English Reformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Was the Sermon? Mystery Is That the Spirit Blows Where It Wills and with Peculiar Results

C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL S FORUMEMINARY The Sermon 1. BIBLICAL • The sermon content was derived from Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon helped you understand the text better: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon revealed how God is at work in the text: 1 2 3 4 5 How Was the• The sermonSermon? displayed the grace of God in Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 1=Excellent 2=Very Good 3=Good 4=Average 5=Poor W INTER 2008 C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL SEMINARY from the president FORUM Cornelius Plantinga, Jr. Providing Theological Leadership for the Church Volume 15, Number 1 Winter 2008 Dear Brothers and Sisters, REFLECTIONS ON Every Sunday they do it again: thousands of ministers stand before listeners PREACHING AND EVALUATION and preach a sermon to them. If the sermon works—if it “takes”—a primary cause will be the secret ministry of the Holy Spirit, moving mysteriously through 3 a congregation and inspiring Scripture all over again as it’s preached. Part of the How Was the Sermon? mystery is that the Spirit blows where it wills and with peculiar results. As every by Scott Hoezee preacher knows, a nicely crafted sermon sometimes falls flat. People listen to it 6 with mild interest, and then they go home. On other Sundays a preacher will Good Preaching Takes Good Elders! walk to the pulpit with a sermon that has been only roughly framed up in his by Howard Vanderwell (or her) mind. The preacher has been busy all week with weddings, funerals, and youth retreats, and on Sunday morning he isn’t ready to preach. -

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes Adam Giancola of the Waldensian Experience The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes of the Waldensian Experience Adam Giancola In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the experience of many countries across Europe was the complete overturning of traditional institutions, whereby religious dissidence became a widespread phenomenon. Yet the focus on Reformation history has rarely been given to countries like Italy, where a strong Catholic presence continued to persist throughout the sixteenth century. In this regard, it is necessary to draw attention to the ‘Italian Reformation’ and to determine whether or not the ideas of the Reformation in Western Europe had any effect on the religious and political landscape of the Italian peninsula. In extension, there is also the task to understand why the Reformation did not ‘succeed’ in Italy in contrast to the great achievements it made throughout most other parts of Western Europe. In order for these questions to be addressed, it is necessary to narrow the discussion to a particular ‘Protestant’ movement in Italy, that being the Waldensians. In an attempt to provide a general thesis for the ‘failure’ of the Protestant movement throughout Italy, a particular look will be taken at the Waldensian case, first by examining its historical origins as a minority movement pre-dating the European Reformation, then by clarifying the Waldensian experience under the sixteenth century Italian Inquisition, and finally, by highlighting the influence of the Counter-Reformation as pivotal for the future of Waldensian survival. Perhaps one of the reasons why the Waldensian experience differed so greatly from mainstream European reactions has to do with its historical development, since in many cases it pre-dated the rapid changes of the sixteenth century. -

A Manual of Church Membership

: ,CHURCH MEMBERSHIP THE LINDSBY PRESS This little book has been prepared by the Religious ; ;!.L ,,S&:, ' Education Department of the General Assembly of ' ,; Unitarian and Free Christian Churches to fill a gap in our denominational bookshelf. Many books and pamphlets have been issued to explain our history . and our theological position, but nothing has been published to state in simple language and as concisely as possible what is implied by membership . of a congregation in fellowship with the General' " Assembly. Our method has been to try to suggest the questions about church membership which need answers, and to supply the kernel to the answer, while leaving the reader to find out more inform- ation for himself. We hope the booklet wi! be found useful not only by young people growing up in our tradition (whose needs, perhaps, we have had chiefly in mind), but also by older men and if.+ ?( .%=. women, especially those who are new to our denominational fellowship, and by the Senior Classes of Sunday Schools, and study groups of branches of the Young People's League, and by Ministers' Classes preparing young people for ..;:L.-q-,:sy . .* Made and Printed in Great B~itailaby C. Ti~lifigG Co. U$&.- church membership. ..c:.' Liver$ool, Lofidon, and Prescot. .? 5 CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE I. OUR HERITAGE . 4 9 11. WHAT IS I%UR CHURCH ? . 12' 111. WHAT IS YOUR CHURCH FOR ? . I7 IV. WHAT IS THE DISTINCTIVE TEACHING ?. 24 V. SPECIAL OFFICES AND SACRAMENTS . 3 I VI. HOW IS YOUR CHURCH MANAGED ? martyrs who suffered for their faith. The meaning)"- of our history is revealed in the struggle of manylLC generations of mefi and women to win freedom of kfi: thought and speech in religious matters, while ri ..h. -

Fr Cantalamessa Gives First Advent Reflection to Pope and Roman Curia

Fr Cantalamessa gives first Advent reflection to Pope and Roman Curia The Preacher of the Papal Household, Fr Raniero Cantalamessa, gives his first Advent reflection at the Redemptoris Mater Chapel in the Apostolic Palace. Below is the full text of his sermon. P. Raniero Cantalamessa ofmcap BLESSED IS SHE WHO BELIEVED!” Mary in the Annunciation First Advent Sermon 2019 Every year the liturgy leads us to Christmas with three guides: Isaiah, John the Baptist and Mary, the prophet, the precursor, the mother. The first announced the Messiah from afar, the second showed him present in the world, the third bore him in her womb. This Advent I have thought to entrust ourselves entirely to the Mother of Jesus. No one, better than she can prepare us to celebrate the birth of our Redeemer. She didn’t celebrate Advent, she lived it in her flesh. Like every mother bearing a child she knows what it means be waiting for somebody and can help us in approaching Christmas with an expectant faith. We shall contemplate the Mother of God in the three moments in which Scripture presents her at the center of the events: the Annunciation, the Visitation and Christmas. 1. “Behold, / am the handmaid of the Lord” We start with the Annunciation. When Mary went to visit Elizabeth she welcomed Mary with great joy and praised her for her faith saying, “Blessed is she who believed there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken her from the Lord” (Lk 1:45). The wonderful thing that took place in Nazareth after the angel’s greeting was that Mary “believed,” and thus she became the “mother of the Lord.” There is no doubt that the word “believed” refers to Mary’s answer to the angel: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word (Lk 1:38). -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Robert M. Andrews the CREATION of a PROTESTANT LITURGY

COMPASS THE CREATION OF A PROTESTANT LITURGY The development of the Eucharistic rites of the First and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI ROBERT M. ANDREWS VER THE YEARS some Anglicans Anglicanism. Representing a study of have expressed problems with the Archbishop Thomas Cranmer's (1489-1556) Oassertion that individuals who were liturgical revisions: the Eucharistic Rites of committed to the main tenets of classical 1549 and 1552 (as contained within the First Protestant theology founded and shaped the and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI), this early development of Anglican theology.1 In essay shows that classical Protestant beliefs 1852, for example, the Anglo-Catholic were influential in shaping the English luminary, John Mason Neale (1818-1866), Reformation and the beginnings of Anglican could declare with confidence that 'the Church theology. of England never was, is not now, and I trust Of course, Anglicanism changed and in God never will be, Protestant'.2 Similarly, developed immensely during the centuries in 1923 Kenneth D. Mackenzie could, in his following its sixteenth-century origins, and 1923 manual of Anglo-Catholic thought, The it is problematic to characterize it as anything Way of the Church, write that '[t]he all- other than theologically pluralistic;7 nonethe- important point which distinguishes the Ref- less, as a theological tradition its genesis lies ormation in this country from that adopted in in a fundamentally Protestant milieu—a sharp other lands was that in England a serious at- reaction against the world of late medieval tempt was made to purge Catholicism English Catholic piety and belief that it without destroying it'.3 emerged from. -

Preacher Title III, Canon 4, Sec.5

Preacher Title III, Canon 4, Sec.5 A Preacher is a lay person authorized to preach. Persons so authorized shall only preach in congregations under the direction of the Member of Clergy or other leader exercising oversight of the congregation or other community of faith. Discernment Candidates considering the ministry of Preacher should confer with sponsoring clergy, spiritual directors, or other vocational guides to discuss honestly how to test a call, as well as the practicalities of the preaching ministry. During the period of discernment, candidates should familiarize themselves with various theologies and theories of preaching, so that their models of preaching are not limited by the examples they have observed in their immediate context. Some resources to aid in discernment are listed at the end of this document. It is not necessary to purchase and read all the resources on this extensive list in order to become licensed. Start with the basics and use the resource list for your continuing education and skill building in this ministry. Discernment Questions for those discerning a call to this ministry: • Have I imagined myself preaching? How did that feel? • Have I found I wanted to investigate the meaning of the scriptures more deeply than I have in the past? • Am I curious about Christian theology or the history of the Church? • Have I asked God whether God might be calling me to this ministry? • Have friends, clergy, or fellow-parishioners suggested I think about a preaching ministry? • Do I feel relatively comfortable speaking -

Abstract Preacher-As-Witness

ABSTRACT PREACHER-AS-WITNESS: THE HOMILETICAL APPROACH OF E. STANLEY JONES by Luke Molberg Pederson Witness is a key metaphor that addresses postmodern yearning for authenticity and integrity in preaching in the current cultural milieu of the United States and Canada. The speaking and writing of twentieth-century world missionary and evangelist E. Stanley Jones provided a bountiful source of autobiographical material through which to explore Jones’ self- understanding as preacher-as-witness. The purpose of the study was to describe Jones’ homiletical self-understanding as witness to Jesus Christ, analyze the content of his speaking and writing as it pertains to preaching, and outline his sermonic approach. Jones’ underlying homiletical worldview was probed in its natural context through a grounded theory process of simultaneous data collection, analysis, and synthesis. All of Jones’ twenty-seven published books were scrutinized as well as ten selected sermons in print and in audio and videotape formats spanning sixty years of Jones’ preaching ministry. Samples of my own preaching were appended as examples of the integration of Jones’ approach with postmodern praxis. The focus of the study was not on others’ assessment of Jones, or critical evaluation of his preaching, but on his self- understanding as witness to Jesus Christ as a means to inform the present opportunity for preaching in a postmodern context. The study clarified boundaries between the metaphors of testimony, confession, and witness, offered an extension of Thomas G. Long’s work on the witness of preaching as an underappreciated metaphor for preaching, and presented witness as a theoretical bridge between speaker-driven and audience-driven polarities in preaching. -

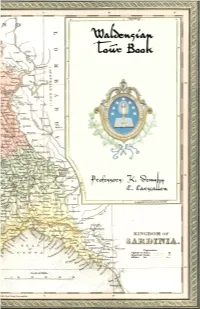

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

“The Poor Men of Lyon”

“THE POOR MEN OF LYON” A display prepared for the URC History Society Conference at Westminster College in June 2019 looked at some of the books about the Waldensians in the URCHS collections. In the 1170s, ‘Peter’ Waldo or Valdès (c.1140-c.1205) gave away all his possessions and formed the Poor Men of Lyon. Know by his name in the Provençal, Italian, or Latin forms, his followers were later known as the Vaudois, the Valdesi, and the Waldenses or Waldensians – but they referred to themselves as the Poor Men of Lyon, or the Brothers. A movement which was characterised by voluntary poverty, lay preaching, and literal interpretation of the Bible (which they translated into the vernacular), the Poor Men soon came into conflict with the Catholic Church, and were declared to be heretical in 1215. As they were persecuted in France, they moved deeper into the high Alpine valleys between France and Italy, into Piedmont. One of the earliest statements of faith for the movement is a Provençal poem dating from c.1200, entitled “La Nobla Leyczon” – in English, The Noble Lesson. During the Reformation, the Poor were hailed as early and faithful proponents of Protestant ideas – the poet John Milton (1608- 1674), writing a sonnet about the Piedmont Easter massacre in 1655, refers to them as ‘them who kept thy truth so pure of old”. Images reproduced with the permission of the United Reformed Church History Society map from ‘Narrative of an Excursion into the Mountains of Piemont’, by William Gilly (1825) (left) This map of 1825 shows the area of Savoy from which the Vaudois moved into Piedmont, in Northern Italy, and the three key valleys of Lucerna, San Martino, and Perosa. -

Seeking Primitive Christianity in the Waldensian Valleys

NR 904 02:28:2006 11:53 AM Page 5 Seeking Primitive Christianity in the Waldensian Valleys Protestants, Mormons, Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses in Italy Michael W. Homer ABSTRACT: During the nineteenth century, Protestant clergymen (Anglican, Presbyterian, and Baptist) as well as missionaries for new reli- gious movements (Mormons, Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses) believed that Waldensian claims to antiquity were important in their plans to spread the Reformation to Italy. The Waldensians, who could trace their historical roots to Valdes in 1174, developed an ancient origins thesis after their union with the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. This thesis held that their community of believers had preserved the doctrines of the primitive church. The competing churches of the Reformation believed that the Waldensians were “destined to fulfill a most important mission in the Evangelization of Italy” and that they could demonstrate, through Waldensian history and practices, that their own claims and doctrines were the same as those taught by the primitive church. The new religious movements believed that Waldensians were the best prepared in Italy to accept their new revelations of the restored gospel. In fact, the initial Mormon, Seventh-day Adventist, and Jehovah’s Witness converts in Italy were Waldensians. By the end of the century, however, Catholic, Protestant, and Waldensian scholars had debunked the thesis that Waldensians were proto-Protestants prior to Luther and Calvin. n June 1850 Mormon Apostle Lorenzo Snow (1814–1901) opened the Italian Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia. He chose this location Ibecause he believed, based on a tract he read in England, that the Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 9, Issue 4, pages 5–33, ISSN 1092-6690 (print), 1541–8480 (electronic). -

How English Baptists Changed the Early Modern Toleration Debate

RADICALLY [IN]TOLERANT: HOW ENGLISH BAPTISTS CHANGED THE EARLY MODERN TOLERATION DEBATE Caleb Morell Dr. Amy Leonard Dr. Jo Ann Moran Cruz This research was undertaken under the auspices of Georgetown University and was submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in History at Georgetown University. MAY 2016 I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. ABSTRACT The argument of this thesis is that the contrasting visions of church, state, and religious toleration among the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists in seventeenth-century England, can best be explained only in terms of their differences over Covenant Theology. That is, their disagreements on the ecclesiological and political levels were rooted in more fundamental disagreements over the nature of and relationship between the biblical covenants. The Baptists developed a Covenant Theology that diverged from the dominant Reformed model of the time in order to justify their practice of believer’s baptism. This precluded the possibility of a national church by making baptism, upon profession of faith, the chief pre- requisite for inclusion in the covenant community of the church. Church membership would be conferred not upon birth but re-birth, thereby severing the links between infant baptism, church membership, and the nation. Furthermore, Baptist Covenant Theology undermined the dominating arguments for state-sponsored religious persecution, which relied upon Old Testament precedents and the laws given to kings of Israel. These practices, the Baptists argued, solely applied to Israel in the Old Testament in a unique way that was not applicable to any other nation. Rather in the New Testament age, Christ has willed for his kingdom to go forth not by the power of the sword but through the preaching of the Word.