Civil Society and Democratization in Hong Kong Paradox and Duality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal

Hong Kong Walkability Analysis IQP Project Proposal Sponsoring Agencies: Designing Hong Kong and Harbour Business Forum Submitted to: Project Advisor: Zhikun Hou, WPI Professor Project Co‐advisor: Robert Kinicki, WPI Professor On‐Site Liaison: Paul Zimmerman, Designing Hong Kong On‐Site Co‐Liaison: Dr. Sujata S. Govada, Harbour Business Forum Submitted by: Michael Audi Kathryn Byorkman Alison Couture Suzanne Najem Date Submitted: 15 December 2010 Creighton Peet ID 2050 Instructor Table of Contents Title Page .............................................................................................................................................. i Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. ii Table of Figures .................................................................................................................................. iv Table of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ vi 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Background .................................................................................................................................... 4 -

In Hong Kong the Political Economy of the Asia Pacific

The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez- Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific Series editor Vinod K. Aggarwal More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7840 Fujio Mizuoka Contrived Laissez-Faireism The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong Fujio Mizuoka Professor Emeritus Hitotsubashi University Kunitachi, Tokyo, Japan ISSN 1866-6507 ISSN 1866-6515 (electronic) The Political Economy of the Asia Pacific ISBN 978-3-319-69792-5 ISBN 978-3-319-69793-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69793-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017956132 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Strategies for Optimizing Hong Kong's Living Environment Beyond 2030

SHAPING HONG KONG: STRATEGIES FOR OPTIMIZING HONG KONG’S LIVING ENVIRONMENT BEYOND 2030 PRINCIPLES, DIRECTIONS, PARAMETERS AND STRATEGY Research Team: Mee Kam NG Yee LEUNG Ka Ling CHEUNG Kam Yee YIP Institute of Future Cities The Chinese University of Hong Kong SHAPING HONG KONG: STRATEGIES FOR OPTIMIZING HONG KONG’S LIVING ENVIRONMENT BEYOND 2030 PRINCIPLES, DIRECTIONS, PARAMETERS AND STRATEGY September 2015 Shaping Hong Kong—Strategies for optimising Hong Kong’s living environment beyond 2030 PRINCIPLES, DIRECTIONS, PARAMETERS & STRATEGY OF LOW-CARBON INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT Table of Contents Page Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Research Methodology 5 3. The Need to Move Beyond 2030 6 4. Guiding Principles for Low-Carbon Infrastructure Development 13 5. Overall Parameters of Low-Carbon Infrastructure Development in Hong 19 Kong beyond 2030 6. Low-Carbon Infrastructure Development Strategy: City-level Priorities 23 7. Low-Carbon Infrastructure Development Strategy: Sector-level Priorities 29 8. Possible Infrastructure Investment Priorities 51 9. Conclusion 52 References 55 List of Figures 1. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Hong Kong from 1990 -2012 10 2 Greenhouse Gas Emission Trends of Hong Kong by Sector from 1990-2012 11 3 Five Tracks of Low Carbon Green Growth 13 4 Key Areas of Concern of Civil Engineers 18 5 Integrated and Holistic Considerations of Infrastructure Systems 23 6 Smart Grid 41 7 Hong Kong Energy Consumption by Sector 41 8 Waste Management Structure in Hong Kong and other Asian Areas 46 9 Towards Low-Carbon -

CHAPTER 8 Radio Television Hong Kong RTHK

CHAPTER 8 Radio Television Hong Kong RTHK: governance and strategic management Audit Commission Hong Kong 31 March 2006 This audit review was carried out under a set of guidelines tabled in the Provisional Legislative Council by the Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee on 11 February 1998. The guidelines were agreed between the Public Accounts Committee and the Director of Audit and accepted by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report No. 46 of the Director of Audit contains 9 Chapters which are available on our website at http://www.aud.gov.hk. Audit Commission 26th floor, Immigration Tower 7 Gloucester Road Wan Chai Hong Kong Tel : (852) 2829 4210 Fax : (852) 2824 2087 E-mail : [email protected] RTHK: GOVERNANCE AND STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT Contents Paragraph PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.2 – 1.8 Recent reviews of RTHK’s systems and procedures 1.9 Value for money audit of RTHK 1.10 Audit review of governance and strategic management 1.11 General response from the Administration 1.12 Acknowledgement 1.13 PART 2: COMPLIANCE CULTURE AND INTERNAL CONTROL 2.1 Management responsibility for the 2.2 – 2.3 prevention and detection of irregularities Observations on non-compliance in RTHK 2.4 – 2.10 Audit observations 2.11 – 2.13 Need to enhance internal control 2.14 Audit observations 2.15 – 2.21 Audit recommendations 2.22 Response from the Administration 2.23 Need to foster a compliance culture 2.24 Audit observations 2.25 Audit recommendations 2.26 Response from the Administration 2.27 – 2.28 — i — Paragraph -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Introduction: the Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy

Notes Introduction: The Uniqueness of Hong Kong Democracy 1 . Charles Tilly, Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 7. 2 . Ibid . 3 . Ibid ., p. 9. 4 . Ibid . 5 . Ibid ., p. xi. 6 . Ibid . 7 . Ibid ., p. 13. 8 . Charles Tilly, Trust and Rule (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 12. 9 . Ibid. 10 . Ibid ., p. 104. 11 . Tilly, Democracy , p. 135. 12 . Ibid ., p. 136. 13 . Ibid ., p. 146. 14 . Ibid ., pp. 110–111. 15 . Ibid ., p. 110. 16 . Ibid ., p. 135. 17 . David Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” in David Potter, David Goldblatt, Margaret Kiloh and Paul Lewis, eds., Democratization (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 3–5. 18 . See, for example, Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (London: Heinemann, 1983). 19 . Ibid ., p. 21. 20 . Ibid . 21 . Ibid . 22 . Ibid ., p. 15. 23 . Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter, Transition from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986). 24 . Potter, “Explaining Democratization,” p. 29. 25 . Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), p. 7. 26 . Ibid ., p. 38. 27 . Ibid ., pp. 65–66. 28 . Ibid ., p. 73. 29 . Ibid ., p. 86. 30 . Ibid ., pp. 93–94. 31 . Ibid ., p. 100. 32 . Ibid ., p. 122. 33 . Ibid ., p. 123. 34 . Ibid ., p. 142. 160 Notes 161 35 . Ibid ., p. 151. 36 . Ibid ., pp. 152–153. 37 . Ibid ., p. 159. 38 . Ibid ., p. 159. 39 . Ibid ., p. 171. 40 . Ibid ., p. 192. 41 . Ibid ., p. 199. 42 . Ibid ., p. 202. 43 . Ibid ., p. -

Level 3 Geography (91429) 2013

91429R 3 Level 3 Geography, 2013 91429 Demonstrate understanding of a given environment(s) through selection and application of geographic concepts and skills 9.30 am Friday 22 November 2013 Credits: Four RESOURCE BOOKLET Refer to this booklet to answer the questions for Geography 91429. Check that this booklet has pages 2 – 12 in the correct order and that none of these pages is blank. YOU MAY KEEP THIS BOOKLET AT THE END OF THE EXAMINATION. © New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the prior permission of the New Zealand QualificationsAuthority. 2 THE NATURAL AND CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT OF HONG KONG Resource A: Hong Kong’s Location and Territories Hong Kong is located on China’s south coast. It is surrounded by the South China Sea on the east, south, and west. Hong Kong primarily consists of three main territories: Hong Kong Island, Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories. Hong Kong was a British colony from 1842 until 1997, when China resumed sovereignty. For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. Figure 1: Location map For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. Figure 2: Key territories 3 Resource B: Average Annual Rainfall Distribution in Hong Kong (1981–2010) For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. Resource C: Average Annual Climate Data for Hong Kong For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. 4 Resource D: Satellite Image of Hong Kong For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. Resource E: Relief of Hong Kong For copyright reasons, this resource cannot be reproduced here. -

John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA and FRAGMENTATION

Journal of East Asian Studies 17 (2017), 215–231 doi:10.1017/jea.2016.43 John M. Carey ELECTORAL FORMULA AND FRAGMENTATION IN HONG KONG Abstract The directly elected representatives to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council are chosen by list propor- tional representation (PR) using the Hare Quota and Largest Remainders (HQLR) formula. This formula rewards political alliances of small to moderate size and discourages broader unions. Hong Kong’s political leaders have responded to those incentives by fragmenting their electoral alliances rather than expanding them. The level of list fragmentation observed in Hong Kong is not inherent to PR elections. Alternative PR formulas would generate incentives to form broader, more encompassing alliances. Indeed, most countries that use PR employ such formulas, and the most commonly used PR formula would generate incentives opposite to HQLR’s, reward- ing broader electoral alliances rather than divisions. Keywords Hong Kong, Legislative Council, elections, electoral system, proportional representation INTRODUCTION Hong Kong’s political agenda has featured intense debates and conflict in recent years over how its top officials are elected (Langer 2007; Zhang 2010;Ip2014; Young 2014). This article reviews how the rules for electing Hong Kong’s legislators have affected party system development and limited the effectiveness of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Building on existing scholarship on how votes are translated into LegCo representation, I examine how electoral rules shape the strategies pursued by Hong Kong party leaders. I also place Hong Kong elections in a broader comparative per- spective, illustrating how LegCo electoral outcomes would differ under the proportional representation formula most commonly used in democracies around the world. -

Cb(4)793/12-13(02)

LC Paper No. CB(4)793/12-13(02) Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting Extract from minutes of the meeting held on 11 March 2013 * * * * * Action IV. Radio Television Hong Kong's Community Involvement Broadcasting Service and the role and future of Radio Television Hong Kong (LC Paper No. CB(4)458/12-13(05) -- Administration's paper on Radio Television Hong Kong's Community Involvement Broadcasting Service and the role and future of Radio Television Hong Kong LC Paper No. CB(4)458/12-13(06) -- Paper on the role and future of Radio Television Hong Kong and issues relating to Community Involvement in Broadcasting prepared by the Legislative Council Secretariat (background brief) Presentation by the Administration At the invitation of the Chairman, Permanent Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (Communications and Technology) ("PSCED(CT)") briefed members on the progress of the roll out of the Community Involvement Broadcasting Service ("CIBS") and the role and future of Radio Television Hong Kong ("RTHK"). Details of the briefing were set out in the Administration's paper (LC Paper No. CB(4)458/12-13(05)). Action - 2 - Discussion Digital Audio Broadcasting and Community Involvement Broadcasting Services 2. Mr WONG Ting-kwong expressed concern about the low take-up rate of RTHK's five Digital Audio Broadcasting ("DAB") channels, which were formally launched on 17 September 2012. He also enquired about the measures taken by the Administration to enhance public interest in purchasing digital radios for DAB services. In response, the Director of Broadcasting ("D of B") said that the RTHK, together with other DAB operators, would add more fill-in stations to improve the transmission of DAB signals, and enhance its publicity effort and promotion strategies to tie in with the progress of the network rollout and take-up rate of the DAB services. -

Official Record of Proceedings

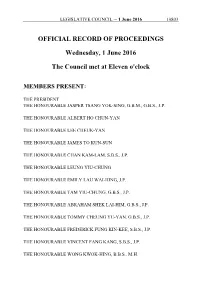

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 10803 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 June 2016 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 10804 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S.