Ecosystem-Based Management Plan for Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

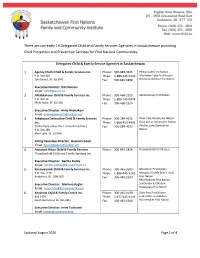

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

Summary Report of the Geological Survey for the Calendar Year 1911

5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 SUMMARY REPORT OK THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF MINES FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1914 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT. OTTAWA PRTNTKD BY J. i»k L TAOHE, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT IfAJESTS [No. 26—1915] [No , 15031 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To Field Marshal, Hit Hoi/al Highness Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and of Strath-earn, K.G., K.T., K.P., etc., etc., etc., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Youb Royal Highness.,— The undersigned has the honour to lay before Your Royal Highness— in com- pliance with t>-7 Edward YIT, chapter 29, section IS— the Summary Report of the operations of the Geological Survey during the calendar year 1914. LOUIS CODERRK, Minister of Mines. 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To the Hon. Louis Codebrk, M.P., Minister of Mines, Ottawa. Sir,—I have the honour to transmit, herewith, my summary report of the opera- tions of the Geological Survey for the calendar year 1914, which includes the report* of the various officials on the work accomplished by them. I have the honour to be, sir, Your obedient servant, R. G. MrCOXXFI.L, Deputy Minister, Department of Mines. B . SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 5 GEORGE V. CONTENTS. Paok. 1 DIRECTORS REPORT REPORTS FROM GEOLOGICAL DIVISION Cairncs Yukon : D. D. Exploration in southwestern "" ^ D. MacKenzie '\ Graham island. B.C.: J. M 37 B.C. -

The Big Chill

THE BIG CHILL Royal Saskatchewan Museum THE BIG CHILL For further information please contact: Public Programs Royal Saskatchewan Museum 2445 Albert Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4W7 Email: [email protected] Website: www.royalsaskmuseum.ca © Royal Saskatchewan Museum 2012 The contents of this resource package may be reproduced for classroom use only. No portion may be duplicated for publication or sale. The following material provides teachers and students with information about the Ice Age in what is now Saskatchewan (remember, there was no such thing as Saskatchewan in those days!): • To describe Saskatchewan’s climate during the Ice Age. • To illustrate the geological effects of glaciation. • To recognize a variety of animals that lived in Saskatchewan during the Ice Age. Vocabulary advance geology climate glacier debris ice age deposit drumlin esker meltwater erratic moraine evaporation fauna retreat flora stagnant flow till fossil Laurentide Ice Sheet knob and kettle Wisconsin Glacial Period Pleistocene Epoch BACKGROUND INFORMATION Ice Ages The Ice Age or Pleistocene Epoch refers to the last two million years of our geological history when there were at least five periods of glaciation in North America. Gradual climate cooling caused huge continental ice sheets to form. Later, gradual warming caused these to melt during the interglacial periods. The last glacier began forming approximately 110,000 years ago, building until it covered all but the Cypress Hills and the Wood Mountain Plateau region of the Province. The last interglacial period started about 17,000 years ago. The ice sheet melted completely from our borders about 10,000 years ago. This last period of glaciation is called the Wisconsin Glacial Period. -

Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada

COLONIAL CARCERALITY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: IMPRISONMENT, CARCERAL SPACE, AND SETTLER COLONIAL GOVERNANCE IN CANADA By JESSICA E. JURGUTIS B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Jessica E. Jurgutis, September 2018 i DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (2018) McMaster University (Political Science) Hamilton, ON TITLE: Colonial Carcerality and International Relations: Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada AUTHOR: Jessica E. Jurgutis, B.A. (McMaster University), M.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J. Marshall Beier NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 335 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the importance of colonial carcerality to International Relations and Canadian politics. I argue that within Canada, practices of imprisonment and the production of carceral space are a foundational method of settler colonial governance because of the ways they are utilized to reorganize and reconstitute the relationships between bodies and land through coercion, non-consensual inclusion and the use of force. In this project I examine the Treaties and early agreements between Indigenous and European nations, pre-Confederation law and policy, legislative and institutional arrangements and practices during early stages of state formation and capitalist expansion, and contemporary claims of “reconciliation,” alongside the ongoing resistance by Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. I argue that Canada employs carcerality as a strategy of assimilation, dispossession and genocide through practices of criminalization, punishment and containment of bodies and lands. Through this analysis I demonstrate the foundational role of carcerality to historical and contemporary expressions of Canadian governance within empire, by arguing land as indispensable to understanding the utility of imprisonment and carceral space to extending the settler colonial project. -

An Extra-Limital Population of Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys Ludovicianus, in Central Alberta

46 THE CANADIAN FIELD -N ATURALIST Vol. 126 An Extra-Limital Population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, in Central Alberta HELEN E. T REFRY 1 and GEOFFREY L. H OLROYD 2 1Environment Canada, 4999-98 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Canada; email: [email protected] 2Environment Canada, 4999-98 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Canada Trefry, Helen E., and Geoffrey L. Holroyd. 2012. An extra-limital population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, in central Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 126(1): 4 6–49. An introduced population of Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, Cynomys ludovicianus, has persisted for the past 50 years east of Edmonton, Alberta, over 600 km northwest of the natural prairie range of the species. This colony has slowly expanded at this northern latitude within a transition ecotone between the Boreal Plains ecozone and the Prairies ecozone. Although this colony is derived from escaped animals, it is worth documenting, as it represents a significant disjunct range extension for the species and it is separated from the sylvatic plague ( Yersina pestis ) that threatens southern populations. The unique northern location of these Black-tailed Prairie Dogs makes them valuable for the study of adaptability and geographic variation, with implications for climate change impacts on the species, which is threatened in Canada. Key Words: Black-tailed Prairie Dog, Cynomys ludovicianus, extra-limital occurrence, Alberta. Black-tailed Prairie Dogs ( Cynomys ludovicianus ) Among the animals he displayed were three Black- occur from northern Mexico through the Great Plains tailed Prairie Dogs, a male and two females, originat - of the United States to southern Canada, where they ing from the Dixon ranch colony southeast of Val Marie are found only in Saskatchewan (Banfield 1974). -

Future Possible Dry and Wet Extremes in Saskatchewan, Canada

!"#"$%&'())*+,%&-$.&/01&2%#& 34#$%5%)&*0&6/)7/#89%:/0;& </0/1/&& '$%=/$%1&>($	%&2/#%$&6%8"$*#.&?@%08.;&6/)7/#89%:/0& 3&29%/#(0;&A&A(0)/,;&B&2*##$(87&&CDEF&& 6G<&'"+&H&EFIJCKE3EF& & Future Possible Dry and Wet Extremes in Saskatchewan, Canada Prepared for the Water Security Agency, Saskatchewan E Wheaton Adjunct Professor, University of Saskatchewan and Emeritus Researcher, Saskatchewan Research Council Box 4061 Saskatoon, SK, 306 371 1205 B Bonsal Research Scientist, Environment Canada Adjunct Professor, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK V Wittrock Research Scientist, Saskatchewan Research Council Saskatoon, SK November 2013 2 L/+,%&(>&<(0#%0#)& !"##$%&' (! )*+%,-".+),*/',012.+)32'$*-'#2+4,-!' 5! !"#$%&'($)*+,-*.&/-0*12$+* 3! 4$&56-7*8'9$*:$2'6-)7*+,-*;$)$+2%5*<2+9$=62>* ?! .6)#$+2'27+%2#2!',8'+42')*!+%"#2*+$6'%2.,%-' 9! @26/A5&*B')&620*!($2('$=* C! DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*D($,&)*!($2('$=* G! 8"+"%2':,!!)062'-%,";4+!' <=! ./99+20*6H*:26"+"I$*+,-*J62)&K%+)$*@26/A5&*.%$,+2'6)* LG! 8"+"%2':,!!)062':%2.):)+$+),*'27+%2#2!' =<! M,&26-/%&'6,*+,-*!"#$%&'($* NL! ;$+)6,)*H62*O5+,A$)*',*&5$*B0-26I6A'%+I*O0%I$* NL! O5+,A$)*',*<2$P/$,%07*M,&$,)'&0*+,-*80F$*6H*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*DE&2$9$)* NN! :26#$%&'6,)*6H*DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,*H62*&5$*O+,+-'+,*:2+'2'$)* NQ! D)&'9+&$)*6H*4+E'9/9*:2$%'F'&+&'6,* NR! ./99+20*6H*:6))'"I$*+,-*J62)&KO+)$*</&/2$*.%$,+2'6)*6H*DE&2$9$*:2$%'F'&+&'6,* N3! "#$%&%'(!)*+*#(!,-+#(.(!"#(/010+&+0$2!3/(2�$4! 56! 7$#4+89&4(!,-+#(.(!)*+*#(!"#(/010+&+0$2!3/(2�$4! 56! .,*8)-2*.2')*'8"+"%2':%,12.+),*!' =9! -)!."!!),*'$*-'.,*.6"!),*!' =>! $.?*,@62-;2#2*+!' AB! %282%2*.2!' A<! 3 6MNN?GO& Droughts and extreme precipitation are extreme climate events and among the most costly and disruptive environmental hazards. -

Orchids of Lakeland

a field guide to OrchidsLakeland Provincial Park, Provincial Recreation Area and surrounding region Written by: Patsy Cotterill Illustrated by: John Maywood Pub No: I/681 ISBN: 0-7785-0020-9 Printed 1998 Sepal Sepal Petal Petal Seed Sepal Lip (labellum) Ovary Finding an elusive (capsule) orchid nestled away in Sepal the boreal forest is a Scape thrilling experience for amateur and Petal experienced naturalists alike. This type Petal of recreation has become a passion for Column some and, for many others, a wonder- ful way to explore nature and learn Ovary Sepal (capsule) more about the living world around us. Sepal But, we also need to be careful when Lip (labellum) looking at these delicate plants. Be mindful of their fragile nature... keep Spur only memories and take only photo- graphs so that others, too, can enjoy. Corm OrchidsMany people are surprisedin Alberta to learn that orchids grow naturally in Alberta. Orchids are typically associated with tropical rain forests (where indeed, many do grow) or flower-shop purchases for special occasions, exotic, expensive and highly ornamental. Wild orchids in fact are found world-wide (except in Antarctica). They constitute Roots Tuber the second largest family of flowering plants (the Orchidaceae) after the Aster family, with upwards of 15,000 species. In Alberta, there are 26 native species. Like all Roots orchids from north temperate regions, these are terrestrial. They grow in the ground, in contrast to the majority of rain forest species which are epiphytes, that is, they grow attached to trees for support but do not derive nourishment from them. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Paleosols of the Interglacial Climates in Canada

Document generated on 09/28/2021 2:47 p.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire Paleosols of the Interglacial Climates in Canada Les paléosols du Canada au cours des périodes interglaciaires Paläoböden zur Zeit der Interglaziale in Kanada Charles Tarnocai The Last? Interglaciation in Canada Article abstract Le dernier (?) interglaciaire au Canada Although paleosols are useful indicators of paleoclimates. it is first necessary to Volume 44, Number 3, 1990 establish the relationships between the northern limits of the various contemporary soils and the pertinent climatic parameters. It is then necessary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032836ar to determine the age of the various paleosols and, if possible, their northern DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032836ar limits. Comparison of the distribution and northern limits of the contemporary soils with the distribution and northern limits of the analogous paleosols then permits the reconstruction of the paleoenvironments. For the purposes of See table of contents comparison the mean annual temperature of the Old Crow area during the Pliocene epoch was also determined (about 4°C) even though this was not an interglacial period. It was found that during the pre-lllinoian interglacial Publisher(s) periods the central Yukon had a mean annual temperature of about 7°C while during the Sangamonian interglacial period it had a mean annual temperature Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal of about - 3°C. During the Holocene epoch, the current interglacial period, the climate has been similar to or only slightly cooler than that existing during the ISSN Sangamonian interglacial period. The fluctuating position of the arctic tree line 0705-7199 (print) (and associated forest soils) during the Holocene epoch, however, indicates 1492-143X (digital) that the climate has also been fluctuating during this time. -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

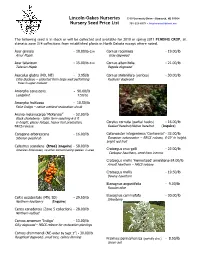

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Welcome to the Cypress Hills Grasslands Workshop Peterswain

Welcome to the Cypress Hills The island in the prairie plains An Interprovincial Park • The first Interprovincial Park in Canada • Three Separate Blocks – The West Block, Centre Block, and East Block • Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park spans the borders of two provinces, with three governments cooperating in the management of this unique geographical feature and ecosystem. • In 1989, Cypress Hills - Saskatchewan and Alberta - joined forces and created Canada’s first Interprovincial Park. The Interprovincial Park Agreement was amended in 2000 to formally include Fort Walsh National Historic Site. Cypress Hills… A perfect oasis in the desert we have traveled John Palliser, 1850 Protecting a Significant Place Systems Perspective: Environmental Diversity Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park Montane Foothills Fescue Dry Mixedgrass Mixedgrass Montane Distance = ~ 300 km2 Dark Sky Preserve • On September 28, 2004, a declaration was signed between the provinces on Saskatchewan and Alberta and the Government of Canada, in partnership with the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada to designate the Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park as a Dark-Sky Preserve. • Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park is the first park in Saskatchewan and Alberta to become fully recognized as a Dark-Sky Preserve in North America Cypress Hills Dark-Sky Preserve Geography • Formed by sedimentary layers, not faulting and folding, or uplifting like the Rockies. • Over 600 metres above the surrounding plains (though the hills are only 200 metres high) • Cypress Hills were a Nunatak