MONSTROSITY and IDENTITY in the COMEDIAS of LOPE DE VEGA Sarah Apffel Cegelski a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty at the Un

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Proceedings

Book of Proceedings AIESEP 2011 International Conference 22-25 June 2011 University of Limerick, Ireland Moving People, Moving Forward 1 INTRODUCTION We are delighted to present the Book of Proceedings that is the result of an open call for submitted papers related to the work delegates presented at the AIESEP 2011 International Conference at the University of Limerick, Ireland on 22-25 June, 2011. The main theme of the conference Moving People, People Moving focused on sharing contemporary theory and discussing cutting edge research, national and international policies and best practices around motivating people to engage in school physical education and in healthy lifestyles beyond school and into adulthood and understanding how to sustain engagement over time. Five sub-themes contributed to the main theme and ran throughout the conference programme, (i) Educating Professionals who Promote Physical Education, Sport and Physical Activity, (ii) Impact of Physical Education, Sport &Physical Activity on the Individual and Society, (iii) Engaging Diverse Populations in Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sport, (iv) Physical Activity & Health Policies: Implementation and Implications within and beyond School and (v) Technologies in support of Physical Education, Sport and Physical Activity. The papers presented in the proceedings are not grouped by themes but rather by the order they were presented in the conference programme. The number that precedes each title matches the number on the conference programme. We would like to sincerely thank all those who took the time to complie and submit a paper. Two further outlets of work related to the AIESEP 2011 International Conference are due out in 2012. -

The Straits of Magellan Were the Final Piece in in Paris

Capítulo 1 A PASSAGE TO THE WORLD The Strait of Magellan during the Age of its Discovery Mauricio ONETTO PAVEZ 2 3 Mauricio Onetto Paves graduated in 2020 will be the 500th anniversary of the expedition led by history from the Pontifical Catholic Ferdinand Magellan that traversed the sea passage that now carries his University of Chile. He obtained name. It was an adventure that became part of the first circumnavigation his Masters and PhD in History and of the world. Civilizations from the L’École des Ever since, the way we think about and see the world – and even the Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales universe – has changed. The Straits of Magellan were the final piece in in Paris. a puzzle that was yet to be completed, and whose resolution enabled a He is the director of the international series of global processes to evolve, such as the movement of people, academic network GEOPAM the establishment of commercial routes, and the modernization of (Geopolítica Americana de los siglos science, among other things. This book offers a new perspective XVI-XVII), which focuses on the for the anniversary by means of an updated review of the key event, geopolitics of the Americas between based on original scientific research into some of the consequences of the 16th and 17th centuries. His negotiating the Straits for the first time. The focus is to concentrate research is funded by Chile’s National on the geopolitical impact, taking into consideration the diverse scales Fund for Scientific and Technological involved: namely the global scale of the world, the continental scale Development (FONDECYT), and he of the Americas, and the local context of Chile. -

El Concepto De Belleza En Las Rimas Y Rimas Sacras De Lope De Vega Miriam Montoya the University of Arizona

El concepto de belleza en las Rimas y Rimas Sacras de Lope de Vega Miriam Montoya The University of Arizona studiar a Lope de Vega implica hacer un breve recorrido sobre su vida debido a que en ésta se inspiró para escribir muchas de sus obras. En Eeste ensayo se hará un recuento de los sucesos históricos más sobresalientes del tiempo en que vivió este prolífico escritor. También se discutirán los aspectos más importantes de la época literaria y finalmente se hablará sobre el estilo de la poesía lírica de Lope para destacar varios aspectos que permitan entender el concepto de belleza en algunos poemas de sus obras Rimas (1602) y Rimas Sacras (1614). De acuerdo al estudio de Fernando Lázaro Carreter, Lope Félix de Vega Carpio nació en Madrid el 25 de noviembre de 1562. Sus padres, Félix de Vega Carpio y Francisca Fernández Flores eran procedentes de la Montaña y habían llegado a Madrid poco antes del nacimiento de Lope. Félix de Vega era un bordador de renombre que murió cuando Lope tenía quince años. De su madre sólo sabemos que vivió hasta 1589. Acerca de su niñez se sabe que entendía el latín a los cinco años. Además, fue estudiante de un colegio de la Compañía de Jesús donde en tan sólo dos años, dominó la Gramática y la Retórica. Sobre sus estudios universitarios, se cree que estuvo matriculado en la Universidad de Alcalá de 1577 a 1582 y quizás también en la de Salamanca. En el año de 1583, cuando tenía veintiún años, formó parte de la expedición a las Islas Azores para conquistar la última de éstas: La Terceira. -

Ercilla Artículo

Anuario de Pregrado 2004 El discurso de las armas y las letras en La Araucana de Alonso de Ercilla. El discurso de las armas y las letras en La Araucana de Alonso de Ercilla. Rodrigo Faúndez Carreño* La mayor parte de los análisis críticos de que ha sido objeto La Araucana1 desde la publicación de su primera parte en 1569, se han desarrollado a partir de una visión parcial de ella. Los críticos literarios en el curso de los siglos han elogiado o vituperado sus méritos épicos a partir de una concepción aristotélica del género2 lo que ha tenido como consecuencia considerar tradicionalmente a la obra como un poema menor y defectuoso debido a que carece de un protagonista central, participa el autor en el relato y se introducen una serie de pasajes amorosos y bélicos ajenos al curso inicial de la narración: la guerra entre españoles y araucanos. Por su parte la crítica histórica se ha centrado en develar los perjuicios que cumple la introducción de elementos poéticos que invisten bajo atributos de héroes clásicos los rasgos y caracteres indígenas.3 Ante estas concepciones parciales propongo un estudio interdisciplinario que analiza los elementos literarios inmanentes de La Araucana desde una perspectiva historicista que rescata su diálogo (poético) con el medio social que condiciona el sentido de su discurso.4 Estas *Licenciado en Historia Universidad de Chile, abril del 2005. 1 Para el presente trabajo empleo la edición de La Araucana hecha por Isaísas Lerner, publicada en Madrid por la editorial Cátedra en 1999. En adelante se cita según esta edición. -

De Caupolicán a Rubén Darío

Miguel Ángel Auladell Pérez Profesor titular E.U. de literatura española de la Universidad de Ali- cante. Su actividad docente e in- vestigadora se ha centrado princi- palmente en la literatura española del siglo XVII y de la época de Fin de Siglo. Ha formado parte de va- rios proyectos de investigación, tanto de financiación pública como privada. Ha participado en nume- rosos congresos nacionales e inter- nacionales de su especialidad y ha DE CAUPOLICÁN A RUBÉN DARÍO publicado artículos sobre diversos MIGUEL ÁNGEL AULADELL PÉREZ escritores barrocos (Liñán y Verdu- go, Lope de Vega, Ruiz de Alarcón, Calderón) y finiseculares (Rubén Darío, Azorín). Es autor de la mo- nografía titulada La 'Guía y avisos de forasteros que vienen a la Cor te ' del Ldo. Antonio Liñán y Verdu go en su contexto literario y editor Rubén Darío publicó su conocido «Cau- Se ha repetido hasta la saciedad que Rubén del Ensayo bio-bibliográfico de es critores de Alicante y su provincia policán» en el diario santiaguino La Época el habría introducido nuevos textos en^lz^L. pa- de Manuel Rico García. Asimismo, 11 de noviembre de 1888. Bajo el título de «El ra tratar de paliar en lo posible la acusación de ha editado una Antología de poesía y prosa de Rubén Darío. Actual- Toqui», venía acompañado de otros dos sone- «galicismo mental» que le había propinado mente, dirige la edición digital de tos, «Chinampa» y «El sueño del Inca», agru- Juan Valera en dos de sus Cartas americanas di- la obra de Lope de Vega en la Bi- blioteca Virtual Cervantes. -

Translating Rubén Darío's Azul…

Translating Rubén Darío’s Azul… A Purpose and a Method Adam Michael Karr Chesapeake, Virginia B.S. International History, United States Military Academy at West Point, 2005 A thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for a Degree of Master of Arts English Department University of Virginia May, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Thesis Text……….3-47 References………..48-50 Appendix A: “Stories in Prose”………51-88 Appendix B: “The Lyric Year”……….89-116 2 George Umphrey opens the preface of his 1928 edited assortment of Rubén Darío’s prose and poetry with the familiar type of panegyric that begins much of the dissemination and exegesis of Darío’s work – “No apology is needed for [this] publication…he is one of the great poets of all time.” To Umphrey it was nothing more than a quip and a convenient opening statement. Darío had passed away just 12 years earlier but his posterity was assured. The Nicaraguan modernista poet has inspired an entire academic and publishing industry in Spanish language literature that is analogous to Milton or Dickens in English.1 He has had every possible commendation lavished on his legacy, is credited with revolutionizing the Spanish language, dragging it out of two centuries of doldrums following the glorious “Golden Age” of Cervantes and Lope de Vega, and creating the ethos and the identity for an independent Spanish America that would later inspire Borges, Neruda, and García-Márquez. Umphrey had no reason to doubt that any reproduction and exploration of Darío’s work, regardless of language, would be self- justifying, but he unwittingly makes assumptions about the future of language study in universities, priorities and structure in literature departments, the publishing industry and commercial audience, and a myriad of other contextual factors that would complicate Darío’s legacy. -

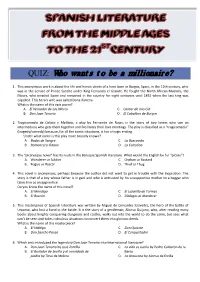

QUIZ: Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

QUIZ: Who wants to be a millionaire? 1. This anonymous work is about the life and heroic deeds of a hero born in Burgos, Spain, in the 11th century, who was in the service of Prince Sancho under King Fernando el Grande. He fought the North African Muslims, the Moors, who invaded Spain and remained in the country for eight centuries until 1492 when the last king was expelled. This hero's wife was called Dona Ximena. What is the name of this epic poem? A. El Vencedor de Los Moros C. Cantar de mio Cid B. Don Juan Tenorio D. El Caballero de Burgos 2. Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea, a play by Fernando de Rojas, is the story of two lovers who use an intermediary who gets them together and facilitates their love meetings. The play is classified as a "tragicomedia" (tragedy/comedy) because, for all the comic situations, it has a tragic ending. Under what name is this play more broadly known? A. Bodas de Sangre C. La Buscavida B. Romancero Gitano D. La Celestina 3. The “picaresque novel” has its roots in the Baroque Spanish literature. What would the English be for “pícaro”? A. Wanderer or Soldier C. Orphan or Bastard B. Rogue or Rascal D. Thief or Thug 4. This novel is anonymous, perhaps because the author did not want to get in trouble with the Inquisition. The story is that of a boy whose father is in gaol and who is entrusted by his unsupportive mother to a beggar who takes him as an apprentice. -

Towards a Philological Metric Through a Topological Data Analysis

TOWARDS A PHILOLOGICAL METRIC THROUGH A TOPOLOGICAL DATA ANALYSIS APPROACH Eduardo Paluzo-Hidalgo Rocio Gonzalez-Diaz Department of Applied Mathematics I Department of Applied Mathematics I School of Computer Engineering School of Computer Engineering University of Seville University of Seville Seville, Spain Seville, Spain [email protected] [email protected] Miguel A. Gutiérrez-Naranjo Department of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence School of Computer Engineering University of Seville Seville, Spain [email protected] January 14, 2020 ABSTRACT The canon of the baroque Spanish literature has been thoroughly studied with philological techniques. The major representatives of the poetry of this epoch are Francisco de Quevedo and Luis de Góngora y Argote. They are commonly classified by the literary experts in two different streams: Quevedo belongs to the Conceptismo and Góngora to the Culteranismo. Besides, traditionally, even if Quevedo is considered the most representative of the Conceptismo, Lope de Vega is also considered to be, at least, closely related to this literary trend. In this paper, we use Topological Data Analysis techniques to provide a first approach to a metric distance between the literary style of these poets. As a consequence, we reach results that are under the literary experts’ criteria, locating the literary style of Lope de Vega, closer to the one of Quevedo than to the one of Góngora. Keywords Philological metric · Spanish Golden Age Poets · Word embedding · Topological data analysis · Spanish literature arXiv:1912.09253v3 [cs.CL] 11 Jan 2020 1 Introduction Topology is the branch of Mathematics which deals with proximity relations and continuous deformations in abstract spaces. -

Downloaded License

Journal of early modern history (2021) 1-36 brill.com/jemh Lepanto in the Americas: Global Storytelling and Mediterranean History Stefan Hanß | ORCID: 0000-0002-7597-6599 The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK [email protected] Abstract This paper reveals the voices, logics, and consequences of sixteenth-century American storytelling about the Battle of Lepanto; an approach that decenters our perspective on the history of that battle. Central and South American storytelling about Lepanto, I argue, should prompt a reconsideration of historians’ Mediterranean-centered sto- rytelling about Lepanto—the event—by studying the social dynamics of its event- making in light of early modern global connections. Studying the circulation of news, the symbolic power of festivities, indigenous responses to Lepanto, and the autobi- ographical storytelling of global protagonists participating at that battle, this paper reveals how storytelling about Lepanto burgeoned in the Spanish overseas territories. Keywords Battle of Lepanto – connected histories – production of history – global history – Mediterranean – Ottoman Empire – Spanish Empire – storytelling Connecting Lepanto On October 7, 1571, an allied Spanish, Papal, and Venetian fleet—supported by several smaller Catholic principalities and military entrepreneurs—achieved a major victory over the Ottoman navy in the Ionian Sea. Between four hundred and five hundred galleys and up to 140,000 people were involved in one of the largest naval battles in history, fighting each other on the west coast of Greece.1 1 Alessandro Barbero, Lepanto: la battaglia dei tre imperi, 3rd ed. (Rome, 2010), 623-634; Hugh Bicheno, Crescent and Cross: the Battle of Lepanto 1571 (London, 2003), 300-318; Peter Pierson, © Stefan Hanss, 2021 | doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10039 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

The Triumphs of Alexander Farnese: a Contextual Analysis of the Series of Paintings in Santiago, Chile

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The Triumphs of Alexander Farnese: A Contextual Analysis of the Series of Paintings in Santiago, Chile Michael J. Panbehchi Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3628 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Michael John Panbehchi 2014 All Rights Reserved The Triumphs of Alexander Farnese: A Contextual Analysis of the Series of Paintings in Santiago, Chile A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Michael John Panbehchi B.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1988 B.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 1994 M.A., New Mexico State University, 1996 Director: Michael Schreffler, Associate Professor, Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia November, 2014 ii Acknowledgment The author wishes to thank several people. I would like to thank my parents for their continual support. I would also like to thank my son José and my wife Lulú for their love and encouragement. More importantly, I would like to thank my wife for her comments on the drafts of this dissertation as well as her help with a number of the translations. -

Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía De La Edad De Oro, II

Juan Manuel Rozas Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía de la Edad de Oro, II 2003 - Reservados todos los derechos Permitido el uso sin fines comerciales Juan Manuel Rozas Góngora, Lope, Quevedo. Poesía de la Edad de Oro, II Las alteraciones estéticas han sido tan notables desde el Renacimiento hasta nuestros días, que un antólogo que quisiera seleccionar un florilegio de poemas del Siglo de Oro que contase, con cierta aproximación, con el asenso de la crítica de las cuatro últimas centurias se vería ante un imposible. Unos poemas son vitales para el Parnaso español de Sedano; otros, distintos, imprescindibles para Las cien mejores poesías de Menéndez Pelayo; otros, incluso de opuesta estilística, para la Primavera y flor de Dámaso Alonso y, naturalmente, otro fue el gusto de Pedro de Espinosa en sus Flores de poetas ilustres, publicadas en 1605. Un caso límite de esas alternancias del gusto nos lo muestran dos genios del barroco: un poeta, Góngora, y un pintor, el Greco. Ambos han pasado por una larga curva de máximos y mínimos. Han ido, desde la indiferencia hasta la cumbre de la cotización universal, pasando por la benevolente explicación de que estuvieron locos. Hoy, y desde hace unos treinta o cuarenta años, de forma continua, la crítica ha remansado sus valoraciones, y estima que son seis los poetas de rango universal que hay en el Siglo de Oro. Tres en el Renacimiento: Garcilaso de la Vega, fray Luis de León y San Juan de la Cruz; tres en el barroco: Luis de Góngora, Lope de Vega y Francisco de Quevedo. -

“Un Episodio Trágico En La Araucana: La Traición De Andresillo (Cantos XXX-XXXII)” Mercedes Blanco, Sorbonne Université

“Un episodio trágico en La Araucana: la traición de Andresillo (cantos XXX-XXXII)” Mercedes Blanco, Sorbonne Université Se han comentado a menudo las diferencias de estructura y planteamiento entre las tres partes que componen La Araucana; la segunda, que contiene episodios proféticos y se desplaza a escenarios distantes de Chile, es distinta de la primera, más lineal y en apariencia más similar a una crónica. La tercera es más breve que las dos primeras, y contiene líneas argumentales muy distintas: final sin final de la guerra en Chile, exploración de Ercilla a zonas desconocidas muy al sur del teatro de la guerra, asunto de la incorporación de Portugal a la corona hispánica. Todo lo cual contribuye a alimentar la impresión de un texto abierto, que se va haciendo a lo largo de veinte años y evoluciona al tiempo que lo hace su creador y al compás del cambio histórico y de las novedades en el campo cultural y literario. De hecho, la tonalidad y los efectos estéticos también varían entre las tres partes, siendo la tercera bastante más sombría que las dos anteriores. De los materiales que la componen puede desgajarse una parte esencial para la lógica narrativa y el efecto del conjunto: el episodio de la traición de Andresillo contado a lo largo de tres cantos. Nos proponemos mostrar que fue estructurado como una tragedia engastada en la epopeya, tal vez por influencia de Aristóteles y de sus comentaristas, episodio cuya concepción y desarrollo deriva de las dos principales tradiciones de las que se nutre la Araucana, la materia caballeresca reflejada en Ariosto y la epopeya clásica.