1995 Edition Lawrence Goodwin Dorothy L Hajdu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Council Agenda

CITY of NOVI CITY COUNCIL Agenda Item D December 18, 2017 SUBJECT: Approval of recommendation from the Consultant Review Committee to award the Agreement for Civil Engineering Private Development Field Services to Spalding DeDecker for a five-year term and adoption of associated fees and charges, effective December 18,2017. SUBMITTING DEPARTMENT: Department of Public Services, Engineering Division CITY MANAGER APPROVAL: ~~ BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The contract with the City's current consultant for civil engineering field services for private development projects, Spalding DeDecker Associates, Inc. (SDA), expires on December 17, 2017. This consultant primarily provides engineering services related to private development, such as review of residential plot plans, construction inspection, project closeout paperwork assistance, and the completion of record drawings. The current contract was awarded at the April 23, 2012 City Council meeting and became effective on May 1, 2012 as a two-year contract. This contract has been extended four times, most recently on February 6, 2017. The pending expiration of the contract resulted in the City issuing a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) to consulting engineering firms. Listing minimum qualifications helped to ensure the responding firms met certain critical criteria, such as staff credentials, number of qualified staff, distance from the City, and relevant municipal experience. The RFQ was posted publicly and resulted in responses from three firms. The review process consisted of two components: 1) reviewing and scoring each of the qualifications; and 2) opening sealed fee proposal forms from the most qualified firm(s). The three submittals were evaluated by staff from Public Services, Community Development and Finance Departments, using the Qualifications Based Selection (QBS) process, with an emphasis on each firm's experience and understanding of the scope. -

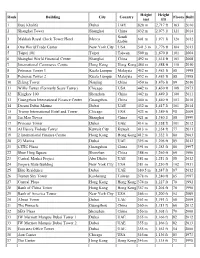

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

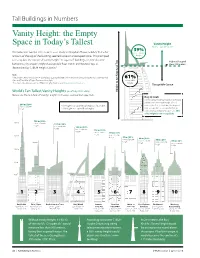

Vanity Height: the Empty Space in Today's Tallest

Tall Buildings in Numbers Vanity Height: the Empty Space in Today’s Tallest Vanity Height Non-occupiable Space 39% We noticed in Journal 2013 Issue I’s case study on Kingdom Tower, Jeddah, that a fair non-occupiable amount of the top of the building seemed to be an unoccupied spire. This prompted height us to explore the notion of “vanity height ” in supertall1 buildings, i.e., the distance Highest Occupied between a skyscraper’s highest occupiable fl oor and its architectural top, as Floor: 198 meters determined by CTBUH Height Criteria.2 Note: 1Historically there have been 74 completed supertalls (300+ m) in the world, including the now-demolished 61% One and Two World Trade Center in New York. occupiable 2 For more information on the CTBUH Height Criteria, visit http://criteria.ctbuh.org height Occupiable Space World’s Ten Tallest Vanity Heights (as of July 2013 data) Top Architectural to Height Below are the ten tallest “Vanity Heights” in today’s completed supertalls. Burj Al Arab With a vanity height of nearly 124 meters within its architectural height of 321 244 m | 29% meters, the Burj Al Arab has the highest non-occupiable * The highest occupied fl oor height as datum line. height ** The highest occupied fl oor height. non-occupiable-to-occupiable height ratio among completed supertalls. 39% of its height is non-occupiable. 133 m | 30% 200 m non-occupiable 131 m | 36% height non-occupiable 124 m | 39% height non-occupiable 113 m | 32% height non-occupiable 99 m | 31% height 150 m non-occupiable height 97 m | 31% 96 m | 29% non-occupiable -

Signature Redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015

TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE ARCHIVES 1 by MASSACM I 1TT;r OF 1*KCHN0L0LGY Wenjia Gu JUL 02 2015 B.S. Civil Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 LIBRAR IES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN CIVIL ENGINEERING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2015 C2015 Wenjia Gu. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redacted Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 21, 2015 Certified by: Signature redacted ( Jerome Connor Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted bv: Signature redacted ?'Hei4 Nepf Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students TRENDS AND INNOVATIONS IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS OVER THE PAST DECADE by Wenjia Gu Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 21, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT Over the past decade, high-rise buildings in the world are both booming in quantity and expanding in height. One of the most important reasons driven the achievement is the continuously evolvement of structural systems. In this paper, previous classifications of structural systems are summarized and different types of structural systems are introduced. Besides the structural systems, innovations in other aspects of today's design of high-rise buildings including damping systems, construction techniques, elevator systems as well as sustainability are presented and discussed. -

Of Quantities

MODULE 5 DESCRIBING VARIABILITY OF QUANTITIES The lessons in this module build on the data displays that you have used in elementary school, namely line plots, bar graphs, and circle graphs. You will be introduced to the fi eld of statistics, the study of data, and the statistical problem-solving process. You will calculate numerical summaries to describe a data set. You will also learn what separates mathematical and statistical reasoning—the presence of variability. Topic 1 The Statistical Process M5-3 Topic 2 Numerical Summaries of Data M5-67 CC01_SE_M05_INTRO.indd01_SE_M05_INTRO.indd 1 11/12/19/12/19 88:17:17 PMPM CC01_SE_M05_INTRO.indd01_SE_M05_INTRO.indd 2 11/12/19/12/19 88:17:17 PMPM TOPIC 1 The Statistical Process On average, one out of every 25 sheep has black wool. A quick way to estimate the size of a fl ock of sheep is to count the black sheep and multiply by 25. Lesson 1 What's Your Question? Understanding the Statistical Process . M5-7 Lesson 2 Get in Shape Analyzing Numerical Data Displays . M5-25 Lesson 3 Skyscrapers Using Histograms to Display Data . M5-47 CC01_SE_M05_T01_INTRO.indd01_SE_M05_T01_INTRO.indd 3 11/12/19/12/19 88:17:17 PMPM CC01_SE_M05_T01_INTRO.indd01_SE_M05_T01_INTRO.indd 4 11/12/19/12/19 88:17:17 PMPM Carnegie Learning Family Guide Course 1 Module 5: Describing Variability of Quantities TOPIC 1: THE STATISTICAL Where have we been? PROCESS In grade 1, students were expected to In this topic, students are introduced to organize, represent, and interpret data with the statistical problem-solving process: up to three categories. -

The Hows, Whats and Wows of the Willis Tower a Guide for Teachers Skydeck Chicago

THE HOWS, WHATS AND WOWS OF THE WILLIS TOWER A GUIDE FOR TEACHERS SKYDECK CHICAGO PROPERTY MANAGED BY U.S. EQUITIES ASSET MANAGEMENT LLC WELCOME TO SKYDECK CHICAGO AT WILLIS TOWER THE NATION’S TALLEST SCHOOL When you get back to your school, we hope your students will send us photos or write or create There are enough impressive facts about the Willis artwork about their experiences and share them Tower to make even the most worldly among us with us (via email or the mailing address at the end say, “Wow!” So many things at the Willis Tower can of this guide). We’ve got 110 stories already, and we be described by a superlative: biggest, fastest, would like to add your students’ experiences to our longest. But there is more to the building than all collection. these “wows”: 1,450 sky-scraping, cloud-bumping feet of glass and steel, 43,000 miles of telephone One photo will be selected as the “Photo of the cable, 25,000 miles of plumbing, 4.56 million Day” and displayed on our Skydeck monitors for all square feet of floor space and a view of four states. to see. Artwork and writing will posted on bulletin boards in the lunchroom area. Your students also Behind the “wows” are lots of “hows” and “whats” can post their Skydeck Chicago photos to the Willis for you and your students to explore. In this Tower or Skydeck Chicago pages on flickr, a free guide you will be introduced to the building—its public photo-sharing site: http://www.flickr.com/ beginnings as the Sears Tower and its design, photos/tags/willistower/ or http://www.flickr.com/ construction and place in the pantheon of photos/skydeckchicago/ skyscrapers. -

Image and Perception of the Top Five American Tourist Cities As Represented by Snow Globes Caitlin Malloy

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Architecture 5-2017 Image and Perception of the Top Five American Tourist Cities as Represented by Snow Globes Caitlin Malloy Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Marketing Commons, Other Architecture Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Malloy, Caitlin, "Image and Perception of the Top Five American Tourist Cities as Represented by Snow Globes" (2017). Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses. 19. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. IMAGE AND PERCEPTION OF THE TOP FIVE AMERICAN TOURIST CITIES AS REPRESENTED BY SNOW GLOBES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program of the Department of Architecture in the School of Architecture + Design Caitlin Lee Malloy May 2017 University of Arkansas at Fayetteville Professor Frank Jacobus Thesis Director Professor Windy Gay Doctor Ethel Goodstein-Murphree Committee Member Committee Member ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am so grateful for my time at the Fay Jones School of Architecture + Design – during the past five years, I have had the opportunity to work with the best faculty and have learned so much. My thesis committee in particular has been so supportive of my academic endeavors. My deepest appreciation for my committee chair, Frank Jacobus. -

John Hancock 600000 Visitors Aon Center Unlimited

Aon iconic Pathwayto Possible Chicago, IL Lakeshore east facts Lakeshore East N Cityfront Plaza Dr r D r e w E Hubbard St o L e r N Park Dr N Rush St N New St o e 13,210,000 SF v E Lower No A rth W ater St E North Water St office space n N Wabash Ave t a e S N McClurg Ct zi g E Kin i h N Lake Sh c i 41 r M E River Dr we Chicago River o N Columbus Dr 63,790 L N business population e v A n E Irv Kupcinet Brg E Low W er W l a acker D cker r e Dr ga i v e h L c Chicago i E W e ack M er c Se 8,063 rvi E Wacker Dr i ce Le r vel v E Wacker Dr e r residential units e p p S U n o N N s Breakwater Acc t e t S E Waterside Dr Dr N E Wacker Pl E South Water St N Field Dr s 3,839Lake E Lower South Water St u b hotelMichigan rooms m E South Water St N Westshore Dr u l E Haddock Pl o C N r N Harbor Dr e Lake Shore L w t a e o k C r b v East Park N H e L a d o A S n 1,532,565 SF r E Lake S t N N Park Dr h a h S l s o r e y a SF New Developments a r t r i b e E Benton Pl v r G a i o D N Field Blvd c N W h e r t u N L A E Benton Pl e T 41 v I e S l N A N Stetson Ave N Beaubien Ct $124,000 R T Average INcome o g E Lower Randolph St E R andolph St a t c N Upper Columbus Dr S h St i E Upper Randol p h E Randolp h E Randolph St C N Cultural M Millenium Grant i Center c h 15,000 i Park Park g an Daily Park Visitors A v Date: 8/20/2015 e E Washington St N Columbus Dr Miles 0 0.025 0.05 0.075 0.1 2 Data contained herein was compiled from sources deemed to be reliable. -

Typologies and Evaluation of Outdoor Public Spaces at Street Level of Tall Buildings in Chicago

TYPOLOGIES AND EVALUATION OF OUTDOOR PUBLIC SPACES AT STREET LEVEL OF TALL BUILDINGS IN CHICAGO Abstract Authors Zahida Khan and Peng Du Outdoor public spaces are key to human interactions, promoting Illinois Institute of Technology public life in cities. The constant increase in world population has led Keywords to increased tall urban conditions making the study of outdoor public Public spaces, tall buildings, urban forms, rating system spaces around tall buildings very popular. This paper outlines typol- ogies for outdoor public spaces occurring at street level of tall build- ings in downtown Chicago, the birthplace of skyscrapers and an ideal case study for an American city. The study uses online data archives, Google Maps, and on-site surveys as research techniques for the analysis. The result depicts around 50% of all the tall buildings in Chicago foster public life at its street level through public spaces. The other key finding is the outline of seven typologies based on their position around the tall building. Further, a comparative analysis is conducted using one example of each typology based on three crite- ria adopted from ‘Project for Public Spaces,’ namely (1) Accessibility; (2) Design and Comfort, and (3) Users and Activities. Prometheus 04 Buildings, Cities, and Performance, II Introduction outdoor public spaces, including: (A) Accessibility, (B) Design & Comfort, (C) Users & Activities, (D) Environ- Outdoor public spaces at street level of tall buildings play mental Sustainability, and (E) Sociable. The scope of this a significant role in sustainable city development. The research is limited to the first three design criteria since rapid increase in world population and constant growth of the last two require a bigger timeframe and is addressed urbanization has led many scholars to support Koolhaas’ for future research. -

Wearing Buildings Is It Possible to Wear a Building?

th 4 Grade Fine Arts ILS —25A, 26B, 27B Wearing Buildings Is it possible to wear a building? Theme Vocabulary This lesson engages students in researching, designing, and then Beaux-Arts (pronounced bow - ZAR) constructing a wearable model of a structure. (bow rhymes with dough) Beaux-Arts means “fine arts” in French; it is a Student Objectives style of architecture popular in France use imagination and hand-eye coordination to create a costume that and the United States in the late 19th th looks like a building and early 20 Century; buildings in this style typically have formal symmetrical floor plans, lots of Activities ornamentation, and classical features design and construct a “wearable” building borrowed from ancient Greek and Roman architecture Type façade (pronounced fah - SOD) the indoor, classroom activities with room to spread out front of a building texture the way a material looks Timeframe Grade Fine Arts and feels th three class sessions of 40 minutes each 4 rhythm parts of the building that visually move your eye along Materials 447 • Handout A - photograph of an architect dressed as the Chrysler Building pattern something that repeats; • materials for creating buildings: a variety of large boxes or cardboard pieces, typically windows or bricks on a building grocery store paper bags (for small children with narrow shoulders), or large paper yard bags (for larger children with wider shoulders) • a collection of recycled materials: yarn, egg cartons, paper towel tubes, scraps of cloth, etc. • crayons or markers Buildings Wearing • colored construction paper • scissors • glue • images of neighborhood buildings or Chicago structures for inspiration Teacher Prep display Handout A Schoolyards to Skylines © 2002 Chicago Architecture Foundation Background Information for Teacher Architects and architecture schools have a long tradition of gathering together to celebrate their profession. -

Rank Building City Country Height (M) Height (Ft) Floors Built 1 Burj

Rank Building City Country Height (m) Height (ft) Floors Built 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 Makkah Royal Clock 2 Mecca Saudi Arabia 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Tower Hotel 3 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m[5] 1,670 ft 101 2004 Shanghai World 4 Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 Financial Center International 5 Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 Commerce Centre Petronas Towers 1 6 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 and 2 Nanjing Greenland 8 Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 Financial Center 9 Willis Tower Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 10 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 98 2011 Guangzhou West 11 Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 Tower Trump International 12 Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 Hotel and Tower 13 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 14 Al Hamra Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,352 ft 77 2011 Two International 15 Hong Kong Hong Kong 416 m 1,364 ft 88 2003 Finance Centre 16 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012[F] 17 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 18 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 19 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 ft 102 1931 19 Elite Residence Dubai UAE 381 m 1,250 ft 91 2012[F] 21 Tuntex Sky Tower Kaohsiung Taiwan 378 m 1,240 ft 85 1994 Emirates Park Tower 22 Dubai UAE 376 m 1,234 ft 77 2010 1 Emirates Park Tower 22 Dubai UAE 376 m 1,234 ft 77 2010 2 24 Central Plaza Hong Kong Hong Kong 374 m 1,227 ft 78 1992[C] 25 Bank of China Tower Hong Kong Hong Kong 367 m 1,205 ft 70 1990 Bank -

Proliferation of the Tallest Building Syndrome: from Global to Local

Proliferation of the Tallest Building Syndrome: From Global to Local N. Naz Department of Architecture, University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore Abstract Since the dawn of human history, man has been striving hard to build high in order to make his mark on the world. Towers, pyramids, obelisks, cathedral’s steeples etc. are perhaps the earliest architectural statements of the human urge to reach to the sky. From the late 18th century, the Industrial Revolution brought drastic improvements in iron manufacturing and construction. William Le Baron Jenney, an American Engineer and architect, development of load-bearing steel frame, which led to the "Chicago skeleton" form of construction made possible variety of skyscrapers in the later years. His Home Insurance Company Building, in Chicago constructed in 1885 was the first one to employ the frame structure. This revolutionized urban life because in higher buildings greater number of people could have been accommodated in limited areas. Over the time, in being home to the worlds’ tallest building has become a major issue on the political agenda of many countries because of the stigma of economic prosperity and superiority attached to it. USA dominated the race for the title of the tallest building in the world during the first 90 years of 20th century. Malaysia acclaimed the title of housing the tallest building of the world in 1996 but soon after, Taiwan proclaimed the title in 2004. The futuristic contender is Dubai, UAE, where Burj Dubai is supposed to reach well over 2, 000 feet by the time it is completed in 2008.