Hyperreal Australia the Construction of Australia in Neighbours and Home & Away

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Dee, Mike (1996) Sun, sea, sex, sand and conservatism in the Australian television soap opera. Young People Now, March, pp. 1-5. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/62594/ c Copyright 1996 [please consult the author] This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Author’s final version of article for Young People Now (published March 1996) Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera In this issue, Mike Dee expands on his earlier piece about soap operas. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Annie & Jack by Rachel

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Annie & Jack by Rachel Lyons Annie & Jack by Rachel Lyons. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6596ebb57e89c410 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. About us. Years later, I went to Baylor graduating with an Interior Design degree and Brent graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point as an officer. By God’s grace, I married that boy of my dreams and became a military wife and later mom of two children. Both of our children are adopted, just like their mom. Between military and corporate moves we were moving about every two or three years until we landed back in Texas and fell in love with Celina. Opening ANNIE JACK on Celina’s square in March of 2016 meant putting down roots and becoming part of the community. We are a lifestyle boutique offering a mix of home, fashion, and local artisanry. -

Crash Magazine

CRUCIAL SINCLAIR SPECTRUM ACTION! A— ZX SPECTRUM ABANDON SHIP! IT'S ZEPPELIN'S EXCLUSIVE Demo and Review * •w 100% • f « COLOUR! 'IP 100% A J? * SPECTRUM! * #v b Jfr * 100% • JUP BRILLIANCE1. • v kJ* V in . N > On your CRASH k / H if * - • V Powertape! -T^* 1 J ^ I A TWO COMPLETE GAMES! p, % -- ' • I iVik (T* BOUNCES EXCLUSIVE! ^ Denton Designs niln P SPY V SPY 3 SB Software Business REVIEW^. a. • . > W An Exclusive Demo — \ / f ' TITANIC BLINKY PLUS Jf Zeppelin WWF, ROD-LAND, SPACE fa' V ' PLUS CRUSADE, LOONEY TUNES, // DOUBLE DRAGON III, / t • N POKE ZONE % Playing Tips on cassette BIG NOSE, CISCO HEAT, ^ ' V , ?}/ i/Tr j PITFIGHTER Tjf /1 / ' Eek! Where's me ' j- A>\r I'll J f i''' % fab cassette?! INSIDE! FINAL PART OF * / ^ Ask your newsagent! A FAB 1992 CALENDAR M * / I POSTER TO COLLECT**,, * . a V / Y ' . y ' X- f 'V* ~ ^ - ^LiOGMe^T LiiVd 'a j cAPacowiidl All MGHI j fit ,l $ All filGHIS Pf'Jjr/f OCEAN SOFTWARE LIMITED • 6 CENTRA' TELEPHONE; 061 832 6*33 3 o MA1+ tt I ° < m i i n FS ^^^CifTnj r'lT/ili^ > ® K 1 • j • ^^ (SrrrD>3 ^^ / i\i i \ v.. o. 1 _ - -lift . • /V Vi .vr f«tl . -J I'l 'IKMni'rlirllNil Here you go, all — the second part of our fantastlco double sided poster-calendar, brought to you courtesy of the wonderfully mega-brill talents of Oliver Frey (autographs by appointment only). Unless you're a complete drongo, you'll have saved the other half of the poster from last month's Issue. -

IC Lacks British Minorities Are

Start the year making the right film choices - Felix’s films of the year pages 6&7 Disc Doctors get a bird’s eye view of London Naked Centrefold Jamie Oliver’s New Travel Section: Kuwait Fifteen Page 14 page 8 FREE No 1339 Thursday 12 JANUARY 2006 The student newspaper of Imperial College felixonline.co.uk felix Sports centre delayed New year’s resolution to get fit? Think again! missioning systems”. ally planned. However, the squash Rupert Neate Students and staff were only given courts have suffered more serious Editor three days notice of the postpone- problems and are not expected to ment in a college-wide email sent on open until mid-February. Friday 6 January. It seems bizarre A quick tour of the facility reveals The opening of Imperial’s new that students weren’t given more a considerable amount of work still Ethos sports centre has been hit by than one working day’s notice if needing to be completed. It’s hard to further delays. The centre, which there are three weeks worth of imagine how the centre could ever will be largely free for all students building work to be completed. have opened early this week. Even and staff, was originally scheduled Sameena Misbahuddin, Union the pavement outside has yet to be to open in October 2005. Last spring, President, described the delay as laid. Steve Howe, Assistant Director the Rector himself assured students “annoying, especially for students of Estates, said “the pavement is and staff that the new centre would who’ve cancelled their gym member- not essential for opening, and is the open on time and would not be sub- ships ready for the opening.. -

25 Years of Eastenders – but Who Is the Best Loved Character? Submitted By: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010

25 years of Eastenders – but who is the best loved character? Submitted by: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010 More than 2,300 members of the public were asked to vote for the Eastenders character they’d most like to share a takeaway with – with Alfie Moon, played by actor Shane Ritchie, topping the list of most loved characters. Janine Butcher is the most hated character from the last 25 years, with three quarters of the public admitting they disliked her. Friday marks the 25th anniversary of popular British soap Eastenders, with a half hour live special episode. To commemorate the occasion, the UK’s leading takeaway website www.Just-Eat.co.uk (http://www.just-eat.co.uk) asked 2,310 members of the public to list the character they’d most like to ‘have a takeaway with’, in the style of the age old ‘who would you invite to a dinner party’ question. When asked the multi-answer question, “Which Eastenders characters from the last 25 years would you most like to share a takeaway meal with?’, Shane Richie’s Alfie Moon, who first appeared in 2002 topped the poll with 42% of votes. The study was entirely hypothetical, and as such included characters which may no longer be alive. Wellard, primarily owned by Robbie Jackson and Gus Smith was introduced to the show in 1994, and ranked as the 5th most popular character to share a takeaway with. 1.Alfie Moon – 42% 2.Kat Slater – 36% 3.Nigel Bates – 34% 4.Grant Mitchell – 33% 5.Wellard the Dog – 30% 6.Peggy Mitchell – 29% 7.Arthur Fowler – 26% 8.Dot Cotton – 25% 9.Ethyl Skinner – 22% 10.Pat Butcher – 20% The poll also asked respondents to list the characters they loved to hate, with Janine Butcher, who has been portrayed by Rebecca Michael, Alexia Demetriou and most recently Charlie Brooks topping the list of the soaps most hated, with nearly three quarters of the public saying listing her as their least favourite character. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

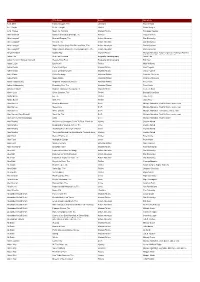

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Announcement

Announcement Total 100 articles, created at 2016-04-26 06:03 1 AdWeek : All News - powered by FeedBurner Since CBS This Morning debuted in 2012, it's enjoyed steady gains for the network in the daypart. It's the fastest-growing... 2016-04-25 23:50 30KB feeds.adweek.com (7.03/8) 2 Hungarian weatherman fired after fart-filled wind forecast BUDAPEST, Hungary — A Hungarian TV weatherman has been fired after giving a windy forecast some oomph with a range of fart sound effects. Szilard Horvath used recorded (3.00/8) bottom noises to 2016-04-26 06:02 1KB newsinfo.inquirer.net 3 Bottled water infects over 4,000 people in Spain with norovirus (2.00/8) BARCELONA, Spain — More than 4,000 people fell ill with norovirus in northeastern Spain after drinking bottled spring water contaminated with human fecal matter, local health officials said 2016-04-26 06:02 2KB newsinfo.inquirer.net 4 Obama sends more Special Forces to Syria in fight against IS (2.00/8) By Roberta Rampton HANOVER, Germany, April 25 (Reuters) - President Barack Obama announced on Monday the biggest expansion of U. S. ground troops in Syria sin... 2016-04-26 01:39 9KB www.dailymail.co.uk 5 Still swimming in exile, Syrian refugee to carry Rio flame ATHENS, Greece — As a swimming-mad teenager in Syria, Ibrahim Al-Hussein was glued to his TV set for the 2004 Athens Olympics. Twelve years later in Athens, and now a war refugee who is 2016-04-26 06:02 4KB sports.inquirer.net 6 US flies F-22s to Romania as show of strength to Russia CONSTANTA, Romania — The US Air Force on Monday flew in two F-22 Raptor fighter jets to Romania as a show of strength to deter Russian intervention in Ukraine. -

Student Newspaper October 11 1996

.,. sweet revival free before 10:31 rJr f2.50 after with this ) .-arling & two dogs fia bott. - mdayr A. nar, - STIJDENIncorporating juice magazine Britain's biggest weekly student newspaper October 11 1996 , -1 A Major 144 liiP;1exclusive Your chance to interview W‘'1 the Prime Minister Ulm)11Aan Thriller; ElOn tallcs)o juice alioul his jieW wyrh violenue ip the moms - u6es 4 Turn lo patie PLUS: SUN RISING, DAVID ADAM, PAIN BANKS INTERVIEWED AND FULL SEVEN-DAY TV LISTINGS GUIDE STUDENT aiming for the double COUNCIL FEARS Br A,u KAU( NAT It INAL _judges ha% e voted Leeds Student one of the hest student -newspapers in the country, Leeds Student has been shurtlisted for the Newspaper the Year prize in the annual student media awards_ hosted by the NUS and The HOUSING HELL Guardian Nine other papers are also up for the award- TwTwo Leeds Student contributors have also been Landlords under nominated for the individual Student Journalist of the Year award. Catriona Davies and Rosa Prince are aiming four others who,hope to win. fire over lethal "les an amazing surprise:' said Catriona. a former News Editor on the paper. "1 didn't expect anything like this accommodation when 1 sent in niy entry." By ANDY KELK Prestigious The results will he TWO-THIRDS of the houses announced at a prestigious ceremony on October 26 rented to students in Leeds are during the NUS Student Media conference. The dangerous and unfit to live in. Judging panel is made up of Sixty-seven per cent of the 8,500 media professionals, including Diana Madill Or student rental properties in the city 13130 Radio 5 Live, Rosie have been condemned as substandard Boycott. -

Read Varges Money Talks Epub For

Sean Bridges first appeared on March 20, 2001, [5]. Alex arrived in Genoa City to work on an important case for Newman Enterprises and the firm's boss Victor Newman was immediately impressed by the way she was doing business. She was working together with Neil Winters and the attraction between them was high even though they were constantly fighting. Olivia Winters helped Alex win the case however, the two were never friends because Olivia was constantly afraid of losing Neil to Alex. portrayed by Christopher Douglas. He would later become a prominent boyfriend of both Phyllis Summers and Jill Abbott. In July 2001, it was announced that Douglas had been let go from the role, and that it would be recast. [6]. List of The Young and the Restless characters (2000s). He later became the fiancé of Olivia Winters after being involved with her sister, Drucilla. He was portrayed by Ben Watkins. [27]. Anita was portrayed by Mitzi Kapture, and Frederick by John Martin. They were last seen on February 22, +91-22-25116741 2005. [25]. Ralph Hunnicutt first appeared on December 7, 2001, as the ex-husband of [email protected] Amanda Browning, [19]. Prior to her debut, the character was only known as "Erin". [2]. —Douglas on his firing from the soap opera (2001). Portrayed by Angelo Tiffe (2001– 02) Daniel Quinn (2002). To keep Wesley out of his way of getting back with Dru, Neil asked Dru's sister, Olivia, to keep Wesley busy. Wesley started to realize the extent of Dru's feelings for Neil by the end of the year when she changed her mind about spending the holidays with Wesley in Paris. -

How Fremantlemedia Australia's Daily Soap Won the Hearts of Millions Of

week 12 / 19 March 2015 AN AUSTRALIAN ICON How FremantleMedia Australia’s daily soap won the hearts of millions of viewers over three decades Luxembourg Luxembourg Croatia Guillaume de Posch RTL Group named RTL Hrvatska delivers keynote speech ‘Luxembourg’s launches three at the Cable Congress most attractive new pay channels Employer’ week 12 / 19 March 2015 AN AUSTRALIAN ICON How FremantleMedia Australia’s daily soap won the hearts of millions of viewers over three decades Luxembourg Luxembourg Croatia Guillaume de Posch RTL Group named RTL Hrvatska delivers keynote speech ‘Luxembourg’s launches three at the Cable Congress most attractive new pay channels Employer’ Cover Neighbours 30 years Publisher RTL Group 45, Bd Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg Editor, Design, Production RTL Group Corporate Communications & Marketing k before y hin ou T p r in t backstage.rtlgroup.com backstage.rtlgroup.fr backstage.rtlgroup.de QUICK VIEW “We have the content; you have the distribution pipeline” RTL Group “One of the most iconic p.10–11 programmes ever to be produced in Australia” RTL Group once FremantleMedia Australia again ‘Luxembourg’s p.4–9 Most Attractive Employer’ RTL Group p.12 Crime, Passion and Living enrich RTL Group’s family of channels in Croatia RTL Hrvatska p.13 An enriched listening experience, thanks to Big Picture ‘Shazam for Radio’ p.15 IP France p.14 SHORT NEWS p.16–17 PEOPLE p.18 “ONE OF THE MOST On 18 March 2015, the FremantleMedia Australia (FMA) production ICONIC PROGRAMMES Neighbours turned 30. Backstage looks back EVER TO BE PRODUCED at the success of this long-running soap. -

Greenville, MS 38702-1873 with Your Continued Service to Those in Need, Especially the Children

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF JUNIOR AUXILIARIES, INC. 845 South Main Street Greenville, Mississippi 38701 Mailing Address: Post Office Box 1873 Greenville, Mississippi 38702-1873 Telephone: (662) 332-3000 Facsimile: (662) 332-3076 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: www.najanet.org Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NAJAinc Follow us on Twitter: najainc Pinterest: http://pinterest.com/najainc/ LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/groups/National-Association-Junior-Auxiliaries-Inc-4502392 The Junior Auxiliary membership list provided in this Bulletin is for the use of the Junior Auxiliary only and cannot be used for promotion of any activity unrelated to the Junior Auxiliary. “The Junior Auxiliary membership list shall not be made available for commercial purposes or for the purpose of solicitation.” Association Standing Rules I. Association. C. Fund Raising and Contributions. Junior Auxiliary Prayer Send us, O God, as Thy messengers to the hearts without a home, to lives without love, to the crowds without a guide. Send us to the children whom none have blessed, to the famished whom none have visited, to the fallen whom none have lifted, to the bereaved whom none have comforted. Kindle Thy flame on the altars of our hearts, that others may be warmed thereby; cause Thy light to shine in our souls, that others may see the way; keep our sympathies and insight ready, our wills keen, our hands quick to help others in their need. Grant us clear vision, true judgment, with great daring as we seek to right the wrong; and so endow us with cheer- ful love that we may minister to the suffering and forlorn even as Thou wouldst. -

Superman's Origin Story < Donald Sutherland As

3-month TV calendar Page 29 RETURNING FAVORITES WESTWORLD ELEMENTARY QUANTICO THE AMERICANS NEW GIRL She’s back. Still fearless. And still very, very funny! MUST-SEE NEW SHOWS MARCH 19–APRIL 1, 2018 Superman’s origin story DOUBLE ISSUE < Donald Sutherland as the world’s richest man Grey’s Anatomy spinoff DOUBLE ISSUE • 2 WEEKS OF LISTINGS VOLUME 66 | NUMBER 12 | ISSUE #3427–3428 In This Issue On the Cover 18 Cover Story: Roseanne The iconic family comedy is back! We check in to see what’s next for the Conner clan in ABC’s much-anticipated reboot. 22 Spring Preview Donald Sutherland stars in FX’s Trust, Zach Braff returns with Alex, Inc., Superman’s history is told in Krypton, inside Grey’s Anatomy spinoff Station 19 (Jason George, inset) and Sandra Oh faces danger in Killing Eve. Plus: Intel on Westworld, The Americans, Quantico, Elementary, The Handmaid’s Tale and New Girl. 29 Spring TV Calendar 2 Ask Matt EDITOR’S 3 Stu We Love 4 Burning Questions LETTER Yikes! What really happened on that It’s been three decades since we met the shocking Bachelor finale. 5 Ratings Conners, a working-class family from fictional Lanford, Illinois, headed up by parents Rose- 6 Crime Scene NEW! anne, a factory line worker, and Dan, a contrac- Five can’t-miss specials and shows for true-crime fans. tor. Few shows since the ’70s had focused on 8 Tastemakers characters struggling with the money prob- Valerie Bertinelli dishes on her Food Network show. Plus: Her savory lems that come with blue-collar jobs.