Script Development As a ‘Wicked Problem’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Dee, Mike (1996) Sun, sea, sex, sand and conservatism in the Australian television soap opera. Young People Now, March, pp. 1-5. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/62594/ c Copyright 1996 [please consult the author] This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Author’s final version of article for Young People Now (published March 1996) Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera In this issue, Mike Dee expands on his earlier piece about soap operas. -

The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema’, Review of Capital As Power, Vol

THE RISE OF A CONFIDENT HOLLYWOOD Suggested citation: James McMahon (2013), ‘The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema’, Review of Capital as Power, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 23-40. The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema1 JAMES MCMAHON Nature ceased to be inscrutable, subject to demonic incursions from another world: the very essence of Nature, as freshly conceived by the new scientists, was that its sequences were orderly and therefore predictable: even the path of a comet could be charted through the sky. It was on the model of this external physical order that men began systematically to reorganize their minds and their practical activities: this carried further, and into every department, the precepts and practices empirically fostered by bourgeois finance. Like Emerson, men felt that the universe itself was fulfilled and justified, when ships came and went with the regularity of heavenly bodies. - Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization he Hollywood film business, like any other business enterprise, operates according to the logic of capitalization. Capitalization in an instrumental logic T that is forward-looking in its orientation. Capitalization expresses the present value of an expected stream of future earnings. And since the earnings of the Hollywood film business depend on cinema and mass culture in general, we can say that the current fortunes of the Hollywood film business hinge on the future of cinema and mass culture. The ways in which pleasure is sublimated through mass culture, and how these ways may evolve in the future, have a bearing on the valuation of Hollywood’s control of filmmaking. -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Hyperreal Australia the Construction of Australia in Neighbours and Home & Away

Hyperreal Australia the construction of Australia in Neighbours and Home & Away Melissa McEwen March 2001 This volume is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the Australian National University in the Department of Australian Studies I wish to confirm that the thesis is my own work and that all sources used have been acknowledged. Melissa McEwen 30 March 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of authorship ii Table of contents iii Acknowledgments iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Neighbours 5 Employment 7 Education 10 E thnicity 12 W om en 14 Masculinity 18 Relationships and sexuality 20 Lifestyle 22 Disease and mental illness 25 C onclusion 26 3. Home & Away 27 Employment 30 Education 32 Ethnicity 34 W om en 37 Masculinity 42 Relationships and sexuality 45 Lifestyle 48 Disease and mental illness 49 Conclusion 51 4. National Stories 52 What is soap opera? 52 National myths and representation 56 Jobs and education 60 Ethnicity and racism 64 W om en 67 Masculinity 72 Relationships and sexuality 75 Lifestyles 77 Disease and mental illness 79 C onclusion 80 iii j. Constructing Australia 81 Construction and reception of soaps 81 Impact of television 88 Hyperreal Australia 92 Conclusion 107 i. A Moment’s Reflection 108 Mbliography 111 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As this thesis has been a long time in gestation, there are a number of people to thanks for their assistance and help: Jon McConachie for starting me down this path and John Docker for guiding me to the end; Ann Curthoys and Noel Purdon for helping to ensure -

2012 Conference Program

WEDNESDAY 1 IMAGINATION IS THE 21ST CENTURY TECHNOLOGY AUGUST 8-11, 2012 WELCOME Welcome to Columbia College Chicago and the 2012 University Film and Video Association Conference. We are very excited to have Peter Sims, author of Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge From Small Discoveries, as our keynote speaker. Peter’s presentation on the morning of Wednesday August 8 will set the context for the overall conference focus on creativity and imagination in film and video education. The numerous panel discussions and presentations of work to follow will summarize the current state of our field and offer opportunities to explore future directions. This year we have a high level of participation from vendors servicing our field who will present the latest technologies, products, and services that are central to how we teach everything from theory and critical studies to hands-on screen production. Of course, Chicago is one of the world’s greatest modern cities, and the Columbia College campus is ideally placed in the South Loop for access to Lake Michigan and Grant Park with easy connections to the music and theater venues for which the city is so well known. We hope you have a stimulating and enjoyable time at the 2012 Conference. Bruce Sheridan Professor & Chair, Film & Video Department Columbia College Chicago 2 WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY 3 WE WOULD LIKE TO THANK OUR GENEROUS COFFEE BREAKS FOR THE CONFERENCE WILL BE SPONSORS FOR THEIR SUPPORT OF UFVA 2012. HELD ON THE 8TH FLOOR AMONG THE EXHIBIT PLEASE BE SURE TO VISIT THEIR BOOTHS. BOOTHS AND HAVE BEEN GENEROUSLY SPONSORED BY ENTERTAINMENT PARTNERS. -

2015/2016 WGSA Council V

2015/2016 WGSA Council v Chairperson - Theoline Maphutha THEOLINE MAPHUTHA CHAIRPERSON Theoline Maphutha is a self-employed writer with over five years’ experience in the film and television industry. Before pursuing a career as a writer, she studied and worked in the information and communications technology (ICT) industry for almost 10 years as a support administrator, systems implementer, and project manager. Although skilled in lifestyle/magazine program writing, she’s a published poet, lyricist, and blogger, passionate about kaizen, constant self-improvement. Contribution is one of her highest values (ever since she was a Brownie in the girl scouts). Her life’s goal is to empower people to follow their purpose using the knowledge, experience, and resources available to her. Theoline is an independent soul with nimble flexibility, and a deliberate, succinct style of communication, who delivers autonomously creative ideas and solutions. Vice Chair - Peter Goldsmid PETER GOLDSMID LEGAL SERVICES Writer-director-producer Peter Goldsmid has a background in legal philosophy and politics and a keen interest in the interface between morality, justice, crime, social issues – and drama. This would his final year on Council where, if elected, he would continue to giving advice to writers in their dealings with producers. This includes advising on legal issues (such as contracts), helping writers access professional legal help if necessary, and mediating in disputes. Having worked both as producer and writer for hire, he has a balanced perspective on the issues that affect writers and brings this to bear in his contributions to Council. He is currently nominated for a 2015 writing SAFTA (as part of the “Traffic” writing team) and a Muse Award for documentary writing on Dance up from the street. -

TV News, Reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No

TV News Reporting and Production – MCM 516 VU TV News, reporting and Production MCM 516 Table of Contents Page No. Lesson 1 Creativity and idea generation for television 3 Lesson 2 Pre-requisites of a Creative Producer/Director 7 Lesson 3 Refining an idea for Production 10 Lesson 4 Concept Development 14 Lesson 5 Research and reviews 16 Lesson 6 Script Writing 18 Lesson 7 Pre-production phase 21 Lesson 8 Selection of required Content and talent 25 Lesson 9 Programme planning 29 Lesson 10 Production phase 35 Lesson 11 Camera Work 38 Lesson 12 Light and Audio 43 Lesson 13 Day of Recording/Production 52 Lesson 14 Linear editing and NLE 61 Lesson 15 Mixing and Uses of effects 64 Lesson 16 Selection of the News 69 Lesson 17 Writing of the News 72 Lesson 18 Editing of the News 75 Lesson 19 Compilation of News Bulletin 77 Lesson 20 Presentation of News Bulletin 80 Lesson 21 Making Special Bulletins 82 Lesson 22 Technical Codes, Terminology, and Production Grammar 84 Lesson 23 Types of TV Production 89 Lesson 24 Drama and Documentary 91 Lesson 25 Sources of TV News 93 Lesson 26 Functions of a Reporter 97 Lesson 27 Beats of Reporting 98 Lesson 28 Structure of News Department 99 Lesson 29 Electronic Field Production 101 Lesson 30 Live Transmissions 103 Lesson 31 Qualities of a news producer 108 Lesson 32 Duties of a news producer 111 Lesson 33 Assignment/News Editor 112 Lesson 34 Shooting a News film 114 Lesson 35 Preparation of special reports 117 Lesson 36 Interviews, vox pops and public opinions 121 Lesson 37 Back Ground voice and voice over -

V23N5 2012.Indd

Six men, two dories and the North Atlantic Why it’s an apt analogy for Atlantic Canada’s film industry and its place on the global stage. 52 | Atlantic Business Magazine | September/October 2012 By Stephen Kimber dawn in the nowhere It’s middle of the Atlantic ocean. How many days have they been drifting out here? Dickie – at 17, the youngest crew member – is supposed to be keeping watch. But he’s asleep, sprawled out in the bow of one of the two dories, his head lolling over the gunwhale. He wakes with a guilty start, stares, tries to make sense of the endless nothingness of dark-blue sea and flat grey sky. Wait! What’s that? On the horizon. A speck? Another vessel? A mirage? He looks back into his dory where his father, Merv, and Pete, the harpooner, are curled up asleep, and then across to the other dory where Gerald, Mannie and Gib are sleeping too. Finally, he decides. He reaches out, whispers, “Pete… Pete.” Pete wakes, growls: “What?” Dickie can only point. Pete sees what Dickie sees. He throws off his blanket, jumps to his feet. “There’s a boat,” he says, then louder, as if convincing himself. “There’s a boat. THERE’S A BOAT!” He’s screaming now, rousing the others. Gerald, the captain, immediately assumes command, scrambling to find the fog horn he’d rescued when their fishing boat sank. He blows a blast. Then another. The rest of the men grab for the oars. Mannie, the first mate, struggles to bring order to their chaos. -

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

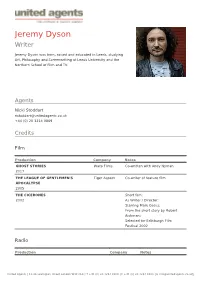

Jeremy Dyson Writer

Jeremy Dyson Writer Jeremy Dyson was born, raised and educated in Leeds, studying Art, Philosophy and Screenwriting at Leeds University and the Northern School of Film and TV. Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Film Production Company Notes GHOST STORIES Warp Films Co-written with Andy Nyman 2017 THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S Tiger Aspect Co-writer of feature film APOCALYPSE 2005 THE CICERONES Short film; 2002 As Writer / Director; Starring Mark Gatiss; From the short story by Robert Aickman; Selected for Edinburgh Film Festival 2002 Radio Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE UNSETTLED DUST: THE STRANGE STORIES BBC Radio 4 OF ROBERT AICKMAN 2011 RINGING THE CHANGES BBC Radio 4 Co-written with Mark 2000 Gatiss Adapted from the short story by Robert Aickman ON THE TOWN WITH THE LEAGUE OF BBC Radio 4 Co-writer GENTLEMEN Sony Silver Award 1997 Television Production Company Notes THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN'S BBC2 ANNIVERSARY SPECIALS 2017 TRACEY ULLMAN'S SHOW BBC1 2016 - 2017 PSYCHOBITCHES (SERIES 1 & 2) Tiger Aspect/Sky Arts Director/Co-writer 2012 - 2015 Nominated for two British Comedy Awards 2013; Winner of the Rose d'Or for Best TV Comedy THE ARMSTRONG & MILLER Hat Trick / BBC1 Series 1, 2 & 3 SHOW Script Editor/ Writer 2007 - 2010 BAFTA Award Best Comedy 2010 BILLY GOAT Hat Trick / BBC 1 x 60' 2008 Northern Ireland /BBC1 FUNLAND BBC2 Co-creator, co-writer and Associate 2006 -

The Secrets to Creating an Indie Game Franchise

The Secrets to Creating an Indie Game Franchise Christy Dena Writer-Designer-Director Universe Creation 101 Welcome everyone. I’m Christy Dena and I’ll be talking about “The Secrets to Creating an Indie Game Franchise”. But why are these secrets? Why aren’t the techniques to develop a franchise common knowledge? Why aren’t we all learning how to do this as part of our craft? You may be thinking, Christy, it’s about money. Franchises are about exploiting revenue streams. But that is the business etymology, the historical origins of the term franchise that kicked in 16th century onwards. But for us here at the Narrative Summit, as writers, as designers, we have the problem of crafting multiple artforms into a whole experience: games, films, books, soundtracks, whatever. Why isn’t this skill common knowledge? It’s because there is a lot of resistance to making in multiple artforms. I know, I’ve been battling these resistances for 20 years. You’ve heard of the 10,000 hour rule, well the idea that has stuck with people is this: if you hope to be any good at anything, you need to work at one thing for a very long time. If you don’t, you’re a “Jack of all Trades and Master of None”. So we all believe that working in multiple artforms dilutes or corrupts your creative development rather than enhancing it. “Not Us” - It’s the belief that each artform is substantially different, and so it is not what “we” do. Writers don’t talk about media. -

I Liked It, Didn't Love It (Screenplay Development

12 “I Thought Movies Just Got Made!” 1 defining development DEVELOPMENT: The act of developing. The state of being developed. A significant event, occurrence, or change. Determination of the best techniques for applying a new device or process to production of goods or services. As in music: Elaboration of a theme with rhythmic and harmonic variations. The central section of a movement in sonata form, in which the theme is elaborated and explored. PROCESS: A series of actions, changes, or functions bringing about a result: the process of digestion; A series of operations performed in the making or treatment of a product: a manufacturing process; leather dyed during the tanning process. Progress; passage: the process of time; events now in process. DEVELOPMENT PROCESS: Hell Most people in the motion picture industry know what development is, but few truly understand the process of development. Most hate it, as it can be long and arduous—years and years may go by, drafts replace other drafts of the same screenplay, writers come and go; talent is attached, falls out, and is then re-attached; projects get placed into turnaround, languish for years, get picked up again and fast-tracked, and, sometimes—if you’re lucky—your project is developed to the point where it gets the coveted greenlight. That is what every producer, director, writer, or development executive hopes for— to see the movie they’ve labored over for years become a reality on celluloid. Over 80 percent of the scripts in development at the studios are waiting to see the light of day.