Non-Canonical SAY in Siberia Areal and Genealogical Patterns*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Grammatical Gender in Hindukush Languages

Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Department of Linguistics Independent Project for the Degree of Bachelor 15 HEC General linguistics Bachelor's programme in Linguistics Spring term 2016 Supervisor: Henrik Liljegren Examinator: Bernhard Wälchli Expert reviewer: Emil Perder Project affiliation: “Language contact and relatedness in the Hindukush Region,” a research project supported by the Swedish Research Council (421-2014-631) Grammatical gender in Hindukush languages An areal-typological study Julia Lautin Abstract In the mountainous area of the Greater Hindukush in northern Pakistan, north-western Afghanistan and Kashmir, some fifty languages from six different genera are spoken. The languages are at the same time innovative and archaic, and are of great interest for areal-typological research. This study investigates grammatical gender in a 12-language sample in the area from an areal-typological perspective. The results show some intriguing features, including unexpected loss of gender, languages that have developed a gender system based on the semantic category of animacy, and languages where this animacy distinction is present parallel to the inherited gender system based on a masculine/feminine distinction found in many Indo-Aryan languages. Keywords Grammatical gender, areal-typology, Hindukush, animacy, nominal categories Grammatiskt genus i Hindukush-språk En areal-typologisk studie Julia Lautin Sammanfattning I den här studien undersöks grammatiskt genus i ett antal språk som talas i ett bergsområde beläget i norra Pakistan, nordvästra Afghanistan och Kashmir. I området, här kallat Greater Hindukush, talas omkring 50 olika språk från sex olika språkfamiljer. Det stora antalet språk tillsammans med den otillgängliga terrängen har gjort att språken är arkaiska i vissa hänseenden och innovativa i andra, vilket gör det till ett intressant område för arealtypologisk forskning. -

Contents Abbreviations of the Names of Languages in the Statistical Maps

V Contents Abbreviations of the names of languages in the statistical maps. xiii Abbreviations in the text. xv Foreword 17 1. Introduction: the objectives 19 2. On the theoretical framework of research 23 2.1 On language typology and areal linguistics 23 2.1.1 On the history of language typology 24 2.1.2 On the modern language typology ' 27 2.2 Methodological principles 33 2.2.1 On statistical methods in linguistics 34 2.2.2 The variables 41 2.2.2.1 On the phonological systems of languages 41 2.2.2.2 Techniques in word-formation 43 2.2.2.3 Lexical categories 44 2.2.2.4 Categories in nominal inflection 45 2.2.2.5 Inflection of verbs 47 2.2.2.5.1 Verbal categories 48 2.2.2.5.2 Non-finite verb forms 50 2.2.2.6 Syntactic and morphosyntactic organization 52 2.2.2.6.1 The order in and between the main syntactic constituents 53 2.2.2.6.2 Agreement 54 2.2.2.6.3 Coordination and subordination 55 2.2.2.6.4 Copula 56 2.2.2.6.5 Relative clauses 56 2.2.2.7 Semantics and pragmatics 57 2.2.2.7.1 Negation 58 2.2.2.7.2 Definiteness 59 2.2.2.7.3 Thematic structure of sentences 59 3. On the typology of languages spoken in Europe and North and 61 Central Asia 3.1 The Indo-European languages 61 3.1.1 Indo-Iranian languages 63 3.1.1.1New Indo-Aryan languages 63 3.1.1.1.1 Romany 63 3.1.2 Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1 South-West Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1.1 Tajiki 65 3.1.2.2 North-West Iranian languages 68 3.1.2.2.1 Kurdish 68 3.1.2.2.2 Northern Talysh 70 3.1.2.3 South-East Iranian languages 72 3.1.2.3.1 Pashto 72 3.1.2.4 North-East Iranian languages 74 3.1.2.4.1 -

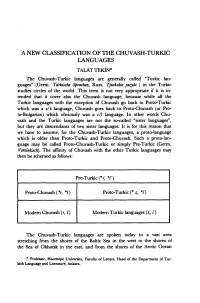

A New Classification of the Chuvash-Turkic Languages

A NEW CLASSİFICATİON OF THE CHUVASH-TURKIC LANGUAGES T A L Â T TEKİN * The Chuvash-Turkic languages are generally called “Turkic lan guages” (Germ. Türkische Sprachen, Russ. Tjurkskie jazyki ) in the Turkic studies circles of the world. This term is not very appropriate if it is in- tended that it cover also the Chuvash language, because while ali the Turkic languages with the exception of Chuvash go back to Proto-Turkic vvhich was a z/s language, Chuvash goes back to Proto-Chuvash (or Pro- to-Bulgarian) vvhich obviously was a r/l language. In other vvords Chu vash and the Turkic languages are not the so-called “sister languages”, but they are descendants of two sister languages. It is for this reason that we have to assume, for the Chuvash-Turkic languages, a proto-language vvhich is older than Proto-Turkic and Proto-Chuvash. Such a proto-lan- guage may be called Proto-Chuvash-Turkic or simply Pre-Turkic (Germ. Vortürkisch). The affinity of Chuvash vvith the other Turkic languages may then be schemed as follovvs: Pre-Turkic i*r, * i ) Proto-Chuvash ( *r, */) Proto-Turkic (* z, *s) Modem Chuvash (r, l) Modem Turkic languages (z, s ) The Chuvash-Turkic languages are spoken today in a vast area stretching from the shores of the Baltic Sea in the vvest to the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk in the east, and from the shores of the Arctic Ocean * Professor, Hacettepe University, Faculty of Letters, Head of the Department of Tur- kish Language and Literatüre, Ankara. ■30 TALÂT TEKİN in the north to the shores of Persian Gulf in the south. -

A Comparative Study on the Sayan Languages (Turkic; Russia and Mongolia)

MASTER THESIS A comparative study on the Sayan languages (Turkic; Russia and Mongolia) Author: Supervisor: Tessa de Mol-van Valen Dr. E.I. Crevels Second reader: Dr. E.L. Stapert A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Research Master of Linguistics June 2017 For Tuba, Leo Hollemans, my students and dear family “Dus er is een taal die hetzelfde heet als ik? En u moet daar een groot werkstuk over schrijven? Wow, heel veel succes!” Acknowledgements I am indebted to my thesis supervisor Dr. E.I. Crevels at Leiden University for her involvement and advice. Thank you for your time, your efforts, your reading, all those comments and suggestions to improve my thesis. It is an honor to finish my study with the woman who started my interest in descriptive linguistics. If it wasn’t for Beschrijvende Taalkunde I, I would not get to know the Siberian languages that well and it would have taken much longer for me to discover my interest in this region. This is also the place where I should thank Dr. E.L. Stapert at Leiden University. Thank you for your lectures on the ethnic minorities of Siberia, where I got to know the Tuba and, later on, also the Tuvan and Tofa. Thank you for this opportunity. Furthermore, I owe deep gratitude to the staff of the Universitätsbibliothek of the Johannes Gutenberg Universität in Mainz, where I found Soyot. Thanks to their presence and the extensive collection of the library, I was able to scan nearly 3000 pages during the Christmas Holiday. -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

Genetic Analysis of Male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian Paternal Lineages of the Conquering Hungarian Tribes

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2020) 12: 31 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes Erzsébet Fóthi1 & Angéla Gonzalez2 & Tibor Fehér3 & Ariana Gugora4 & Ábel Fóthi5 & Orsolya Biró6 & Christine Keyser2,7 Received: 11 March 2019 /Accepted: 16 October 2019 /Published online: 14 January 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract According to historical sources, ancient Hungarians were made up of seven allied tribes and the fragmented tribes that split off from the Khazars, and they arrived from the Eastern European steppes to conquer the Carpathian Basin at the end of the ninth century AD. Differentiating between the tribes is not possible based on archaeology or history, because the Hungarian Conqueror artifacts show uniformity in attire, weaponry, and warcraft. We used Y-STR and SNP analyses on male Hungarian Conqueror remains to determine the genetic source, composition of tribes, and kin of ancient Hungarians. The 19 male individuals paternally belong to 16 independent haplotypes and 7 haplogroups (C2, G2a, I2, J1, N3a, R1a, and R1b). The presence of the N3a haplogroup is interesting because it rarely appears among modern Hungarians (unlike in other Finno-Ugric-speaking peoples) but was found in 37.5% of the Hungarian Conquerors. This suggests that a part of the ancient Hungarians was of Ugric descent and that a significant portion spoke Hungarian. We compared our results with public databases and discovered that the Hungarian Conquerors originated from three distant territories of the Eurasian steppes, where different ethnicities joined them: Lake Baikal- Altai Mountains (Huns/Turkic peoples), Western Siberia-Southern Urals (Finno-Ugric peoples), and the Black Sea-Northern Caucasus (Caucasian and Eastern European peoples). -

Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic Language of Siberia Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov

Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov To cite this version: Brigitte Pakendorf, Innokentij Novgorodov. Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia. In Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor. Loanwords in the World’s Languages: a Comparative Handbook, de Gruyter Mouton, pp.496-524, 2009. hal-02012602 HAL Id: hal-02012602 https://hal.univ-lyon2.fr/hal-02012602 Submitted on 23 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 19 Loanwords in Sakha (Yakut), a Turkic language of Siberia* Brigitte Pakendorf and Innokentij N. Novgorodov 1. The language and its speakers Sakha (often referred to as Yakut) is a Turkic language spoken in northeastern Siberia. It is classified as a Northeastern Turkic language together with South Sibe- rian Turkic languages such as Tuvan, Altay, and Khakas. This classification, however, is based primarily on geography, rather than shared linguistic innovations (Schönig 1997: 123; Johanson 1998: 82f); thus, !"erbak (1994: 37–42) does not include Sakha amongst the South Siberian Turkic languages, but considers it a separate branch of Turkic. The closest relative of Sakha is Dolgan, spoken to the northwest of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). -

Das Jukagirische Im Kreise Der Nostratischen Sprachen

Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 130 (2013): 171–190 DOI 10.4467/20834624SL.13.011.1142 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen [email protected] DAS JUKAGIRISCHE IM KREISE DER NOSTRATISCHEN SPRACHEN Keywords: Yukaghir languages, Nostratic linguistics, Uralo-Yukaghir question, treat- ment of Yukaghir by Nostraticists, history of linguistics Abstract The Yukaghir language as a member of the Nostratic family of languages The article deals with the treatment of Yukaghir languages (Tundra-Y., Kolyma-Y., Chuvan, Omok) by several prominent Nostraticists (H. Pedersen, V. M. Illič-Svityč, J. H. Greenberg, A. R. Bomhard, K. H. Menges, V. Blažek, A. B. Dolgopol’skij). The author gives an overview on their attempts of different quality to relate the Yukaghir languages with the Nostratic family and sketches some omnicomparativists’ hypothesises on macro-families such as “Uralo-Yukaghir” or “Eurasiatic”. 1. Einleitung Daß der Titel des vorliegenden Beitrages den Leser zunächst etwas befremden dürfte, ist vom Vf. durchaus beabsichtigt, erweckt er doch den Anschein, als entspräche es der Intention des Autors, die Zugehörigkeit der jukagirischen Sprachen (Tundra- Jukagirisch, Kolyma-Jukagirisch, Omokisch u. Čuvanisch) zu den nostratischen Sprachen zu postulieren. Würde ein solcher Versuch auf Anhieb einigermaßen grotesk erscheinen, so ist doch anzumerken, daß eine Reihe von Nostratikern, dies ernsthaft in Erwägung ziehen, und entsprechende Überlegungen durchaus immer wieder Befürworter finden. Auch sind entsprechende Versuche keineswegs neu und, bezieht man die Spekulationen hinsichtlich der sogenannten „Uralo-Jukagirischen“ 172 MICHAEL KNÜPPEL Hypothese1 in die Betrachtungen ein, sogar folgerichtig (wird das Proto-Uralische von den Nostratikern doch als eine „Tochtersprache“ des [Proto-]Nostratischen angesehen). Inzwischen ist eine ganze Reihe von Arbeiten, in denen auch die jukagi- rischen Befunde für diverse [Re-]Konstruktionen berücksichtigt wurden, erschienen. -

Indigenous Languages Indigenous Languages Are Disappearing WHY DO LANGUAGES DIE?

Issue 9 Under Sail Newspaper March 2019 other languages that are spoken? Do they have future or are they condemned to die? Indigenous languages Languages play a crucial role in the daily lives of people, not only as a tool for communication, education, social integration and development, but also as a repository for each person's unique identity, cultural history, traditions and memory. However, despite their immense value, languages around the world continue to disappear at an alarming rate. In an article recently published in The New With this in mind, the United Nations Yorker, the issue of endangered languages is declared 2019 The Year of Indigenous explored in depth. They report a concern that Languages (IY2019) in order to raise up to half of today’s living languages are in awareness of them, not only to benefit the danger and will be extinct by the end of the people who speak these languages, but also 21st century. This means a language dies on for others to appreciate the important average every four months. contribution they make to our world's rich cultural diversity. Indigenous languages are disappearing In today’s globalized world, language usage is changing rapidly. English is the dominant language of the internet. More people now have a working knowledge of English as a WHY DO LANGUAGES DIE? second (or third) language than the number of people who consider English their mother Languages die for many reasons. Some are tongue. At the same time, more than three cultural. For example, many cultures have billion people – nearly half of the world’s been colonized or otherwise dominated by current population – speak one of only 20 another culture. -

Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map

SVENSKA FORSKNINGSINSTITUTET I ISTANBUL SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL SKRIFTER — PUBLICATIONS 5 _________________________________________________ Lars Johanson Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul Stockholm 2001 Published with fõnancial support from Magn. Bergvalls Stiftelse. © Lars Johanson Cover: Carte de l’Asie ... par I. M. Hasius, dessinée par Aug. Gottl. Boehmius. Nürnberg: Héritiers de Homann 1744 (photo: Royal Library, Stockholm). Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala 2001 ISBN 91-86884-10-7 Prefatory Note The present publication contains a considerably expanded version of a lecture delivered in Stockholm by Professor Lars Johanson, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, on the occasion of the ninetieth birth- day of Professor Gunnar Jarring on October 20, 1997. This inaugu- rated the “Jarring Lectures” series arranged by the Swedish Research Institute of Istanbul (SFII), and it is planned that, after a second lec- ture by Professor Staffan Rosén in 1999 and a third one by Dr. Bernt Brendemoen in 2000, the series will continue on a regular, annual, basis. The Editors Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Linguistic documentation in the field The topic of the present contribution, dedicated to my dear and admired colleague Gunnar Jarring, is linguistic fõeld research, journeys of discovery aiming to draw the map of the Turkic linguistic world in a more detailed and adequate way than done before. The survey will start with the period of the classical pioneering achievements, particu- larly from the perspective of Scandinavian Turcology. It will then pro- ceed to current aspects of language documentation, commenting brief- ly on a number of ongoing projects that the author is particularly fami- liar with. -

Russia 2020 Human Rights Report

RUSSIA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Russian Federation has a highly centralized, authoritarian political system dominated by President Vladimir Putin. The bicameral Federal Assembly consists of a directly elected lower house (State Duma) and an appointed upper house (Federation Council), both of which lack independence from the executive. The 2016 State Duma elections and the 2018 presidential election were marked by accusations of government interference and manipulation of the electoral process, including the exclusion of meaningful opposition candidates. On July 1, a national vote held on constitutional amendments did not meet internationally recognized electoral standards. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service, the Investigative Committee, the Office of the Prosecutor General, and the National Guard are responsible for law enforcement. The Federal Security Service is responsible for state security, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism, as well as for fighting organized crime and corruption. The national police force, under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, is responsible for combating all crime. The National Guard assists the Federal Security Service’s Border Guard Service in securing borders, administers gun control, combats terrorism and organized crime, protects public order, and guards important state facilities. The National Guard also participates in armed defense of the country’s territory in coordination with Ministry of Defense forces. Except in rare cases, security forces generally report to civilian authorities. National-level civilian authorities have, at best, limited control over security forces in the Republic of Chechnya, which are accountable only to the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov. Members of the Russian security forces committed numerous human rights abuses.