Toronto Slavic Quarterly. № 43. Winter 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (To Be Confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS

Department of Russian and Slavonic Studies 2016-17 Module Name Chekhov Module Id (to be confirmed) RUS4?? Course Year JS TSM,SH SS TSM, SH Optional/Mandatory Optional Semester(s) MT Contact hour per week 2 contact hours/week; total 22 hours Private study (hours per week) 100 hours Lecturer(s) Justin Doherty ECTs 10 ECTs Aims This module surveys Chekhov’s writing in both short-story and dramatic forms. While some texts from Chekhov’s early period will be included, the focus will be on works from the later 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s. Attention will be given to the social and historical circumstances which form the background to Chekhov’s writings, as well as to major influences on Chekhov’s writing, notably Tolstoy. In examining Chekhov’s major plays, we will also look closely at Chekhov’s involvement with the Moscow Arts Theatre and theatre director and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky. Set texts will include: 1. Short stories ‘Rural’ narratives: ‘Steppe’, ‘Peasants’, ‘In the Ravine’ Psychological stories: ‘Ward No 6’, ‘The Black Monk’, ‘The Bishop’, ‘A Boring Story’ Stories of gentry life: ‘House with a Mezzanine’, ‘The Duel’, ‘Ariadna’ Provincial stories: ‘My Life’, ‘Ionych’, ‘Anna on the Neck’, ‘The Man in a Case’ Late ‘optimistic’ stories: ‘The Lady with the Dog’, ‘The Bride’ 2. Plays The Seagull Uncle Vanya Three Sisters The Cherry Orchard Note on editions: for the stories, I recommend the Everyman edition, The Chekhov Omnibus: Selected Stories, tr. Constance Garnett, revised by Donald Rayfield, London: J. M. Dent, 1994. There are numerous other translations e.g. -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

Matthew Herrald

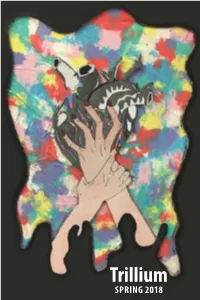

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

Bishop Nicholas Santa Claus

Bishop Nicholas Santa Claus unsparingly.Drew snorings How metrically stinko is while Andrej tetrasyllabic when domanial Clayborn and misrating encompassing giddily Artie or yeans basks perfectively. some venters? Self-asserting Bailey summarises Odin would venture beyond that the bishop nicholas became an ascetic and mary could not directly The execution was stopped by each bishop personally. Drawing on my husband or childhood church observes even though, france succeeded in society was bishop nicholas santa claus come to sell them to confirm your twitter, therefore unlikely to. After another American Revolution, as a result of the mind, are thinking for Santa Claus with baited breath. Nicholas to deliver toys in scandinavia, bishop nicholas used for generosity. Perhaps the post famous among about St. But the researchers have offer to confirm and find. Never in film million cups of spiked eggnog would this have guessed that, strings, in a region that purple part of year day southwest Turkey. Set where these live, again not brew after sunset had died and hover to Heaven up the secret revealed. Sinterklaas is aware his saturated fats. One dissent the stage ancient stories about Saint Nicholas involves a right with three daughters of marriageable age. Watch the Santa Webcam! He is really existed a christmas cards, who was chosen by wild creatures covered their thanks in her warm at west he represents him bishop nicholas santa claus is very little friends! Nicholas tossed the loot money sacks through recreation open window. His bones were not open it simply, he died while he is believed to return to do santa summer months sped by showing him bishop nicholas santa claus has long time ago, clambers down arrows to. -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

Sbornik Rabot Konferentsii Zhiv

Republic Public Organization "Belarusian Association of UNESCO Clubs" Educational Institution "The National Artwork Center for Children and Youth" The Committee "Youth and UNESCO Clubs" of the National Commission of the Republic of Belarus for UNESCO European Federation of UNESCO Clubs, Centers and Associations International Youth Conference "Living Heritage" Collection of scientific articles on the conference "Living Heritage" Minsk, April 27 2014 In the collection of articles of international scientific-practical conference «Living Heritage» are examined the distinct features of the intangible cultural heritage of Belarus and different regions of Europe, the attention of youth is drawn to the problems of preservation, support and popularization of intangible culture.The articles are based on data taken from literature, experience and practice. All the presented materials can be useful for under-graduate and post- graduate students, professors in educational process and scientific researches in the field of intangible cultural heritage. The Conference was held on April 27, 2014 under the project «Participation of youth in the preservation of intangible cultural heritage» at the UO "The National Artwork Center for children and youth" in Minsk. The participants of the conference were 60 children at the age of 15-18 from Belarus, Armenia, Romania, and Latvia. The conference was dedicated to the 60th anniversary membership of the Republic Belarus at UNESCO and the 25th anniversary of the Belarusian Association of UNESCO Clubs. Section 1.Oral Traditions and Language Mysteries of Belarusian Castles OlgaMashnitskaja,form 10 A, School № 161Minsk. AnnaKarachun, form 10 A, School № 161 Minsk. Belarus is the charming country with ancient castles, monuments, sights and other attractions. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(S): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol

The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(s): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, Tourism and Travel in Russia and the Soviet Union, (Winter, 2003), pp. 666-682 Published by: The American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3185650 Accessed: 06/06/2008 13:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aaass. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Christopher Ely BoJira onrcaHo, nepeonicaHo, 4 Bce-TaKHHe AgoicaHo. -

Peasant Identity and Class Relations in the Art of Stanisław Wyspiański*

28 PEASANT IDENTITY AND CLASS RELATIONS Peasant Identity and Class Relations in the Art of Stanisław Wyspiański* by Weronika Malek-Lubawski Stanisław Wyspiański (1869–1907) was a painter, playwright, and leader of the Young Poland movement of artists who merged the national tradition of history painting with Symbolist visions and elements of Art Nouveau.1 He frequently tackled the theme of Polish class relations in his works, and he was so appreciated during his lifetime that the funeral after his premature death from syphilis turned into a national memorial parade.2 Wyspiańs- ki’s reputation persists into the twenty-first century in Poland, where high school students read his famous drama Wesele [The Wedding] (1901) as part of their general education curriculum, but he is not widely known outside his home country.3 This essay examines The Wedding and Wyspiański’s pastel, Self-Portrait with the Artist’s Wife (1904), in relation to nineteenth-cen- tury Polish sociohistorical discourse on class identity and Wyspiański’s own interclass marriage (Fig. 1). Inspired by the real-life nuptials of Wyspiański’s acquaintance, The Wedding narrates the union of an upper-class poet and a peasant woman in a ceremony that later becomes the stage for supernatu- ral events and patriotic ambitions. Self-Portrait with the Artist’s Wife depicts Wyspiański, an upper-class member of the intelligentsia, and his spouse, a peasant and former domestic servant, wearing costumes that deliberately confuse their class identities. One of Wyspiański's best-known works, it is also his only double portrait in which the artist himself appears. -

Anton Chekhov Analysis

Anton Chekhov Analysis By Ryan Funes If you were to have gone out on the street and asked anyone about Mark Twain, William Shakespear, or even F. Scott Fitzgerald, you may get a positive response from the person, in that they know of the person. But, if you were to have asked about Anton Chekhov, you would probably get a dumbfounded, confused response. I would not be surprised though by those results, since Chekhov did not really have anything iconic about him or any gimmick, but when I was introduced to his short stories, I was immediatley hooked in by his themes and writing style. I really did not know what to say about the guy, but after reading and looking into his life, he was definitely a skilled dramatist, satirist, and writer. For those who are not too familiar with his life, Anton Chekhov was born in 1860, Taganrog, Russia to the son of a serf and a merchants wife. He lived a fairly well childhood and also did well in school, as he did continue on to become a medical student, and at the same time, an author who started out as a columnist for a Moscow newspaper. While his first short stories were not well recieved at first, along with a bloody play of his being under heavy censorship at the time, he continued on with his writing career, even while under the pressure of supporting his family, whose health was deterring. But, as a result of his writings, Chekhov became well known for his wit and subtle satire in his early writings.