Intelligence Memorandum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conclusion: How the GDR Came to Be

Conclusion: How the GDR Came to Be Reckoned from war's end, it was ten years before Moscow gave real existing socialism in the GDR a guarantee of its continued existence. This underscores once again how little the results of Soviet policy on Germany corresponded to the original objectives and how seriously these objectives had been pursued. In the first decade after the war, many hundreds of independent witnesses confirm that Stalin strove for a democratic postwar Germany - a Germany democratic according to Western standards, which must be explicitly emphasized over against the perversion of the concept of democracy and the instrumentalization of anti-fascism in the GDR. 1 This Germany, which would have to of fer guarantees against renewed aggression and grant access to the re sources of the industrial regions in the western areas of the defeated Reich, was to be established in cooperation with the Western powers. To this purpose, the occupation forces were to remain in the Four Zone area for a limited time. At no point could Stalin imagine that the occupation forces would remain in Germany permanently. Dividing a nation fitted just as little with his views. Socialism, the socialist revolution in Germany, was for him a task of the future, one for the period after the realization of the Potsdam democratization programme. Even when in the spring of 1952, after many vain attempts to implement the Potsdam programme, he adjusted himself to a long coexistence of the two German states, he did not link this with any transition to a separate socialism: the GDR had simply wound up having to bide its time until the Cold War had been overcome, after which it would be possible to realize the agree ments reached at Potsdam. -

THE NEW STAGE of the SINO-SOVIET DISPUTE (October 1961 - January 1962) (Reference Title: ESAU XVII-62)

,- APPROVED.$OR RELEASE DATE: MAY 2007 I 26 February 1962 OCI No. 0361/62 Copy No. .,.-4 23 CURRENT INTELLIGENCE STAFF STUDY THE NEW STAGE OF THE SINO-SOVIET DISPUTE (October 1961 - January 1962) (Reference Title: ESAU XVII-62) I Office 03,Current Intelligence CENTM'd INTELLIGENCE AGENCY NTAINS INFORM T€E NEW STAGE OE THE SINO-SOVIET DISPUTE (October IXEl - January 1962) This is a working paper, our first systematic survey since spring 1961 of the Sino-Soviet dispute. This paper discusses the stage initiated by Khrushchev's new offensive at the 22nd CPSU Congress in October 1961, examines the forms of pressure on the Chinese still available to Khrushchev, and speculates on the possibility of' a Sino-Soviet break in the next year or so. We have had profitable discussions, on many of the mat- in this paper. wi umber of other analysts. I I: I I . THE NEW STAGE OF THE SINO-SOVIET DISPUTE Summary and Conclusions .................................... i I . THl3 BACKGROUND ....................................... 2 A . The "Personality Cult............................. 2 B . World Communist Strategy ......................... 3 C . Chinese Programs and Soviet Aid .................. 5 D . Authority & Discipline in the Movement ...........6 E . Soviet-Albanian Relations ........................ 7 I1 . DEVELOPMENTS AT TI# 22ND CPSU CONGRESS (October 1961) ..................................... 11 A; The "Personality Cult" Again .................... 11 B . Soviet Strategy Reaffirmed ......................13 C . Chinese Prograins Criticized. Soviet Aid Brandished ..................................... 16 D . Soviet Authority in Movement Reasserted .........18 111 . TO THE BREAK iVITH ALBANIA (November 1961) ........... 26 A . Soviet-Albanian Polemics ........................26 B . Chinese Support of Albania.. .................... 30 C . Soviet Warnings to China ........................ 34 I IV . PRESSURE AND RESISTANCE (December 1961) ............ -

I I I I I I I ISBN: 0-85964-482-0 I I I J :1 I I I TABLE of CONTENTS I PREFACE Iii

A R C H. I V E S 0 F T H E 'I SOVIET COMMUNIST PARTY AND SOVIET STATE I I I I I Catalogue of Finding Aids and Docun1ents I fro1n three kev•. : archives i on n1icrofihn I I Fourth edition: June 2004 I I Published jointly by Slate Archival Service Hoover Institution on vVar. I Revolution and Peace of Russi a CRo' sarkhi \ .·) I I Distributed b\· l CfJ.., CHA D\VYCK-llFALEY 1:~ I f 1· I I I I Fourth Edition: June 2004 I I I I I I I ISBN: 0-85964-482-0 I I I J :1 I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I PREFACE iii I INTRODUCTION v I HOW TO USE THE CATALOGUE xiii HOW TO ORDER MICROFILM XIV I LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvii CENTRE FOR THE PRESERVATION OF CONTEMPORARY DOCUMENTATION (TsKhSD) I [Renamed Russian State Archive of Contemporary History - RGANI] OPISI I FINDING AIDS SERIES 1 I DELA/DOCUMENTS SERIES 2 ~ I RUSSIAN CENTRE FOR THE PRESERVATION AND STUDY OF DOCUMENTS OF MOST RECENT HISTORY (RTsKhIDNI) I [Renamed Russian State Archive of Social and Political History - RGASPI] OPISI I FINDING AIDS SERIES 3 I DELA/ DOCUMENTS SERIES 10 STATE ARCHIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (GARF) I r-series [Collection held at Pirogovskaia Street] OPISI I FINDING AIDS SERIES 15 I DELA I DOCUMENTS SERIES 57 I STATE ARCHIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION (GARF) a-series [Collection held at Berezhkovskaia Naberezhnaia] I OPISI I FINDING AIDS SERIES 69 I DELA I DOCUMENTS SERIES 89 I, I I I 111 I PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION I The State Archival Service of the Russian Federation (Rosarkhiv), the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, and Chadwyck-Healey concluded an agreement in April 1992 to I microfilm the records and opisi (finding aids) of the Communist Party of the fonner Soviet Union, as well as other selected holdings of the State Archives. -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN Issue 10 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. March 1998 Leadership Transition in a Fractured Bloc Featuring: CPSU Plenums; Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and the Crisis in East Germany; Stalin and the Soviet- Yugoslav Split; Deng Xiaoping and Sino-Soviet Relations; The End of the Cold War: A Preview COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 The Cold War International History Project EDITOR: DAVID WOLFF CO-EDITOR: CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN ADVISING EDITOR: JAMES G. HERSHBERG ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTA SHEEHAN MATTHEW RESEARCH ASSISTANT: ANDREW GRAUER Special thanks to: Benjamin Aldrich-Moodie, Tom Blanton, Monika Borbely, David Bortnik, Malcolm Byrne, Nedialka Douptcheva, Johanna Felcser, Drew Gilbert, Christiaan Hetzner, Kevin Krogman, John Martinez, Daniel Rozas, Natasha Shur, Aleksandra Szczepanowska, Robert Wampler, Vladislav Zubok. The Cold War International History Project was established at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 1991 with the help of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and receives major support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation. The Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to disseminate new information and perspectives on Cold War history emerging from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side”—the former Communist bloc—through publications, fellowships, and scholarly meetings and conferences. Within the Wilson Center, CWIHP is under the Division of International Studies, headed by Dr. Robert S. Litwak. The Director of the Cold War International History Project is Dr. David Wolff, and the incoming Acting Director is Christian F. -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 28

2013 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane H-Diplo Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Volume XIV, No. 28 (2013) Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State 22 April 2013 University Northridge Geoffrey Roberts. Molotov: Stalin’s Cold Warrior. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-1-57488-945-1 (cloth, $29.95). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XIV-28.pdf Contents Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State University Northridge ............................... 2 Review by Alexei Filitov, Institute of World History, Russian Academy of Sciences ................ 5 Review by Jonathan Haslam, Cambridge University ................................................................ 8 Review by Jochen Laufer, Potsdamer Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung ...................... 13 Review by Wilfried Loth, University of Duisburg-Essen .......................................................... 18 Author’s Response by Geoffrey Roberts, University College Cork Ireland ............................. 21 Copyright © 2013 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XIV, No. 28 (2013) Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State University Northridge emarkably, until recently Joseph Stalin’s closest aide, Vyacheslav Molotov, has rarely been the subject of serious scholarly interest. Geoffrey Roberts was one of the first R to see Molotov’s files. -

Stalin's Baku Curve: a Detonating Mixture of Crime and Revolution

Stalin’s Baku Curve: A Detonating Mixture of Crime and Revolution by Fuad Akhundov A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Education Leadership Higher and Adult Education, OISE University of Toronto © Copyright by Fuad Akhundov 2016 Stalin’s Baku Curve: A Detonating Mixture of Crime and Revolution Fuad Akhundov Master of Arts in Education Leadership Higher and Adult Education, OISE University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The Stalin’s Baku Curve, a Detonating Mix of Crime and Revolution presents a brief insight into the early period of activities of one of the most ominous political figures of the 20th century – Joseph Stalin. The major emphasis of the work is made on Stalin’s period in Baku in 1902-1910. A rapidly growing industrial hub providing almost half of the world’s crude oil, Baku was in the meantime a brewery of revolutionary ideas. Heavily imbued with crime, corruption and ethnic tensions, the whole environment provided an excellent opportunity for Stalin to undergo his “revolutionary universities” through extortion, racketeering, revolutionary propaganda and substantial incarceration in Baku’s famous Bailov prison. Along with this, the Baku period brought Stalin into close contact with the then Russian secret police, Okhranka. This left an indelible imprint on Stalin’s character and ruling style as an irremovable leader of the Soviet empire for almost three decades. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work became possible due to the tremendous input of several scholars whom I want to hereby recognize. The first person I owe the paper Stalin’s Baku Curve, a Detonating Mix of Crime and Revolution to is Simon Sebag Montefiore, an indefatigable researcher of former Soviet and pre-Soviet history whom I had a pleasure of working with in Baku back in 1995. -

Chronology of Stalin's Life

Chronology of Stalin's Life ('Old Style' to February 1918) 1879 9 Dec Born in Gori. 1888 Sept Enters clerical elementary school in Gori. 1894 Sept Enters theological seminary in Tbilisi. 1899 May Expelled from seminary. 1900 Apr Addresses worker demonstration near Tbilisi. 1902 Apr Arrested in Batumi following worker demonstration of which he was an organizer. 1903 July-Aug Appearance of Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers' Party (Stalin not present). 1904 Jan Escapes from place of exile in Siberia and returns to underground revolutionary work in Transcaucasia. 1905 Revolution, reaching peak in Oct-Dec. threatens the survival of the tsarist government. Stalin marries Ekaterina Svanidze. Dec Attends Bolshevik conference. also attended by Lenin, in Tammerfors, Finland. 1906 Apr Attends 'Unity' congress of party in Stockholm. 1907 Mar Birth of first child, Yakov. Apr Publishes first substantial piece of writing, 'Anarchism or Socialism?' Apr-May Attends party congress in London. Jun Moves operations to Baku. Oct Death of his wife, Ekaterina. 1908 Mar Arrested in Baku. 317 318 Chronology of Stalin's Life 1909 June Escapes from place of exile, Solvychegodsk, returns to underground in Baku. 1910 Mar Arrested and jailed. Oct Returned to exile in Solvychegodsk. 1911 June Police permit his legal residence in Vologda. Sept Illegally goes to St Petersburg but is arrested and returned to Vologda. 1912 Jan Bolshevik conference in Prague at which Lenin attempts to establish his control of party; Stalin not present but soon after is co-opted to new Central Committee. Apr Illegally moves to St Petersburg, but is arrested there. -

The Iron Curtain As an Aspect of the Sovietisation of Eastern Europe in 1949–1953

Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej ■ LII-SI(1) Paweł Bielicki Institute of Political Sciences, Kazimierz Wielki University The Iron Curtain as an Aspect of the Sovietisation of Eastern Europe in 1949–1953 Zarys treści: Sowietyzacja była kluczowym etapem prowadzącym do utrwalenia „żelaznej kur- tyny” na terenie Europy Wschodniej i pełnego podporządkowania krajów wschodnioeuro- pejskich Związkowi Radzieckiemu. W artykule omawiam rożne aspekty sowietyzacji, m.in. wymiar ustrojowy, gospodarczy oraz wojskowy. W ostatniej z wyżej wymienionych dziedzin pozwoliłem sobie na wyartykułowanie przyczyn, które sprawiły, że władze sowieckie pod- jęły decyzję o przeprowadzeniu przyspieszonej sowietyzacji w dziedzinie militarnej na terenie Europy Wschodniej. Ważnym elementem niniejszego artykułu jest też kwestia prześladowa- nia Kościoła w państwach zdominowanych przez ZSRR. W podsumowaniu nakreślam konse- kwencje omawianych w artykule wydarzeń dla współczesnej rzeczywistości politycznej krajów postkomunistycznych w wymiarze politycznym, gospodarczym oraz społecznym. Outline of content: Sovietisation was the key stage leading to the strengthening of the Iron Curtain sealing off Eastern Europe and to the total subjugation of Eastern European countries to the Soviet Union. In the article, the author discusses various aspects of Sovietisation, emphasising its political, economic and military aspects, including the reasons underlying the decision taken by the Soviet leaders to step up the pace of Sovietisation in the military field in Eastern Europe. An important part of the present study is also the question of the persecution of the Church in the states dominated by the USSR. In the conclusions, the author discusses the consequences of the described developments for the contemporary political situation of the post-communist countries in their political, economic and social aspects. -

The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered

Crump_PROEF (all).ps Front - 1 T1 - Black The Warsaw Pact Reconsidered Inquiries into the Evolution of an Underestimated Alliance, 1960-1969 Een nieuwe visie op het Warschaupact Een onderzoek naar de ontwikkeling van een ondergewaardeerde alliantie, 1960-1969 (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 10 januari 2014 des middags te 2.30 uur door Laura Carolien Crump geboren op 11 augustus 1978 te Amsterdam Crump_PROEF (all).ps Back - 1 T1 - Black Promotoren: Prof. dr. D.A. Hellema Prof. dr. J. Hoffenaar Crump_PROEF (all).ps Front - 2 T1 - Black To my husband Kenneth Gabreëls my most beloved ally Crump_PROEF (all).ps Back - 2 T1 - Black Cover Illustration: Foundation of the Warsaw Pact, 14 May 1955, Warsaw File: Bundesarchiv Bild 183-30483-002, Warschau, Konferenz Europäischer Länder http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-30483- 002,_Warschau,_Konferenz_Europäischer_Länder....jpg Cover Illustration (back): Map of Europe showing NATO and the Warsaw Pact (ca. 1973) http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NATO_and_the_Warsaw_Pact_1973.svg Crump_PROEF (all).ps Front - 3 T1 - Black Contents Contents Abbreviations Chronology of Events Note on Translations Introduction: Reconsidering the Warsaw Pact 1 A New Approach towards the Warsaw Pact 2 The International Constellation 5 New Cold War -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 61 “This Is Not A Politburo, But A Madhouse”1 The Post-Stalin Succession Struggle, Soviet Deutschlandpolitik and the SED: New Evidence from Russian, German, and Hungarian Archives Introduced and annotated by Christian F. Ostermann I. ince the opening of the former Communist bloc East German relations as Ulbricht seemed to have used the archives it has become evident that the crisis in East uprising to turn weakness into strength. On the height of S Germany in the spring and summer of 1953 was one the crisis in East Berlin, for reasons that are not yet of the key moments in the history of the Cold War. The entirely clear, the Soviet leadership committed itself to the East German Communist regime was much closer to the political survival of Ulbricht and his East German state. brink of collapse, the popular revolt much more wide- Unlike his fellow Stalinist leader, Hungary’s Matyas spread and prolonged, the resentment of SED leader Rakosi, who was quickly demoted when he embraced the Walter Ulbricht by the East German population much more New Course less enthusiastically than expected, Ulbricht, intense than many in the West had come to believe.2 The equally unenthusiastic and stubborn — and with one foot uprising also had profound, long-term effects on the over the brink —somehow managed to regain support in internal and international development of the GDR. By Moscow. The commitment to his survival would in due renouncing the industrial norm increase that had sparked course become costly for the Soviets who were faced with the demonstrations and riots, regime and labor had found Ulbricht’s ever increasing, ever more aggressive demands an uneasy, implicit compromise that production could rise for economic and political support. -

General Editor's Introduction These Books Attempt to Fill a Major Gap In

General Editor's Introduction These books attempt to fill a major gap in the documentary material available in English on the development of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). At present there is a substantial body of translated ideological material, based on the collected works of Lenin and Stalin, running to 72 volumes in full, but reduced to more manageable proportions in various anthologies. This is undoubtedly valuable, but it slights a large and equally important kind of documentary material that has long been readily available in Russian and emphasized in Soviet publications on the CPSU. This category may be summarized under the label 'decisions' (re- sheniia), which has had a fairly definite meaning in Russian communism since the early days of the party. The party decision as a document appears under diverse labels, principally rezoliutsiia, postanovlenie, and polozhenie, and is at least closely allied to the programma and ustav, which have equivalent or greater authority. (Not all such labels suggest any particular English translation. Rezoliutsiia is clearly 'resolution' and pro- gramma is 'programme,' but the others might be variously translated.) All decisions of the party are considered to be formal and binding expressions of the authority of the whole party; they, and not the classics of marxism- leninism, are the operating commands. Decisions that represent the party as a whole and that are binding on the entire party are always issued in the name of the party congress, conference, or Central Committee. The former two bodies scarcely differ, both being relatively large, infrequent assem- blies that purport to represent the party as a whole. -

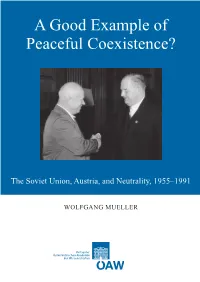

A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence?

A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence? The Soviet Union, Austria, and Neutrality, 1955–1991 WOLFGANG MUELLER WOLFGANG MUELLER A GOOD EXAMPLE OF PEACEFUL COEXISTENCE? THE SOVIET UNION, AUSTRIA, AND NEUTRALITY, 1955‒1991 ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE HISTORISCHE KOMMISSION ZENTRALEUROPA-STUDIEN HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ARNOLD SUPPAN UND GRETE KLINGENSTEIN BAND 15 WOLFGANG MUELLER A Good Example of Peaceful Coexistence? The Soviet Union, Austria, and Neutrality 1955‒1991 Vorgelegt von w. M. Arnold Suppan in der Sitzung am 18. Juni 2010 Cover: The Austrian chancellor, Julius Raab (r.), welcomes Nikita Khrushchev in his office, 30 June 1960, photograph by Fritz Kern, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek – Bildarchiv, FO504632_4_48. Cover design: Oliver Hunger British Library Cataloguing in Publication data. A Catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. Die verwendete Papiersorte ist aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff hergestellt, frei von säurebildenden Bestandteilen und alterungsbeständig. Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-7001-6898-0 Copyright © 2011 by Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest http://hw.oeaw.ac.at/6898-0 http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 9 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 13 Soviet-Austrian relations, 1945–1955 ........................................................