Contact in Siberian Languages Brigitte Pakendorf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Grammatical Gender in Hindukush Languages

Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General linguistics Bachelor's programme in Linguistics Spring term 2016 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examinator: Bernhard Wälchli Expert reviewer: Emil Perder Project affiliation: “Language contact and relatedness in the Hindukush Region,” a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (421-2014-631) Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Abstract In the mountainous area of the Greater Hindukush in northern Pakistan, north-western Afghanistan and Kashmir, some fifty languages from six different genera are spoken. The languages are at the same time innovative and archaic, and are of great interest for areal-typological research. This study investigates grammatical gender in a 12-language sample in the area from an areal-typological perspective. The results show some intriguing features, including unexpected loss of gender, languages that have developed a gender system based on the semantic category of animacy, and languages where this animacy distinction is present parallel to the inherited gender system based on a masculine/feminine distinction found in many Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords Grammatical gender, areal-typology, Hindukush, animacy, nominal categories Grammatiskt genus i Hindukush-språk En areal-typologisk studie Julia Lautin Sammanfattning I den här studien undersöks grammatiskt genus i ett antal språk som talas i ett bergsområde beläget i norra Pakistan, nordvästra Afghanistan och Kashmir. I området, här kallat Greater Hindukush, talas omkring 50 olika språk från sex olika språkfamiljer. Det stora antalet språk tillsammans med den otillgängliga terrängen har gjort att språken är arkaiska i vissa hänseenden och innovativa i andra, vilket gör det till ett intressant område för arealtypologisk forskning. -

The Eskimo Language Work of Aleksandr Forshtein

Alaska Journal of Anthropology Volume 4, Numbers 1-2 The Eskimo Language Work of Aleksandr Forshtein Michael E. Krauss Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, AK 99775, ff [email protected] Abstract: Th e paper focuses on another aspect of the legacy of the late Russian Eskimologist Aleksandr Forshtein (1904-1968), namely his linguistic materials and his publications in Eskimo languages and early Russian/Soviet school programs in Siberian Yupik. During the 1930s, the Russians launched an impressive program in developing writing systems, education, and publication in several Native Siberian languages. Forshtein and his mentor, Waldemar Bogoras, took active part in those eff orts on behalf of Siberian Yupik. Th e paper reviews Forshtein’s (and Bogoras’) various contributions to Siberian Yupik language work and language documentation. As it turned out, Forshtein’s, as well as Bogoras’ approach had many fl aws; several colleagues of Forshtein achieved better results and produced alternative writing systems for Siberian Yupik language. Th is review of the early Russian language work on Siberian Yupik is given against the backdrop of many colorful personalities involved and of the general conditions of Russian Siberian linguistics during the 1920s and the 1930s. Keywords: A.S. Forshtein, V.G. Bogoraz, K.S. Sergeeva, E. P. Orlova, Yuit Th is paper that evaluates the Eskimo language work of forced me to compromise a freedom taken for granted on Aleksandr Semenovich Forshtein (1904-1968) must begin this side. with a painfully confl icted apology. In the early 1980’s I was invited by Isabelle Kreindler of Haifa University to contrib- Furthermore, I feel the need to warn the reader to bear ute a paper to a collection on Soviet linguists executed or with me that in the recent process of research for the present interned by Stalinist repression in the former USSR during paper, I was repeatedly faced with new discoveries and re- the years 1930-1953 (Kreindler 1985). -

Council for Innovative Research Peer Review Research Publishing System Journal: Journal of Advances in Linguistics Vol 3, No

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KHALSA PUBLICATIONS ISSN 2348-3024 Language Contact, Use and Attitudes among the Chaldo-Assyrians of Baghdad, Iraq: A Sociolinguistic Study Bader S. Dweik, Tiba A. Al-Obaidi Middle East University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of English Language and Literature [email protected] Middle East University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of English Language and Literature [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aimed at investigating the language situation among the Chaldo-Assyrians in Baghdad. The study attempted to answer the following questions: In what domains do the Chaldo-Assyrians of Baghdad use Syriac and Arabic? What are their attitudes towards both languages? To achieve the goal of this study, the researchers selected a sample that consisted of (135) Chaldo-Assyrians of different age, gender and educational background. The instruments used in this study were interviews and a questionnaire which comprised two different areas: domains of language use and language attitudes. The researchers concluded that the Chaldo-Assyrians in Baghdad used Syriac in different domains mainly at home, in religious settings and in their inner speech; and used it side by side with Arabic in many other social domains such as neighborhood, place of work, media and other public places. The study revealed that the attitudes of the Chaldo- Assyrians towards Syriac and Arabic were highly positive. Finally, the researchers recommended conducting similar studies on other ethnic groups in Baghdad like Turkumans, Kurds, Armenians and Sabians. Indexing terms/Keywords Language Contact; Use; Attitudes; Chaldo-Assyrians; Iraq. -

Contents Abbreviations of the Names of Languages in the Statistical Maps

V Contents Abbreviations of the names of languages in the statistical maps. xiii Abbreviations in the text. xv Foreword 17 1. Introduction: the objectives 19 2. On the theoretical framework of research 23 2.1 On language typology and areal linguistics 23 2.1.1 On the history of language typology 24 2.1.2 On the modern language typology ' 27 2.2 Methodological principles 33 2.2.1 On statistical methods in linguistics 34 2.2.2 The variables 41 2.2.2.1 On the phonological systems of languages 41 2.2.2.2 Techniques in word-formation 43 2.2.2.3 Lexical categories 44 2.2.2.4 Categories in nominal inflection 45 2.2.2.5 Inflection of verbs 47 2.2.2.5.1 Verbal categories 48 2.2.2.5.2 Non-finite verb forms 50 2.2.2.6 Syntactic and morphosyntactic organization 52 2.2.2.6.1 The order in and between the main syntactic constituents 53 2.2.2.6.2 Agreement 54 2.2.2.6.3 Coordination and subordination 55 2.2.2.6.4 Copula 56 2.2.2.6.5 Relative clauses 56 2.2.2.7 Semantics and pragmatics 57 2.2.2.7.1 Negation 58 2.2.2.7.2 Definiteness 59 2.2.2.7.3 Thematic structure of sentences 59 3. On the typology of languages spoken in Europe and North and 61 Central Asia 3.1 The Indo-European languages 61 3.1.1 Indo-Iranian languages 63 3.1.1.1New Indo-Aryan languages 63 3.1.1.1.1 Romany 63 3.1.2 Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1 South-West Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1.1 Tajiki 65 3.1.2.2 North-West Iranian languages 68 3.1.2.2.1 Kurdish 68 3.1.2.2.2 Northern Talysh 70 3.1.2.3 South-East Iranian languages 72 3.1.2.3.1 Pashto 72 3.1.2.4 North-East Iranian languages 74 3.1.2.4.1 -

FSC National Risk Assessment

FSC National Risk Assessment for the Russian Federation DEVELOPED ACCORDING TO PROCEDURE FSC-PRO-60-002 V3-0 Version V1-0 Code FSC-NRA-RU National approval National decision body: Coordination Council, Association NRG Date: 04 June 2018 International approval FSC International Center, Performance and Standards Unit Date: 11 December 2018 International contact Name: Tatiana Diukova E-mail address: [email protected] Period of validity Date of approval: 11 December 2018 Valid until: (date of approval + 5 years) Body responsible for NRA FSC Russia, [email protected], [email protected] maintenance FSC-NRA-RU V1-0 NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 2018 – 1 of 78 – Contents Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for the Russian Federation ................................................. 3 1 Background information ........................................................................................................... 4 2 List of experts involved in risk assessment and their contact details ........................................ 6 3 National risk assessment maintenance .................................................................................... 7 4 Complaints and disputes regarding the approved National Risk Assessment ........................... 7 5 List of key stakeholders for consultation ................................................................................... 8 6 List of abbreviations and Russian transliterated terms* used ................................................... 8 7 Risk assessments -

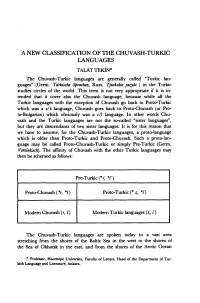

A New Classification of the Chuvash-Turkic Languages

A NEW CLASSİFICATİON OF THE CHUVASH-TURKIC LANGUAGES T A L Â T TEKİN * The Chuvash-Turkic languages are generally called “Turkic lan guages” (Germ. Türkische Sprachen, Russ. Tjurkskie jazyki ) in the Turkic studies circles of the world. This term is not very appropriate if it is in- tended that it cover also the Chuvash language, because while ali the Turkic languages with the exception of Chuvash go back to Proto-Turkic vvhich was a z/s language, Chuvash goes back to Proto-Chuvash (or Pro- to-Bulgarian) vvhich obviously was a r/l language. In other vvords Chu vash and the Turkic languages are not the so-called “sister languages”, but they are descendants of two sister languages. It is for this reason that we have to assume, for the Chuvash-Turkic languages, a proto-language vvhich is older than Proto-Turkic and Proto-Chuvash. Such a proto-lan- guage may be called Proto-Chuvash-Turkic or simply Pre-Turkic (Germ. Vortürkisch). The affinity of Chuvash vvith the other Turkic languages may then be schemed as follovvs: Pre-Turkic i*r, * i ) Proto-Chuvash ( *r, */) Proto-Turkic (* z, *s) Modem Chuvash (r, l) Modem Turkic languages (z, s ) The Chuvash-Turkic languages are spoken today in a vast area stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the vvest to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in the east, and from the shores of the Arctic Ocean * Professor, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Letters, Head of the Department of Tur- kish Language and Literatüre, Ankara. ■30 TALÂT TEKİN in the north to the shores of Persian Gulf in the south. -

Events and Land Reform in Russia

3 TITLE: EVENKS AND LAND REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROGRESS AND OBSTACLES AUTHOR: GAIL FONDAHL University of Northern British Columbia THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE VIII PROGRAM 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION:1 CONTRACTOR: Dartmouth College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Gail Fondahl COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER: 808-28 DATE: March 1, 1996 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded by Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within the Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, or make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without the written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law. 1 The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s). EVENKS AND LAND REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROGRESS AND OBSTACLES Gail Fondahl1 The Evenks are one of most populous indigenous peoples of Siberia (with 30,247 individuals, according to a 1989 census), inhabiting an area stretching from west of the Yenisey River to the Okhotsk seaboard and Sakhalin Island, and from the edge of the tundra south to China and Mongolia. -

Climate Change and Human Mobility in Indigenous Communities of the Russian North

Climate Change and Human Mobility in Indigenous Communities of the Russian North January 30, 2013 Susan A. Crate George Mason University Cover image: Winifried K. Dallmann, Norwegian Polar Institute. http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about/maps. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction and Purpose ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Focus of paper and author’s approach................................................................................... 2 1.2 Human mobility in the Russian North: Physical and Cultural Forces .................................. 3 1.2.1 Mobility as the Historical Rule in the Circumpolar North ............................................. 3 1.2.2. Changing the Rules: Mobility and Migration in the Russian and Soviet North ............ 4 1.2.3 Peoples of the Russian North .......................................................................................... 7 1.2.4 The contemporary state: changes affecting livelihoods ................................................. 8 2. Overview of the physical science: actual and potential effects of climate change in the Russian North .............................................................................................................................................. -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

Genetic Analysis of Male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian Paternal Lineages of the Conquering Hungarian Tribes

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2020) 12: 31 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes Erzsébet Fóthi1 & Angéla Gonzalez2 & Tibor Fehér3 & Ariana Gugora4 & Ábel Fóthi5 & Orsolya Biró6 & Christine Keyser2,7 Received: 11 March 2019 /Accepted: 16 October 2019 /Published online: 14 January 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract According to historical sources, ancient Hungarians were made up of seven allied tribes and the fragmented tribes that split off from the Khazars, and they arrived from the Eastern European steppes to conquer the Carpathian Basin at the end of the ninth century AD. Differentiating between the tribes is not possible based on archaeology or history, because the Hungarian Conqueror artifacts show uniformity in attire, weaponry, and warcraft. We used Y-STR and SNP analyses on male Hungarian Conqueror remains to determine the genetic source, composition of tribes, and kin of ancient Hungarians. The 19 male individuals paternally belong to 16 independent haplotypes and 7 haplogroups (C2, G2a, I2, J1, N3a, R1a, and R1b). The presence of the N3a haplogroup is interesting because it rarely appears among modern Hungarians (unlike in other Finno-Ugric-speaking peoples) but was found in 37.5% of the Hungarian Conquerors. This suggests that a part of the ancient Hungarians was of Ugric descent and that a significant portion spoke Hungarian. We compared our results with public databases and discovered that the Hungarian Conquerors originated from three distant territories of the Eurasian steppes, where different ethnicities joined them: Lake Baikal- Altai Mountains (Huns/Turkic peoples), Western Siberia-Southern Urals (Finno-Ugric peoples), and the Black Sea-Northern Caucasus (Caucasian and Eastern European peoples). -

Das Jukagirische Im Kreise Der Nostratischen Sprachen

Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 130 (2013): 171–190 DOI 10.4467/20834624SL.13.011.1142 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen [email protected] DAS JUKAGIRISCHE IM KREISE DER NOSTRATISCHEN SPRACHEN Keywords: Yukaghir languages, Nostratic linguistics, Uralo-Yukaghir question, treat- ment of Yukaghir by Nostraticists, history of linguistics Abstract The Yukaghir language as a member of the Nostratic family of languages The article deals with the treatment of Yukaghir languages (Tundra-Y., Kolyma-Y., Chuvan, Omok) by several prominent Nostraticists (H. Pedersen, V. M. Illič-Svityč, J. H. Greenberg, A. R. Bomhard, K. H. Menges, V. Blažek, A. B. Dolgopol’skij). The author gives an overview on their attempts of different quality to relate the Yukaghir languages with the Nostratic family and sketches some omnicomparativists’ hypothesises on macro-families such as “Uralo-Yukaghir” or “Eurasiatic”. 1. Einleitung Daß der Titel des vorliegenden Beitrages den Leser zunächst etwas befremden dürfte, ist vom Vf. durchaus beabsichtigt, erweckt er doch den Anschein, als entspräche es der Intention des Autors, die Zugehörigkeit der jukagirischen Sprachen (Tundra- Jukagirisch, Kolyma-Jukagirisch, Omokisch u. Čuvanisch) zu den nostratischen Sprachen zu postulieren. Würde ein solcher Versuch auf Anhieb einigermaßen grotesk erscheinen, so ist doch anzumerken, daß eine Reihe von Nostratikern, dies ernsthaft in Erwägung ziehen, und entsprechende Überlegungen durchaus immer wieder Befürworter finden. Auch sind entsprechende Versuche keineswegs neu und, bezieht man die Spekulationen hinsichtlich der sogenannten „Uralo-Jukagirischen“ 172 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL Hypothese1 in die Betrachtungen ein, sogar folgerichtig (wird das Proto-Uralische von den Nostratikern doch als eine „Tochtersprache“ des [Proto-]Nostratischen angesehen). Inzwischen ist eine ganze Reihe von Arbeiten, in denen auch die jukagi- rischen Befunde für diverse [Re-]Konstruktionen berücksichtigt wurden, erschienen.