Resolving Labour Shortage? the Digital Transformation of Working Practices in the Japanese Service Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About HCJ Visitors Information

About HCJ What is HCJ? Visitors information With its history of over 40 years, HCJ is highly recognized by all business Show Information persons in Japanese hospitality industry. 850 exhibitors and 60,000 visitors makes the event most energetic. This is a "must-visit" show for the professionals, especially for those involved Business process is speedy and effective. (expected) Date February 20(Tue.) -23(Fri.), 2018 Scale in newly opening hotels, restaurants and commercial facilities. 10:00 - 17:00 (16:30 on the last day) 850 companies / 2,100 booths / 18,900 sq.m. (HCJ2017 results) ● HOTERES JAPAN: International hotels & restaurant trade show for hotels, "ryokan"s, travel, and facilities. HCJ Brings Powerful Visitors! Number of Visitors (expected) Venue Tokyo Big Sight ● CATEREX JAPAN: Food and catering trade show for catering and food services. (Tokyo International Exhibition Center, Japan) 60,000 professionals ● JAPAN FOOD SERVICE EQUIPMENT SHOW: Equipment for commercial kitchens and food services trade show. By Sector Number of Visitors 56,367 What are the purposes of your visit? Three events are held simultaneously, providing the largest business matching opportunity for hospitality & food service industry in Japan! (multiple answers) Organized by Restaurants, Food Services 11,048 19.6% To gather information on new products/services 49.4% Japan Management Association Japan Hotel Association Manufacturing 10,333 17.8% To gather information for product purchasing 26.3% Japan Ryokan & Hotel Association Japan Restaurant Association Target Exhibits / Zoning To purchase ( or examine ) products 25.6% Japan Tourism Facilities Association Hotels,Inns 9,639 17.1% To ascertain current trends in related markets 22.8% Organized by Renewal Continuation & Expansion Please choose from the four zones. -

4.1 Potential Facilities List FY 17-18

FY 2017-2018 Annual Report Permittee Name: City of San José Appendix 4.1 FAC # SIC Code Facility Name St Num Dir St Name St Type St Sub Type St Sub Num 820 7513 Ryder Truck Rental A 2481 O'Toole Ave 825 3471 Du All Anodizing Company A 730 Chestnut St 831 2835 BD Biosciences A 2350 Qume Dr 840 4111 Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Chaboya Division A 2240 S 7th St 841 5093 Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority - Cerone Division A 3990 Zanker Rd 849 5531 B & A Friction Materials, Inc. A 1164 Old Bayshore Hwy 853 3674 Universal Semiconductor A 1925 Zanker Rd 871 5511 Mercedes- Benz of Stevens Creek A 4500 Stevens Creek Blvd 877 7542 A.J. Auto Detailing, Inc. A 702 Coleman Ave 912 2038 Eggo Company A 475 Eggo Way 914 3672 Sanmina Corp Plant I A 2101 O'Toole Ave 924 2084 J. Lohr Winery A 1000 Lenzen Ave 926 3471 Applied Anodize, Inc. A 622 Charcot Ave Suite 933 3471 University Plating A 650 University Ave 945 3679 M-Pulse Microwave, Inc. A 576 Charcot Ave 959 3672 Sanmina Corp Plant II A 2068 Bering Dr 972 7549 San Jose Auto Steam Cleaning A 32 Stockton Ave 977 2819 Hill Bros. Chemical Co. A 410 Charcot Ave 991 3471 Quality Plating, Inc. A 1680 Almaden Expy Suite 1029 4231 Specialty Truck Parts Inc. A 1605 Industrial Ave 1044 2082 Gordon Biersch Brewing Company, Inc. A 357 E Taylor St 1065 2013 Mohawk Packing, Div. of John Morrell A 1660 Old Bayshore Hwy 1067 5093 GreenWaste Recovery, Inc. -

Ohsho Food Service Junichi Shimizu Chief Analyst, Head of Research TSE 1St Section 9936 Industry: Food Service, Retail Gold Medalist in Chinese Cuisine

MITA SECURITIES Equity Research June 22, 2021 MITA SECURITIES Co., Ltd. Ohsho Food Service Junichi Shimizu Chief Analyst, Head of Research TSE 1st Section 9936 Industry: Food service, retail Gold medalist in Chinese cuisine. Enjoy Initiation of coverage dumplings in store or at home; initiating coverage with a Buy rating Rating Initiating coverage with a TP of 7,250 yen and a Buy rating We initiate coverage of Ohsho Food Service Corporation (9936, Ohsho Food Service, the Buy company) with a target price of 7,250 yen and a Buy rating. Target price (JPY) 7,250 The company operates “Gyoza no Ohsho,” the largest Chinese restaurant chain, both Stock price (JPY) (Jun 21) 5,610 directly and through franchisees nationwide. The company’s earnings have been robust Market cap (JPYbn) 130.6 since pre-COVID-19 pandemic. Although sales of in-store dining declined as it was forced Key changes to shorten business hours in the wake of the COVID-19, sales of take-out and delivery have Rating New been strong. The company posted an OP of 6.1bn yen (OPM 7.5%) in FY3/21 while many of Target price New its competitors posted losses. With the withdrawal of underperforming restaurants, the Earnings forecast New potential locations for new openings have been increasing. The company appears to be the Stock price (JPY) only major Chinese restaurant chain that can continue to make positive investments. In our 10,000 view, the company’s competitive advantage will continue to strengthen. 9,000 8,000 7,000 The catalysts we envision for an upturn in the stock price include strong monthly same- 6,000 5,000 store sales, recovery in quarterly profits, easing of requests by local governments to 4,000 3,000 shorten business hours, and progress in vaccination against the COVID-19. -

HIDAY HIDAKA Corporation

HIDAY HIDAKA Corporation Restaurant chain serving ramen and Chinese dishes to the mass-market: focusing on new business formats despite the impact of COVID-19 TICKER: 7611 | TSE1 | HP: http://hidakaya.hiday.co.jp/english/ | LAST UPDATE: 2021.08.23 Business Strengths and weaknesses Runs Hidakaya restaurant chain near train stations in Greater Tokyo; particular focus Strengths on opening new branches in Kanagawa Cost advantages from area-dominant Business model: Core business is chain of Hidakaya restaurants (94.2% of strategy and central kitchen: GPM above FY02/21 sales) that serve ramen, gyoza (dumplings), and other popular Chinese 70% for over 20 years through FY02/21, dishes. It also offers side dishes that go with alcohol for customers who want a despite relatively low-price menu. One of only quick drink. Customers range from students to businesspeople, late-shift workers, a handful of leading listed restaurant and seniors, all attracted by affordable prices (JPY390 for ramen and JPY230 for operators with a GPM above 70%. gyoza including tax) and late hours (nearly half of stores are open till 2 a.m.; more Directly operated restaurants maintain than 10% are open 24 hours*). Average customer spend is about JPY750 (before quality, boost brand power, and enable tax; FY02/21). Per the company, no other chain operates the same restaurant flexible operations format (serving both ramen and Chinese dishes). From FY02/10 to FY02/19, Low prices and classic dishes keep HIDAY HIDAKA maintained an OPM of over 10%, but in FY02/21 sales fell and the customers coming back: Maintained company posted an operating loss, due in large part to shortened opening hours comparable store sales of at least 100% YoY amid the COVID-19 outbreak. -

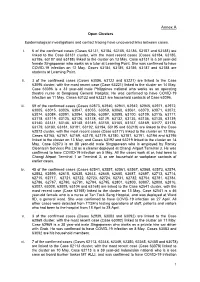

Annex a Open Clusters

Annex A Open Clusters Epidemiological investigations and contact tracing have uncovered links between cases. i. 6 of the confirmed cases (Cases 63131, 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188) are linked to the Case 63131 cluster, with the most recent cases (Cases 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188) linked to the cluster on 13 May. Case 63131 is a 50 year-old female Singaporean who works as a tutor at Learning Point. She was confirmed to have COVID-19 infection on 12 May. Cases 63184, 63185, 63186, 63187 and 63188 are students at Learning Point. ii. 3 of the confirmed cases (Cases 63096, 63122 and 63221) are linked to the Case 63096 cluster, with the most recent case (Case 63221) linked to the cluster on 14 May. Case 63096 is a 33 year-old male Philippines national who works as an operating theatre nurse at Sengkang General Hospital. He was confirmed to have COVID-19 infection on 11 May. Cases 63122 and 63221 are household contacts of Case 63096. iii. 59 of the confirmed cases (Cases 62873, 62940, 62941, 62942, 62945, 62971, 62972, 63005, 63015, 63026, 63047, 63055, 63059, 63060, 63061, 63070, 63071, 63072, 63074, 63084, 63091, 63094, 63095, 63097, 63098, 63100, 63109, 63115, 63117, 63118, 63119, 63125, 63126, 63128, 63129, 63132, 63135, 63136, 63138, 63139, 63140, 63141, 63146, 63148, 63149, 63150, 63165, 63167, 63169, 63177, 63178, 63179, 63180, 63181, 63191, 63192, 63194, 63195 and 63219) are linked to the Case 62873 cluster, with the most recent cases (Case 63177) linked to the cluster on 12 May, Cases 63165, 63167, 63169, 63178, 63179, 63180, 63181, 63191, 63194 and 63195 linked to the cluster on 13 May, and Cases 63192 and 63219 linked to the cluster on 14 May. -

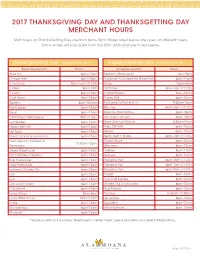

2017 Thanksgiving Day and Thanksgetting Day Merchant Hours

2017 THANKSGIVING DAY AND THANKSGETTING DAY MERCHANT HOURS Mall hours on ThanksGetting Day are from 6am−9pm. Stores listed below are open at different hours. Some stores will stay open from the 23th−24th and are noted below. THANKSGIVING DAY NOVEMBER 23, 2017 THANKSGIVING DAY NOVEMBER 23, 2017 Store/Restaurant Hours Store/Restaurant Hours Aldo etc. 6pm–12am Morton’s Steakhouse 1pm–9pm Chapel Hats 6pm–10pm Nagasaki Champon by Ringer Hut 6pm–11pm Cho Dang 8am–1am (11/24) Nijiya 10am–6pm Claire’s 5pm–1am Old Navy 3pm–1am (11/24) Coach 6pm–12am Panda Express 6pm–12am Cole Haan 9pm–12am Panini Grill 6pm–12am Express 6pm–12amw Patisserie La Palme D’Or 9:30am–2pm Foot Locker 6pm–12am Rip Curl 6pm–2am (11/24) Fossil 6pm–12am Rokkaku Hamakatsu 6pm–10pm GEN Korean BBQ House 10am–11pm Ross Dress For Less 6pm–12am Gymboree 6pm–12am Saint Germain Bakery 8:30am–2pm Happy Wahine 6pm–12am Saks OFF 5TH 6pm–12am Hot Topic 6pm–12am Sbarro 6pm–12am Island Crepes & Lemonade 6pm–12am Sera’s Surf ’n Shore 8pm–1am (11/24) Jade Dynasty Seafood & Shoe Palace 6pm–12am 10:30am–10pm Restaurant Skechers 6pm–12am Jeans Warehouse 6pm–12am Sobaya 6pm–11pm John Masters Organics 6pm–12am Subway 6pm–12am Kids FootLocker 6pm–12am Sunglass Hut 6pm–2am (11/24) Lady FootLocker 6pm–12am Sunglass Hut 6pm–2am (11/24) Lahaina Chicken Co. 6pm–12am Sunglass Hut 6pm–2am (11/24) Lids 6pm–12am Target 6pm–12am Lids 6pm–12am Toys R US Express 6pm–12am Lids Locker Room 6pm–12am Tricked Out Accessories 6pm–12am L’Occitane 6pm–12am True Friends 6pm–12am Longs Drugs 5am–5pm Truffaux 5:30pm–12:30am Lucky Strike Social 10am–12am VR Junkies 6pm–12am malie 6pm–12am Sugarfina 6pm–12am Michael Kors 6pm–12am Wind Spinners 6pm–12am Microsoft 6pm–12am *Sunglass Hut has 3 locations: Street Level 1, Center Court, Level 3, Ewa Wing and Level 3, Mauka Wing. -

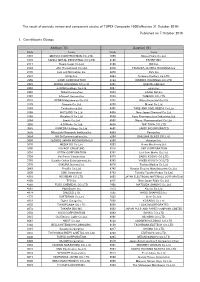

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

Exhibition for Hospitality, Food Service and Catering Industries!

Exhibition for Hospitality, Food Service and Catering Industries! 44th Japan Management Association Japan Hotel Association Japan Ryokan & Hotel Association Japan Restaurant Association Japan Tourism Facilities Association 37th Japan Contract Food Service Association Japan Lunch Food Service Association Japan Food Service for Patients Association Japan Management Association Japan Food Service Equipment Association Japan Japan ManagementManagement AssociAssociationation Date February 16(Tue.) ~ 19(Fri.), 2016 10:00~17:00(Last day 10:00~16:30) Venue Tokyo Big Sight (Tokyo International Exhibition Center, Ariake) 811 companies / 1,947 booths / 17,523sq.m. scale Japan’s largest trade show for hospitality, food service and catering! HCJ represents the three trade shows: ● HOTERES JAPAN: International hotels & restaurant trade show for hotels, "ryokan"s, travel, and facilities. ● CATEREX JAPAN: Food and catering trade show for catering and food services. ● JAPAN FOOD SERVICE EQUIPMENT SHOW: Equipment for commercial kitchens and food services trade show. Three events are held simultaneously, H for HOTERES JAPAN, providing the largest business matching for CATEREX JAPAN, and opportunity for hospitality & food C service industry in Japan! J for JAPAN FOOD SERVICE EQUIPMENT SHOW. (The 44th International Hotel & Restaurant Show) * & ' ( ! ) $)% "# $"% (The 37th Exhibition for the Catering Industries) + * ! -(* ! * ! &, * & ' ( & ('-/ & &" '+ '* * ( ! ( -

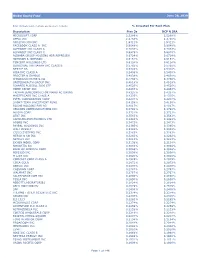

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767% -

Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund Annual Report October 31, 2020

Annual Report | October 31, 2020 Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com. Your election to receive paper copies will apply to all the funds you hold through an intermediary or directly with Vanguard. -

Meet 65,000 Buyers in Hotel, Restaurant and Food Service Industry

Japan’s Largest Exhibition for Hospitality Standard Booth (Space ONLY) Special Trade show for Food-service, Accommodation & Leisure industries 1 booth=9㎡ (W2,970mm× D2,970mm× H2,700mm) Early bird 2700㎜ Early bird discount discount 47 [Until Jul. 31] 378,000 JPY (tax incl.) 75,600 Final application JPY No carpet [Until Sep. 28] 453,600 JPY (tax incl.) 2970㎜ 2970㎜ Option: Package Plan Trade show for Food-service & Home delivery 40 1 booth with Package W2,970×D2,970×H2,700 unit/ mm Company name Outlet 507,600 JPY (Early bird) Price Fascia board 583,200 JPY (Final Application) (incl. Construction fee & 8% consumption tax) 1. Fascia board + Company name 5-3 Rental equipment (Choose 3 items) Trade show for Kitchen equipment 2. Outlet (100V, Single phase) J. Rectangle table (Choose 1 item) 3. Carpet (Choose your own color) K. Wall shelf (x 1 unit) 4. Meeting set L. White cloth (2200x1000mm x 3 units) 5. Rental equipments (Choose your own)※ M. Brochure stand (A4 size, 6 rows) 5-1 Electrical equipment (Choose 3 items) N. Panel stand (Choose 1 item) 2700 A. Fluorescent light (40W) O. Fire extinguisher B. Spotlight (100W) P. Table-top brochure stand & Business card box C. Arm spotlight (100W) Q. Hanger stand (x 1 unit) & Hangers (x 10 units) 5-2 Rental equipment (Choose 1 item) ※Check the official website or contact the Secretariat Carpet D. Reception counter 6. Electricity (Choose your own color) E. Square table (Choose 1 item) Electric wiring work (Up to 1kW/ 100V) Date Venue F. Counter table (φ600xH1000mm) Electricity usage (1kW/ For set up & show period ) 2970 Tue Fri G. -

HIDAY HIDAKA Corporation

HIDAY HIDAKA Corporation Restaurant chain serving ramen and Chinese dishes to the mass-market: focusing on new business formats despite the impact of COVID-19 TICKER: 7611 | TSE1 | HP: http://hidakaya.hiday.co.jp/english/ | LAST UPDATE: 2020.05.12 Business Strengths and weaknesses Runs Hidakaya restaurant chain near train stations in Greater Tokyo; particular focus Strengths on opening new branches in Kanagawa Cost advantages from area-dominant Business model: Core business is chain of Hidakaya restaurants (94.3% of strategy and central kitchen: OPM above FY02/20 sales) that serve ramen, gyoza (dumplings), and other popular Chinese 10% from FY02/12 through FY02/19, despite dishes. It also offers side dishes that go with alcohol for customers who want a relatively low-price menu (FY02/20 OPM of quick drink. Customers range from students to businesspeople, late-shift workers, 9.7%) and seniors, all attracted by affordable prices (JPY390 for ramen and JPY230 for Directly operated restaurants maintain gyoza including tax) and late hours (nearly half of stores are open till 2 a.m.; more quality, boost brand power, and enable than 10% are open 24 hours*). Average customer spend is about JPY730 (before flexible operations tax; FY02/20). Per the company, no other chain operates the same restaurant Low prices and classic dishes keep format (serving both ramen and Chinese dishes). From FY02/10 to FY02/19, customers coming back: Maintained HIDAY HIDAKA has maintained an OPM of over 10%, but in FY02/20 the OPM was comparable store sales of at least 100% YoY 9.7%. for eight years through FY02/19 (down 1.8% *Since April 24, 2020, stores in Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Ibaraki have been closing at 8 p.m., YoY in FY02/20) while those in Saitama and Chiba have been closing at 11 p.m., in compliance with the Weaknesses central government’s COVID-19-related state of emergency declaration, and requests for cooperation from affected cities and prefectures.