DEFINING REALITY AFTER SNOWDEN: a Mixed Methods Study to Global Surveillance Discourses Across Societal Sectors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance After Snowden

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183-2439) 2015, Volume 3, Issue 3, Pages 12-25 Doi: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 Article “Veillant Panoptic Assemblage”: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance after Snowden Vian Bakir School of Creative Studies and Media, Bangor University, Bangor, LL57 2DG, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 9 April 2015 | In Revised Form: 16 July 2015 | Accepted: 4 August 2015 | Published: 20 October 2015 Abstract The Snowden leaks indicate the extent, nature, and means of contemporary mass digital surveillance of citizens by their intelligence agencies and the role of public oversight mechanisms in holding intelligence agencies to account. As such, they form a rich case study on the interactions of “veillance” (mutual watching) involving citizens, journalists, intelli- gence agencies and corporations. While Surveillance Studies, Intelligence Studies and Journalism Studies have little to say on surveillance of citizens’ data by intelligence agencies (and complicit surveillant corporations), they offer insights into the role of citizens and the press in holding power, and specifically the political-intelligence elite, to account. Atten- tion to such public oversight mechanisms facilitates critical interrogation of issues of surveillant power, resistance and intelligence accountability. It directs attention to the veillant panoptic assemblage (an arrangement of profoundly une- qual mutual watching, where citizens’ watching of self and others is, through corporate channels of data flow, fed back into state surveillance of citizens). Finally, it enables evaluation of post-Snowden steps taken towards achieving an equiveillant panoptic assemblage (where, alongside state and corporate surveillance of citizens, the intelligence-power elite, to ensure its accountability, faces robust scrutiny and action from wider civil society). -

R E P O R T Select Committee on Intelligence United

1 114TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 1st Session SENATE 114–8 R E P O R T OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE COVERING THE PERIOD JANUARY 3, 2013 TO JANUARY 5, 2015 MARCH 31, 2015.—Ordered to be printed Filed under authority of the order of the Senate of March 27 (legislative day, March 26) 2015 U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 49–010 WASHINGTON : 2015 VerDate Sep 11 2014 06:43 Apr 01, 2015 Jkt 049010 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\SR008.XXX SR008 SSpencer on DSK4SPTVN1PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Chairman DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California, Vice Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho RON WYDEN, Oregon DANIEL COATS, Indiana BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK R. WARNER, Virginia SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico ROY BLUNT, Missouri ANGUS S. KING, Jr., Maine JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MAZIE K. HIRONO, Hawaii TOM COTTON, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio Member HARRY REID, Nevada, Ex Officio Member JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio Member JACK REED, Rhode Island, Ex Officio Member CHRIS JOYNER, JACK LIVINGSTON, Staff Directors DAVID GRANNIS, Minority Staff Director DESIREE T. SAYLE, Chief Clerk During the period covered by this report, the composition of the Select Committee on Intel- ligence was as follows: DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California, Chairman SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia, Vice Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia RICHARD BURR, North Carolina RON WYDEN, Oregon JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland DANIEL COATS, Indiana MARK UDALL, Colorado MARCO RUBIO, Florida MARK R. -

Mass Surveillance

Mass Surveillance Mass Surveillance What are the risks for the citizens and the opportunities for the European Information Society? What are the possible mitigation strategies? Part 1 - Risks and opportunities raised by the current generation of network services and applications Study IP/G/STOA/FWC-2013-1/LOT 9/C5/SC1 January 2015 PE 527.409 STOA - Science and Technology Options Assessment The STOA project “Mass Surveillance Part 1 – Risks, Opportunities and Mitigation Strategies” was carried out by TECNALIA Research and Investigation in Spain. AUTHORS Arkaitz Gamino Garcia Concepción Cortes Velasco Eider Iturbe Zamalloa Erkuden Rios Velasco Iñaki Eguía Elejabarrieta Javier Herrera Lotero Jason Mansell (Linguistic Review) José Javier Larrañeta Ibañez Stefan Schuster (Editor) The authors acknowledge and would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this report: Prof. Nigel Smart, University of Bristol; Matteo E. Bonfanti PhD, Research Fellow in International Law and Security, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Pisa; Prof. Fred Piper, University of London; Caspar Bowden, independent privacy researcher; Maria Pilar Torres Bruna, Head of Cybersecurity, Everis Aerospace, Defense and Security; Prof. Kenny Paterson, University of London; Agustín Martin and Luis Hernández Encinas, Tenured Scientists, Department of Information Processing and Cryptography (Cryptology and Information Security Group), CSIC; Alessandro Zanasi, Zanasi & Partners; Fernando Acero, Expert on Open Source Software; Luigi Coppolino,Università degli Studi di Napoli; Marcello Antonucci, EZNESS srl; Rachel Oldroyd, Managing Editor of The Bureau of Investigative Journalism; Peter Kruse, Founder of CSIS Security Group A/S; Ryan Gallagher, investigative Reporter of The Intercept; Capitán Alberto Redondo, Guardia Civil; Prof. Bart Preneel, KU Leuven; Raoul Chiesa, Security Brokers SCpA, CyberDefcon Ltd.; Prof. -

Information Awareness Office

Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia Wiki Loves Monuments: Photograph a monument, help Wikipedia and win! Learn more Main page Contents Featured content Information Awareness Office Current events From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Random article Donate to Wikipedia The Information Awareness Wikipedia store Office (IAO) was established by the Interaction United States Defense Advanced Help Research Projects Agency About Wikipedia (DARPA) in January 2002 to bring Community portal together several DARPA projects Recent changes focused on applying surveillance Contact page and information technology to track Tools and monitor terrorists and other What links here asymmetric threats to U.S. national Related changes security by achieving "Total Upload file Information Awareness" Special pages (TIA).[4][5][6] Permanent link [1][2] Page information This was achieved by creating Information Awareness Office seal (motto: lat. scientia est potentia – knowledge is Wikidata item enormous computer databases to power[3]) Cite this page gather and store the personal information of everyone in the Print/export Part of a series on United States, including personal e- Create a book Global surveillance Download as PDF mails, social networks, credit card Printable version records, phone calls, medical records, and numerous other sources, without Languages any requirement for a search Català warrant.[7] This information was then Disclosures Deutsch Origins · Pre-2013 · 2013–present · Reactions analyzed to look for suspicious Français Systems activities, connections between Italiano XKeyscore · PRISM · ECHELON · Carnivore · [8] Suomi individuals, and "threats". Dishfire · Stone Ghost · Tempora · Frenchelon Svenska Additionally, the program included · Fairview · MYSTIC · DCSN · Edit links funding for biometric surveillance Boundless Informant · Bullrun · Pinwale · Stingray · SORM · RAMPART-A technologies that could identify and Agencies track individuals using surveillance NSA · BND · CNI · ASIO · DGSE · Five Eyes · [8] cameras, and other methods. -

1 Collect It All: Everyday Lives Turned Into Passive Signals Intelligence

GCHQ and UK Mass Surveillance Chapter 1 1 Collect it all: everyday lives turned into passive signals intelligence 1.1 Introduction The NSA and GCHQ have stated their desire to “collect all the signals, all the time”.i To fulfil this aim, they want the ability to collect all data generated by our daily use of the Internet, phones and other technology. Through the wiretapping of international fibre optic cables, the communications of billions of people are intercepted every day. These include our personal phone calls, emails, text messages and web searches. The information provided by these communications can be broadly split into the actual content of the communication and the communications data, also called metadata, the information on when, where and to whom it was communicated. GCHQ collects both the content of communications, what is being said, and the metadata of communications. Traditionally metadata collection was perceived as less intrusive than the interception of content – reading the envelope was not as bad as opening and reading the letter. But nowadays it is widely acknowledged that metadata can provide an intimate picture of an individual’s life. We can map social relationships and traveling patterns just from metadata, without anyone looking at the contents of messages. At present, content and communications data are treated differently under the law but they can both be used to gain intrusive insights into our life. As well as collecting our personal communications data, GCHQ and the NSA have programmes that can collect data from apps, web cams and social media. The data we 1 of 16 GCHQ and UK Mass Surveillance generate will proliferate as more and more household products, from cars to fridges, use digital technology. -

SSO Corporate Portfolio Overview

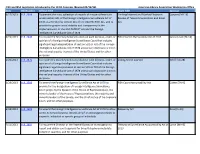

SSO Corporate Portfolio Overview Derived From: NSA/CSSM 1-52 Dated: 20070108 Declassify On: 20361201 What is SSO's Corporate Portfolio? What data can we collect? Where do I go for more help? Agenda 2 What is SSO's Corporate Portfolio? What is SSO Corporate access collection? (TS//SI//NF) Access and collection of telecommunications on cable, switch network, and/or routers made possible by the partnerships involving NSA and commercial telecommunications companies. 3 Brief discussion of global telecommunications infrastructure. How access points in the US can collect on communications from "bad guy" countries (least cost routing, etc.) 4 Unique Aspects Access to massive amounts of data Controlled by variety of legal authorities Most accesses are controlled by partner Tasking delays (TS//SI//NF) Key Points: 1) SSO provides more than 80% of collection for NSA. SSO's Corporate Portfolio represents a large portion of this collection. 2) Because of the partners and access points, the Corporate Portfolio is governed by several different legal authorities (Transit, FAA, FISA, E012333), some of which are extremely time-intensive. 3) Because of partner relations and legal authorities, SSO Corporate sites are often controlled by the partner, who filters the communications before sending to NSA. 4) Because we go through partners and do not typically have direct access to the systems, it can take some time for OCTAVE/UTT/Cadence tasking to be updated at site (anywhere from weekly for some BLARNEY accesses to a few hours for STORMBREW). 5 Explanation of how we can collect on a call between (hypothetically) Iran and Brazil using Transit Authority. -

The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

Indiana Law Journal Volume 91 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 2016 The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Emily Berman University of Houston Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, National Security Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Emily (2016) "The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 91 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol91/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Two Faces of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court EMILY BERMAN* When former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked a massive trove of information about secret intelligence-collection programs implemented under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in the summer of 2013, U.S. surveillance activities were thrust to the forefront of public debate. This debate included the question of whether and how to reform the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (“FISA Court”), the statutorily created secret court that reviews government applications to conduct surveillance in the United States. This discussion, however, has underemphasized a critical feature of the way the FISA Court works. As this Article will show, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (“9/11”), the FISA Court has been playing not only its traditional role of “gatekeeper,” but also the additional—and entirely different—role of “rule maker.” This is the first scholarly examination of this dichotomy and its implications for reform. -

Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 42 Article 4 Number 3 Spring 2015 1-1-2015 The ewN Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment Megan Blass Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Megan Blass, The New Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment, 42 Hastings Const. L.Q. 577 (2015). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol42/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New Data Marketplace: Protecting Personal Data, Electronic Communications, and Individual Privacy in the Age of Mass Surveillance Through a Return to a Property-Based Approach to the Fourth Amendment by MEGAN BLASS* I. Mass Surveillance in the New Millennium: Edward Snowden Versus The National Security Agency A. Watergate Fears Realized: National Security Agency Programs Exposed in 2013 Edward Snowden is now a household name.' He garnered global attention in 2013 when he claimed responsibility for leaking government documents that revealed unprecedented levels of domestic surveillance conducted by the National Security Agency ("NSA" or "the Agency"). 2 The information leaked by Mr. -

FISA and NSA Legislation Introduced In

FISA and NSA Legislation Introduced in the 113th Congress (Revised 03/14/14) American Library Association Washington Office Date Bill Number Official Title Short Title Sponsor 6/17/2013 H.R. 2399 To prevent the mass collection of records of innocent Americans Limiting Internet and Blanket Electronic Conyers [MI-13] under section 501 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of Review of Telecommunications and Email 1978, as amended by section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act, and to Act provide for greater accountability and transparency in the implementation of the USA PATRIOT Act and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978. 6/19/2013 H.R. 2440 To require the Attorney General to disclose each decision, order, or FISA Court in the Sunshine Act of 2013 Jackson Lee [TX-18] opinion of a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that includes significant legal interpretation of section 501 or 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 unless such disclosure is not in the national security interest of the United States and for other purposes. 6/20/2013 H.R. 2475 To require the Attorney General to disclose each decision, order, or Ending Secret Law Act Schiff [CA-28] opinion of a Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court that includes significant legal interpretation of section 501 or 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 unless such disclosure is not in the national security interest of the United States and for other purposes. 6/28/2013 H.R. 2586 To amend the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 to FISA Court Accountability Act Cohen [TN-9] provide for the designation of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court judges by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the minority leader of the House of Representatives, the majority and minority leaders of the Senate, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and for other purposes. -

Fiff-Kommunikation 4/2015

Britta Schinzel NGOs – wir klagen an und fordern auf Das Projekt 11 TAGE berührt die Intentionen des FIfF und anderer gegen Überwachung, Cyberwar und Drohnenkrieg agitierender NGOs auf vielfältige Weise. Der virtuelle Angriff auf die Ratte aus dem Internet simuliert die Drohnen-Zielfindung; das von Florian Mehnert verwendete Mittel von Egoshootern aus der Spielewelt verweist auf die Vermischung der Gamification mit dem Training an modernen Waffensystemen; die Überwachung ist essentieller Teil von Cyberwar und Drohnenkrieg. Nicht zuletzt sind auch die gegen Mehnert instanziierten Shitstorms und Morddrohungen wichtige Themen für NGOs, die sich mit dem IT-Bereich beschäftigen. Hier werden einige dieser Punkte aufgegriffen. Einleitung kontrollstation in Nähe zum Einsatzgebiet, von wo aus er mit- tels Sichtdatenlink kontrolliert wird, und einer Satelliten-Kom- Es scheint zunehmend nötig, gegen Krieg, Waffenproduktion, munikationsverbindung für Operationen ausser Sichtweite. In und Überwachung zu agitieren, gesellschaftliches Bewusstsein der Bodenkontrollstation sitzt ein Pilot, der das System fern- schwerpunkt herzustellen bzw. zu schärfen, mehr noch, Einfluss auf Parla- steuert und auf der Militärbasis in Nevada oder Ramstein im mentarier und die Regierung zu nehmen und sogar Verfassungs- Pfälzerwald2 vor ihren Bildschirmen 2 Sensoroperatoren zur klagen anzustrengen. Bedienung der Kameras, Sensoren und Radare, und für die Datenanalyse und Kommunikation. Das Fluggerät besitzt ein Wer kann in einer Demokratie außerparlamentarisch Einfluss auf Multispektral-Zielsystem, eine TV-Kamera und eine thermo- die Politik nehmen? graphische Kamera, die volle Bewegungsvideos produzieren. Es kann bis zu 14 Stunden in der Luft bleiben, bis zu 15 km hoch Solche Akteure sind einmal die Medien, zum anderen die Wis- fliegen, in einem Einsatzradius von 750 km und zurück zur Ba- senschaften mit Veröffentlichungen, und wie im vorliegenden sis. -

By Gil Carlson

No longer is there a separation between Earthly technology, other worldly technology, science fiction stories of our past, hopes and aspirations of the future, our dimension and dimensions that were once inaccessible, dreams and nightmares… for it is now all the same! By Gil Carlson (C) Copyright 2016 Gil Carlson Wicked Wolf Press Email: [email protected] To discover the rest of the books in this Blue Planet Project Series: www.blue-planet-project.com/ -1- Air Hopper Robot Grasshopper…7 Aqua Sciences Water from Atmospheric Moisture…8 Avatar Program…9 Biometrics-At-A-Distance…9 Chembot Squishy SquishBot Robots…10 Cormorant Submarine/Sea Launched MPUAV…11 Cortical Modem…12 Cyborg Insect Comm System Planned by DARPA…13 Cyborg Insects with Nuclear-Powered Transponders…14 EATR - Energetically Autonomous Tactical Robot…15 EXACTO Smart Bullet from DARPA…16 Excalibur Program…17 Force Application and Launch (FALCON)…17 Fast Lightweight Autonomy Drones…18 Fast Lightweight Autonomous (FLA) indoor drone…19 Gandalf Project…20 Gremlin Swarm Bots…21 Handheld Fusion Reactors…22 Harnessing Infrastructure for Building Reconnaissance (HIBR) project…24 HELLADS: Lightweight Laser Cannon…25 ICARUS Project…26 InfoChemistry and Self-Folding Origami…27 Iron Curtain Active Protection System…28 ISIS Integrated Is Structure…29 Katana Mono-Wing Rotorcraft Nano Air Vehicle…30 LANdroid WiFi Robots…31 Lava Missiles…32 Legged Squad Support System Monster BigDog Robot…32 LS3 Robot Pack Animal…34 Luke’s Binoculars - A Cognitive Technology Threat Warning…34 Materials -

Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community

TILL DEATH DO US PART: PREPUBLICATION REVIEW IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY Kevin Casey* As a condition of access to classified information, most employees of the U.S. intelligence community are required to sign nondisclosure agreements that mandate lifetime prepublication review. In essence, these agreements require employees to submit any works that discuss their experiences working in the intelligence community---whether writ- ten or oral, fiction or nonfiction---to their respective agencies and receive approval before seeking publication. Though these agreements constitute an exercise of prior restraint, the Supreme Court has held them constitu- tional. This Note does not argue fororagainsttheconstitutionality of prepublication review; instead, it explores how prepublication review is actually practiced by agencies and concludes that thecurrentsystem, which lacks executive-branch-wide guidance, grants too much discretion to individual agencies. It compares the policies of individual agencies with the experiences of actual authors who have clashed with prepublication-review boards to argue that agencies conduct review in a manner that is inconsistent at best, and downright biased and discriminatory at worst. The level of secrecy shrouding intelligence agencies and the concomitant dearth of publicly available information about their activi- ties make it difcult to evaluate their performance and, by extension, the performance of our electedofcials in overseeing such activities. In such circumstances, memoirs and other forms of expression