Evidentiality in Uzbek and Kazakh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Grammatical Gender in Hindukush Languages

Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General linguistics Bachelor's programme in Linguistics Spring term 2016 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examinator: Bernhard Wälchli Expert reviewer: Emil Perder Project affiliation: “Language contact and relatedness in the Hindukush Region,” a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (421-2014-631) Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Abstract In the mountainous area of the Greater Hindukush in northern Pakistan, north-western Afghanistan and Kashmir, some fifty languages from six different genera are spoken. The languages are at the same time innovative and archaic, and are of great interest for areal-typological research. This study investigates grammatical gender in a 12-language sample in the area from an areal-typological perspective. The results show some intriguing features, including unexpected loss of gender, languages that have developed a gender system based on the semantic category of animacy, and languages where this animacy distinction is present parallel to the inherited gender system based on a masculine/feminine distinction found in many Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords Grammatical gender, areal-typology, Hindukush, animacy, nominal categories Grammatiskt genus i Hindukush-språk En areal-typologisk studie Julia Lautin Sammanfattning I den här studien undersöks grammatiskt genus i ett antal språk som talas i ett bergsområde beläget i norra Pakistan, nordvästra Afghanistan och Kashmir. I området, här kallat Greater Hindukush, talas omkring 50 olika språk från sex olika språkfamiljer. Det stora antalet språk tillsammans med den otillgängliga terrängen har gjort att språken är arkaiska i vissa hänseenden och innovativa i andra, vilket gör det till ett intressant område för arealtypologisk forskning. -

A New Classification of the Chuvash-Turkic Languages

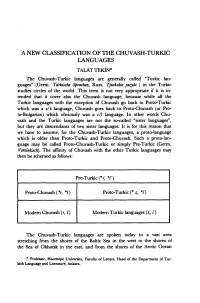

A NEW CLASSİFICATİON OF THE CHUVASH-TURKIC LANGUAGES T A L Â T TEKİN * The Chuvash-Turkic languages are generally called “Turkic lan guages” (Germ. Türkische Sprachen, Russ. Tjurkskie jazyki ) in the Turkic studies circles of the world. This term is not very appropriate if it is in- tended that it cover also the Chuvash language, because while ali the Turkic languages with the exception of Chuvash go back to Proto-Turkic vvhich was a z/s language, Chuvash goes back to Proto-Chuvash (or Pro- to-Bulgarian) vvhich obviously was a r/l language. In other vvords Chu vash and the Turkic languages are not the so-called “sister languages”, but they are descendants of two sister languages. It is for this reason that we have to assume, for the Chuvash-Turkic languages, a proto-language vvhich is older than Proto-Turkic and Proto-Chuvash. Such a proto-lan- guage may be called Proto-Chuvash-Turkic or simply Pre-Turkic (Germ. Vortürkisch). The affinity of Chuvash vvith the other Turkic languages may then be schemed as follovvs: Pre-Turkic i*r, * i ) Proto-Chuvash ( *r, */) Proto-Turkic (* z, *s) Modem Chuvash (r, l) Modem Turkic languages (z, s ) The Chuvash-Turkic languages are spoken today in a vast area stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the vvest to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in the east, and from the shores of the Arctic Ocean * Professor, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Letters, Head of the Department of Tur- kish Language and Literatüre, Ankara. ■30 TALÂT TEKİN in the north to the shores of Persian Gulf in the south. -

Turkic Languages 161

Turkic Languages 161 seriously endangered by the UNESCO red book on See also: Arabic; Armenian; Azerbaijanian; Caucasian endangered languages: Gagauz (Moldovan), Crim- Languages; Endangered Languages; Greek, Modern; ean Tatar, Noghay (Nogai), and West-Siberian Tatar Kurdish; Sign Language: Interpreting; Turkic Languages; . Caucasian: Laz (a few hundred thousand speakers), Turkish. Georgian (30 000 speakers), Abkhaz (10 000 speakers), Chechen-Ingush, Avar, Lak, Lezghian (it is unclear whether this is still spoken) Bibliography . Indo-European: Bulgarian, Domari, Albanian, French (a few thousand speakers each), Ossetian Andrews P A & Benninghaus R (1989). Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert (a few hundred speakers), German (a few dozen Verlag. speakers), Polish (a few dozen speakers), Ukranian Aydın Z (2002). ‘Lozan Antlas¸masında azınlık statu¨ su¨; (it is unclear whether this is still spoken), and Farklı ko¨kenlilere tanınan haklar.’ In Kabog˘lu I˙ O¨ (ed.) these languages designated as seriously endangered Azınlık hakları (Minority rights). (Minority status in the by the UNESCO red book on endangered lan- Treaty of Lausanne; Rights granted to people of different guages: Romani (20 000–30 000 speakers) and Yid- origin). I˙stanbul: Publication of the Human Rights Com- dish (a few dozen speakers) mission of the I˙stanbul Bar. 209–217. Neo-Aramaic (Afroasiatic): Tu¯ ro¯ yo and Su¯ rit (a C¸ag˘aptay S (2002). ‘Otuzlarda Tu¨ rk milliyetc¸ilig˘inde ırk, dil few thousand speakers each) ve etnisite’ (Race, language and ethnicity in the Turkish . Languages spoken by recent immigrants, refugees, nationalism of the thirties). In Bora T (ed.) Milliyetc¸ilik ˙ ˙ and asylum seekers: Afroasiatic languages: (Nationalism). -

Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic Language of Siberia Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov

Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov To cite this version: Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov. Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia. In Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor. Loanwords in the World’s Languages: a Comparative Handbook, de Gruyter Mouton, pp.496-524, 2009. hal-02012602 HAL Id: hal-02012602 https://hal.univ-lyon2.fr/hal-02012602 Submitted on 23 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 19 Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia* Brigitte Pakendorf and Innokentij N. Novgorodov 1. The language and its speakers Sakha (often referred to as Yakut) is a Turkic language spoken in northeastern Siberia. It is classified as a Northeastern Turkic language together with South Sibe- rian Turkic languages such as Tuvan, Altay, and Khakas. This classification, however, is based primarily on geography, rather than shared linguistic innovations (Schönig 1997: 123; Johanson 1998: 82f); thus, !"erbak (1994: 37–42) does not include Sakha amongst the South Siberian Turkic languages, but considers it a separate branch of Turkic. The closest relative of Sakha is Dolgan, spoken to the northwest of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). -

The Finnish Korean Connection: an Initial Analysis

The Finnish Korean Connection: An Initial Analysis J ulian Hadland It has traditionally been accepted in circles of comparative linguistics that Finnish is related to Hungarian, and that Korean is related to Mongolian, Tungus, Turkish and other Turkic languages. N.A. Baskakov, in his research into Altaic languages categorised Finnish as belonging to the Uralic family of languages, and Korean as a member of the Altaic family. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Finnish is closer to Korean than to Hungarian, and that likewise Korean is closer to Finnish than to Turkic languages . In his analytic work, "The Altaic Family of Languages", there is strong evidence to suggest that Mongolian, Turkic and Manchurian are closely related, yet in his illustrative examples he is only able to cite SIX cases where Korean bears any resemblance to these languages, and several of these examples are not well-supported. It was only in 1927 that Korean was incorporated into the Altaic family of languages (E.D. Polivanov) . Moreover, as Baskakov points out, "the Japanese-Korean branch appeared, according to (linguistic) scien tists, as a result of mixing altaic dialects with the neighbouring non-altaic languages". For this reason many researchers exclude Korean and Japanese from the Altaic family. However, the question is, what linguistic group did those "non-altaic" languages belong to? If one is familiar with the migrations of tribes, and even nations in the first five centuries AD, one will know that the Finnish (and Ugric) tribes entered the areas of Eastern Europe across the Siberian plane and the Volga. -

Contact in Siberian Languages Brigitte Pakendorf

Contact in Siberian Languages Brigitte Pakendorf To cite this version: Brigitte Pakendorf. Contact in Siberian Languages. In Raymond Hickey. The Handbook of Language Contact, Blackwell Publishing, pp.714-737, 2010. hal-02012641 HAL Id: hal-02012641 https://hal.univ-lyon2.fr/hal-02012641 Submitted on 16 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 9781405175807_4_035 1/15/10 5:38 PM Page 714 35 Contact and Siberian Languages BRIGITTE PAKENDORF This chapter provides a brief description of contact phenomena in the languages of Siberia, a geographic region which is of considerable significance for the field of contact linguistics. As this overview cannot hope to be exhaustive, the main goal is to sketch the different kinds of language contact situation known for this region. Within this larger scope of contact among the languages spoken in Siberia, a major focus will be on the influence exerted by Evenki, a Northern Tungusic language, on neighboring indigenous languages. The chapter is organized as follows: after a brief introduction to the languages and peoples of Siberia (section 1), the influence exerted on the indigenous languages by Russian, the dominant language in the Russian Federation, is described in section 2. -

The Turkic Languages the Structure of Turkic

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 27 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Turkic Languages Lars Johanson, Éva Á. Csató The Structure of Turkic Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203066102.ch3 Lars Johanson Published online on: 21 May 1998 How to cite :- Lars Johanson. 21 May 1998, The Structure of Turkic from: The Turkic Languages Routledge Accessed on: 27 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203066102.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 The Structure 0/ Turkic Lars lohanson Introduction Throughout their history and in spite of their huge area of distribution, Turkic languages share essential structural features. Many of them are common to Eurasian languages of the Altaic and Uralic types. While often dealt with in typologically oriented linguistic work, most aspects of Turkic structure still call for more unbiased and differentiated description. -

(In)Stability in Hindu Kush Indo-Aryan Languages Henrik Liljegren Stockholm University

Chapter 10 Gender typology and gender (in)stability in Hindu Kush Indo-Aryan languages Henrik Liljegren Stockholm University This paper investigates the phenomenon of gender as it appears in 25 Indo-Aryan languages (sometimes referred to as “Dardic”) spoken in the Hindu Kush-Karako- rum region – the mountainous areas of northeastern Afghanistan, northern Pak- istan and the disputed territory of Kashmir. Looking at each language in terms of the number of genders present, to what extent these are sex-based or non-sex- based, how gender relates to declensional differences, and what systems of assign- ment are applied, we arrive at a micro-typology of gender in Hindu Kush Indo- Aryan, including a characterization of these systems in terms of their general com- plexity. Considering the relatively close genealogical ties, the languages display a number of unexpected and significant differences. While the inherited sex-based gender system is clearly preserved in most of the languages, and perhaps even strengthened in some, it is curiously missing altogether in others (such as in Kalasha and Khowar) or seems to be subject to considerable erosion (e.g. in Dameli). That the languages of the latter kind are all found at the northwestern outskirts ofthe Indo-Aryan world suggests non-trivial interaction with neighbouring languages without gender or with markedly different assignment systems. In terms of com- plexity, the southwestern-most corner of the region stands out; here we find a few languages (primarily belonging to the Pashai group) that combine inherited sex- based gender differentiation with animacy-related distinctions resulting in highly complex agreement patterns. -

Survey of the World's Languages

Survey of the world’s languages The languages of the world can be divided into a number of families of related languages, possibly grouped into larger stocks, plus a residue of isolates, languages that appear not to be genetically related to any other known languages, languages that form one-member families on their own. The number of families, stocks, and isolates is hotly disputed. The disagreements centre around differences of opinion as to what constitutes a family or stock, as well as the acceptable criteria and methods for establishing them. Linguists are sometimes divided into lumpers and splitters according to whether they lump many languages together into large stocks, or divide them into numerous smaller family groups. Merritt Ruhlen is an extreme lumper: in his classification of the world’s languages (1991) he identifies just nineteen language families or stocks, and five isolates. More towards the splitting end is Ethnologue, the 18th edition of which identifies some 141 top-level genetic groupings. In addition, it distinguishes 1 constructed language, 88 creoles, 137 or 138 deaf sign languages (the figures differ in different places, and this category actually includes alternate sign languages — see also website for Chapter 12), 75 language isolates, 21 mixed languages, 13 pidgins, and 51 unclassified languages. Even so, in terms of what has actually been established by application of the comparative method, the Ethnologue system is wildly lumping! Some families, for instance Austronesian and Indo-European, are well established, and few serious doubts exist as to their genetic unity. Others are quite contentious. Both Ruhlen (1991) and Ethnologue identify an Australian family, although there is as yet no firm evidence that the languages of the continent are all genetically related. -

Fusion, Exponence, and Flexivity in Hindukush Languages

Fusion, exponence, and flexivity in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Hanna Rönnqvist Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Master 30 HE credits General Linguistics Spring term 2015 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examiner: Henrik Liljegren Fusion, exponence, and flexivity in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Hanna Rönnqvist Abstract Surrounding the Hindukush mountain chain is a stretch of land where as many as 50 distinct languages varieties of several language meet, in the present study referred to as “The Greater Hindukush” (GHK). In this area a large number of languages of at least six genera are spoken in a multi-linguistic setting. As the region is in part characterised by both contact between languages as well as isolation, it constitutes an interesting field of study of similarities and diversity, contact phenomena and possible genealogical connections. The present study takes in the region as a whole and attempts to characterise the morphology of the many languages spoken in it, by studying three parameters: phonological fusion, exponence, and flexivity in view of grammatical markers for Tense-Mood-Aspect, person marking, case marking, and plural marking on verbs and nouns. The study was performed with the perspective of areal typology, employed grammatical descriptions, and was in part inspired by three studies presented in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS). It was found that the region is one of high linguistic diversity, even if there are common traits, especially between languages of closer contact, such as the Iranian and the Indo-Aryan languages along the Pakistani-Afghan border where purely concatenative formatives are more common. -

Divergence of Altai Macro System Languages and Issues of Their Genetic Relationship O. Sapashev* A. Smailova** B. Zhaksymov

Türkbilig, 2016/31: 109-126. DIVERGENCE OF ALTAI MACRO SYSTEM LANGUAGES AND ISSUES OF THEIR GENETIC RELATIONSHIP O. SAPASHEV* A. SMAILOVA** B. ZHAKSYMOV*** Abstract: Scientists recognize the difficulties associated with final and perfect solution of the problem of origin of the Altai community. The most important issue according to their opinion is a difficulty in differentiation of elements of a possible genetic commonality, the traces of which can be found in all Altaic languages, from the secondary elements of community, developing in different periods of close contacts of various Altaic peoples for at least of two millennia period. Mutual lexical borrowings of not only from single Altaic languages, but also borrowings from non-Altaic languages (the phenomenon of the substrate or super stratum) led to a significant lexical generality of secondary order and gave the reasons for establishment of various kinds of correspondences not relating to common Altaic protolanguage heritage that creates a large difficult to apply comparative- historical method. Keywords: Altaic, macro-system, genetic kinship, language typology, the rudiments Altay Makro Sistemi Dillerinin Farklılıkları ve Onların Genetik İlişkilerine Dair Konular Özet: Altayistik çalışan araştırmacıları, Altay toplumun kökeni sorununun nihai ve mükemmel bir çözümüyle ilişkili olan zorluklar bekler. Araştırmacıların görüşüne göre en önemli konu, olası genetik ortaklık unsurlarının ve Altay dillerinde bulunabilecek izlerin farklılaşması zorluğudur. Bu zorluklar, toplumun ikincil unsurlarından kaynaklanır ve farklı zamanlarda çeşitli Altay topluluklarının en az iki bin yıllık yakın ilişkiler sonucu gelişmiştir. Sadece Altay dilleri ve Altay dilleri dışındaki dillerden karşılıklı sözcük alışverişi (altkatman ve üstkatman olgusu) ikincil seviyede önemli sözcüksel genellemeler ortaya çıkardı ve tarihi-karşılaştırmalı metodun uygulanmasını zorlaştıran ortak proto Altay dil mirasıyla ilgili olmayan bir yapının oluşmasına neden oldu.