Migration Control and Access to Welfare; the Precarious Inclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

29414 St Nr 32 Møte 73-74

2013 24. april – Muntlig spørretime 3123 Møte onsdag den 24. april 2013 kl. 10 Solveig Horne (FrP) [10:03:32]: På vegne av repre- sentantene Siv Jensen, Kari Kjønaas Kjos og meg selv vil President: Ø y v i n d K o r s b e r g jeg fremme et representantforslag om et styrket aktivitets- og folkehelsetilbud for mennesker med psykisk utviklings- D a g s o r d e n (nr. 74): hemming. 1. Muntlig spørretime 2. Ordinær spørretime Presidenten: Forslagene vil bli behandlet på regle- 3. Referat mentsmessig måte. Presidenten: Representanten Robert Eriksson vil framsette to representantforslag. S a k n r . 1 [10:03:55] Robert Eriksson (FrP) [10:00:44]: Jeg har først gle- Muntlig spørretime den av på vegne av representanten Ketil Solvik-Olsen og meg selv å fremsette et representantforslag om merverdi- Presidenten: Stortinget mottok mandag meddelelse avgiftskompensasjon for privatpersoner ved bygging av fra Statsministerens kontor om at statsrådene Grete omsorgsbolig for egne barn. Faremo, Anne-Grete Strøm-Erichsen og Heikki Eidsvoll Så har jeg også gleden av å fremsette et representant- Holmås vil møte til muntlig spørretime. forslag på vegne av representantene Laila Marie Reiertsen, De annonserte regjeringsmedlemmene er til stede, og vi Vigdis Giltun og meg selv om et mer helhetlig, effektivt og er klare til å starte den muntlige spørretimen. brukervennlig Nav. Vi starter med første hovedspørsmål, fra representanten Per Sandberg. Presidenten: Representanten Laila Dåvøy vil framset- te et representantforslag. Per Sandberg (FrP) [10:04:28]: Mitt spørsmål går til justisministeren – hvis det var noen som lurte på det! Laila Dåvøy (KrF) [10:01:35]: På vegne av represen- Vi har en situasjon der kapasiteten i norske fengsler er tantene Line Henriette Hjemdal, Kjell Ingolf Ropstad og sprengt. -

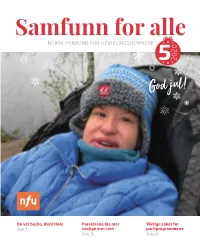

SFA Nr. 5 2020

Samfunn for alle NORSK FORBUND FOR UTVIKLINGSHEMMEDE 5 2020 v God jul! Du vet bedre, Bent Høie Foreldrene ble mer Viktige saker for Side 7 urolige enn Linn partiprogrammene Side 16 Side 20 FRA GENERALSEKRETÆREN Med ønske om likestilling mars ble tilværelsen snudd på hodet, nesten over I ettertid har VG hatt en rekke oppslag om hvordan natten. Det var nytt, ukjent og uvirkelig, men trøs- mennesker med utviklingshemning ble behandlet. I ten var kanskje at vi tenkte at dette ikke ville vare Stortingsrepresentanter og en jusprofessor har uttalt så lenge. Nå er det gått 9 måneder, og det er mange at dette ikke er en rettsstat verdig. Statsråder har uttalt steder i landet hvor man nå opplever at mye blir at man nå må påse at det samme ikke skal skje igjen. stengt ned igjen. Det gjelder å holde motet oppe. Det er viktig og bra å få slik støtte fra statsråder, De fleste syns nok det er vanskelig og tungt å stortingsrepresentanter, statlige organisasjoner og måtte forholde seg til de nasjonale påbud og anbefa- media, men hva med kommunene? Det er der vi alle Hedvig Ekberg linger som nå er strammet inn igjen. Man kan bli lever våre liv. Har de tatt dette innover seg slik at de Generalsekretær bekymret for hva dette vil medføre for hver enkelt av for fremtiden, pandemi eller ikke, sikrer at mennesker oss. Og det er forståelig, men NFU er spesielt bekym- med utviklingshemning ikke blir diskriminert og får ret for hvordan mennesker med utviklingshemning leve sine liv slik andre får? vil bli behandlet i kommunene. -

Childhood Comes but Once National Strategy to Combat Violence and Sexual Abuse Against Children and Youth (2014–2017)

Strategy Childhood comes but once National strategy to combat violence and sexual abuse against children and youth (2014–2017) Strategy Childhood comes but once National strategy to combat violence and sexual abuse against children and youth (2014–2017) 4 FOREWORD As a society, Norway has come a long way in its efforts to protect children and adolescents from violence, sexual abuse and bullying. The progress we have achieved is attributable to policy decisions, legislation, increased knowledge, public discussion, media attention and the work of professionals, parents and children themselves. We do not permit parents to harm their children, and we express collective grief and alarm when we hear of children exposed to serious abuse. To the vast majority of parents in Norway, nothing is more important than the well-being of children. All the same, violence and sexual abuse, whether in the family or elsewhere, are a part of daily life for many children. Extensive research shows how consequential violence may be, whether it is directed at a parent or the child itself, and whether it takes the form of direct physical violence, sexual abuse or bullying. Violence can lead to extensive cognitive, social, psychological and physical problems in both the short and long term. Violence against children and adolescents is a public health challenge. The approach to violence and sexual abuse against children in Norwegian society must be one of zero tolerance. We want safety and security for all children, enabling them to enjoy good health and a good quality of life as they grow. Taboos must be broken. -

(Nr. 16): 1. Innstilling

250 1. feb. – Forslag fra repr. Gabrielsen og Hernæs om endr. i ekspropriasjonserstatningsloven 2000 Møte tirsdag den 1. februar kl. 11.50 punkter er blitt svakere enn forutsatt av Stortinget da eks- propriasjonserstatningsloven ble vedtatt i 1984. Et tilsva- President: G u n n a r S k a u g rende forslag var et av flere som ble fremmet i 1996 ved Dokument nr. 8:87 for 1995-1996. Dagsorden (nr. 16): Komiteen peker i sine merknader på at forslaget gri- 1. Innstilling fra samferdselskomiteen om lov om end- per fatt i en sentral og sammensatt problemstilling, nem- ring i veglov 21. juni 1963 nr. 23 m.m. lig spørsmålet om hvilken betydning reguleringsplaner (Innst. O. nr. 41 (1999-2000), jf. Ot.prp. nr. 23 (1999- skal ha når det fastsettes erstatning for ekspropriasjon. 2000)) Komiteen mener at det er behov for en juridisk avklaring 2. Innstilling fra justiskomiteen om forslag fra stortings- før en tar endelig stilling til det fremlagte lovforslaget. representantene Ansgar Gabrielsen og Bjørn Hernæs Komiteen peker på at rettstilstanden når det gjelder om lov om endring i lov av 6. april 1984 nr. 17 om ve- forholdet mellom reguleringsplan og ekspropriasjonser- derlag ved oreigning av fast eigedom statninger, er et vanskelig og kontroversielt spørsmål. (Innst. O. nr. 39 (1999-2000), jf. Dokument nr. 8:66 Gode grunner tilsier at det kan være behov for å trekke (1998-1999)) opp en klarere grense som bidrar til å fjerne de mulige 3. Innstilling fra justiskomiteen om lov om endringer i uklarheter som i dag eksisterer. politiloven (den sentrale politiledelsen) Komiteen ber departementet opprette et eget utvalg (Innst. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Kartlegging Av Partienes Toppkandidaters Erfaring Fra Næringslivet Stortingsvalget 2021

Kartlegging av partienes toppkandidaters erfaring fra næringslivet Stortingsvalget 2021 I det videre følger en kartlegging av hvilken erfaring fra næringslivet toppkandidatene fra dagens stortingspartier i hver valgkrets har. Det vil si at i hver valgkrets, har alle de ni stortingspartiene fått oppført minst én kandidat. I tillegg er det kartlagt også for øvrige kandidater som har en relativt stor sjanse for å bli innvalgt på Stortinget, basert på NRKs «supermåling» fra juni 2021. I noen valgkretser er det derfor mange «toppkandidater». Dette skyldes at det er stor usikkerhet knyttet til hvilke partier som vinner de siste distriktsmandatene, og ikke minst utjevningsmandatene. Følgende to spørsmål har vært utgangspunktet for kartleggingen: 1. Har kandidaten drevet egen bedrift? 2. Har kandidaten vært ansatt daglig leder i en bedrift? Videre er kartleggingen basert på følgende kilder: • Biografier på Stortingets nettside. • Offentlig tilgjengelig informasjon på nettsider som Facebook, LinkedIn, Proff.no, Purehelp.no og partienes egne hjemmesider. • Medieoppslag som sier noe om kandidatenes yrkesbakgrunn. Kartleggingen har derfor flere mulige feilkilder. For eksempel kan informasjonen som er offentlig tilgjengelig, være utdatert eller mangelfull. For å begrense sjansen for feil, har kildene blitt kryssjekket. SMB Norge tar derfor forbehold om dette ved offentliggjøring av kartleggingen, eller ved bruk som referanse. Aust-Agder (3+1) Navn Parti Drevet egen bedrift? Vært daglig leder i en bedrift? Svein Harberg H Ja Ja Tellef Inge Mørland Ap Nei Nei Gro-Anita Mykjåland Sp Nei Nei Marius Aron Nilsen FrP Nei Nei Lætif Akber R Nei Nei Mirell Høyer- SV Nei Nei Berntsen Ingvild Wetrhus V Nei Nei Thorsvik Kjell Ingolf Ropstad KrF Nei Nei Oda Sofie Lieng MDG Nei Nei Pettersen 1 Akershus (18+1) Navn Parti Drevet egen bedrift? Vært daglig leder i en bedrift? Jan Tore Sanner H Nei Nei Tone W. -

Forhandlinger I Odelstinget Nr. 41 O 2001–2002 2002 573 Møte Mandag Den 30. September Kl. 12 President

Forhandlinger i Odelstinget nr. 41 2002 30. sep. – Referat 573 Møte mandag den 30. september kl. 12 8. lov om endringer i lov 16. juni 1972 nr. 47 om kontroll med markedsføring og avtalevilkår President: Å got Valle (markedsføringsloven) (Besl. O. nr. 56 (2001- 2002)) Dagsorden (nr. 38): 9. lov om endringer i skatteloven (ny ettårsregel) 1. Referat (Besl. O. nr. 54 (2001-2002)) 10. lov om endringer i lov 10. juni 1988 nr. 40 om fi- Statsrå d Erna Solberg overbrakte 19 nansieringsvirksomhet og finansinstitusjoner kgl. proposisjoner (se under Referat). mv. (omdanning av sparebanker til aksjeselskap eller allmennaksjeselskap) (Besl. O. nr. 55 Sak nr. 1 (2001-2002)) 11. lov om endringer i lov 9. mars 1973 nr. 14 om Referat vern mot tobakksskader (Besl. O. nr. 66 (2001- 1. (148) Lagtingets presidentskap melder at Lagtinget 2002)) har antatt Odelstingets vedtak til 12. lov om forbrukerkjøp (forbrukerkjøpsloven) 1. lov om endringar i skatte- og avgiftslovgivinga (Besl. O. nr. 67 (2001-2002)) (Besl. O. nr. 92 (2001-2002)) 13. lov om endringer i lov 4. februar 1960 nr. 2 om 2. lov om endringar i lov 4. juni 1954 nr. 2 om sprit, borettslag og lov 23. mai 1997 nr. 31 om eiersek- brennevin og isopropanol til teknisk og vitenska- sjoner (eierseksjonsloven) (Besl. O. nr. 87 pelig bruk m.v. (Besl. O. nr. 93 (2001-2002)) (2001-2002)) 3. lov om endringar i lov 8. juni 1984 nr. 59 om for- 14. lov om endringer i utlendingsloven (Besl. O. dringshavernes dekningsrett (dekningsloven) nr. 61 (2001-2002)) (Besl. O. nr. 94 (2001-2002)) 15. -

A Peace Nation Takes up Arms a Peace Nation Takes up Arms

Independent • International • Interdisciplinary PRIO PAPER 7 gate Hausmanns Address: Visiting NO Grønland, 9229 PO Box (PRIO) Oslo Institute Research Peace A Peace Nation Takes Up Arms A Peace Nation Takes Up Arms The Norwegian Engagement in Afghanistan - 0134 Oslo, Norway Oslo, 0134 The Norwegian Engagement in Afghanistan Visiting Address: Address: Visiting NO Grønland, 9229 PO Box (PRIO) Oslo Institute Research Peace War (CSCW) Civil of Study the for Centre The Norwegian government Minister of Foreign Affairs in This paper is part of a series was fully behind the Opera- the new government gave his that examines the strategies of tion Enduring Freedom first presentation on the Nor- four NATO members in Af- (OEF), the US-led war against wegian contribution to the ghanistan: The US, the UK, 7 gate Hausmanns the Taliban regime and Al parliament. The main justifi- Germany and Norway. Each - Qaeda initiated in October cation for the Norwegian case study first contextualizes Norway Oslo, 0134 2001. By late November the commitment was the same as their Afghanistan engagement government had offered Nor- that which had informed the in light of the broader foreign wegian military resources, in- country’s security policy since policy concerns of the country cluding Special Forces, F-16 the late 1940s: that full sup- concerned, and then focuses on the development and ad- jet fighters and one Hercules port to the United States and ISBN: 7 www.studio Studio Design: justment of military strategy C-130 transport aircraft with to NATO was essential for a 978 in relation to other compo- - personnel. There was no prec- reciprocal security guarantee. -

Landbrukets Plass I Stortingspartienes Prioriteringer

Landbrukets plass i stortingspartienes prioriteringer En gjennomgang av enkelte saker i perioden 1997-2001 Odd Lutnæs Kortnotat 4 - 2001 NORGES BONDELAG ~ _No_rs___ k __~ ~ Landbrukssamvirke Landbrukets Utredningskontor Schweigaardsgt. 34C Pb 934 7 Grønland N-0135 OSLO 1lf 22 05 47 00 Fax: 22 17 23 11 E-post: [email protected] http://lu.landbrnk.no Forord Norges Bondelag ønsket årette oppmerksomheten mot stortingspartienes håndte1ing av enkelte viktige landbrukspolitiske saker i stortingsperioden 1997-2001. Landbrukets Utredningskontor har på den bakgrunn tatt for seg et utvalg saker, og sett nærmere på hvordan disse er blitt håndte1t i Stortinget. Utvalget av enmer og saker for gjennomgangen har skjedd i samarbeid med Norges Bondelag. Vi vil få takke de ansatte ved stortingsarkivet for rask og god hjelp for å framskaffe nødvendig informasjon for å få ferdigstilt notatet. Kortnotatet er ført i penn av Odd Lutnæs ved Landbrukets Utredningskontor, som også står ansvarlig for de opplysninger, slutninger og beh·aktninger som kommer fram i notatet. Vi takker Norges Bondelag for et interessant oppdrag. Oslo, juli 2001 Hanne Eldby Prosjektkoordinator Side l Innhold 1 mNLEDNING ..... ... ....... .. ............................... " .. " ....... " ....... " ... "" ....... .... " .. "." ....... ... 1 1.1 DET LANDBRUKSPOLITISKE KOMPROMISSET - LANDBRUKSMELDTNGEN """""."""".". 1 1.2 NORSK LANDBRUKSPOLITIKK M ER SAMMENSATT ENN SOM SÅ"""".""."."""".".""."" 2 1.3 LITT NÆRMERE OM VALGT METODE OG BRUKA V KILDER """" """"""""""""."""""" 2 2 SAKER TIL DRØFTING -

Velferdskonferansen 2012 - Programutkast Bekreftelse Er Mottatt Fra De Oppførte Personene, Med Mindre Annet Er Oppgitt

Velferdskonferansen 2012 - Programutkast Bekreftelse er mottatt fra de oppførte personene, med mindre annet er oppgitt. Mandag 21. mai 10.00 – 10.10: Åpning Kulturinnslag: Sara Ramin Osmundsen 10.10 – 12.30: Ulikhet og sosialt opprør Verden over foregår det en omfattende kamp om fordelingen av samfunnets ressurser og de verdiene som skapes gjennom arbeid. Fordelingen av verdiene i samfunnet er nært knyttet til demokratisk styring, omfordeling gjennom skattesystemet og eksistensen av universelle offentlige ytelser som kommer alle til gode. I siste instans dreier det seg om fordelingen av økonomisk og politisk makt. Navn: Sue Christoforou, The Equality Trust Josefin Brink, Riksdagsmedlem Vänsterpartiet Rolf Aaberge, seniorforsker SSB Politikerdebatt- Finanspolitiske talspersoner: Knut Storberget (AP) (bekreftet), Jan Tore Sanner (H) (ikke bekreftet), Inga Marte Thorkildsen (SV)(bekreftet), Per Olaf Lundteigen (SP) (bekreftet), Borghild Tenden (V) (ikke bekreftet), Torstein Dahle (Rødt) (bekreftet), Kjetil Solvik Olsen (Frp) (ikke bekreftet), Hans- Olav Syversen, (Krf) (ikke bekreftet) Møteleder: Nina Hansen, journalist og forfatter Lunsj 13.30 – 15.30: Parallellseminar A A1: Forskjells-Norge Økonomisk utjevning kommer ikke av seg selv. Det er resultat av en samfunnsmessig kamp. I Norge, som i mange andre land, førte denne kampen til oppbygging av en omfattende offentlig sektor, et skattesystem som omfordeler og et sentralt lønnsforhandlingssystem som har bidratt til at inntekt fordeles jevnere. Utviklingen av universelle tjenester ga like rettighetter til utdanning, helsetjenester og sosiale ytelser for alle, samt lik tilgang til grunnleggende infrastruktur. Hvordan har utviklingen vært i Norge? Hva er situasjonen i dag? Hva er grepene for en rettferdig fordeling? Navn: (Avventer booking til plenumsinnlederne er på plass for å sikre at dette seminaret skiller seg fra plenumsinnledninga. -

Politisk Regnskap for 2010

VENSTRES STORTINGSGRUPPE POLITISK REGNSKAP 2010 Miljø, kunnskap, nyskaping og fattigdoms- bekjempelse Oslo, 23.06.10 Dokumentet finnes i klikkbart format på www.venstre.no 2 1. STORTINGSGRUPPA Venstres stortingsgruppe består i perioden 2005-09 av Trine Skei Grande (Oslo) og Borghild Tenden (Akershus). Trine Skei Grande er representert i kirke-, utdannings- og forskningskomiteen og kontroll- og konstitusjonskomiteen. Borghild Tenden er representert i finanskomiteen. Abid Q. Raja har møtt som vararepresentant for Borhild Tenden i perioden 1. til 16. oktober 2009, 30. november til 5. desember 2009 og fra 17. til 25. mars 2010. Stortingsgruppa har seks ansatte på heltid. 2. VIKTIGE SAKER FOR STORTINGSGRUPPA Venstres stortingsgruppe har valgt noen områder hvor vi mener det er behov for en mer offensiv og tydligere kurs. Ved siden av å forsvare liberale rettigheter har Venstres stortingsgruppe denne perioden derfor prioritert kunnskap, miljø og selvstendig næringsdrivende. Denne prioriteringen er synlig både i Venstres alternative budsjetter, i forslag som er fremmet på Stortinget og spørsmål som er stilt til statsrådene. I tillegg har Venstres stortingsgruppe vist at vi vil prioritere mer til dem som trenger det mest; både gjennom representantforslag for å bekjempe fattigdom hos barn, en bedre rusbehandling og et bedre barnevern. Venstre fremmet også et eget forslag om en velferdsreform som ble behandlet sammen med samhandlingsreformen. På Venstres landsmøte tidligere i år pekte Venstres nyvalgte leder, Trine Skei Grande, på fem utvalgte områder som vil være Venstres hovedprioritet den kommende tiden. Hun lovet at Venstre skal prioritere en milliard mer årlig til lærere, forskning, selvstendig næringsdrivende og småbedrifter, jernbane og for å bekjempe fattigdom. -

Innst. 257 S (2009–2010) Innstilling Til Stortinget Fra Finanskomiteen

Innst. 257 S (2009–2010) Innstilling til Stortinget fra finanskomiteen Dokument 8:112 S (2009–2010) Innstilling fra finanskomiteen om representant- gen, fra Fremskrittspartiet, Ulf Leir- forslag fra stortingsrepresentantene Borghild stein, Jørund Rytman, Kenneth Tenden og Trine Skei Grande om tiltak for å øke Svendsen og Christian Tybring-Gjedde, bruken av elbiler fra Høyre, Gunnar Gundersen, Arve Kambe og Jan Tore Sanner, fra Sosia- listisk Venstreparti, Lars Egeland, fra Til Stortinget Senterpartiet, Per Olaf Lundteigen, fra Kristelig Folkeparti, Hans Olav Syver- sen, og fra Venstre, Borghild Tenden, Sammendrag viser til at finansministeren har avgitt uttalelse om forslaget til finanskomiteen i brev av 30. april 2010. Stortingsrepresentantene Borghild Tenden og Brevet følger som vedlegg til denne innstillingen. Trine Skei Grande fremmet 14. april 2010 følgende forslag: Komiteens flertall, alle unntatt medlem- mene fra Høyre, Kristelig Folkeparti og Venstre, «I viser til at det i dag finnes sterke insentiver til å velge Stortinget ber regjeringen, i forbindelse med elbil. Gjennom avgiftssystemet er elbil fritatt for statsbudsjettet for 2011, opprette en tilskuddsordning engangsavgift, merverdiavgift og veibruksavgift. I for å stimulere til økt bruk av elbiler i offentlig flåte- tillegg ilegges elbil den laveste årsavgiftssatsen. Det drift. finnes også en rekke andre gunstige ordninger for elbileiere, som for eksempel rett til å kjøre i kollek- II tivfelt, gratis parkering og fri passering i bomringer. Til sammen utgjør dette en vesentlig støtte til kjøp og Stortinget ber regjeringen fjerne moms på leasing bruk av elbiler. av elbiler i forbindelse med revidert statsbudsjett for 2010.» F l e r t a l l e t viser til finansministerens vedlagte brev til komiteen der forslagene fra representantene Tenden og Skei Grande kommenteres.