Reform of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts: Introducing a Public Advocate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R E P O R T Select Committee on Intelligence United

1 114TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 1st Session SENATE 114–8 R E P O R T OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE COVERING THE PERIOD JANUARY 3, 2013 TO JANUARY 5, 2015 MARCH 31, 2015.—Ordered to be printed Filed under authority of the order of the Senate of March 27 (legislative day, March 26) 2015 U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 49–010 WASHINGTON : 2015 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:43 Apr 01, 2015 Jkt 049010 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\SR008.XXX SR008 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Chairman DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California, Vice Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon DANIEL COATS, Indiana BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK R. WARNER, Virginia SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico ROY BLUNT, Missouri ANGUS S. KING, Jr., Maine JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii TOM COTTON, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio Member HARRY REID, Nevada, Ex Officio Member JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio Member JACK REED, Rhode Island, Ex Officio Member CHRIS JOYNER, JACK LIVINGSTON, Staff Directors DAVID GRANNIS, Minority Staff Director DESIREE T. SAYLE, Chief Clerk During the period covered by this report, the composition of the Select Committee on Intel- ligence was as follows: DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California, Chairman SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia, Vice Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia RICHARD BURR, North Carolina RON WYDEN, Oregon JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland DANIEL COATS, Indiana MARK UDALL, Colorado MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK R. -

Information Awareness Office

Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia Wiki Loves Monuments: Photograph a monument, help Wikipedia and win! Learn more Main page Contents Featured content Information Awareness Office Current events From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Random article Donate to Wikipedia The Information Awareness Wikipedia store Office (IAO) was established by the Interaction United States Defense Advanced Help Research Projects Agency About Wikipedia (DARPA) in January 2002 to bring Community portal together several DARPA projects Recent changes focused on applying surveillance Contact page and information technology to track Tools and monitor terrorists and other What links here asymmetric threats to U.S. national Related changes security by achieving "Total Upload file Information Awareness" Special pages (TIA).[4][5][6] Permanent link [1][2] Page information This was achieved by creating Information Awareness Office seal (motto: lat. scientia est potentia – knowledge is Wikidata item enormous computer databases to power[3]) Cite this page gather and store the personal information of everyone in the Print/export Part of a series on United States, including personal e- Create a book Global surveillance Download as PDF mails, social networks, credit card Printable version records, phone calls, medical records, and numerous other sources, without Languages any requirement for a search Català warrant.[7] This information was then Disclosures Deutsch Origins · Pre-2013 · 2013–present · Reactions analyzed to look for suspicious Français Systems activities, connections between Italiano XKeyscore · PRISM · ECHELON · Carnivore · [8] Suomi individuals, and "threats". Dishfire · Stone Ghost · Tempora · Frenchelon Svenska Additionally, the program included · Fairview · MYSTIC · DCSN · Edit links funding for biometric surveillance Boundless Informant · Bullrun · Pinwale · Stingray · SORM · RAMPART-A technologies that could identify and Agencies track individuals using surveillance NSA · BND · CNI · ASIO · DGSE · Five Eyes · [8] cameras, and other methods. -

The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

Indiana Law Journal Volume 91 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 2016 The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Emily Berman University of Houston Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, National Security Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Emily (2016) "The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 91 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol91/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court EMILY BERMAN* When former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked a massive trove of information about secret intelligence-collection programs implemented under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in the summer of 2013, U.S. surveillance activities were thrust to the forefront of public debate. This debate included the question of whether and how to reform the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (“FISA Court”), the statutorily created secret court that reviews government applications to conduct surveillance in the United States. This discussion, however, has underemphasized a critical feature of the way the FISA Court works. As this Article will show, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (“9/11”), the FISA Court has been playing not only its traditional role of “gatekeeper,” but also the additional—and entirely different—role of “rule maker.” This is the first scholarly examination of this dichotomy and its implications for reform. -

FISA and NSA Legislation Introduced In

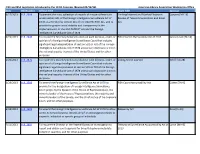

FISA and NSA Legislation Introduced in the 113th Congress (Revised 03/14/14) American Library Association Washington Office Date Bill Number Official Title Short Title Sponsor 6/17/2013 H.R. 2399 To prevent the mass collection of records of innocent Americans Limiting Internet and Blanket Electronic Conyers [MI-13] under section 501 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of Review of Telecommunications and Email 1978, as amended by section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act, and to Act provide for greater accountability and transparency in the implementation of the USA PATRIOT Act and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978. 6/19/2013 H.R. 2440 To require the Attorney General to disclose each decision, order, or FISA Court in the Sunshine Act of 2013 Jackson Lee [TX-18] opinion of a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that includes significant legal interpretation of section 501 or 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 unless such disclosure is not in the national security interest of the United States and for other purposes. 6/20/2013 H.R. 2475 To require the Attorney General to disclose each decision, order, or Ending Secret Law Act Schiff [CA-28] opinion of a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that includes significant legal interpretation of section 501 or 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 unless such disclosure is not in the national security interest of the United States and for other purposes. 6/28/2013 H.R. 2586 To amend the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 to FISA Court Accountability Act Cohen [TN-9] provide for the designation of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court judges by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the minority leader of the House of Representatives, the majority and minority leaders of the Senate, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and for other purposes. -

Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community

TILL DEATH DO US PART: PREPUBLICATION REVIEW IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY Kevin Casey* As a condition of access to classified information, most employees of the U.S. intelligence community are required to sign nondisclosure agreements that mandate lifetime prepublication review. In essence, these agreements require employees to submit any works that discuss their experiences working in the intelligence community---whether writ- ten or oral, fiction or nonfiction---to their respective agencies and receive approval before seeking publication. Though these agreements constitute an exercise of prior restraint, the Supreme Court has held them constitu- tional. This Note does not argue fororagainsttheconstitutionality of prepublication review; instead, it explores how prepublication review is actually practiced by agencies and concludes that thecurrentsystem, which lacks executive-branch-wide guidance, grants too much discretion to individual agencies. It compares the policies of individual agencies with the experiences of actual authors who have clashed with prepublication-review boards to argue that agencies conduct review in a manner that is inconsistent at best, and downright biased and discriminatory at worst. The level of secrecy shrouding intelligence agencies and the concomitant dearth of publicly available information about their activi- ties make it difcult to evaluate their performance and, by extension, the performance of our electedofcials in overseeing such activities. In such circumstances, memoirs and other forms of expression -

CR 10 12 2013 Online.Pdf

Entscheidungen und Entscheidungsprozesse der Legislative der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika Jahrgang 28, No.10-12/2013 Congress Report, Jahrgang 28 (2013), Heft 10-12 ___________________________________________________________________________ abgeschlossen am 17. Dezember 2013 Seite 1. Überbrückungshaushalt beendet Schließung von Bundesbehörden 1 2. Haushaltskompromiss zwischen Republikanern und Demokraten 3 3. Breite Kritik an mangelhafter Umsetzung von Obamas Gesundheitsreform 5 4. Senat schränkt „Filibuster“ stark ein 7 5. Steuerpolitik in unbefristeter Warteschleife 9 6. Geheimdienstausschuss des Senats für Reform der gesetzlichen Grundlagen der NSA-Aktivitäten 11 7. Uneinigkeit bei den Demokraten über weiteren Umgang mit dem Iran 15 8. Tauziehen um Defense Authorization 2014 17 9. Militärische Intervention der USA in Syrien nach Einigung über Vernichtung von Chemiewaffen vom Tisch 18 10-12/2013 Congress Report, Jahrgang 20 (2005), Heft 5 ___________________________________________________________________________ 2 Congress Report, ISSN 0935 - 7246 Nachdruck und Vervielfältigung nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung der Redaktion. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Congress Report, Jahrgang 28 (2013), Heft 10-12 ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Überbrückungshaushalt beendet Schließung von Bundesbehörden Senat und Repräsentantenhaus haben mit der Verabschiedung eines Kompromisspakets am 16. Oktober 2013 die mehr als zweiwöchige Schließung aller nicht sicherheitsrelevanten Bundesbehörden beendet. Präsident -

Reform of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts: Procedural and Operational Changes

Reform of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts: Procedural and Operational Changes Andrew Nolan Legislative Attorney Richard M. Thompson II Legislative Attorney August 26, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43362 Reform of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts: Procedural and Operational Changes Summary Recent disclosures concerning the size and scope of the National Security Agency’s (NSA) surveillance activities both in the United States and abroad have prompted a flurry of congressional activity aimed at reforming the foreign intelligence gathering process. While some measures would overhaul the substantive legal rules of the USA PATRIOT Act or other provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), there are a host of bills designed to make procedural and operational changes to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), a specialized Article III court that hears applications and grants orders approving of certain foreign intelligence gathering activities, and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review, a court that reviews rulings of the FISC. This report will explore a selection of these proposals and address potential legal questions such proposals may raise. Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matters it adjudicates, the FISC operates largely in secret and in a non-adversarial manner with the government as the only party. Some have argued that this non-adversarial process prevents the court from hearing opposing viewpoints on difficult legal issues facing the court. To address these concerns, some have suggested either permitting or mandating that the FISC hear from “friends of the court” or amici curiae, who would brief the court on potential privacy and civil liberty interests implicated by a government application. -

A Procedural Analysis of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Courts Kate

POORBAUGH.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/22/2015 10:26 AM SECURITY PROTOCOL: A PROCEDURAL ANALYSIS OF THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE COURTS KATE POORBAUGH* This Note examines proposed changes to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court following the NSA leaks by Edward Snowden. Specifically, it analyzes proposed procedural changes to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that attempt to provide a clear legal standard and effective oversight to ensure that intelligence activity does not undermine the democratic system or civil liberties. This Note argues that a public advocate should be added to FISC proceedings to represent the public’s privacy and civil liberty interests and allow FISC final orders granting surveillance to be appealed to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review by a public ad- vocate. In addition, this Note recommends that changes be made to the FISCR so that it may handle a larger caseload and become a more permanent entity with full-time judges. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1364 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 1365 A. The History of the Electronic Surveillance Law in the United States: Pre-FISA .......................................................... 1366 B. Requirements of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act . 1369 1. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court .......................... 1370 2. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review ........ -

Dynamic Surveillance: Evolving Procedures in Metadata and Foreign Content Collection After Snowden Peter Margulies

Hastings Law Journal Volume 66 | Issue 1 Article 1 12-2014 Dynamic Surveillance: Evolving Procedures in Metadata and Foreign Content Collection After Snowden Peter Margulies Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter Margulies, Dynamic Surveillance: Evolving Procedures in Metadata and Foreign Content Collection After Snowden, 66 Hastings L.J. 1 (2014). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol66/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Margulies_20 (Teixeira CORRECTED).DOC (Do Not Delete) 11/26/2014 2:21 PM Articles Dynamic Surveillance: Evolving Procedures in Metadata and Foreign Content Collection After Snowden Peter Margulies* This Article outlines a dynamic conception of national security surveillance that justifies programs disclosed by Edward Snowden but calls for greater transparency and accountability in the wake of Snowden’s revelations. The dynamic conception supports the legality of section 215 of the USA Patriot Act and section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (“FISA”), programs that received informed input from all three branches of government. Each program is part of a long democratic experiment in the integration of secrecy, deliberation, and strategic advantage that dates to the Constitution’s framing. Both programs reflect Congress’s concern that intelligence collection be sufficiently agile to keep up with evolving threats. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (“FISC”) required that both programs use technology not only to collect data, but also to prevent unduly intrusive government use of that data. -

Passage of the USA FREEDOM Act and Ending Bulk Collection Bart Forsyth

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 72 | Issue 3 Article 9 Summer 6-1-2015 Banning Bulk: Passage of the USA FREEDOM Act and Ending Bulk Collection Bart Forsyth Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Bart Forsyth, Banning Bulk: Passage of the USA FREEDOM Act and Ending Bulk Collection, 72 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1307 (2015), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol72/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Banning Bulk: Passage of the USA FREEDOM Act and Ending Bulk Collection Bart Forsyth Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................... 1308 II. Relevance under Section 215 ......................................... 1309 III. Judicial Ratification of Classified Decisions ................. 1315 IV. The Procedural History of the USA FREEDOM Act .... 1321 V. The USA FREEDOM Act’s Ban on Bulk Collection...... 1334 VI. The USA FREEDOM Act’s Ban on Bulk Collection Across Other Authorities ............................................... 1338 VII. Conclusion ...................................................................... 1340 Bart is currently serving as chief of staff to Congressman F. James Sensenbrenner. He has also served as counsel to four other House committees— the Foreign Affairs Committee, the Science and Technology Committee, the Judiciary Committee, and the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming. On the latter of which, he was also the chief of staff. -

GEORGETOWN LAW Res Ipsa Loquitur Fall/Winter 2015

GEORGETOWN LAW Res Ipsa Loquitur Fall/Winter 2015 EXPERIMENT ON K STREET Millions of Americans Can’t Afford a Lawyer The D.C. Affordable Law Firm Plans to Change That Letter from the Dean lmost 50 years ago, Georgetown University Law ACenter put law school clinics on the map. We have continued to be a leader in clinical education ever since. In the last decade we have been at the forefront of an- other landmark innovation in experiential learning as we have developed more than 30 practicum classes, which combine seminars with field placements and provide students with opportunities they can’t get anywhere else. Between our clinical offerings, our practicum and our other experiential course offerings, we can now GEORGETOWN LAW guarantee our second- and third-year law students an Fall/Winter 2015 experiential course every semester. ANNE CASSIDY Editor Another “first” may not just revolutionize legal education but the legal profession itself. Starting this September, we embarked upon a unique experiment: We are team- ANN W. PARKS Senior Writer ing up with two law firms, DLA Piper and Arent Fox, to create a new law firm that BRENT FUTRELL serves people whose incomes make them ineligible for free legal services but who can’t Director of Design afford the $200 to $300 an hour it costs to hire a lawyer in Washington, D.C. The INES HILDE Senior Designer D.C. Affordable Law Firm (see page 24) consists of six of our newly minted graduates trained to provide low bono legal services in the areas of elder law, domestic relations, EMILY ELLER Communications Associate housing, immigration and nonprofit transactional law. -

Kalanges FINAL 6-Pdfa.Pdf (311.3Kb)

Modern Private Data Collection and National Security Agency Surveillance: A Comprehensive Package of Solutions Addressing Domestic Surveillance Concerns “The advancement and diffusion of knowledge is the only guardian of true liberty.” – James Madison1 I. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………..644 II. BACKGROUND …………………………………………………...647 A. FISA AND THE 2001 PATRIOT ACT …………………………...647 B. NSA JURISPRUDENCE IN 2013: IS BULK TELEPHONY METADATA COLLECTION CONSTITUTIONAL OR UNCONSTITUTIONAL? ……………………………………….651 C. CONGRESSIONAL RESPONSE TO FISA CHALLENGES ………...654 D. LEGISLATIVE IMPACTS ON NSA POLICY …………………….656 E. THE USA FREEDOM ACT v. THE FISA IMPROVEMENTS ACT ……………………………...657 1. The USA Freedom Act: Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner …………………….657 2. The FISA Improvements Act: Senator Diane Feinstein ………………………………662 3. The First Landmark Attempt to Prompt Legislative Reform? …………………………………………….…666 III. METHODS OF SURVEILLANCE: HOW BIG IS THE BIG DATA CONNECTION? …………………………………………………...668 IV. THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION (FTC): PROVIDING POSSIBLE GUIDELINES FOR CONSTRAINTS ON FUTURE SURVEILLANCE OF U.S. CITIZENS …………………………………………………………672 V. SUGGESTIONS FOR NSA REFORM ……………………………….674 A. A COMPREHENSIVE PACKAGE FOR REMEDYING FUTURE ACTS OF SURVEILLANCE ……………………………………………..674 B. A COMPREHENSIVE PACKAGE FOR REMEDYING PAST ACTS OF SURVEILLANCE ……………………………………………..675 VI. CONCLUSION ………………………………………………….........676 1. STEVE COFFMAN, WORDS OF THE FOUNDING FATHERS: SELECTED QUOTATIONS OF FRANKLIN, WASHINGTON, ADAMS, JEFFERSON, MADISON AND HAMILTON, WITH