Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

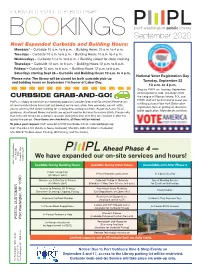

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

Read the Full Report As an Adobe Acrobat

CREATING A PUBLIC SQUARE IN A CHALLENGING MEDIA AGE A White Paper on the Knight Commission Report on Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in the Digital Age Norman J. Ornstein with John C. Fortier and Jennifer Marsico Executive Summary Much has changed in media and communications costs. Newspapers would benefit from looser technologies over the past fifty years. Today we face the rules and more flexibility. News organizations dual problems of an increasing gap in access to these should be able to work together to collect technologies between the “haves” and “have nots” and payment for content access. fragmentation of the once-common set of facts that 2. Implement government subsidies. With high Americans shared through similar experiences with the costs of operation, the newspaper industry media. This white paper lays out four major challenges should be eligible for lower postal rates and that the current era poses and proposes ways to meet exemptions from sales taxes. these challenges and boost civic participation. 3. Change the tax status of papers, making them tax-exempt in some fashion. This could Challenge One: Keeping Newspapers Alive involve categorizing newspapers as “bene- fit” or “flexible purpose” corporations, or Until They Are Well treating them as for-profit businesses that have a charitable or educational purpose. A large part of the average newspaper budget com- prises costs related to printing, bundling, and deliv- ery. The development of new delivery models could greatly reduce (or perhaps eliminate) these Challenge Two: Universal Access and expenses. Potential new models use screen- Adequate Spectrum technology advancement (using new tools like the iPad) and raise subscription revenue online. -

And the Masonic Family of Idaho

The Freemasons and the Masonic Family of Idaho Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Idaho 219 N. 17th St., Boise, ID 83702 US Tel: +1-208-343-4562 Fax: +1 208-343-5056 Email: [email protected] Web: www.idahomasons.org First Printing: June 2015 online 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Attraction of Freemasonry ............................................................................................................................ 5 What they say about Freemasonry.... ........................................................................................................... 6 Grand Lodge of Idaho Territory ‐ The Beginning .......................................................................................... 7 Freemasons and Charity ............................................................................................................................... 9 Our Mission: .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Child Identification Program: .................................................................................................................... 9 Bikes for Books .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Organization Information ........................................................................................................................ -

Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 281 487 fk 012 601 AUTHOR Shane, Harold G. TITLE Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87367-434-0 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 96p. AVAILABLE FROMPhi Delta Kappa, PO Box 789, Bloomington, IN 47402 ($4,00). puB TYPE Books (010) -- Information Analyses (070) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS_PRICE_ MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Change Strategies; Computers; *Computer Uses in Education; Curriculum Development; *Educational Change; Global Approach; Mass Media Effects; Robotics; *Science and Society; *Technological Advancement; Television Research IDENTIFIERS Learning Environment; *Microelectronics ABSTRACT General background information on microtechnologies with_ implications for educators provides an introduction to this review of past and current developments in microelectronics and specific ways in which the microchip is permeating society, creating problems and opportunities both in the workplace and the home. Topics discussed in the first of two major sections of this report include educational and industrial impacts of the computer and peripheral equipment, with particular attention to the use of computers in educational institutions and in an information society; theuse of robotics, a technology now being used in more than 2,000 schools and 1,200 colleges; the growing power of the media, particularly television; and the importance of educating young learners tocope with sex, violence, and bias in the media. The second section addresses issues created by microtechnologies since the first computer made its debut in 1946; redesigning the American educational system for a high-tech society; and developing curriculum appropriate for the microelectronic age, including computer applications and changes at all levels from early childhood education to programs for mature learners. -

Reese, Stephen D., the Structure of News Sources on Television: A

Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources -

Hawaiian Day July 7

Full Moon Day July 5 According toThe Old Farmer's Almanac, July's full moon is known as the Full Buck Moon. That's because it's normally the month when a buck deer gets the beginnings of his new antlers. It's also known as the Thunder Moon (because thunderstorms are common at this time) and the Full Hay Moon. Do you know the Names of All the Full Moons? How many "moon" phrases you name? The moon phase is the shape of the directly sunlit portion of the Moon as viewed from Earth. The phases gradually change over the period of a synodic month, as the orbital positions of the Moon around Earth and of Earth around the Sun Shift. July 6 Fried Chicken Day Fried chicken has a long and interesting history—Here are a few facts: Fried Chicken Was Invented by the Scottish. Before WWII, It Was a Special Occasion Dish. Not all Chickens are Suitable for Frying. There are Three Primary Frying Methods— deep-frying ,pressure- frying (or “broasting”), cast-iron skillet . The Pressure Fryer Was the Secret to KFC’s Success. Hawaiian Day July 7 The Hawaiian Islands Kingdom was annexed by the United States on this day in 1898. Hawaii was once an independent kingdom. (1810 - 1893) The flag was designed at the request of King Kamehameha I. It has eight stripes of white, red and blue that represent the eight main islands. The flag of Great Britain is emblazoned in the upper left corner to honor Hawaii's friendship with the British. -

Air Traffic and Operational Data on Selected U.S. Airports with Parallel Runways

NASA/CR-1998-207675 Air Traffic and Operational Data on Selected U.S. Airports With Parallel Runways Thomas M. Doyle Adsystech, Inc., Hampton, Virginia Frank G. McGee Lockheed Martin Engineering & Sciences, Hampton, Virginia May 1998 The NASA STI Program Office ... in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated · CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. to the advancement of aeronautics and space Collected papers from scientific and science. The NASA Scientific and Technical technical conferences, symposia, Information (STI) Program Office plays a key seminars, or other meetings sponsored or part in helping NASA maintain this co-sponsored by NASA. important role. · SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, The NASA STI Program Office is operated by technical, or historical information from Langley Research Center, the lead center for NASA programs, projects, and missions, NASAÕs scientific and technical information. often concerned with subjects having The NASA STI Program Office provides substantial public interest. access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of aeronautical and space · TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. English- science STI in the world. The Program Office language translations of foreign scientific is also NASAÕs institutional mechanism for and technical material pertinent to disseminating the results of its research and NASAÕs mission. development activities. These results are published by NASA in the NASA STI Report Specialized services that help round out the Series, which includes the following report STI Program OfficeÕs diverse offerings include types: creating custom thesauri, building customized databases, organizing and publishing · TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of research results ... even providing videos. completed research or a major significant phase of research that present the results For more information about the NASA STI of NASA programs and include extensive Program Office, see the following: data or theoretical analysis. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

From Making What's in 1951, He Recalls Having Only 14 on His Staff: Douglas Edwards (Who Had Been Anchoring and Coproducing a 15- Minute Yours Theirs

matter of fact, the censorship has been fast Four years later, Mr. Edwards was back in view of ratings and critics' notices -but and reasonably intelligent .... at the conventions, this time to co- anchor when CBS remained second to NBC with "You get accustomed to these long -dis- some of the sessions with Walter the new team, Mr. Cronkite was brought tance conversations after a few years, but Cronkite. By then the capability of going back as "national editor" on the 1964 that first two -way with the beachhead pro- to the floor was developed and, as Mr. Ed- election night. duced a pleasant thrill. I gave [Bill] Downs wards says, "Television was less the tail From 1951, CBS did have its the go- ahead. Twenty seconds later, the being wagged by the dog; it may have been "showpiece," as Mr. Mickelson calls it- bottom fell out of the circuit and he the power." See It Now with Edward R. Murrow as became unintelligible. That's the way it Mr. Cronkite, who had been brought in host and coproducer with Fred Friendly goes. from wTOPTv Washington by Mr. (who later rose to the CBS News presiden- "Over the far shore the boys stumble Mickelson, anchored every convention cy). The program represented a move out through the dark to reach their and election night coverage from that time of the "newsreel" era. Among the show's camouflaged transmitters. They speak with the exception of 1964 when Robert innovations for television: it was the first their stories. Sometimes they get through Trout (who'd handled conventions pre- to shoot its own film and use a sound track and sometimes they don't." viously for CBS Radio) and Roger Mudd without dubbing, as well as the first to After the war, Mr. -

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT in AMERICA By. Sean P Mccracken "CBS NEWS Now Projects...NBC NEWS Is Read

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT IN AMERICA By. Sean P McCracken "CBS NEWS now projects...NBC NEWS is ready to declare ...ABC NEWS is now making a call in....CNN now estimates...declares...projects....calls...predicts...retracts..." We hear these few opening words and wait on the edges of our seats as the names and places which follow these familiar predicates make very well be those which tell us in the United States who will occupy the White House for the next four years. We hear the words, follow the talking-heads and read the ever changing scripts which scroll, flash or blink across our television screens. It is a ritual that has been repeated an-masse every four years since 1952...and for a select few, 1948. Since its earliest days, television has had a love affair with politics, albeit sometimes a strained one. From the first primitive experiments at the Republican National Convention in 1940, to the multi angled, figure laden, information over-loaded spectacles of today, the "happening" that unfolds every four years on the second Tuesday in November, known as "Election Night" still holds a special place in either our heart...or guts. Somehow, it still manages to keep us glued to our television for hours on end. This one night that rolls around every four years has "grown up" with many of us over the last 64 years. Staring off as little more than chalk boards, name plates and radio announcers plopped in front of large, monochromatic cameras that barely sent signals beyond the limits of New York City and gradually morphing into color-laden, graphic-filled, information packed, multi channel marathons that can be seen by virtually...and virtually seen by...almost any human on the planet. -

![© 2020 Media Education Foundation | Mediaed.Org 1 the MAN CARD: WHITE MALE IDENTITY POLITICS from NIXON to TRUMP [TRANSCRIPT] W](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5438/%C2%A9-2020-media-education-foundation-mediaed-org-1-the-man-card-white-male-identity-politics-from-nixon-to-trump-transcript-w-1805438.webp)

© 2020 Media Education Foundation | Mediaed.Org 1 the MAN CARD: WHITE MALE IDENTITY POLITICS from NIXON to TRUMP [TRANSCRIPT] W

THE MAN CARD: WHITE MALE IDENTITY POLITICS FROM NIXON TO TRUMP [TRANSCRIPT] WOLF BLITZER: Right now, a historic moment. We can now project the winner of the presidential race. CNN projects Donald Trump wins the presidency. JOE SCARBOROUGH: This was an earthquake unlike any earthquake I've really seen since Ronald Reagan in 1980. It just came out of nowhere. DONALD TRUMP: It's been what they call a historic event. NARRATOR: In 2016, Donald Trump pulled off one of the greatest upsets in American political history, defying both polls and pundits. JOHN ROBERTS: So help me, God. DONALD TRUMP: So help me, God. NARRATOR: Two explanations for his shocking victory dominated media coverage. One was economic and class anxiety. JAKE TAPPER: The Clinton campaign could see white working class voters going to Trump in places like Iowa and Ohio. NARRATOR: The other was racial and cultural anxiety. VAN JONES: This was a white-lash against a changing country. BAKARI SELLERS: We try to find these voters who are economic anxiety voters, but that is not what it is, Wolf. What it is is it's cultural anxiety. NARRATOR: While both explanations were legitimate, they only told part of the story. Yes, Trump won the white vote by a large margin. But a closer look inside the numbers revealed that it was white men in particular, who were most responsible for Trump's success. Trump not only won big with college educated and upper class white men. He won with a record setting margin with white working class men as well. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 8915 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS LOWELL THOMAS, LIFELONG Chose Ohio As His Birthplace

March 29, 1974 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 8915 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS LOWELL THOMAS, LIFELONG chose Ohio as his birthplace. It was the tiny the shortage of many petroleum based mate SUCCESS town of Woodington in Darke County, on rials, especially diesel fuel, gasoline and Ohio's western border. His father was Dr. asphalt cement, severe burden has been Harry George Thomas, who moved his family placed upon the highway building industry to Colorado shortly thereafter. Lowell, how and all Federal and State agencies charged HON. CLARENCE J. BROWN ever, did return to attend high school in With the responsibility of maintaining our OF OHIO Greenville, 0., for one year. State, County and City road systems, due The newscaster's early success was fore to the shortage of asphalt cement, and; IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES shadowed by his college career. He attended Whereas, the Federal allocation program Thursday, March 28, 1974 Valparaiso College in Indiana and after two has not included asphalt cement under a short years he was awarded two degrees, the mandatory allocation by the Federal Energy Mr. BROWN of Ohio. Mr. Speaker, I B.S. and M.A. Later, he attended the Univer Office and there has, therefore, been nothing know that many of my colleagues share sity of Denver and won the same two degrees proposed under any Federal Regulation which with me the respect and affection for one all over again; probably to prove the point, would require the continued manufacture of of broadcasting's most enduring person except that he won them in a single year on asphalt cement as a product thereby severely alities, Lowell Thomas.