Medicine Wheels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Qualitative Examination of Historical Trauma and Grief Responses in the Oceti Sakowin Anna E

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Qualitative Examination of Historical Trauma and Grief Responses in the Oceti Sakowin Anna E. Quinn Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Quantitative Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Anna E. Quinn has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Benita Stiles-Smith, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Sharon Xuereb, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Victoria Latifses, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2019 Abstract Qualitative Examination of Historical Trauma and Grief Responses in the Oceti Sakowin by Anna E. Quinn MS, Walden University, 2011 BA, Dakota Wesleyan University, 2008 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Psychology Walden University February 2019 Abstract Past research regarding historical trauma in the Lakota, one of the three major groups of the Oceti Sakowin or Sioux, has contributed to the historical trauma theory, but gaps continue to exist. The purpose of the study was to examine the historical trauma experiences and grief responses of individuals who identify as Oceti Sakowin, specifically the Nakota and Dakota, including present experiences. -

Tribal Strategies Against Violence: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Tribal Strategies Against Violence: Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study Author(s): V. Richard Nichols ; Anne Litchfield ; Ted Holappa ; Kit Van Stelle Document No.: 206034 Date Received: June 2004 Award Number: 97-DD-BX-0031 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Tribal Strategies Against Violence Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes Case Study Prepared by ORBIS Associates V. Richard Nichols Principal Investigator Anne Litchfield Senior Researcher/Editor Ted Holappa Investigator Kit Van Stelle Criminal Justice Consultant January 2002 NIJ # 97-DD-BX0031 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, by ORBIS Associates under contract # 97-DD- BX 0031. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Historical Lewis and Clark, Pioneering Rangeland Managers? by Richard H

Historical Lewis and Clark, Pioneering Rangeland Managers? By Richard H. Hart wo hundred years ago, the “Corps of Discovery,” as also support large numbers of domestic livestock. On the the expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and other hand, Steven Long7 and John C. Fremont8 concluded William Clark was formally known, was well into that, although the Great Plains were unfit for crop agricul- the Northern Great Plains. They were not the first ture, they were excellent grazing lands. However, Lewis and TEuro-Americans to enter this region. Henry Kelsey had been Clark’s sighting of large numbers of bison nearly every day on the Saskatchewan River in 1690 or 1691 and described his and of bison on 19 of the 29 days they spent near the Great travels in verse of awkward rhyme and worse meter.1 Pierre Falls of the Missouri casts doubt on the regular migration of Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Vèrendrye, reached the bison and the rationale for rotational grazing.9 Mandan villages on the Missouri River in 1738. His sons, Although they frequently mentioned woody vegetation Louis-Joseph and François, traveled up the Missouri from the and the more showy forbs, Lewis and Clark rarely mentioned villages in 1742 and 1743, reaching the mouth of the Teton grass in general, and never, as far as I could find, mentioned a River.2 DeVoto describes several other explorations of the particular species of grass. Perhaps they viewed grass as out- Northern Plains before 1800.3 Representatives of the side the plant kingdom, as Fremont8 apparently did when he Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company had recorded “. -

Outline of United States Federal Indian Law and Policy

Outline of United States federal Indian law and policy The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to United States federal Indian law and policy: Federal Indian policy – establishes the relationship between the United States Government and the Indian Tribes within its borders. The Constitution gives the federal government primary responsibility for dealing with tribes. Law and U.S. public policy related to Native Americans have evolved continuously since the founding of the United States. David R. Wrone argues that the failure of the treaty system was because of the inability of an individualistic, democratic society to recognize group rights or the value of an organic, corporatist culture represented by the tribes.[1] U.S. Supreme Court cases List of United States Supreme Court cases involving Indian tribes Citizenship Adoption Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, 530 U.S. _ (2013) Tribal Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978) Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30 (1989) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) Civil rights Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313 (1978) Congressional authority Ex parte Joins, 191 U.S. 93 (1903) White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker, 448 U.S. 136 (1980) California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987) South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993) United States v. -

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek Introduction The bibliography was compiled from careful library and institutional searches. Accumulated titles were sent to various federal, provincial and municipal jurisdictions, academic institutions and foundations with a request for correction and additions. These included: Parks Canada in Ottawa, Winnipeg (Prairie Region) and Calgary (Western Region); Manitoba (Depart- ment of Culture, Heritage and Recreation); Saskatchewan (Department of Culture and Recreation); Alberta (Historic Sites Service); and British Columbia (Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services . The municipalities approached were those known to have an interest in heritage: Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, Regina, Moose Jaw, Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, Victoria, Vancouver and Nelson. Agencies contacted were Heritage Canada Foundation in Ottawa, Heritage Mainstreet Projects in Nelson and Moose Jaw, and the Old Strathcona Foundation in Edmonton. Various academics at the universities of Calgary and Alberta were also contacted. Historical Report Assessment Research Reports make up the bulk of both published and unpublished materials. Parks Canada has produced the greatest quantity although not always the best quality reports. Most are readily available at libraries and some are available for purchase. The Manuscript Report Series, "a reference collection of .unedited, unpublished research reports produced in printed form in limited numbers" (Parks Canada, 1983 Bibliography, A-l), are not for sale but are deposited in provincial archives. In 1982 the Manuscript Report Series was discontinued and since then unedited, unpublished research reports are produced in the Microfiche Report Series/Rapports sur microfiches. This will now guarantee the unavailability of the material except to the mechanically inclined, those with excellent eyesight, and the extremely diligent. -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

Dakota, Nakota, Lakota Life (Worksheets)

Dakota, Nakota, Lakota Life South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Dakota, Nakota, Lakota Life (Worksheets) Background Information: About 8.3% of South Dakotans hold dual citizenship. Most of the 64,000 American Indians living in South Dakota are members of the Lakota, Nakota and Dakota Nation (also known as the 1 Great Sioux Nation) as well as Americans. Lakota histories are passed from generation to generation through storytelling. One story tells about the Lakota coming to the plains to live and becoming Oceti Sakowin, the Seven Council Fires. The story begins when the Lakota lived in a land by a large lake where they ate fish and were warm and happy. A man appeared, and told them to travel northward. The Lakota obeyed, and began the journey north. On their way they got cold, and the sun was too weak to cook their food. Two young men had a vision, and following its instructions, they gathered dry grasses and struck two flint stones together, creating a spark and making fire. There were seven groups of relatives traveling together. Each group took some of the fire, and used it to build their own fire, around which they would gather. 2 As a result, they became known as the Seven Council Fires, or Oceti Sakowin. During the mid-17th century, nearly all the Sioux people lived near Mille Lacs, Minnesota.3 Pressured by the Chippewas, they moved west out of northern Minnesota in clan groups by the early 18th century.4 The three tribes spoke the same general language, but each developed dialects or variations, which also became their known name. -

Table of Contents

Dakota, Nakota, Lakota Life South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Goals and Materials 2 Photograph List 3-4 Books and CDs in the Kit 5 Music CDs and DVD in the Kit 6 Erasing Native American Stereotypes 7-8 Teacher Resource 9-18 Bibliography 19-20 Worksheets Word Find 21 Word Find Key 22 Crossword Puzzle 23 Crossword Puzzle Key 24 Word Scramble 25 Word Scramble Key 26 Activities Reading an Object 27-28 Object Identification Sheet 29-35 Trek to Wind Cave 36-37 South Dakota Coordinates Worksheet 38 Comparing Families 39-40 Comparing Families Worksheet 41 What Does the Photo Show? 42-43 Beadwork Designs 44-45 Beadwork Designs Worksheet 46 Beadwork Designs Key 47 Lazy Stitch Beading 48-49 Lazy Stitch Beading Instructions / Pattern 50-51 What Do You Get From a Buffalo? 52-53 Buffalo Uses Worksheet 54 Pin the Parts on the Buffalo 55-56 Pin the Parts on the Buffalo Worksheet 57 Pin the Parts on the Buffalo Worksheet Key 58 Pin the Parts on the Buffalo Outline & Key 59-60 Create a Ledger Drawing 61-62 Examples of Ledger Drawings 63-66 Traditional & Contemporary: Comparing Drum 67-68 Groups Come Dance With Us: Identifying Powwow Dance 69-72 Styles 1 Dakota, Nakota, Lakota Life South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Goals and Materials Goals Kit users will: explore the history and culture of the Dakota, Nakota and Lakota people understand the changes brought about by the shift from buffalo hunting to reservation life appreciate that the Dakota, Nakota and Lakota culture is not something -

Glossary Descriptions and Definitions of Some of the Concepts, Characters

Glossary Descriptions and definitions of some of the concepts, characters, places, nations and peoples mentioned on this site. A useful lexicon. CONCEPTS Dominion Land Surveyor Dominion Land Surveyors were sent out to western Canada by the federal government to divide Crown lands into square sections (cadastres) for agricultural and other purposes. Métis, métis Métis, with a capital M, means a member of the Métis nation, a person of mixed Indigenous (primarily Anishinaabe and Cree) and European (primarily French and Scottish) descent. Section 35 of the Constitution Act , 1982, recognized the Métis as Aboriginal people. The Métis constitute a nation not just legally, but socially: over time they have established a national consciousness, a distinctive identity, and their own culture and values. A person can self-identify as métis, a more generic term for a person of mixed heritage. This is an individual identity rather than an expression of membership in a distinctive culture with specific rights. Michif or mechif or mitchif Linguists classify Michif as a mixed language rather than a creole language, though there is some disagreement about this categorization. Michif emerged in the early 19 th century from the increasing contact between (French) Canadian fur traders and the Indigenous inhabitants of the Prairies, particularly the Cree. Michif typically consists of French nouns, numerals, articles and adjectives, combined with Cree syntax and verb structures. Michif was also influenced by Assiniboine and Nishnaabemwin, an eastern Ojibwa dialect. It was spoken by the Métis of western Canada and North Dakota. Like many languages around the world, Michif is slowly disappearing: currently, there are fewer than 1,000 Michif speakers in Canada. -

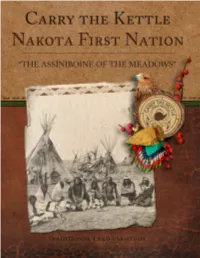

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Story Idea Als

Story Idea Krefeld, im Januar 2019 Historischer Familienspaß Geschichte zum Anfassen an Saskatchewans National Historic Sites Obwohl die Siedlungsgeschichte Kanadas für europäische Verhältnisse vergleichsweise jung ist, hat das Ahorn-Land viel Spannendes aus der Vergangenheit zu berichten! Verschiedene ausgewählte Bauwerke oder Naturdenkmäler, an denen sich einst signifikante Ereignisse zugetragen haben, zählen zu den kanadischen „National Historic Sites“. Sie illustrieren einige der entscheidendsten Momente in der Geschichte Kanadas. In den Sommermonaten lassen Mitarbeiter in zeitgenössischer Kleidung hier die Vergangenheit wieder aufleben. Mit bewegender Geschichte und spannenden Geschichten nehmen sie die Besucher auf eine interaktive Zeitreise mit. Auch in der Prärieprovinz Saskatchewan befinden sich einige dieser historischen Stätten, die Familienspaß für Jung und Alt versprechen. An der Batoche National Historic Site steht eine Zeitreise ins 19. Jahrhundert auf dem Programm. Am Ufer des South Saskatchewan River zwischen Saskatoon und Prince Albert gelegen, war Batoche nach seiner Gründung im Jahr 1872 eine der größten Siedlungen der Métis, d.h. der Nachfahren europäischer Pelzhändler und Frauen indigener Abstammung. Als sich die Métis gemeinsam mit lokalen Sippen vom Stamm der Cree und Assinoboine im Rahmen der Nordwest Rebellion gegen die kanadische Regierung auflehnten, war die Stadt im Jahr 1885 Schauplatz der entscheidenden Schlacht von Batoche. Noch heute sind an der Batoche National Historic Site die Einschlusslöcher der letzten Kämpfe zu sehen. Als Besucher kann man sich lebhaft vorstellen, wie sich die Widersacher seinerzeit auf beiden Seiten des Flusses in Vorbereitung auf den Kampf versammelten. Im Sommer locken hier verschiedene Events, wie beispielsweise das „Back To Batoche Festival“, das seit mehr als 50 Jahren jedes Jahr im Juli stattfindet und die Kultur und Musik der Métis zelebriert.