Hliebing Dissertation Revised 05092012 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finn Ballard: No Trespassing: the Post-Millennial

Page 15 No Trespassing: The postmillennial roadhorror movie Finn Ballard Since the turn of the century, there has been released throughout America and Europe a spate of films unified by the same basic plotline: a group of teenagers go roadtripping into the wilderness, and are summarily slaughtered by locals. These films may collectively be termed ‘roadhorror’, due to their blurring of the aesthetic of the road movie with the tension and gore of horror cinema. The thematic of this subgenre has long been established in fiction; from the earliest oral lore, there has been evident a preoccupation with the potential terror of inadvertently trespassing into a hostile environment. This was a particular concern of the folkloric Warnmärchen or ‘warning tale’ of medieval Europe, which educated both children and adults of the dangers of straying into the wilderness. Pioneers carried such tales to the fledging United States, but in a nation conceptualised by progress, by the shining of light upon darkness and the pushing back of frontiers, the fear of the wilderness was diminished in impact. In more recent history, the development of the automobile consolidated the joint American traditions of mobility and discovery, as the leisure activity of the road trip became popular. The wilderness therefore became a source of fascination rather than fear, and the road trip became a transcendental voyage of discovery and of escape from the urban, made fashionable by writers such as Jack Kerouac and by those filmmakers such as Dennis Hopper ( Easy Rider, 1969) who influenced the evolution of the American road movie. -

DP Ce Que Le Jour Doit a La Nuit Mise En Page 1

DP Ce que le jour doit à la nuit_Mise en page 1 26/06/12 10:48 Page2 ALEXANDRE FILMS Présente UN FILM DE ALEXANDRE ARCADY CRÉDITS PHOTOS : © ETIENNE GEORGE. CRÉDITS PHOTOS : DP Ce que le jour doit à la nuit_Mise en page 1 26/06/12 10:48 Page4 ALEXANDRE FILMS présente Un film d’ALEXANDRE ARCADY D’après le best-seller de YASMINA KHADRA Avec NORA ARNEZEDER, FU’AD AÏT AATTOU, ANNE PARILLAUD, VINCENT PEREZ, ANNE CONSIGNY, FELLAG, NICOLAS GIRAUD, OLIVIER BARTHÉLÉMY Sortie : 12 SEPTEMBRE Durée : 2h39 / Image : Scope / Son : Dolby digital DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE WILD BUNCH DISTRIBUTION BCG PRESSE 99, rue de la Verrerie – 75004 Paris 23, rue Malar Tél. : 01 53 10 42 50 75007 Paris [email protected] Tél. : 01 45 51 13 00 www.wildbunch-distribution.com [email protected] Les photos et le dossier de presse sont téléchargeables sur le site du film www.cequelejourdoitalanuit.com/presse DP Ce que le jour doit à la nuit_Mise en page 1 26/06/12 10:48 Page6 Synopsis Algérie, années 1930. Younes a 9 ans lorsqu’il est confié à son oncle pharmacien à Oran. Rebaptisé Jonas, il grandit parmi les jeunes de Rio Salado dont il devient l’ami. Dans la bande, il y a Emilie, la fille dont tous sont amoureux. Entre Jonas et elle naîtra une grande histoire d’amour, qui sera bientôt troublée par les conflits qui agitent le pays. DP Ce que le jour doit à la nuit_Mise en page 1 26/06/12 10:48 Page7 Alexandre Arcady - Yasmina Khadra Entretien croisé Alexandre Arcady, comment avez-vous découvert le livre de Yasmina Khadra et qu’est-ce qui vous a donné envie de l’adapter ? Alexandre Arcady – C’est en vacances à l’étranger il y a déjà maintenant trois ans, que j’ai eu connaissance du roman de Yasmina Khadra Ce que le jour doit à la nuit en lisant une critique dans un journal. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

Catalogue-2018 Web W Covers.Pdf

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE 22 years in Hollywood… The COLCOA French Film this year. The French NeWave 2.0 lineup on Saturday is Festival has become a reference for many and a composed of first films written and directed by women. landmark with a non-stop growing popularity year after The Focus on a Filmmaker day will be offered to writer, year. This longevity has several reasons: the continued director, actor Mélanie Laurent and one of our panels will support of its creator, the Franco-American Cultural address the role of women in the French film industry. Fund (a unique partnership between DGA, MPA, SACEM and WGA West); the faithfulness of our audience and The future is also about new talent highlighted at sponsors; the interest of professionals (American and the festival. A large number of filmmakers invited to French filmmakers, distributors, producers, agents, COLCOA this year are newcomers. The popular compe- journalists); our unique location – the Directors Guild of tition dedicated to short films is back with a record 23 America in Hollywood – and, of course, the involvement films selected, and first films represent a significant part of a dedicated team. of the cinema selection. As in 2017, you will also be able to discover the work of new talent through our Television, Now, because of the continuing digital (r)evolution in Digital Series and Virtual Reality selections. the film and television series industry, the life of a film or series depends on people who spread the word and The future is, ultimately, about a new generation of foreign create a buzz. -

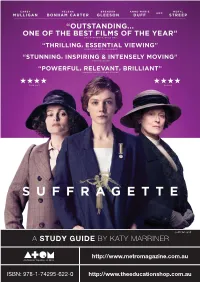

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Fatou N Diaye Nue

Fatou n diaye nue Continue Home explores Encyclopedia sugar-free mooncakes no sugar 2020 teacher heat report user lgdbaike F'Y201310 also 12138super_ (All 0 photos uploaded) More than 2 collaborations with people film... (All) Edit Lock Talk Download Video This term lacks review chart, complements the appropriate content to make the term more complete, can also be quickly updated, hurry to edit it! 1 Highlights of ▪ Film Works ▪ Series 2 Character Relationships Fatu N'Diaye Film Productions Play-time playwright starring Liz Francois Duperonlav Amoso, Firichid Ewash Actor 2006 Kigali Sunday Gentile Favreaux Luc Piccard, Fat Nou'Diaye Actor 206 Ka La David Gleeson Eric Aberanani, James Flynn Actor 2003 Fabu Daniel Vega Fatu N'Diaye, Diukunda Coma Actor 2002 Beautiful Singing VitaFlora Gomez Fatou N'Diaye, Ingelo Torres Actor 2002 Beautiful New World II Mission queen Exlibris Alan Shamonica Bellucci, Alan Chaba Actor 2001 Hope Fatu Daniel Vega Fatou N'Diaye, Pauline Fodouop Actor Transformer Une Bacchus Christopher Honore Amira Aquily, S'Bastien Hirel Actor Fatou Ntou'Diaye Serial Premiere Time Dramatic Director Starring in 2010 Bordel Pauline (8 episodes, 2013) Marbrook El Mejiana Chalier, Valerie Carsenti Actor Co-production Character Name Collaboration more than doubled Daniel Vega Daniel Vigne (2) : Hope in Law, Pascal N'Sonzi in Hope (2): Hope in Law, Hope in Co-Production (2): Hope in Law.By David Kundama Kaba Co-production (2): Hope Of Law, Claude Rich's Hope Claude Rich (2): Self-Help, Mission of the Beautiful New World II, Alan Sheba Alain Chabat (1): Mission Beautiful New World Reference II. -

Finding Neverland

BARRIE AND THE BOYS 0. BARRIE AND THE BOYS - Story Preface 1. J.M. BARRIE - EARLY LIFE 2. MARY ANSELL BARRIE 3. SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES 4. PETER PAN IS BORN 5. OPENING NIGHT 6. TRAGEDY STRIKES 7. BARRIE AND THE BOYS 8. CHARLES FROHMAN 9. SCENES FROM LIFE 10. THE REST OF THE STORY Barrie and the Llewelyn-Davies boys visited Scourie Lodge, Sutherland—in northwestern Scotland—during August of 1911. In this group image we see Barrie with four of the boys together with their hostess. In the back row: George Llewelyn Davies (age 18), the Duchess of Sutherland and Peter Llewelyn Davies (age 14). In the front row: Nico Llewelyn Davies (age 7), J. M. Barrie (age 51) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (age 11). Online via Andrew Birkin and his J.M. Barrie website. After their mother's death, the five Llewelyn-Davies boys were alone. Who would take them in? Be a parent to them? Provide for their financial needs? Neither side of the family was really able to help. In 1976, Nico recalled the relief with which his uncles and aunts greeted Barrie's offer of assistance: ...none of them [the children's uncles and aunts] could really do anything approaching the amount that this little Scots wizard could do round the corner. He'd got more money than any of us and he's an awfully nice little man. He's a kind man. They all liked him a good deal. And he quite clearly had adored both my father and mother and was very fond of us boys. -

GATTACA Written and Directed by Andrew Niccol ABOUT THE

Article on Gattaca by Mark Freeman Area of Study 1 & 2 Theme: Future worlds GATTACA Written and directed by Andrew Niccol Article by Mark Freeman ABOUT THE DIRECTOR Andrew Niccol, a screenwriter and director, was born in New Zealand and moved to England at the age of 21 to direct commercials. He has written and directed Gattaca, Simone and Lord of War as well as earning an Academy Award nomination for his screenplay for The Truman Show. OVERVIEW In recent years, scientific research has unearthed a greater understanding of our genetic make-up – the lottery that determines our appearance and physical capabilities. The means by which we inherit specific traits from our parents, our genes are like a blueprint of our future, determining our predisposition for specific talents or particular illnesses. Concurrent with this understanding of genetics have come successful attempts in cloning, and, more recently, the ethical debate over stem cell research to combat a range of physical maladies. Identification and eradication of rogue genes (those that could ultimately cause malfunction at birth or later in a person’s life) is a very real possibility with the developing exploration in genetic research. In your own DNA, you already carry the genetic code which will cause your physical development in your teens, your predisposition to weight gain in your twenties, your hair loss in your thirties, early menopause in your forties, the arthritis you develop in your fifties, your death from cancer in your seventies. It’s an imposing thought to consider the map of our histories, our futures, in terms of our genetic code. -

Rassegna Stampa

Rassegna stampa 12 aprile 2016 La proprietà intellettuale degli articoli è delle fonti (quotidiani o altro) specificate all'inizio degli stessi; ogni riproduzione totale o parziale del loro contenuto per fini che esulano da un utilizzo di Rassegna Stampa è compiuta sotto la responsabilità di chi la esegue; MIMESI s.r.l. declina ogni responsabilità derivante da un uso improprio dello strumento o comunque non conforme a quanto specificato nei contratti di adesione al servizio. INDICE ANICA - ANICA CITAZIONI 12/04/2016 La Repubblica - Roma 7 Tutti i film più belli al costo di tre euro solo per 4 giorni 12/04/2016 La Repubblica - Palermo 8 I film costano 3 euro con "Cinemadays" 12/04/2016 La Stampa - Torino 9 La festa del grande schermo Tre giorni di film a 3 euro 12/04/2016 QN - La Nazione - Lucca 10 Tutti al cinema Giornate speciali con ingresso a 3 euro 11/04/2016 Key4Biz 11 'Sostenere le sale per rilanciare il cinema'. Intervista a Carlo Bernaschi (ANEM) 11/04/2016 Panorama.it 13 I 10 film più visti della settimana ANICA - CINEMA 12/04/2016 Corriere della Sera - Nazionale 16 Selfie e candid camera per Hitler risorto 12/04/2016 La Repubblica - Nazionale 17 Toni Servillo in saio nelle stanze segrete del Potere tiranno 12/04/2016 La Stampa - Nazionale 18 Toni Servillo, San Francesco al tempo dei potenti e del G8 12/04/2016 La Stampa - Nazionale 19 "Il bello attraversa le epoche rimanendo fedele a se stesso" 12/04/2016 Il Messaggero - Nazionale 21 Un monaco nella stanza dei bottoni 12/04/2016 ItaliaOggi 23 Il mobile si racconta col cinema -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Archive Name ATAS14_Corp_140003273 MECH SIZE 100% PRINT SIZE Description ATAS Annual Report 2014 Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Posting Date May 2014 Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Unit # Live: 7.5” x 10” LIve: 7.5” x 10” message from THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER At the end of 2013, as I reflected on my first term as Television Academy chairman and prepared to begin my second, it was hard to believe that two years had passed. It seemed more like two months. At times, even two weeks. Why? Because even though I have worked in TV for more than three decades, I have never seen our industry undergo such extraordinary — and extraordinarily exciting — changes as it has in recent years. Everywhere you turn, the vanguard is disrupting the old guard with an astonishing new technology, an amazing new show, an inspired new way to structure a business deal. This is not to imply that the more established segments of our industry have been pushed aside. On the contrary, the broadcast and cable networks continue to produce terrific work that is heralded by critics and rewarded each year at the Emmys. And broadcast networks still command the largest viewing audience across all of their platforms. With our medium thriving as never before, this is a great time to work in television, and a great time to be part of the Television Academy. Consider the 65th Emmy Awards. The CBS telecast, hosted by the always-entertaining Neil Patrick Harris, drew our largest audience since 2005.