Cypress Hills Ethnohistory and Ecology: a Regional Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Summary Report of the Geological Survey for the Calendar Year 1911

5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 SUMMARY REPORT OK THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF MINES FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1914 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT. OTTAWA PRTNTKD BY J. i»k L TAOHE, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT IfAJESTS [No. 26—1915] [No , 15031 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To Field Marshal, Hit Hoi/al Highness Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and of Strath-earn, K.G., K.T., K.P., etc., etc., etc., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Youb Royal Highness.,— The undersigned has the honour to lay before Your Royal Highness— in com- pliance with t>-7 Edward YIT, chapter 29, section IS— the Summary Report of the operations of the Geological Survey during the calendar year 1914. LOUIS CODERRK, Minister of Mines. 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To the Hon. Louis Codebrk, M.P., Minister of Mines, Ottawa. Sir,—I have the honour to transmit, herewith, my summary report of the opera- tions of the Geological Survey for the calendar year 1914, which includes the report* of the various officials on the work accomplished by them. I have the honour to be, sir, Your obedient servant, R. G. MrCOXXFI.L, Deputy Minister, Department of Mines. B . SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 5 GEORGE V. CONTENTS. Paok. 1 DIRECTORS REPORT REPORTS FROM GEOLOGICAL DIVISION Cairncs Yukon : D. D. Exploration in southwestern "" ^ D. MacKenzie '\ Graham island. B.C.: J. M 37 B.C. -

The Big Chill

THE BIG CHILL Royal Saskatchewan Museum THE BIG CHILL For further information please contact: Public Programs Royal Saskatchewan Museum 2445 Albert Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4W7 Email: [email protected] Website: www.royalsaskmuseum.ca © Royal Saskatchewan Museum 2012 The contents of this resource package may be reproduced for classroom use only. No portion may be duplicated for publication or sale. The following material provides teachers and students with information about the Ice Age in what is now Saskatchewan (remember, there was no such thing as Saskatchewan in those days!): • To describe Saskatchewan’s climate during the Ice Age. • To illustrate the geological effects of glaciation. • To recognize a variety of animals that lived in Saskatchewan during the Ice Age. Vocabulary advance geology climate glacier debris ice age deposit drumlin esker meltwater erratic moraine evaporation fauna retreat flora stagnant flow till fossil Laurentide Ice Sheet knob and kettle Wisconsin Glacial Period Pleistocene Epoch BACKGROUND INFORMATION Ice Ages The Ice Age or Pleistocene Epoch refers to the last two million years of our geological history when there were at least five periods of glaciation in North America. Gradual climate cooling caused huge continental ice sheets to form. Later, gradual warming caused these to melt during the interglacial periods. The last glacier began forming approximately 110,000 years ago, building until it covered all but the Cypress Hills and the Wood Mountain Plateau region of the Province. The last interglacial period started about 17,000 years ago. The ice sheet melted completely from our borders about 10,000 years ago. This last period of glaciation is called the Wisconsin Glacial Period. -

In the Matter of the Measurement and Apportionment of Thewaters of Thest

INTERNATIONALJOINT COMMISSION REARGUMENT IN THE MATTER OF THE MEASUREMENT AND APPORTIONMENT OF THEWATERS OF THEST. MARY AND MILK RIVERS ANDTHEIR TRIBUTARIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA UNDER ARTICLE VI OF THE TREATY OF JANUARY 1 I, 1909, BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN 4 OTTAWA, CANADA MAY 3, 4, AND 5, 1920 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1921 I. ,I,' #__? .. MAASUKIEMEW,. AM) APPOIITIO~~MEMOF THE WATERS OF THE ST. MARY ANT) MILK RIVERS. INTERNATIONALJOINTCOMMISSION, Ottawa, Canada,, May 9, 1920. The Commission met at 10 o'clock a. m. Present: C. A. Magrath (chairman for Ctinada) €1. A. Powell, K. c., Sir William Hearst. 0. Gardncr (chairman for tLe United States), Clarence D. Clark. Lawrcnce J. Burpee, secretary of the Commission for Canada. Ap earances : CoP . C. S. MacInnes, K. C., counsel for the Dominion of Canada, for the Provinces of Albertaand Saskatchewan, the WesternCanada Irrigation Association, andthe Cypress Hills Water-Users Association. Won. George Turner, counsel for the United States Government. Mr. Will R. Kin chief counsel for the United States Reclamation Service, with Mr. k. J. Egleston, of Helena, Mont., district counsel for the United StatesReclamation Service. with Mr. G. A. Walker of Calgary, for the States Senator from Montana. Mr. A. P. Davis,director of theUnited States Reclamation Service, Washin ton, D.. C. Mr. E. E'. Draf e, director, Reclamation Service of Canada, Ottawa. Mr. C. S. Heidel, hydrographer, engineer's office, State of Montana. Mr. R. J. Burley, irrigation engineer, Department of the Interior, Ottawa. Mr. C. H. Atwood, Water Power Branch, Department of the Inte- rior, Ottawa. -

Medicine Wheels

The central rock pile was 14 feet high with several cairns spanned out in different directions, aligning to various stars. Astraeoastronomers have determined that one cairn pointed to Capella, the ideal North sky marker hundreds of years ago. At least two cairns aligned with the solstice sunrise, while the others aligned with the rising points of bright stars that signaled the summer solstice 2000 years ago (Olsen, B, 2008). Astrological alignments of the five satellite cairns around the central mound of Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel from research by John A. Eddy Ph.D. National Geographic January 1977. MEDICINE WHEELS Medicine wheels are sacred sites where stones placed in a circle or set out around a central cairn. Researchers claim they are set up according to the stars and planets, clearly depicting that the Moose Mountain area has been an important spiritual location for millennia. 23 Establishing Cultural Connections to Archeological Artifacts Archeologists have found it difficult to establish links between artifacts and specific cultural groups. It is difficult to associate artifacts found in burial or ancient camp sites with distinct cultural practices because aboriginal livelihood and survival techniques were similar between cultures in similar ecosystem environments. Nevertheless, burial sites throughout Saskatchewan help tell the story of the first peoples and their cultures. Extensive studies of archeological evidence associated with burial sites have resulted in important conclusions with respect to the ethnicity of the people using the southeast Saskatchewan region over the last 1,000 years. In her Master Thesis, Sheila Dawson (1987) concluded that the bison culture frequently using this area was likely the Sioux/ Assiniboine people. -

Paleosols of the Interglacial Climates in Canada

Document generated on 09/28/2021 2:47 p.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire Paleosols of the Interglacial Climates in Canada Les paléosols du Canada au cours des périodes interglaciaires Paläoböden zur Zeit der Interglaziale in Kanada Charles Tarnocai The Last? Interglaciation in Canada Article abstract Le dernier (?) interglaciaire au Canada Although paleosols are useful indicators of paleoclimates. it is first necessary to Volume 44, Number 3, 1990 establish the relationships between the northern limits of the various contemporary soils and the pertinent climatic parameters. It is then necessary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032836ar to determine the age of the various paleosols and, if possible, their northern DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032836ar limits. Comparison of the distribution and northern limits of the contemporary soils with the distribution and northern limits of the analogous paleosols then permits the reconstruction of the paleoenvironments. For the purposes of See table of contents comparison the mean annual temperature of the Old Crow area during the Pliocene epoch was also determined (about 4°C) even though this was not an interglacial period. It was found that during the pre-lllinoian interglacial Publisher(s) periods the central Yukon had a mean annual temperature of about 7°C while during the Sangamonian interglacial period it had a mean annual temperature Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal of about - 3°C. During the Holocene epoch, the current interglacial period, the climate has been similar to or only slightly cooler than that existing during the ISSN Sangamonian interglacial period. The fluctuating position of the arctic tree line 0705-7199 (print) (and associated forest soils) during the Holocene epoch, however, indicates 1492-143X (digital) that the climate has also been fluctuating during this time. -

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek Introduction The bibliography was compiled from careful library and institutional searches. Accumulated titles were sent to various federal, provincial and municipal jurisdictions, academic institutions and foundations with a request for correction and additions. These included: Parks Canada in Ottawa, Winnipeg (Prairie Region) and Calgary (Western Region); Manitoba (Depart- ment of Culture, Heritage and Recreation); Saskatchewan (Department of Culture and Recreation); Alberta (Historic Sites Service); and British Columbia (Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services . The municipalities approached were those known to have an interest in heritage: Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, Regina, Moose Jaw, Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, Victoria, Vancouver and Nelson. Agencies contacted were Heritage Canada Foundation in Ottawa, Heritage Mainstreet Projects in Nelson and Moose Jaw, and the Old Strathcona Foundation in Edmonton. Various academics at the universities of Calgary and Alberta were also contacted. Historical Report Assessment Research Reports make up the bulk of both published and unpublished materials. Parks Canada has produced the greatest quantity although not always the best quality reports. Most are readily available at libraries and some are available for purchase. The Manuscript Report Series, "a reference collection of .unedited, unpublished research reports produced in printed form in limited numbers" (Parks Canada, 1983 Bibliography, A-l), are not for sale but are deposited in provincial archives. In 1982 the Manuscript Report Series was discontinued and since then unedited, unpublished research reports are produced in the Microfiche Report Series/Rapports sur microfiches. This will now guarantee the unavailability of the material except to the mechanically inclined, those with excellent eyesight, and the extremely diligent. -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

The Forest Vegetation of the Driftless Area, Northeast Iowa Richard A

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1976 The forest vegetation of the driftless area, northeast Iowa Richard A. Cahayla-Wynne Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Cahayla-Wynne, Richard A., "The forest vegetation of the driftless area, northeast Iowa" (1976). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16926. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16926 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The forest vegetation of the driftless area, northeast Iowa by Richard A. Cahayla-Wynne A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Botany and Plant Pathology Major: Botany (Ecology) Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 STUDY AREA 6 METHODS 11 RESULTS 17 DISCUSSION 47 SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 59 APPENDIX A: SPECIES LIST 60 APPENDIX B: SCIENTIFIC AND COMMON NAMES OF TREES 64 APPENDIX C: TREE BASAL AREA 65 1 INTRODUCTION Iowa is generally pictured as a rolling prairie wooded only along the water courses. The driftless area of northeast Iowa is uniquely contrasted to this image; northeast Iowa is generally forested throughout, often with rugged local relief. -

88 Reasons to Love Alberta Parks

88 Reasons to Love Alberta Parks 1. Explore the night sky! Head to Miquelon Lake Provincial Park to get lost among the stars in the Beaver Hills Dark Sky Preserve. 2. Experience Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area in the Beaver Hills UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. This unique 1600 square km reserve has natural habitats that support abundant wildlife, alongside agriculture and industry, on the doorstep of the major urban area of Edmonton. 3. Paddle the Red Deer River through the otherworldly shaped cliffs and badlands of Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park. 4. Wildlife viewing. Our parks are home to many wildlife species. We encourage you to actively discover, explore and experience nature and wildlife safely and respectfully. 5. Vibrant autumn colours paint our protected landscapes in the fall. Feel the crunch of fallen leaves underfoot and inhale the crisp woodland scented air on trails in many provincial parks and recreation areas. 6. Sunsets illuminating wetlands and lakes throughout our provincial parks system, like this one in Pierre Grey’s Lakes Provincial Park. 7. Meet passionate and dedicated Alberta Parks staff in a visitor center, around the campground, or out on the trails. Their enthusiasm and knowledge of our natural world combines adventure with learning to add value to your parks experiences!. 8. Get out in the crisp winter air in Cypress Hills Provincial Park where you can explore on snowshoe, cross-country ski or skating trails, or for those with a need for speed, try out the luge. 9. Devonshire Beach: the natural white sand beach at Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Park is consistently ranked as one of the top beaches in Canada! 10. -

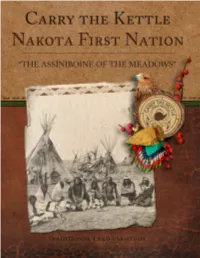

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Story Idea Als

Story Idea Krefeld, im Januar 2019 Historischer Familienspaß Geschichte zum Anfassen an Saskatchewans National Historic Sites Obwohl die Siedlungsgeschichte Kanadas für europäische Verhältnisse vergleichsweise jung ist, hat das Ahorn-Land viel Spannendes aus der Vergangenheit zu berichten! Verschiedene ausgewählte Bauwerke oder Naturdenkmäler, an denen sich einst signifikante Ereignisse zugetragen haben, zählen zu den kanadischen „National Historic Sites“. Sie illustrieren einige der entscheidendsten Momente in der Geschichte Kanadas. In den Sommermonaten lassen Mitarbeiter in zeitgenössischer Kleidung hier die Vergangenheit wieder aufleben. Mit bewegender Geschichte und spannenden Geschichten nehmen sie die Besucher auf eine interaktive Zeitreise mit. Auch in der Prärieprovinz Saskatchewan befinden sich einige dieser historischen Stätten, die Familienspaß für Jung und Alt versprechen. An der Batoche National Historic Site steht eine Zeitreise ins 19. Jahrhundert auf dem Programm. Am Ufer des South Saskatchewan River zwischen Saskatoon und Prince Albert gelegen, war Batoche nach seiner Gründung im Jahr 1872 eine der größten Siedlungen der Métis, d.h. der Nachfahren europäischer Pelzhändler und Frauen indigener Abstammung. Als sich die Métis gemeinsam mit lokalen Sippen vom Stamm der Cree und Assinoboine im Rahmen der Nordwest Rebellion gegen die kanadische Regierung auflehnten, war die Stadt im Jahr 1885 Schauplatz der entscheidenden Schlacht von Batoche. Noch heute sind an der Batoche National Historic Site die Einschlusslöcher der letzten Kämpfe zu sehen. Als Besucher kann man sich lebhaft vorstellen, wie sich die Widersacher seinerzeit auf beiden Seiten des Flusses in Vorbereitung auf den Kampf versammelten. Im Sommer locken hier verschiedene Events, wie beispielsweise das „Back To Batoche Festival“, das seit mehr als 50 Jahren jedes Jahr im Juli stattfindet und die Kultur und Musik der Métis zelebriert.