Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

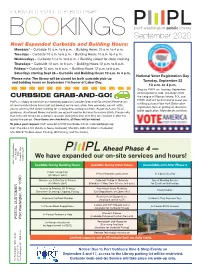

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

Read the Full Report As an Adobe Acrobat

CREATING A PUBLIC SQUARE IN A CHALLENGING MEDIA AGE A White Paper on the Knight Commission Report on Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in the Digital Age Norman J. Ornstein with John C. Fortier and Jennifer Marsico Executive Summary Much has changed in media and communications costs. Newspapers would benefit from looser technologies over the past fifty years. Today we face the rules and more flexibility. News organizations dual problems of an increasing gap in access to these should be able to work together to collect technologies between the “haves” and “have nots” and payment for content access. fragmentation of the once-common set of facts that 2. Implement government subsidies. With high Americans shared through similar experiences with the costs of operation, the newspaper industry media. This white paper lays out four major challenges should be eligible for lower postal rates and that the current era poses and proposes ways to meet exemptions from sales taxes. these challenges and boost civic participation. 3. Change the tax status of papers, making them tax-exempt in some fashion. This could Challenge One: Keeping Newspapers Alive involve categorizing newspapers as “bene- fit” or “flexible purpose” corporations, or Until They Are Well treating them as for-profit businesses that have a charitable or educational purpose. A large part of the average newspaper budget com- prises costs related to printing, bundling, and deliv- ery. The development of new delivery models could greatly reduce (or perhaps eliminate) these Challenge Two: Universal Access and expenses. Potential new models use screen- Adequate Spectrum technology advancement (using new tools like the iPad) and raise subscription revenue online. -

And the Masonic Family of Idaho

The Freemasons and the Masonic Family of Idaho Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Idaho 219 N. 17th St., Boise, ID 83702 US Tel: +1-208-343-4562 Fax: +1 208-343-5056 Email: [email protected] Web: www.idahomasons.org First Printing: June 2015 online 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Attraction of Freemasonry ............................................................................................................................ 5 What they say about Freemasonry.... ........................................................................................................... 6 Grand Lodge of Idaho Territory ‐ The Beginning .......................................................................................... 7 Freemasons and Charity ............................................................................................................................... 9 Our Mission: .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Child Identification Program: .................................................................................................................... 9 Bikes for Books .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Organization Information ........................................................................................................................ -

We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses Nutrition and Health Sciences, Department of 6-2017 We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program on the Home Environment Courtney Warday University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nutritiondiss Warday, Courtney, "We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program on the Home Environment" (2017). Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses. 72. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nutritiondiss/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition and Health Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WE COOK: FUN WITH FOOD AND FITNESS: IMPACT OF A YOUTH COOKING PROGRAM ON THE HOME ENVIRONMENT By Courtney Warday A THESIS Presented to the Faulty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Nutrition & Health Sciences Under the Supervision of Professors Linda Boeckner & Michelle Krehbiel Lincoln, Nebraska June 2017 WE COOK: FUN WITH FOOD AND FITNESS: IMPACT OF A YOUTH COOKING PROGRAM ON THE HOME ENVIRONMENT Courtney Warday, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisors: Linda Boeckner & Michelle Krehbiel BACKGROUND US food preparation habits have decreased since 1965 (Smith, et al, 2013). Children are rarely involved in food preparation in the home (Fulkerson, et al, 2008). -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 463-001 Interviewee: Sharon Huntley Kahn Interviewer: Donna McCrea Date of Interview: July 10, 2018 Donna McCrea: This is Donna McCrea, Head of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana. Today is July 10th of 2018. Today I'm interviewing Sharon Huntley Kahn about her father Chet Huntley. I'll note that the focus of the interview will really be on things that you know about Chet Huntley that other people would maybe not have known: things that have not been made public already or don't appear in many of the biographical materials and articles about him. Also, I'm hoping that you'll share some stories that you have about him and his life. So I'm going to begin by saying I know that you grew up in Los Angeles. Can you maybe start there and talk about your memories about your father and your time in L.A.? Sharon Kahn: Yes, Donna. Before we begin, I just want to say how nice it is to work with you. From the beginning our first phone conversations, I think at least a year and a half ago, you've always been so welcoming and interested, and it's wonderful to be here and I'm really happy to share inside stories with you. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT in AMERICA By. Sean P Mccracken "CBS NEWS Now Projects...NBC NEWS Is Read

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT IN AMERICA By. Sean P McCracken "CBS NEWS now projects...NBC NEWS is ready to declare ...ABC NEWS is now making a call in....CNN now estimates...declares...projects....calls...predicts...retracts..." We hear these few opening words and wait on the edges of our seats as the names and places which follow these familiar predicates make very well be those which tell us in the United States who will occupy the White House for the next four years. We hear the words, follow the talking-heads and read the ever changing scripts which scroll, flash or blink across our television screens. It is a ritual that has been repeated an-masse every four years since 1952...and for a select few, 1948. Since its earliest days, television has had a love affair with politics, albeit sometimes a strained one. From the first primitive experiments at the Republican National Convention in 1940, to the multi angled, figure laden, information over-loaded spectacles of today, the "happening" that unfolds every four years on the second Tuesday in November, known as "Election Night" still holds a special place in either our heart...or guts. Somehow, it still manages to keep us glued to our television for hours on end. This one night that rolls around every four years has "grown up" with many of us over the last 64 years. Staring off as little more than chalk boards, name plates and radio announcers plopped in front of large, monochromatic cameras that barely sent signals beyond the limits of New York City and gradually morphing into color-laden, graphic-filled, information packed, multi channel marathons that can be seen by virtually...and virtually seen by...almost any human on the planet. -

SEE IT THEN: Notes on Television Journalism \

J NimMAN RmPORTS SEE IT THEN: Notes on Television Journalism by Robert Drew Television this year will break the one billion dollar own? Will the total effect of TV be to divert our minds mark in advertising sales. In .1956, the National Broad with soporific fantasies, or to make us more aware of our casting Company predicts, television will do almost. own real problems? - two billion dollars worth of business. Jolin Crosby, There were these questions and others, and there were TV columnist for the New York Herald Tribune, was a the discussions from which the following notes are ex little sceptical of the NBC estimate. "Golly!" he said. cerpted, but there were no answers. Glir;npsers of answers "Th:J.t sounds big to me. NBC's predictiom in the past will proceed at their own peril. have all turned out to be wrong, but they've been wrong on the low side." The definition of TV journalism properly ought to in· Vincent S. Jones, director of the news ~ and editorial office dude everything from a news bulletin to a national con of the Gannett Newspapers, who is studying the impact vention. I have made certain assumptions in order to of TV on journalism, thinks that the impact is considerable narrow the definition down to those areas where significant and growing. "We have been hopelessly outdistanced in character changes might be brewing. I have . ·assumed speed by radio and in depth and quality by the maga- . rv. that panel discussions and live reporting of conventions, zines, and we have lost both prestige and glamour," he said. -

The Legends at Village West Offers Visitors a Walk Through Kansas History

The Legends at Village West The Legends at Village West Offers Visitors a Walk through Kansas History The Legends at Village West, offers a new component to the one-of-a-kind experience found at the center: education. Along with shopping, dining and entertainment, visitors of all ages can enjoy an audio walking tour of the more than 80 Kansas legends represented visually on medallions, post- ers, murals and in sculpture throughout the center. The Legends honors legends of Kansas in athletics, music, exploration, science, technology, poli- tics, art and much more, recognizing the things that truly make the state unique. The legends theme is interwoven through the landscape, hardscape, amenities and architectural motif, offering a glimpse into Kansas’ history, heritage and environment. Each corridor and courtyard of the center is dedicated to a particular category of famous Kansans or aspect of the state and its history. A free self-guided audio walking tour leads visitors through each corridor, providing information about the legends and the artistic representations in which they are depicted. The Legends is proud to provide such a uniquely fun and educational option for visitors looking to enhance a traditional shopping excursion. The tour was created for listeners of all ages and is ideal for class projects, field trips and family outings. The self-guided audio tour allows visitors to move at their own pace, spending as much time as desired at each of the 28 stops along the way and anywhere in between. The easy-to-use audio player is perfect for all ages, providing listeners the opportunity to pause, move forward or move backward at any time for a completely customized experience. -

®Hf Tm\ School Lo the Tune of J.1-0, Nt L,U/.7I If Messliin Urged East Haveners Thai Orgaiiiznlion's Biennial Din Room

',TV^Tr?..i-S'.'Ert-.*5'«sn«-4.Trjw.'»-s;"iWf" •' '""•" i" ucub uixMQn Hagamun Mem. Library Bast Hnven, Thur. June 9, 1955. Branford R-nVw-Eait Haven News 8 Conn. 5-4 Coach Crisafi —« E. H. Catholic red perch. , , _ E.H.H.S. Blasts Boardman, 13 To 0; . ((.ontlniied I>om I'agc One) librarian and then be allowed to DANOINQ catch one "fish" Xor each book i Members of the school system Our Telephone Numbers lug program Is lielng arranged Women At Dinner read. i will act as JUd(?es and the win ^^ is buck al * / Crisafiincn Face ScymourTomorrow with itneinberR of the press ami The contestant then Writes his ner will be Judged on the num ber of book.s rend, types of An Independent I^r-liniriK Iheli- K'i"« for n vie clergy to be senb.'d at the head name on' one side of the fish, Kdiloriah llOhari 7.S«11 Held In Cheshire iMoks and a report made on one PALMERS CASINO fury over .Seymour tomorrow; f^ast Unveil tdhle. , The ^dinner, which will nnd the name of the book read Twenty two ICasI Hnv(?ii mem of the books. The fourth the high whool bnsehall cnnnon- ab be hold at; tho Weeplifig Willows on the other side. This fish will INDIAN NECK BRANFORD, CONN. bers of the New Haven Council bo dropped Into a' box on the through seventh grade contest Weekly Newspaper ndefl hapless Boardman Trade MauHe 2b .1 will liegin at (i.'OT p. in. ants will be awarded prizes on a ,1 of Calholic Women. -

Horny Toads and Ugly Chickens: a Bibliography on Texas in Speculative Fiction

HORNY TOADS AND UGLY CHICKENS: A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON TEXAS IN SPECULATIVE FICTION by Bill Page Dellwood Press Bryan, Texas June 2010 1 HORNY TOADS AND UGLY CHICKENS: A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON TEXAS IN SPECULATIVE FICTION by Bill Page In this bibliography I have compiled a list of science fiction, fantasy and horror novels that are set in Texas. I have mentioned several short stories and a few poems and plays in this bibliography, but I did not make any sustained attempt to identify such works. I have not listed works of music, though many songs exist which deal with these subjects. Most entries are briefly annotated, though I well understand that it is impossible to accurately describe a book in only one or two sentences. As one reads science fiction and fantasy novels set in Texas, certain themes repeat themselves. There are, of course, numerous works about ghosts, vampires, and werewolves. Authors often write about invasions of the state, not only by creatures from outer space, but also by foreigners, including the Russians, the Germans, the Mexicans, the Japanese and even the Israelis. One encounters familiar plot devices, such as time travel, in other books. Stories often depict a Texas devastated by some apocalypse – sometimes it is global warming, sometimes World War III has been fought, and usually lost, by the United States, and, in one case, the disaster consisted of a series of massive earthquakes which created ecological havoc and destroyed most of the region's infrastructure. The mystique of the old west has long been an alluring subject for authors; even Jules Verne and Bram Stoker used Texans in stories.