Preserving Intellectual Freedom : Fighting Censorship in Our Schools / Edited by Jean F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Obscenity Terms of the Court

Volume 17 Issue 3 Article 1 1972 The Obscenity Terms of the Court O. John Rogge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation O. J. Rogge, The Obscenity Terms of the Court, 17 Vill. L. Rev. 393 (1972). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol17/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Rogge: The Obscenity Terms of the Court Villanova Law Review VOLUME 17 FEBRUARY 1972 NUMBER 3 THE OBSCENITY TERMS OF THE COURT 0. JOHN ROGGEt I. OVERVIEW OF THE 1970-1971 SUPREME COURT OBSCENITY DECISIONS AT ITS OCTOBER 1970-JUNE 1971 TERM, the Supreme Court of the United States had the incredible number of 61 obscenity cases on its docket,' if one includes two cases which involved the use of the four-letter word for the sexual act, in the one case by itself,' and in the other instance with the further social message that this is what one should do with the draft.' These are more such cases than at any previous term, or number of terms for that matter. No less than five of the 61 cases involved the film, I Am Curious (Yellow). Other cases involved such varied forms of expression and entertainment as the fol- lowing: Language of Love, a Swedish -

We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses Nutrition and Health Sciences, Department of 6-2017 We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program on the Home Environment Courtney Warday University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nutritiondiss Warday, Courtney, "We Cook: Fun with Food and Fitness: Impact of a Youth Cooking Program on the Home Environment" (2017). Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses. 72. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nutritiondiss/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition and Health Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition & Health Sciences Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WE COOK: FUN WITH FOOD AND FITNESS: IMPACT OF A YOUTH COOKING PROGRAM ON THE HOME ENVIRONMENT By Courtney Warday A THESIS Presented to the Faulty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Nutrition & Health Sciences Under the Supervision of Professors Linda Boeckner & Michelle Krehbiel Lincoln, Nebraska June 2017 WE COOK: FUN WITH FOOD AND FITNESS: IMPACT OF A YOUTH COOKING PROGRAM ON THE HOME ENVIRONMENT Courtney Warday, M.S. University of Nebraska, 2017 Advisors: Linda Boeckner & Michelle Krehbiel BACKGROUND US food preparation habits have decreased since 1965 (Smith, et al, 2013). Children are rarely involved in food preparation in the home (Fulkerson, et al, 2008). -

Downloads of Technical Information

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Nuclear Spaces: Simulations of Nuclear Warfare in Film, by the Numbers, and on the Atomic Battlefield Donald J. Kinney Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES NUCLEAR SPACES: SIMULATIONS OF NUCLEAR WARFARE IN FILM, BY THE NUMBERS, AND ON THE ATOMIC BATTLEFIELD By DONALD J KINNEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Donald J. Kinney defended this dissertation on October 15, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Dissertation Joseph R. Hellweg University Representative Jonathan A. Grant Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member Guenter Kurt Piehler Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Morgan, Nala, Sebastian, Eliza, John, James, and Annette, who all took their turns on watch as I worked. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee, Kris Harper, Jonathan Grant, Kurt Piehler, and Joseph Hellweg. I would especially like to thank Ron Doel, without whom none of this would have been possible. It has been a very long road since that afternoon in Powell's City of Books, but Ron made certain that I did not despair. Thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................vii 1. -

Lexical Translation in Movies: a Comparative Analysis of Persian Dubs and Subtitles Through CDA

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 6, Issue 8, August 2018, PP 22-29 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0608003 www.arcjournals.org Lexical Translation in Movies: A comparative Analysis of Persian Dubs and Subtitles through CDA Saber Noie1*, Fariba Jafarpour2 Iran *Corresponding Author: Saber Noie, Iran Abstract: The impact of translated movies has already been emphasized by quiet a number of researchers. The present study aimed to investigate the strategies of the Iranian subtitlers and dubbers of English movies in rendering English words. To this aim, three theoretical frameworks were employed: The strategies proposed by Venuti, and Newmark's classification used first by researcher and then, researcher went back to the Van Dijk’s Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), in the part dominance. The aim was to find which strategies were the most prevalently used by Iranian subtitlers and dubbers and to see which model fitted these attempts the best. A movie was investigated: the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Through a qualitative content analysis, distribution of strategies was found and reported in frequencies and percentages. They were crossed – compared between the three frameworks. The result showed that which strategies of each model were used more. The results of this study may pave the way for future research in literary translation and help translation instructors and translation trainees as well in translation classes. Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis (Cda), Domestication, Dub, Foreignization, Subtitle 1. INTRODUCTION In the age of globalization, digitalization, and dominance of media, audiovisual translation (AVT) can play an increasingly important role in communication across cultures and languages. -

Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 281 487 fk 012 601 AUTHOR Shane, Harold G. TITLE Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87367-434-0 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 96p. AVAILABLE FROMPhi Delta Kappa, PO Box 789, Bloomington, IN 47402 ($4,00). puB TYPE Books (010) -- Information Analyses (070) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS_PRICE_ MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Change Strategies; Computers; *Computer Uses in Education; Curriculum Development; *Educational Change; Global Approach; Mass Media Effects; Robotics; *Science and Society; *Technological Advancement; Television Research IDENTIFIERS Learning Environment; *Microelectronics ABSTRACT General background information on microtechnologies with_ implications for educators provides an introduction to this review of past and current developments in microelectronics and specific ways in which the microchip is permeating society, creating problems and opportunities both in the workplace and the home. Topics discussed in the first of two major sections of this report include educational and industrial impacts of the computer and peripheral equipment, with particular attention to the use of computers in educational institutions and in an information society; theuse of robotics, a technology now being used in more than 2,000 schools and 1,200 colleges; the growing power of the media, particularly television; and the importance of educating young learners tocope with sex, violence, and bias in the media. The second section addresses issues created by microtechnologies since the first computer made its debut in 1946; redesigning the American educational system for a high-tech society; and developing curriculum appropriate for the microelectronic age, including computer applications and changes at all levels from early childhood education to programs for mature learners. -

The 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests in Chinese Fiction and Film

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Making the Censored Public: The 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests in Chinese Fiction and Film A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Thomas Chen Chen 2016 © Copyright by Thomas Chen Chen 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Making the Censored Public: The 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests in Chinese Fiction and Film by Thomas Chen Chen Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Kirstie M. McClure, Co-Chair Professor Robert Yee-Sin Chi, Co-Chair Initiated by Beijing college students, the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests—"Tiananmen"— shook all of China with their calls for democratic and social reforms. They were violently repressed by the Chinese state on June 4, 1989. Since then, their memory has been subject within the country to two kinds of censorship. First, a government campaign promulgating the official narrative of Tiananmen, while simultaneously forbidding all others, lasted into 1991. What followed was the surcease of Tiananmen propaganda and an expansion of silencing to nearly all mentions that has persisted to this day. My dissertation examines fiction and film that evoke Tiananmen from within mainland China and Hong Kong. It focuses on materials that are particularly open to a self-reflexive reading, such as literature in which the protagonists are writers and films shot without authorization that in their editing indicate the precarious ii circumstances of their making. These works act out the contestation between the state censorship of Tiananmen-related discourse on the one hand and its alternative imagination on the other, thereby opening up a discursive space, however fragile, for a Chinese audience to reconfigure a historical memory whose physical space is off limits. -

Wang, D., & Zhang, X. (2017). Fansubbing in China: Technology

Wang, D. , & Zhang, X. (2017). Fansubbing in China: Technology- facilitated activism in translation. Target. International Journal for Translation Studies, 29(2), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.29.2.06wan Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1075/target.29.2.06wan Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via John Benjamins at https://benjamins.com/online/target/articles/target.29.2.06wan . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Fansubbing in China: Technology-Facilitated Activism in Translation Dingkun Wang and Xiaochun Zhang Abstract This paper seeks to explore the socio-political tension between freedom and constraints in the Chinese fansubbing network. It views the development of fansubbing in China as a process of technology democratisation with the potential to liberate ordinary citizens from authoritarian and commercial imperatives, enabling them to contest official state domination. The paper draws on the strategies adopted by fansubbing groups to organise their working practices and interactive social activities with a view to engaging target audiences. Both facets complement each other and bring to the fore the ‘gamified’ system of fansubbing networks. Gamification enables ordinary citizens to translate, distribute and consume foreign audiovisual products in ways they consider appropriate, in a strategic move that opposes collective activism to government dominance. -

2015/2016 WGSA Council V

2015/2016 WGSA Council v Chairperson - Theoline Maphutha THEOLINE MAPHUTHA CHAIRPERSON Theoline Maphutha is a self-employed writer with over five years’ experience in the film and television industry. Before pursuing a career as a writer, she studied and worked in the information and communications technology (ICT) industry for almost 10 years as a support administrator, systems implementer, and project manager. Although skilled in lifestyle/magazine program writing, she’s a published poet, lyricist, and blogger, passionate about kaizen, constant self-improvement. Contribution is one of her highest values (ever since she was a Brownie in the girl scouts). Her life’s goal is to empower people to follow their purpose using the knowledge, experience, and resources available to her. Theoline is an independent soul with nimble flexibility, and a deliberate, succinct style of communication, who delivers autonomously creative ideas and solutions. Vice Chair - Peter Goldsmid PETER GOLDSMID LEGAL SERVICES Writer-director-producer Peter Goldsmid has a background in legal philosophy and politics and a keen interest in the interface between morality, justice, crime, social issues – and drama. This would his final year on Council where, if elected, he would continue to giving advice to writers in their dealings with producers. This includes advising on legal issues (such as contracts), helping writers access professional legal help if necessary, and mediating in disputes. Having worked both as producer and writer for hire, he has a balanced perspective on the issues that affect writers and brings this to bear in his contributions to Council. He is currently nominated for a 2015 writing SAFTA (as part of the “Traffic” writing team) and a Muse Award for documentary writing on Dance up from the street. -

TV News, Reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No

TV News Reporting and Production – MCM 516 VU TV News, reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No. Lesson 1 Creativity and idea generation for television 3 Lesson 2 Pre-requisites of a Creative Producer/Director 7 Lesson 3 Refining an idea for Production 10 Lesson 4 Concept Development 14 Lesson 5 Research and reviews 16 Lesson 6 Script Writing 18 Lesson 7 Pre-production phase 21 Lesson 8 Selection of required Content and talent 25 Lesson 9 Programme planning 29 Lesson 10 Production phase 35 Lesson 11 Camera Work 38 Lesson 12 Light and Audio 43 Lesson 13 Day of Recording/Production 52 Lesson 14 Linear editing and NLE 61 Lesson 15 Mixing and Uses of effects 64 Lesson 16 Selection of the News 69 Lesson 17 Writing of the News 72 Lesson 18 Editing of the News 75 Lesson 19 Compilation of News Bulletin 77 Lesson 20 Presentation of News Bulletin 80 Lesson 21 Making Special Bulletins 82 Lesson 22 Technical Codes, Terminology, and Production Grammar 84 Lesson 23 Types of TV Production 89 Lesson 24 Drama and Documentary 91 Lesson 25 Sources of TV News 93 Lesson 26 Functions of a Reporter 97 Lesson 27 Beats of Reporting 98 Lesson 28 Structure of News Department 99 Lesson 29 Electronic Field Production 101 Lesson 30 Live Transmissions 103 Lesson 31 Qualities of a news producer 108 Lesson 32 Duties of a news producer 111 Lesson 33 Assignment/News Editor 112 Lesson 34 Shooting a News film 114 Lesson 35 Preparation of special reports 117 Lesson 36 Interviews, vox pops and public opinions 121 Lesson 37 Back Ground voice and voice over -

Blockchain's Challenge for the Fourth Amendment

Transparency is the New Privacy: Blockchain’s Challenge for the Fourth Amendment Paul Belonick* 23 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 114 (2020) ABSTRACT Blockchain technology is now hitting the mainstream, and countless human interactions, legitimate and illegitimate, are being recorded permanently—and visibly— into distributed digital ledgers. Police surveillance of day-to-day transactions will never have been easier. Blockchain’s open, shared digital architecture thus challenges us to reassess two core premises of modern Fourth Amendment doctrine: that a “reasonable expectation of privacy” upholds the Amendment’s promise of a right to be “secure” against “unreasonable searches,” and that “a reasonable expectation of privacy” is tantamount to total secrecy. This article argues that these current doctrines rest on physical-world analogies that do not hold in blockchain’s unique digital space. Instead, blockchain can create security against “unreasonable searches,” even for data that are shared or public, because blockchain’s open distributed architecture does the work in digital space that privacy does in physical space to advance Fourth Amendment values such as security, control of information, free expression, and personal autonomy. The article also evaluates * Assistant Prof. of Practice and Director, Startup Legal Garage, Center for Innovation, UC Hastings Law School. University of Virginia, J.D. 2010, PhD. 2016. I would like to thank Robin Feldman, Darryl Brown, Ric Simmons, Jonathan Widmer-Rich, Andrew Crespo, David Roberts, and the participants of the CrimFest! 2019 conference for their advice and comments. Maximilien Pallu, Cyril Kottuppallil, and Katie Lindsay provided excellent research assistance. My wife provided much needed support. 114 Winter 2020 TRANSPARENCY IS THE NEW PRIVACY 115 textualist approaches to blockchain, concluding that the twenty-first century’s latest technology shows how the eighteenth-century text’s focus on ownership and control may be a better means to achieve fundamental human ends than privacy-as-secrecy. -

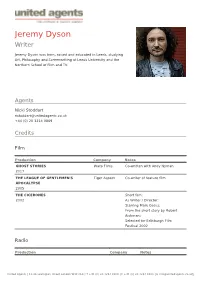

Jeremy Dyson Writer

Jeremy Dyson Writer Jeremy Dyson was born, raised and educated in Leeds, studying Art, Philosophy and Screenwriting at Leeds University and the Northern School of Film and TV. Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Film Production Company Notes GHOST STORIES Warp Films Co-written with Andy Nyman 2017 THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S Tiger Aspect Co-writer of feature film APOCALYPSE 2005 THE CICERONES Short film; 2002 As Writer / Director; Starring Mark Gatiss; From the short story by Robert Aickman; Selected for Edinburgh Film Festival 2002 Radio Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE UNSETTLED DUST: THE STRANGE STORIES BBC Radio 4 OF ROBERT AICKMAN 2011 RINGING THE CHANGES BBC Radio 4 Co-written with Mark 2000 Gatiss Adapted from the short story by Robert Aickman ON THE TOWN WITH THE LEAGUE OF BBC Radio 4 Co-writer GENTLEMEN Sony Silver Award 1997 Television Production Company Notes THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S BBC2 ANNIVERSARY SPECIALS 2017 TRACEY ULLMAN'S SHOW BBC1 2016 - 2017 PSYCHOBITCHES (SERIES 1 & 2) Tiger Aspect/Sky Arts Director/Co-writer 2012 - 2015 Nominated for two British Comedy Awards 2013; Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best TV Comedy THE ARMSTRONG & MILLER Hat Trick / BBC1 Series 1, 2 & 3 SHOW Script Editor/ Writer 2007 - 2010 BAFTA Award Best Comedy 2010 BILLY GOAT Hat Trick / BBC 1 x 60' 2008 Northern Ireland /BBC1 FUNLAND BBC2 Co-creator, co-writer and Associate 2006 -

Re-Thinking Liberal Free Speech Theory

THE SHAPE OF FREE SPEECH: RE-THINKING LIBERAL FREE SPEECH THEORY Anshuman A. Mondal, School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7RT, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]; Tel: +44 (0)1603 597655 Abstract: Noting the apparent inconsistency in attitudes towards free speech with respect to antisemitism and Islamophobia in western liberal democracies, this essay works through the problem of inconsistency within liberal free speech theory, arguing that this symptomatically reveals an aporia that exposes the inability of liberal free speech theory to account for the ways in which free speech actually operates in liberal social orders. Liberal free speech theory conceptualizes liberty as smooth, continuous, homogeneous, indivisible, and extendable without interruption until it reaches the outer limits. This makes it difficult for liberal free speech theory to account for restrictions that lie within those outer limits, and therefore for the ways in which restraints, restrictions and closures are always-already at work within the lived experience of liberty, for it is these – and the inconsistencies they give rise to – that give freedom its particular texture and timbre in any given social and cultural context. The essay concludes with an alternative ‘liquid’ theory of free speech, which accounts for the ‘shaping’ of liberty by social forces, culture and institutional practices. Keywords: free speech; freedom of expression; liberalism; John Stuart Mill; antisemitism; Islamophobia; liberty; liquidity