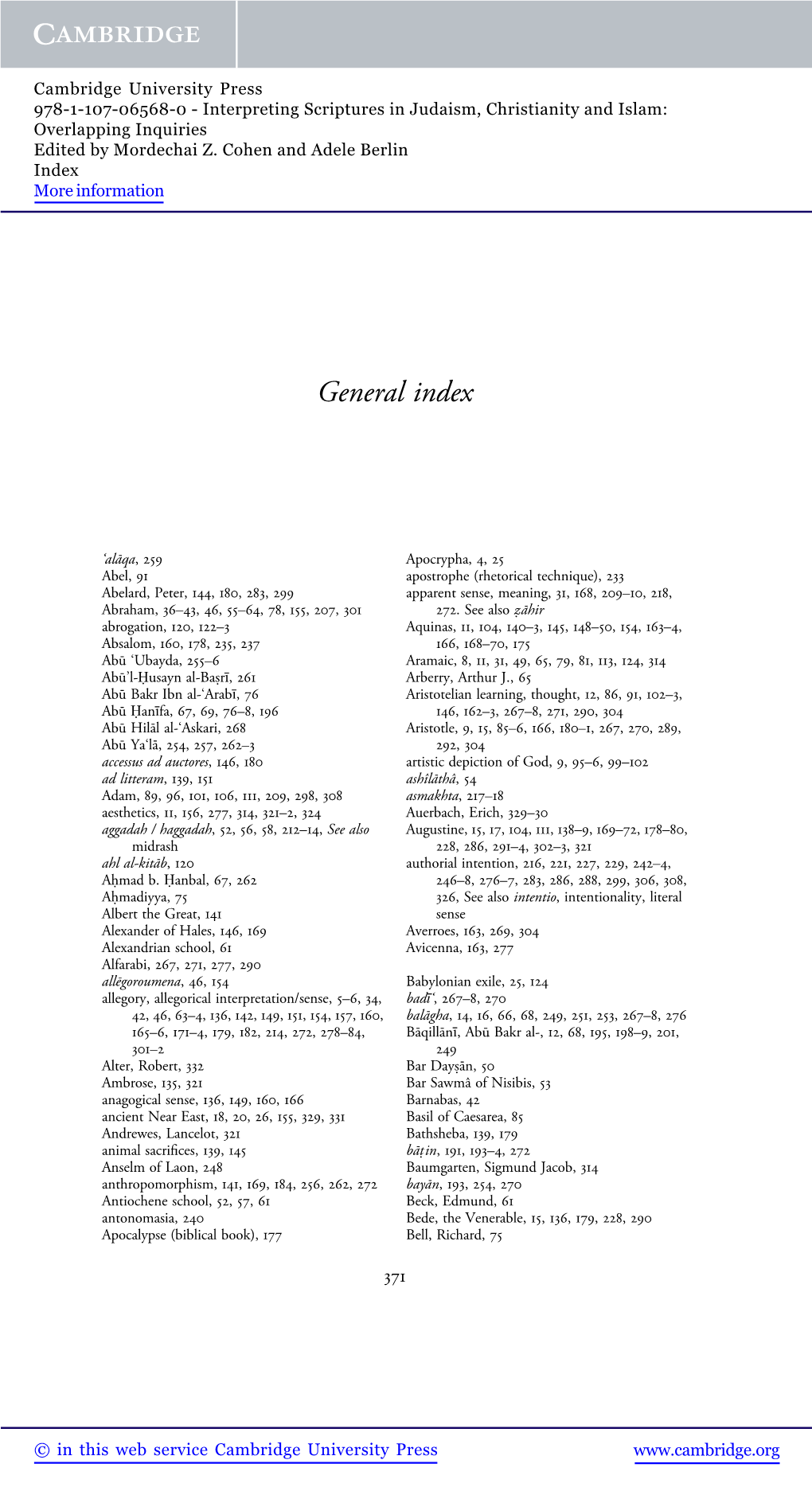

General Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89754-9 - An Introduction to Medieval Theology Rik Van Nieuwenhove Index More information Index Abelard, Peter, 82, 84, 99–111, 116, 120 beatific vision, 41, 62, 191 Alain of Lille, 71 beatitude, 172, 195–96 Albert the Great, 171, 264 Beatrijs van Nazareth, 170 Alexander of Hales, 147, 211, 227 beguine movement, 170 allegory, 15, 43, 45, 47, 177 Benedict XII, Pope, 265 Amaury of Bène, 71 Benedict, St., 28–29, 42 Ambrose, 7, 10, 149 Berengar of Tours, 60, 83, 129, 160, see also amor ipse notitia est 51, 117, see love and knowledge Eucharist anagogy, 47 Bernard of Clairvaux, 79, 82, 100, 104, 110, 112–15, analogy, see univocity 147, 251 analogy in Aquinas, 182–85, 234, 235 critique of Abelard, 110–11 Anselm of Canterbury, 16, 30, 71, 78, 81, 83–98, on loving God, 112–14 204, 236 Boccaccio, Giovanni, 251 Anselm of Laon, 72, 99 Boethius, 29–33, 125, 137 Anthony, St., 27 Bonaventure, 34, 47, 123, 141, 146, 148, 170, 173, apophaticism, 8, 34, 271 176, 179, 211–24, 227, 228, 230, 232, 242, 243, Aquinas, 182–83 245, 254 Aquinas, 22, 24, 34, 47, 51, 72, 87, 89, 90, 133, 146, Boniface, Pope, 249 148, 151, 154, 164, 169, 171–210, 214, 225, 227, 230, 235, 236, 237, 238, 240, 241, 244, 246, Calvin, 14 254, 255, 257, 266 Carabine, Deirdre, 65 Arianism, 20, 21 Carthusians, 79 Aristotle, 9, 20, 29, 78, 84, 179, 181, 192, 195, 212, Cassian, John, 27–29, 47 213, 216, 223, 225, 226, 227, 229, 237, 254, Cassidorius, 124 267, 268 cathedral schools, 82, 169 Arts, 124, 222 Catherine of Siena, 251 and pedagogy (Hugh), 124–28 -

History of the Christian Church*

a Grace Notes course History of the Christian Church VOLUME 5. The Middle Ages, the Papal Theocracy in Conflict with the Secular Power from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII, AD 1049 to 1294 By Philip Schaff CH512 Chapter 12: Scholastic and Mystic Theology History of the Christian Church Volume 5 The Middle Ages, the Papal Theocracy in Conflict with the Secular Power from Gregory VII to Boniface VIII, AD 1049 to 1294 CH512 Table of Contents Chapter 12. Scholastic and Mystic Theology .................................................................................2 5.95. Literature and General Introduction ......................................................................................... 2 5.96. Sources and Development of Scholasticism .............................................................................. 4 5.97. Realism and Nominalism ........................................................................................................... 6 5.98. Anselm of Canterbury ................................................................................................................ 7 5.99. Peter Abelard ........................................................................................................................... 12 5.100. Abelard’s Teachings and Theology ........................................................................................ 18 5.101. Younger Contemporaries of Abelard ..................................................................................... 21 5.102. Peter the Lombard and the Summists -

Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure

The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Davis, Robert. 2012. The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9385627 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Robert Glenn Davis All rights reserved. iii Amy Hollywood Robert Glenn Davis The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure Abstract The image of love as a burning flame is so widespread in the history of Christian literature as to appear inevitable. But as this dissertation explores, the association of amor with fire played a precise and wide-ranging role in Bonaventure’s understanding of the soul’s motive power--its capacity to love and be united with God, especially as that capacity was demonstrated in an exemplary way through the spiritual ascent and death of St. Francis. In drawing out this association, Bonaventure develops a theory of the soul and its capacity for transformation in union with God that gives specificity to the Christian desire for self-abandonment in God and the annihilation of the soul in union with God. Though Bonaventure does not use the language of the soul coming to nothing, he describes a state of ecstasy or excessus mentis that is possible in this life, but which constitutes the death and transformation of the soul in union with God. -

Testing the Prophets BERNARD of SYMEON the NEW IBN TAYMIYYA CLAIRVAUX THEOLOGIAN

Testing the Prophets BERNARD OF SYMEON THE NEW IBN TAYMIYYA CLAIRVAUX THEOLOGIAN ➔ CAMEL MEAT Reason does not suffice without revelation nor does revelation suffice without reason. The one who would urge pure taqlīd and the total rejection of reason is in error and he who would make do with pure reason apart from the lights of the Koran and the Sunna is deluded. If you are in doubt about whether a certain person is a prophet or not, certainty can be had only through knowledge of what he is like, either by personal observation or reports and testimony. If you have an understanding of medicine and jurisprudence, you can recognize jurists and doctors by observing what they are like, and listening to what they had to say, even if you haven’t observed them. So you have no difficulty recognizing that Shāfiʿī was a jurist or Galen a doctor, this being knowledge of what is in fact the case and not a matter of taqlīd shown to another person. Rather, since you know something of jurisprudence and medicine, and you have perused their books and treatises, you have arrived at necessary knowledge about what they are like. Likewise, once you grasp the meaning of prophecy and then investigate the Qurʾān and [ḥadīth] reports extensively, you arrive at necessary knowledge that [Muḥammad] is at the highest degree of prophecy. Thirst for grasping the true natures of things was a habit and practice of mine from early on in my life, an inborn and innate tendency (gharīza wa-fiṭra) given by God in my very nature, not chosen or contrived. -

Logic in the Middle Ages

Logic in the Middle Ages. Peripatetic position: Logic is a preliminary to scientific inquiry. Stoic position: Logic is part of philosophy. In the Middle Ages: Logic as ars sermocinalis. (Part of the preliminary studies of the trivium.) Part II of today’s lecture and next lecture. Logic (in a broader sense) as central to important questions of philosophy, metaphysics and theology. Part I of today’s lecture. Core Logic – 2004/05-1ab – p. 3/28 Theological Questions. Theological questions connected with the set-up of logic. The Immortality of the Soul. The Eucharist. The Trinity and the ontological status of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Free will and responsibility for one’s actions. (Recall the Master argument and its modal rendering as } ' ! '.) Core Logic – 2004/05-1ab – p. 4/28 The Categories. Aristotle, Categories: The ten categories (1b25). Substance When Quality Position Quantity Having Relation Action Where Passion The two ways of predication. essential predication: “Socrates is a human being”; “human IS SAID OF Socrates” accidental predication: “Socrates is wise”; “wisdom IS IN Socrates” Core Logic – 2004/05-1ab – p. 5/28 Essential predication. “essential”: You cannot deny the predicate without changing the meaning of the subject. “animal IS SAID OF human”. “human IS SAID OF Socrates”. IS SAID OF is a transitive relation (reminiscent of Barbara). Related to the category tree: Genus. Animal. ss sss sss yss ² Species. Human. Dog. K rrr KK rr KKK rrr KKK xrr ² ² K% Individual. Socrates. Aristotle. Lassie. Boomer. Core Logic – 2004/05-1ab – p. 6/28 Substances. NOT IN IN SAID OF Universal substances Universal accidents human, animal wisdom NOT SAID OF Particular substances Particular accidents Socrates, Aristotle Plato ("). -

David Luscombe: Publications

David Luscombe: Publications 1963 Review: David Knowles, Great Historical Enterprises. Problems in Monastic History (London, 1963), in The Cambridge Review, 85/2064, November 30, 169-71 Review: M. Wilks, The Problem of Sovereignty in the Later Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1963), in Theology 66, 341 1964 Review: Jean Décarreaux, Monks and Civilisation (London, 1964), in Theology 67, 464-6 1965 “Towards a new edition of Peter Abelard's Ethica or Scito te ipsum: an introduction to the manuscripts,” Vivarium 3, 115-27 Review: Donald Nicholl, Thurstan, Archbishop of York (1114-1140) (York, 1964), in New Blackfriars 46, 257-8 Review: G. Constable, Monastic Tithes from their Origins to the Twelfth Century (London, 1964), in New Blackfriars 46, 486 Review: Studies in Church History, 1, eds. C.W. Dugmore and C. Duggan (London, 1964) and The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, ed. C.H. Lawrence (London, 1965), in New Blackfriars 47, 48 1966 “Berengar, Defender of Peter Abelard,” Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale 33, 319-37 “Anselm of Laon,” Colliers Encyclopedia, 1 “Nature in the Thought of Peter Abelard,” La Filosofia della Natura nel Medioevo. Atti del Terzo Congresso Internazionale di Filosofia Medioevale (Milan), 314-19 Review: Dom Adrian Morey and C.N.L. Brooke, Gilbert Foliot and his Letters (Cambridge, 1965), in New Blackfriars 47, 612 Review: B. Pullan, Sources for the History of Medieval Europe from the Mid-Eighth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century (Oxford, 1966), in The Cambridge Review, 29 October 1966, 73 1967 “Bernard of Chartres,” in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. P. -

Anselm of Canterbury and the Development of Theological Thought, C

Durham E-Theses Anselm of Canterbury and the Development of Theological Thought, c. 1070-1141 DUNTHORNE, JUDITH,RACHEL How to cite: DUNTHORNE, JUDITH,RACHEL (2012) Anselm of Canterbury and the Development of Theological Thought, c. 1070-1141, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6360/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Anselm of Canterbury and the Development of Theological Thought, c. 1070-1141 Judith R. Dunthorne Abstract This thesis explores the role of Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) in the development of theological thought in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. It aims to demonstrate that Anselm’s thought had a greater impact on the early development of scholastic theology than is often recognized, particularly in the areas of the doctrine of the incarnation and redemption, but also in his discussion of freedom and sin. -

A Scholastic Miscellany General Editors

A Scholastic Miscellany General Editors John Bafflie (1886-1960) served as President of the World Council of Churches, a member of the British Council of Churches, Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, and Dean of the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Edinburgh. John T. McNeill (1885-1975) was Professor of the History of European Christianity at the University of Chicago and then Auburn Professor of Church History at Union Theological Seminary in New York. Henry P. Van Dusen (1897-1975) was an early and influen- tial member of the World Council of Churches and served at Union Theological Seminary in New York as Roosevelt Professor of Systematic Theology and later as President. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS A Scholastic Miscellany Anselm to Ockham Edited and translated by EUGENE R. FAIR WEATHER MA, BD, ThD © 1956 The Westminster Press Paperback reissued 2006 by Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, Kentucky. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For informa- tion, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202-1396. Cover design by designpointinc. com Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standards Institute Z39.48 standard.® PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA United States Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. -

Medieval Theologians: an Introduction to Theology in the Medieval Period

Mystics, Masters, and Martyrs: Theology and Theologians in Medieval Europe January 2017 9-11:30am, Gardencourt 206 Instructor: Christopher Elwood Course Description: This course will explore the lives, thought, and context of significant Christian figures of the Middle Ages in Europe: Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109), Marguerite Porete (d. 1310), and Gregory Palamas (1296- 1359). We will focus on themes of revelation and knowledge of God, attending to how these theologians and spiritual authors integrated practice and belief, spirituality, and theology. In addition, students will have the opportunity to research another medieval theologian of their choice. Goals and Objectives: The goal of the course is to help students develop their capacity for faithful and coherent theological expression in pastoral practice. Students will • gain a basic understanding of the different forms of theology and spirituality developed and practiced in Europe in the Middle Ages, • sharpen their skills of theological interpretation through the close reading and discussion of primary sources, orally and in writing, • develop their ability to make responsible and relevant use of historic theological writing, • reflect on various models for integrating the analytical, devotional and practical components of theology and spiritual writing, • and clarify their own theological and ethical positions. Required Books: Anselm of Canterbury: The Major Works. Eds. Brian Davis and G.R. Evans. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. (Referred to in the syllabus as AoC) Marguerite Porete: The Mirror of Simple Souls. Ed. Ellen L. Babinsky. The Classics of Western Spirituality. New York: Paulist Press, 1993. Gregory Palamas: The Triads. Eds. -

Aquinas and “Alcuin”: a New Source of the Catena Aurea on John

AQUINAS AND “ALCUIN”: A NEW SOURCE OF THE CATENA AUREA ON JOHN Alexander ANDRÉE, Tristan SHARP, and Richard SHAW Abstract In the Catena aurea Thomas Aquinas brought together commentary extracted from the works of all the major Fathers on the four Gospels. Unknown to him and to all scholars since, however, his citations from Alcuin in the Catena on John did not in fact come from the Northumbrian’s Commentarius. They derive instead from a commentary on John’s Gospel probably compiled by Anselm of Laon in the early twelfth century. This same text, the Glosae super Iohannem, was also the principal source for the so-called Glossa ordinaria on John. Through both the Glossa and the Catena therefore this intriguing text indi- rectly ensured the continued and widespread influence of Anselm and his teaching throughout the later Middle Ages. The Catena aurea, or Glossa (expositio) continua in Matthaeum, Mar- cum, Lucam, Iohannem, as it was originally known,1 was one of Thomas Aquinas’s most important and popular works. It marked “a turning point in the development of Aquinas’s theology as well as in the history of Catholic dogma.”2 The Catena was also one of the “most widely diffused works of Aquinas, both in manuscript and in print.”3 The very sobriquet, ‘Golden Chain’, which the Glossa con- tinua gained within a century of its composition, is testimony to the 1 Quotations from the Catena will be from: S. Thomae Aquinatis Catena Aurea in quattuor Evangelia, I: Expositio in Matthaeum et Marcum, II: Expositio in Lucam et Ioan- nem, ed. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16367-6 — the Cambridge History of French Thought Edited by Michael Moriarty , Jeremy Jennings Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16367-6 — The Cambridge History of French Thought Edited by Michael Moriarty , Jeremy Jennings Index More Information Index abbeys, 11–12 Anti-Machiavel, 91 Abbo of Fleury, 12 apologetics, 112 Abbey of St. Germaine at Auxerre, 11–12 Apologia Catholica, 94–5 Abelard, Peter, 14–15 Arabic philosophy, 17–18 Abrégé, 119–20 Archaeology of Knowledge, The, 460–1 Académie du Palais, 39 Arendt, Hannah, 353–4, 451 Académie française, 98, 318, 349 Aristotelianism Académie royale de peinture et de and absolute royal power, 94 sculpture, 259 based Catholicism, 44 Acarie, Madame (Marie de l’Incarnation), 142 and Jansenism, 139–40 Adolphe, 319 in medieval French thought adoptianism, 11 and Buridan, 27–8 Aquinas, Thomas fifteenth century, 32 and Catholicism, 44 and Latin Christendom, 20–1 form of the soul, 21 new resources, 19 opposition to Averroism, 21 and Oresme, 28–9 aesthetics, see also arts in medieval Jewish thought, 17–18 defined, 183 and Montaigne, 73–4 during the Enlightenment, 256–62 as moral thought, 55–9 Against Vain Curiosity in Matters of Faith, 31 and the Ramus method, 67–8 Alan of Lille (Universal Doctor), 16 Arnau de Vilanova, 24 Albert the Great, 20 Arnaud, Angélique, 137, 145 Algerian War, 441–3 Arnauld, Antoine, 137, 139–40, 140n, 144, Alleg, Henri, 286, 443 152, 162 Althusser, Louis, 416–23 Aron, Raymond, 381–2, 446–9 Althusser’s Lesson, 422 arts, see also aesthetics altruism, 345–6 and aesthetics, 183–9 Amaury of Bène, 16 Diderot on, 221, 224–5 amour-propre, 172 Voltaire’s commitment to, 216 Animadversiones -

The Twelfth-Century Renaissance Spring 2012, Palmer 205, TR 11:00-12:15

1 History 415-01: The Twelfth-Century Renaissance Spring 2012, Palmer 205, TR 11:00-12:15 Professor Alex Novikoff Office: Buckman 219 Office Hours: TR 2-4 PM, and by appointment Email: [email protected] Course Overview In 1927 the great American medievalist Charles Homer Haskins published his classic work, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. The book was both an assessment of what was a widely-recognized turning point in European history and culture and an appropriation for that period of the recently popularized term “renaissance,” by then conventionally located in the late fourteenth through the late sixteenth centuries. The purpose of this course is fourfold: to look at Haskins’ great book, to consider aspects of the twelfth century that Haskins did not, to reconsider some of those that he did, and to ponder his and others’ use of the term “renaissance” to describe the twelfth century. Thus this seminar will sample the wide range of intellectual, political, institutional, spiritual, and cultural developments that took place in Western Europe between the late eleventh century and the late twelfth century, using primary sources as our guide and supplemented by generous readings from the best recent scholarship. Among the topics we will investigate are the study of the liberal arts in cathedral schools and the first universities; the centralization of political authority in France and England; the spiritual renewal associated with new monastic orders; the music and poetry of the traveling Minstrels that embody the twelfth-century spirit of chivalry and courtly love; and the increasingly fraught relations between Christians and Jews that resulted in part from this intellectual renaissance.