisory Council on Public Records may advise the Lord Chancellor include matters relating to the application of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 to information contained in public records which are historical records within the meaning of Part VI of that Act.iii] (3) The Lord Chancellor shall in every year lay before both Houses of Parliament a report on the work of the Public Record Office, which shall include any report made to him by the Advisory Council on Public Records. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Access to Court Records – Terms of Reference

ACCESS TO COURT RECORDS – TERMS OF REFERENCE The Commission will review the existing rules governing access to Court records and make proposals for any changes that are necessary and desirable. In particular the Commission is asked to consider: 1 What documentation held by a court or tribunal (hard copy and other) should form part of the court record and in particular what administrative documents are included. 2 What should be the principles and rules upon which access to court records, can be granted or withheld and specifically: (a) What is the relationship between these principles and rules and those underpinning the Official Information Act 1982, the Archives Act 1957 and the Privacy Act 1993 (b) How does the format of the court record, whether it be hard copy or electronic or other, affect any of these principles or require additional considerations? (c) Should there be special rules when requests for access are: (i) by accredited news media; or (ii) for research and statistical purposes (d) Should there be a single access code across and within all court and tribunal jurisdictions or specific codes (e) What are the principles upon which fees for accessing court and Tribunal records should be fixed? C:\Documents and Settings\TMcGlennon\Desktop\Consultation draft post peer review.doc 29/03/2006 12:22 1 3 What should be the principles and rules governing disclosure of documentation held by a Court or Tribunal which is not part of a court record? 4 What should be the principles and rules under which court staff operates when handling access requests. -

Privacy, Openness and Archives in the Public Domain

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Silvanus, Genevieve (2018) Privacy, openness and archives in the public domain. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/39779/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Privacy, openness and archives in the public domain Genevieve Laura Silvanus PhD 2018 Privacy, openness and archives in the public domain Genevieve Laura Silvanus A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Engineering & Environment October 2018 Abstract This research investigates the issues surrounding access to archives at non-national archives in England with a multi-stakeholder perspective. Using a combination of focus groups with non-managerial archivists, academic researchers, non-professional family and local historians and a series of semi-structured interviews with leading experts, it attempts to show the issues in the “real world” rather than an idealised one. -

Vellum: Printing Record Copies of Public Acts

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07451, 15 August 2018 Vellum: printing record By Richard Kelly copies of public Acts Inside: 1. Printing record copies of public Acts 2. Establishing the practice of printing on vellum 3. Proposals to change the practice 4. Decision to change practice 5. Further information www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07451, 15 August 2018 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Printing record copies of public Acts 5 1.1 The Parliamentary Archives 5 2. Establishing the practice of printing on vellum 6 2.1 First Report of the Select Committee on Printing 6 Ingrossment and inrolment 6 Alternatives 7 2.2 Resolution of the House of Lords and the report of the Clerk Assistant 9 2.3 House of Lords resolutions 9 2.4 House of Commons amendments 10 2.5 Final ingrossments and first prints 10 Public Acts 10 Private Acts 11 3. Proposals to change the practice 12 3.1 1999 debates and history 12 3.2 House of Commons Administration Committee report 2015-16 13 3.3 Parliamentary Questions 13 3.4 Another Commons debate on vellum 15 3.5 Cabinet Office intervention 16 3.6 Commons debate on Record Copies of Acts, 20 April 2016 17 4. Decision to change practice 20 4.1 Lords response to Commons Vote 20 4.2 House of Commons Commission response 20 4.3 Final Act to be printed on vellum 20 5. Further information 21 5.1 Historic Hansard 21 5.2 Freedom of Information requests 21 Cover page image copyright: Abolition of Slave Trade 1807 by UK Parliament 3 Vellum: printing record copies of public Acts Summary Record copies of public Acts, passed since the beginning of the 2015 Parliament, have been printed on archival paper, with front and back vellum covers. -

Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 4, No.2: 155-175 Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality Ma Ngok Abstract Hong Kong is a paradox in democratization and modernization theory: it has a vibrant civil society and high level of economic development, but very slow democratization. Hong Kong’s status as a hybrid regime and its power dependence on China shape the dynamics of civil society in Hong Kong. The ideological orientations and organizational form of its civil society, and its detachment from the political society, prevent civil society in Hong Kong from engineering a formidable territory-wide movement to push for institutional reforms. The high level of civil liberties has reduced the sense of urgency, and the protracted transition has led to transition fatigue, making it difficult to sustain popular mobilization. Years of persistent civil society movements, however, have created a perennial legitimacy problem for the government, and drove Beijing to try to set a timetable for full democracy to solve the legitimacy and governance problems of Hong Kong. Key words: Civil society, democratization in Hong Kong, dual structure, hybrid regime, protracted transition, transition fatigue. For many a democratization theorist, the slow democratization of Hong Kong is anomalous. As one of the most advanced cities in the world, by as early as the 1980s, Hong Kong had passed the “zone of transition” postulated by the modernization theorists. Hong Kong also had a vibrant civil society, a sizeable middle class, many civil liberties that rivaled Western democracies, one of the freest presses in Asia, and independent courts. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Introduction: the Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy

Notes Introduction: The Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy 1 . Charles Tilly, Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 7. 2 . Ibid . 3 . Ibid ., p. 9. 4 . Ibid . 5 . Ibid ., p. xi. 6 . Ibid . 7 . Ibid ., p. 13. 8 . Charles Tilly, Trust and Rule (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 12. 9 . Ibid. 10 . Ibid ., p. 104. 11 . Tilly, Democracy , p. 135. 12 . Ibid ., p. 136. 13 . Ibid ., p. 146. 14 . Ibid ., pp. 110–111. 15 . Ibid ., p. 110. 16 . Ibid ., p. 135. 17 . David Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” in David Potter, David Goldblatt, Margaret Kiloh and Paul Lewis, eds., Democratization (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 3–5. 18 . See, for example, Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (London: Heinemann, 1983). 19 . Ibid ., p. 21. 20 . Ibid . 21 . Ibid . 22 . Ibid ., p. 15. 23 . Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Transition from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). 24 . Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” p. 29. 25 . Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), p. 7. 26 . Ibid ., p. 38. 27 . Ibid ., pp. 65–66. 28 . Ibid ., p. 73. 29 . Ibid ., p. 86. 30 . Ibid ., pp. 93–94. 31 . Ibid ., p. 100. 32 . Ibid ., p. 122. 33 . Ibid ., p. 123. 34 . Ibid ., p. 142. 160 Notes 161 35 . Ibid ., p. 151. 36 . Ibid ., pp. 152–153. 37 . Ibid ., p. 159. 38 . Ibid ., p. 159. 39 . Ibid ., p. 171. 40 . Ibid ., p. 192. 41 . Ibid ., p. 199. 42 . Ibid ., p. 202. 43 . Ibid ., p. -

John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA and FRAGMENTATION

Journal of East Asian Studies 17 (2017), 215–231 doi:10.1017/jea.2016.43 John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA AND FRAGMENTATION IN HONG KONG Abstract The directly elected representatives to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council are chosen by list propor- tional representation (PR) using the Hare Quota and Largest Remainders (HQLR) formula. This formula rewards political alliances of small to moderate size and discourages broader unions. Hong Kong’s political leaders have responded to those incentives by fragmenting their electoral alliances rather than expanding them. The level of list fragmentation observed in Hong Kong is not inherent to PR elections. Alternative PR formulas would generate incentives to form broader, more encompassing alliances. Indeed, most countries that use PR employ such formulas, and the most commonly used PR formula would generate incentives opposite to HQLR’s, reward- ing broader electoral alliances rather than divisions. Keywords Hong Kong, Legislative Council, elections, electoral system, proportional representation INTRODUCTION Hong Kong’s political agenda has featured intense debates and conflict in recent years over how its top officials are elected (Langer 2007; Zhang 2010;Ip2014; Young 2014). This article reviews how the rules for electing Hong Kong’s legislators have affected party system development and limited the effectiveness of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Building on existing scholarship on how votes are translated into LegCo representation, I examine how electoral rules shape the strategies pursued by Hong Kong party leaders. I also place Hong Kong elections in a broader comparative per- spective, illustrating how LegCo electoral outcomes would differ under the proportional representation formula most commonly used in democracies around the world. -

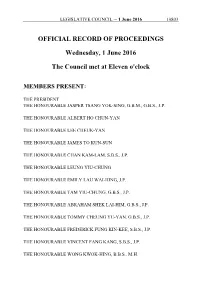

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 10803 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 June 2016 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 10804 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S. -

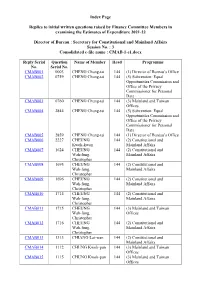

Administration's Replies to Members Initial Written Questions

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2021-22 Director of Bureau : Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Session No. : 3 Consolidated e-file name : CMAB-1-e1.docx Reply Serial Question Name of Member Head Programme No. Serial No. CMAB001 0003 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (1) Director of Bureau’s Office CMAB002 0759 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (5) Subvention: Equal Opportunities Commission and Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data CMAB003 0760 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Offices CMAB004 2844 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (5) Subvention: Equal Opportunities Commission and Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data CMAB005 2859 CHENG Chung-tai 144 (1) Director of Bureau’s Office CMAB006 2227 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Kwok-kwan Mainland Affairs CMAB007 1624 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB008 1695 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB009 1696 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB010 1714 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB011 1715 CHEUNG 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Wah-fung, Offices Christopher CMAB012 1716 CHEUNG 144 (2) Constitutional and Wah-fung, Mainland Affairs Christopher CMAB013 1313 CHIANG Lai-wan 144 (2) Constitutional and Mainland Affairs CMAB014 1112 CHUNG Kwok-pan 144 (3) Mainland and Taiwan Offices CMAB015 1115 CHUNG Kwok-pan 144 (3) Mainland