Translating Rubén Darío's Azul…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MONSTROSITY and IDENTITY in the COMEDIAS of LOPE DE VEGA Sarah Apffel Cegelski a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty at the Un

MONSTROSITY AND IDENTITY IN THE COMEDIAS OF LOPE DE VEGA Sarah Apffel Cegelski A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Romance Languages Department. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved By: Carmen Hsu Frank Dominguez Rosa Perelmuter Margaret Greer Valeria Finucci © 2015 Sarah Apffel Cegelski ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Sarah Apffel Cegelski: Monstrosity and Identity in the Comedias of Lope de Vega (Under the Direction of Carmen Hsu) Monstrosity and Identity in the Comedias of Lope de Vega is concerned with the relationship between monstrosity and identity formation in early modern Spain. The monster was a popular cultural phenomenon in sixteenth and seventeenth century Spain, appearing in a variety of scientific and literary genres. The monster was not just an extraordinary and unusual creature that elicited reactions of awe, wonder, and terror; it was also considered a sign from God that required careful interpretation to comprehend its meaning. The monster also embodies those characteristics that a society deems undesirable, and so by contrast, it shows what a society accepts and desires as part of its identity. In Lope de Vega’s (1562-1635) comedias, the playwright depicts characters who challenged the social, political, and religious conventions of his time as monsters. This study of Lope’s monsters intends to understand how and why Lope depicted these characters as monsters, and what they can tell us about the behaviors, beliefs, and traditions that Lope rejected as unacceptable or undesirable parts of the Spanish collective identity. -

El Concepto De Belleza En Las Rimas Y Rimas Sacras De Lope De Vega Miriam Montoya the University of Arizona

El concepto de belleza en las Rimas y Rimas Sacras de Lope de Vega Miriam Montoya The University of Arizona studiar a Lope de Vega implica hacer un breve recorrido sobre su vida debido a que en ésta se inspiró para escribir muchas de sus obras. En Eeste ensayo se hará un recuento de los sucesos históricos más sobresalientes del tiempo en que vivió este prolífico escritor. También se discutirán los aspectos más importantes de la época literaria y finalmente se hablará sobre el estilo de la poesía lírica de Lope para destacar varios aspectos que permitan entender el concepto de belleza en algunos poemas de sus obras Rimas (1602) y Rimas Sacras (1614). De acuerdo al estudio de Fernando Lázaro Carreter, Lope Félix de Vega Carpio nació en Madrid el 25 de noviembre de 1562. Sus padres, Félix de Vega Carpio y Francisca Fernández Flores eran procedentes de la Montaña y habían llegado a Madrid poco antes del nacimiento de Lope. Félix de Vega era un bordador de renombre que murió cuando Lope tenía quince años. De su madre sólo sabemos que vivió hasta 1589. Acerca de su niñez se sabe que entendía el latín a los cinco años. Además, fue estudiante de un colegio de la Compañía de Jesús donde en tan sólo dos años, dominó la Gramática y la Retórica. Sobre sus estudios universitarios, se cree que estuvo matriculado en la Universidad de Alcalá de 1577 a 1582 y quizás también en la de Salamanca. En el año de 1583, cuando tenía veintiún años, formó parte de la expedición a las Islas Azores para conquistar la última de éstas: La Terceira. -

A Little Book of Eternal Wisdom

A Little Book of Eternal Wisdom Author(s): Suso, Henry (1295-1366) Publisher: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne Ltd., London Description: ªThe Little Book of Eternal Wisdom is among the best of the writings of Blessed Henry Suso, a priest of the Order of St. Dominic, who lived a life of wonderful labours and sufferings, and died in the Fourteenth century with a reputation for sanctity which the Church has solemnly confirmed. It would be difficult to speak too highly of this little book or of its author. In soundness of teaching, sublimity of thought, clearness of expression, and beauty of illustration, we do not know of a spiritual writer that surpasses Henry Suso.ºÐfrom the introduction by C. H. McKenna Subjects: Practical theology Practical religion. The Christian life Mysticism i Contents Title 1 Preface 2 Foreword 3 The Parable of the Pilgrim 5 Translators Note 9 Preface 10 Little Book of Eternal Wisdom Title 13 First Part 14 Chapter I 15 Chapter II 17 Chapter III 20 Chapter IV 22 Chapter V 23 Chapter VI 26 Chapter VII 31 Chapter VIII 35 Chapter IX 36 Chapter X 39 Chapter XI 40 Chapter XII 42 Chapter XIII 46 Chapter XIV 50 Chapter XV 53 Chapter XVI 55 Chapter XVII 59 Chapter XVIII 62 ii Chapter XIX 64 Chapter XX 66 Second Part 67 Chapter XXI 68 Chapter XXII 74 Chapter XXIII 75 Chapter XXIV 83 Chapter XXV 84 Third Part 91 On Sunday, or at Matins 92 On Monday, or at Prime 93 On Tuesday, or at Tierce 94 On Wednesday, or at Sext 95 On Thursday, or at None 96 On Friday, or at Vespers 97 On Saturday, or at Compline 98 Indexes 100 Index of Scripture References 101 iii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. -

De Caupolicán a Rubén Darío

Miguel Ángel Auladell Pérez Profesor titular E.U. de literatura española de la Universidad de Ali- cante. Su actividad docente e in- vestigadora se ha centrado princi- palmente en la literatura española del siglo XVII y de la época de Fin de Siglo. Ha formado parte de va- rios proyectos de investigación, tanto de financiación pública como privada. Ha participado en nume- rosos congresos nacionales e inter- nacionales de su especialidad y ha DE CAUPOLICÁN A RUBÉN DARÍO publicado artículos sobre diversos MIGUEL ÁNGEL AULADELL PÉREZ escritores barrocos (Liñán y Verdu- go, Lope de Vega, Ruiz de Alarcón, Calderón) y finiseculares (Rubén Darío, Azorín). Es autor de la mo- nografía titulada La 'Guía y avisos de forasteros que vienen a la Cor te ' del Ldo. Antonio Liñán y Verdu go en su contexto literario y editor Rubén Darío publicó su conocido «Cau- Se ha repetido hasta la saciedad que Rubén del Ensayo bio-bibliográfico de es critores de Alicante y su provincia policán» en el diario santiaguino La Época el habría introducido nuevos textos en^lz^L. pa- de Manuel Rico García. Asimismo, 11 de noviembre de 1888. Bajo el título de «El ra tratar de paliar en lo posible la acusación de ha editado una Antología de poesía y prosa de Rubén Darío. Actual- Toqui», venía acompañado de otros dos sone- «galicismo mental» que le había propinado mente, dirige la edición digital de tos, «Chinampa» y «El sueño del Inca», agru- Juan Valera en dos de sus Cartas americanas di- la obra de Lope de Vega en la Bi- blioteca Virtual Cervantes. -

Al Biles & Genjam Song List

Al Biles & GenJam Song List Song Title Composer Style Song Title Composer Style Gimme Five Abercrombie, John 5 Pumston Neverland Biles, Al Slow Work Song Adderley, Nat Pop Rake, The Biles, Al 7 Nature Boy/Mad Men ahbez, eden MovTV All Over Again Blanchard, Terrance Latin Rise Alpert, Herb Waltz Wherever You Might Go Boehlee, Karel Bossa Serenata Anderson, Leroy Pop Do It Again Bolden, Walter Slow Affreusement Votre Ansallem, Franck Pop Black Orpheus Bonfa, Luis MovTV Look of Love Bacharach, Burt MovTV Gentle Rain Bonfa, Luis Bossa Goodbye Barbieri, Gato MovTV Dhyana Brooks, Tina Med It's Over Barbieri, Gato 16 Good Old Soul Brooks, Tina Slow Jeanne Barbieri, Gato Waltz Gypsy Blue Brooks, Tina Latin Last Tango in Paris Barbieri, Gato MovTV Open Sesame Brooks, Tina Fast Sun Shower Barron, Kenny Latin Street Singer Brooks, Tina Slow Brazil Barroso, Ary 16 Theme for Doris Brooks, Tina Fast Diamonds Are Forever Barry, John MovTV Waiting Game Brooks, Tina Fast Thunderball Barry, John MovTV Episode fm Village Dance Brown, Donald Latin Jive at Five Basie, Count Med Far More Blue Brubeck, Dave 5 Mambo Inn Bauza, Maurio Latin French Spice Byrd, Donald Med What Now My Love Becaud, Gilbert Bossa Secrets of Love Cables, George Pop Putcha-Putcha Benson, Warren Slow Think on Me Cables, George Latin Johnny Staccato Bernstein, Elmer 5 What U Won't Do 4 Luv Caldwell, Bobby Pop AGT Blues Biles, Al Latin Windflower Cassey, Sara Slow Analog Blues Biles, Al 12 Cool Struttin’ Clark, Sonny Slow Even Dozen Odd Biles, Al 5 Dial S for Sonny Clark, Sonny Med Gentle Descent Biles, Al 16 Melody for C Clark, Sonny Med Here's How Biles, Al Slow News for Lulu Clark, Sonny Med Lady Bug Biles, Al Med Sonny's Mood Clark, Sonny Slow Last Tangle Biles, Al Pop Blessing, The Coleman, Ornette Med Lovey Biles, Al 5 Giant Steps Coltrane, John Fast Minor Changes Biles, Al Fast Louisiana Fairy Tale Coots, J. -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

Towards a Philological Metric Through a Topological Data Analysis

TOWARDS A PHILOLOGICAL METRIC THROUGH A TOPOLOGICAL DATA ANALYSIS APPROACH Eduardo Paluzo-Hidalgo Rocio Gonzalez-Diaz Department of Applied Mathematics I Department of Applied Mathematics I School of Computer Engineering School of Computer Engineering University of Seville University of Seville Seville, Spain Seville, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Miguel A. Gutiérrez-Naranjo Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence School of Computer Engineering University of Seville Seville, Spain [email protected] January 14, 2020 ABSTRACT The canon of the baroque Spanish literature has been thoroughly studied with philological techniques. The major representatives of the poetry of this epoch are Francisco de Quevedo and Luis de Góngora y Argote. They are commonly classified by the literary experts in two different streams: Quevedo belongs to the Conceptismo and Góngora to the Culteranismo. Besides, traditionally, even if Quevedo is considered the most representative of the Conceptismo, Lope de Vega is also considered to be, at least, closely related to this literary trend. In this paper, we use Topological Data Analysis techniques to provide a first approach to a metric distance between the literary style of these poets. As a consequence, we reach results that are under the literary experts’ criteria, locating the literary style of Lope de Vega, closer to the one of Quevedo than to the one of Góngora. Keywords Philological metric · Spanish Golden Age Poets · Word embedding · Topological data analysis · Spanish literature arXiv:1912.09253v3 [cs.CL] 11 Jan 2020 1 Introduction Topology is the branch of Mathematics which deals with proximity relations and continuous deformations in abstract spaces. -

Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía De La Edad De Oro, II

Juan Manuel Rozas Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía de la Edad de Oro, II 2003 - Reservados todos los derechos Permitido el uso sin fines comerciales Juan Manuel Rozas Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía de la Edad de Oro, II Las alteraciones estéticas han sido tan notables desde el Renacimiento hasta nuestros días, que un antólogo que quisiera seleccionar un florilegio de poemas del Siglo de Oro que contase, con cierta aproximación, con el asenso de la crítica de las cuatro últimas centurias se vería ante un imposible. Unos poemas son vitales para el Parnaso español de Sedano; otros, distintos, imprescindibles para Las cien mejores poesías de Menéndez Pelayo; otros, incluso de opuesta estilística, para la Primavera y flor de Dámaso Alonso y, naturalmente, otro fue el gusto de Pedro de Espinosa en sus Flores de poetas ilustres, publicadas en 1605. Un caso límite de esas alternancias del gusto nos lo muestran dos genios del barroco: un poeta, Góngora, y un pintor, el Greco. Ambos han pasado por una larga curva de máximos y mínimos. Han ido, desde la indiferencia hasta la cumbre de la cotización universal, pasando por la benevolente explicación de que estuvieron locos. Hoy, y desde hace unos treinta o cuarenta años, de forma continua, la crítica ha remansado sus valoraciones, y estima que son seis los poetas de rango universal que hay en el Siglo de Oro. Tres en el Renacimiento: Garcilaso de la Vega, fray Luis de León y San Juan de la Cruz; tres en el barroco: Luis de Góngora, Lope de Vega y Francisco de Quevedo. -

Two Spanish Rivers in Lope De Vega's Sonnets

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Languages Faculty Publications Foreign Languages and Cultures 2009 Emotion, Satire, and a Sense of Place: Two Spanish Rivers in Lope de Vega’s Sonnets Mark J. Mascia Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/lang_fac Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mascia, Mark J. “Emotion, Satire, and a Sense of Place: Two Spanish Rivers in Lope de Vega’s Sonnets.” Romance Notes 49.3 (2009): 267-276. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Foreign Languages and Cultures at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY EMOTION, SATIRE, AND A SENSE OF PLACE: TWO SPANISH RIVERS IN LOPE DE VEGA’S SONNETS MARK J. MASCIA YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY IN the criticism on the poetry of Lope de Vega (1562-1635), relatively little formal study exists on the use of certain topographical elements found frequently in his work. Whereas scholarship has tended to focus on themes such as love, absence, and spirituality, especially with respect to his sonnets, less attention has been given to related geographical ele- ments which are often intertwined with some of these same themes. One such element is Lope’s use of rivers. The purpose of this study is to examine the ways in which Lope makes use of certain Spanish rivers throughout two very divergent periods in his sonnet writing, and to show the development of how he uses these same rivers with respect to his overall sonnet development. -

High-Fidelity-1982-0

New Home Audio -Video Systems That Do It AM EMBER 19& $1.50 J ICD 06398 THE MAGAZINE OF AUDIO, VIDEC. CLASSICAL MUSIC, AND POPULAF MUST How to Put Pizzazz into Your Car Stereo System Special Pullout -900 New Records from A toZ! The Big Switch to Prerecorded CassettesDoom for LPs? 983 NEW PRODUCT ROUNDUP Hundreds of Exciting New Tape Decks, Speakers, Video Recorders and Cameras, Receivers, Turntables, and More! PLUS Lab Tests on 6 New Stereo Components First VCR from Sansui 08398 .11111IIMIsr-W-WCZNIPM...0 11=111.0=1.-611MC..1k_as. 4C_Isr SAA90High SUPER AVILYN CASSE i Position OITDK Hph Ellas XlissE0 SA -X90 HIGH RESOLUTION Laboratory Standard Cassette Mechanism movimmunnsiniagininniammosi Stevie's cassette is SA -X for all the keys he plays in. f nqvanw When it comes to music, in high bias record- Froespe...111K *Ns Nam levels without distor- Stevie Wonder and TDK ing with sound per- tion or saturation. are perfectionists. Stevie's formance which 00.111.0.1 Last, but not least, perfection lies in his talent. approaches that of TDK's Laboratory TDK's perfection is in its high-energy metal. Standard Mechanism technology. The kind of The exclusive TDK gives Stevie unsur- technology that makes our double -coating of Atpassed cassette re- newly reformulated SA -X Super Avilyn I Witt liability, for a lifetime. high bias cassette the particles 1-tipcmi=uni TDK SA-X-it's .. 2OR cassette that Stevie provides . the machine for Stevie depends on to cap- optimum perform- Wonder's machine. Shouldn't it ture every note and r ancefor each fre- be the machine for yours? nuance of every / quency range. -

Department of Music Programs 1998 - 1999 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 1999 Department of Music Programs 1998 - 1999 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1998 - 1999" (1999). School of Music: Performance Programs. 32. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/32 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Music Music Programs 199 8 -9 9 Olivet Nazarene University Kankakee, Illinois 60901 (815) 939-5110 Olivet Nazarene University Department of Music presents Faculty Recital Mr. Norman Ruiz, classical guitarist 7:30 p.m..Tuesday, September 8, Kresge Auditorium Three Pavatias Luis Milan Fantasia Elegiaca Op. 59 Fernando Sor Three Pieces Isaac Albeniz Mallorca Rumores de la Caleta Leyenda Recuerdos De La Alhambra Francisco Tarrega Danza Espaflola Enrique Granados Prelude in e minor Heitor Villa-Lobos Variations on Sakura Yoquijiro Yocoh Classical guitarist Norman Ruiz is no stranger to Chicago audiences*a frequent performer in the Chicago Symphony’s k\\ chamber m usio$pes, performing in Schoenberg’s Serenade in 1992, \ # . and Berios’ .Se^uJNroj^in 1997. Ruiz also appeared as a soloist with the Chicago SymptWw performing the “Canario” movement of Rodrigo’s Fantasy% m Gentleman in 1991 as part o f their W 'S , Promenade Concert Seri^dn.addilion, he has performed with many f ijpt-. -

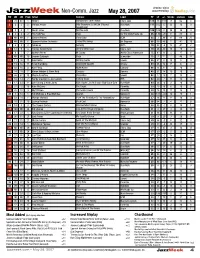

Jazzweek Non-Comm

airplay data JazzWeek Non-Comm. Jazz May 28, 2007 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 73 81 1 Hiromi Sonicbloom/Time Control Telarc Jazz 123 13 110 9 65 3 2 6 5 2 Various Artists Billy Strayhorn: Lush Life [Original Blue Note 111 105 6 23 16 0 Soundtrack] 3 5 4 1 Norah Jones Not Too Late Blue Note 106 106 0 26 28 0 4 3 2 2 The Bad Plus Prog Do The Math/Heads Up 95 120 -25 6 55 4 5 NR NR 5 Stefano Bollani Piano Solo ECM 88 2 86 6 66 37 6 NR NR 6 Spanish Harlem Orchestra United We Swing Six Degrees 86 38 48 1 41 19 7 8 8 3 Antibalas Security ANTI- 79 83 -4 14 41 3 8 13 9 8 Tierney Sutton Band On The Other Side Telarc Jazz 79 46 33 16 20 2 9 9 7 7 Ibrahim Ferrer Mi Sueno World Circuit/Nonesuch 75 62 13 4 27 6 10 NR NR 10 Jerome Sabbagh Pogo Sunnyside 75 3 72 2 48 11 11 11 26 11 Bob DeVos Shifting Sands Savant 55 47 8 15 5 0 12 19 18 11 Brian Bromberg Downright Upright Artistry 49 35 14 17 6 0 13 68 16 8 Kurt Elling Nightmoves Concord 46 14 32 7 28 2 14 24 24 7 Kieran Hebden & Steve Reid Tongues Domino 45 31 14 10 20 0 15 40 67 15 Wayne Escoffery Veneration Savant 42 22 20 7 15 3 16 16 14 2 Randy Crawford & Joe Sample Feeling Good PRA 42 40 2 11 14 0 17 12 44 12 Joe Lovano & Hank Jones Kids: Duets Live At Dizzy‘s Club Coca-Cola Blue Note 40 46 -6 3 28 14 18 37 25 16 Kate McGarry The Target Palmetto 39 23 16 6 26 6 19 35 15 9 Matt Wilson The Scenic Route Palmetto 39 24 15 17 14 1 20 1 13 1 Pat Metheny & Brad Mehldau Quartet Nonesuch 38 131 -93 10 25 1 21 59 29 1 Wynton Marsalis From The Plantation