Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

Equality As a Human Right: the Development of Anti-Discrimination Law in Hong Kong

Equality as a Human Right: The Development of Anti-Discrimination Law in Hong Kong CAROLE J. PETERSEN* The women's movement in Hong Kong has significantly benefited from the political and legal changes that oc- curred during the transition to 1997. Citizens of Hong Kong developed a greater awareness of human rights issues, and women have successfully identified equality as a "human right" deserving legalprotection. The women's movement has also allied itself with the increasingly democratic and assertiveLegislative Council. As a result, the legalprohibition offemale inheritance of land in Hong Kong was repealed in 1994 and the first law prohibiting sex discrimination was enacted in 1995. Additionally, Hong Kong's first Equal Opportunities Commission is being established. Ironically, the very developments that strengthened the women's movement in recent years-its association with the broaderhuman rights movement and with assertive legislators--may threaten it when China regains sovereignty. * Lecturer in Law, School of Professional and Continuing Education, University of Hong Kong. B.A., University of Chicago, 1981; J.D. Harvard Law School, 1984; Postgraduate Dip. Law of the PRC, University of Hong Kong, 1994. This article is a revised and updated version of a paper delivered at the 1995 Wolfgang Friedmann Confer- ence-Hong Kong: Financial Center of Asia, at Columbia Law School on March 30, 1995. From September 1993 to August 1995, the author served as a part-time consultant to Legislative Councillor Anna Wu and assisted her in the drafting of the Equal Opportunities Bill, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission Bill, and amendments to the Sex Discrimination Bill (described in Part V below). -

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Official Record of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 1117 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 30 November 1994 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL LEUNG MAN-KIN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. 1118 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. -

The 2012 Election Reforms

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2012 Election Reforms (name redacted) Specialist in Asian Affairs February 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R40992 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: The 2012 Election Reforms Summary Support for the democratization of Hong Kong has been an element of U.S. foreign policy for over 17 years. The Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-383) states, “Support for democratization is a fundamental principle of United States foreign policy. As such, it naturally applies to United States policy toward Hong Kong. This will remain equally true after June 30, 1997” (the date of Hong Kong’s reversion to China). The Omnibus Appropriations Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-8) provides at least $17 million for “the promotion of democracy in the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan …” The democratization of Hong Kong is also enshrined in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s quasi- constitution that was passed by China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) prior to China’s resumption of sovereignty over the ex-British colony on July 1, 1997. The Basic Law stipulates that the “ultimate aim” is the selection of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the members of its Legislative Council (Legco) by “universal suffrage.” However, it does not designate a specific date by which this goal is to be achieved. On November 18, 2009, Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen released the long- awaited “consultation document” on possible reforms for the city’s elections to be held in 2012. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

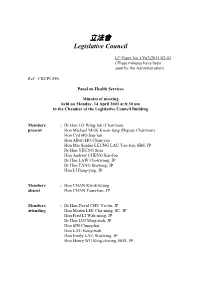

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)2011/02-03 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HS Panel on Health Services Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 14 April 2003 at 8:30 am in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Dr Hon LO Wing-lok (Chairman) present Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Mrs Sophie LEUNG LAU Yau-fun, SBS, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Dr Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon LI Fung-ying, JP Members : Hon CHAN Kwok-keung absent Hon CHAN Yuen-han, JP Members : Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP attending Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, JP Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Mr Thomas YIU, JP attending Deputy Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Mr Nicholas CHAN Assistant Secretary for Health, Welfare and Food Dr P Y LAM, JP Deputy Director of Health Dr W M KO, JP Director (Professional Services & Public Affairs) Hospital Authority Dr Thomas TSANG Consultant Clerk in : Ms Doris CHAN attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2) 4 Staff in : Ms Joanne MAK attendance Senior Assistant Secretary (2) 2 I. Confirmation of minutes (LC Paper No. CB(2)1735/02-03) The minutes of the regular meeting on 10 March 2003 were confirmed. -

On the Election of the Chief Executive in Hong Kong

- 1 - Viktor Ungemach: On the Election of the Chief Executive in Hong Kong. Head of Government or Lieutenant of Beijing? The election of the Chief Executive held in Hong Kong on March 25, 2007 was the third to take place since the crown colony was returned to the People's Republic of China and transformed into a so-called special administrative region (SAR). Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the former head of government, emerged victorious with 649 of 796 votes, whereas Alan Leong Kah-kit, his challenger from the pro-democratic camp, obtained only 123 votes. Although his programme hardly differed from that of his opponent, Mr Tsang was favoured from the start in the elections, which were accompanied by a public campaign for the first time. Their opinions differed only on the question of introducing universal suffrage, which was strongly advocated by Mr Leong. Properly speaking, the basic law of Hong Kong provides for the election of the Chief Executive to take place in 2007 and that of the Legislative Council in 2008. However, the realisation of these two projects was later predicated on current developments within the SAR, leaving Beijing sufficient scope for influencing Hong Kong politics. When the People's Republic of China said that Hong Kong's population lacked experience in dealing with democracy, it prompted discontent among that population, causing a record number of 500,000 people in the SAR to take to the streets in 2004 and, moreover, initiating the formation of several political parties that demand democracy. However, as their only common denominator was the call for a swift realisation of universal suffrage, the clout of the pro-democratic camp remained weak. -

Hong Kong Watch * * * * * * * International Parliamentarians

Hong Kong Watch * * * * * * * International parliamentarians condemn today’s imprisonment of the ‘most moderate and distinguished’ pro-democracy activists Today, authorities in Hong Kong have sentenced nine prominent pro-democracy activists for taking part in a peaceful protest in August 2019, including the the ‘father of Hong Kong’s democracy’ Martin Lee, ‘the owner of Apple Daily Jimmy Lai, and international barrister Margaret Ng. The nine pro-democracy activists which span the generations have received jail sentences and suspended sentences, with Jimmy Lai receiving 12 months, Lee Cheuk-yan receiving 12 months, Leung Kwok-hung receiving 18 months, Au Nok-hin receiving 10 months, and Cyd Ho receiving 8 months in prison and Margaret Ng receiving 12 month suspended sentence, Martin Lee receiving 11 months suspended sentence, Albert Ho receiving 12 months suspended sentence, and Leung Yiu-chung receiving an 8 month suspended sentence for the charge of ‘unlawful assembly’. U.N. Special Rapporteurs for human rights have previously called for the Hong Kong Government to withdraw the Public Order Ordinance which allows authorities to criminalise peaceful protest describing it as an assault on freedom of expression and freedom of assembly. A group of international parliamentarians led by Hong Kong Watch’s patron and the last British governor of Hong Kong, Lord Patten, have responded to the sentencing of the prominent pro-democracy activists. Their comments follow calls from over 100 UK MPs for the sanctioning of Hong Kong officials. U.K. Lord Patten of Barnes said: “The CCP's comprehensive assault on the freedoms of Hong Kong and its rule of law continues relentlessly. -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

立法會 Legislative Council

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2) 705/00-01 Ref : CB2/PL/FE LegCo Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene Minutes of Meeting held on Friday, 5 January 2001 at 9:30 am in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP (Chairman) Present Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon David CHU Yu-lin Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon CHAN Yuen-han Hon SIN Chung-kai Hon WONG Yung-kan Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, JP Dr Hon YEUNG Sum Hon YEUNG Yiu-chung Hon LAU Kong-wah Hon SZETO Wah Hon LAW Chi-kwong, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Michael MAK Kwok-fung Dr Hon LO Wing-lok Hon WONG Sing-chi Hon IP Kwok-him, JP Member : Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Absent Clerk in : Mrs Constance LI Attendance Chief Assistant Secretary (2)5 Staff in : Mrs Justina LAM - 2 - Attendance Assistant Secretary General 2 Miss Betty MA Senior Assistant Secretary (2)1 Ms Joanne MAK Senior Assistant Secretary (2)2 Action I. Election of Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the Panel for the 2000 - 2001 session Election of Chairman 1. Mr David CHU, Member of the highest precedence among those who had joined the Panel, presided over the election of Chairman of the Panel. Mr CHU called for nominations for the chairmanship of the Panel, in accordance with the election procedures set out in rule 20 and Appendix IV of the House Rules. 2.