Structural Biology and Regulation of Protein Import Into the Nucleus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

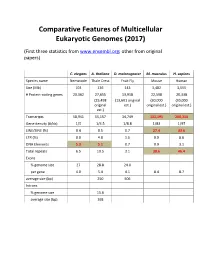

Eukaryotic Genome Annotation

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7, -

An Unusual Hydrophobic Core Confers Extreme Flexibility to HEAT Repeat Proteins

1596 Biophysical Journal Volume 99 September 2010 1596–1603 An Unusual Hydrophobic Core Confers Extreme Flexibility to HEAT Repeat Proteins Christian Kappel, Ulrich Zachariae, Nicole Do¨lker, and Helmut Grubmu¨ller* Department of Theoretical and Computational Biophysics, Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Go¨ttingen, Germany ABSTRACT Alpha-solenoid proteins are suggested to constitute highly flexible macromolecules, whose structural variability and large surface area is instrumental in many important protein-protein binding processes. By equilibrium and nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulations, we show that importin-b, an archetypical a-solenoid, displays unprecedentedly large and fully reversible elasticity. Our stretching molecular dynamics simulations reveal full elasticity over up to twofold end-to-end extensions compared to its bound state. Despite the absence of any long-range intramolecular contacts, the protein can return to its equilibrium structure to within 3 A˚ backbone RMSD after the release of mechanical stress. We find that this extreme degree of flexibility is based on an unusually flexible hydrophobic core that differs substantially from that of structurally similar but more rigid globular proteins. In that respect, the core of importin-b resembles molten globules. The elastic behavior is dominated by nonpolar interactions between HEAT repeats, combined with conformational entropic effects. Our results suggest that a-sole- noid structures such as importin-b may bridge the molecular gap between completely structured and intrinsically disordered proteins. INTRODUCTION Solenoid proteins, consisting of repeating arrays of simple on repeat proteins focus on the folding and unfolding basic structural motifs, account for >5% of the genome of mechanism (14–16), an atomic force microscopy study on multicellular organisms (1). -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Barquilla et al. 10.1073/pnas.0802668105 SI Materials and Methods The purification of recombinant GST proteins using glutathione Bioinformatics, Plasmids Constructs, and Cell Lines. Searches for T. Sepharose 4B (Amersham) was performed according to the brucei TOR, raptor, AVO3, and FKBP12 orthologues were manufacturer’s instructions and the proteins were dialyzed performed using GeneDB (www.genedb.org) and NCBI Blast against PBS. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Motif analyses were carried out using InterPro and Prosite. Antibodies. Mouse anti-TbFKBP12 monoclonal antibodies and GeneDB database accession numbers of these orthologues rabbit polyclonal anti-TOR antibodies were produced by inject- are: TbTOR1 (Tb10.6k15.2060), TbTOR2 (Tb927.4.420), ing the recombinant proteins into a BALB-C mouse or rabbit TbTOR-like 1 (Tb927.4.800), TbTOR-like 2 (Tb927.1.1930), using standard immunization protocols. Experiments involving TbRaptor (Tb11.03.0460), TbAVO3 (Tb927.8.3200), animals were approved by the National Animal Research Com- TbFKBP12 (Tb927.7.3420), and TbRaptor-like (Tb927.1.2190). mittee. Anti-TbFKBP12 antibodies were raised against the DNA fragments (400–700 bp) of the TbTOR1, TbTOR2, whole protein fused to GST, and hybridomes F12–3C7H11 and TbTOR-like 1, TbRaptor, TbAVO3, TbFKBP12, and TbRaptor- F12–7D10 H8 were selected by standard monoclonal selection like were amplified by PCR using pairs of specific primers (Table procedures as anti-TbFKBP12 monoclonal antibody producers. S1) and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega). All constructs were Anti-TbTOR antibodies were raised against nonhomologous sequenced to confirm that the subcloned DNA fragments had no TbTOR CЈ-terminal regions between the kinase domain and the mutations. -

'Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2008 Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds Parmeggiani, F Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-4818 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Parmeggiani, F. Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds. 2008, University of Zurich, Faculty of Medicine. Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Fabio Parmeggiani aus Italien Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Andreas Plückthun (Leitung der Dissertation) Prof. Dr. Markus Grütter Prof. Dr. Donald Hilvert Zürich, 2008 To my grandfather, who showed me the essence of curiosity “It is easy to add more of the same to old knowledge, but it is difficult to explain the new” Benno Müller-Hill Table of Contents 1 Table of contents Summary 3 Chapter 1: Peptide binders 7 Part I: Peptide binders 8 Modular interaction domains as natural peptide binders 9 SH2 domains 10 PTB domains 10 PDZ domains 12 14-3-3 domains 12 SH3 domains 12 WW domains 12 Peptide recognition by major histocompatibility complexes 13 Repeat proteins targeting peptides 15 Armadillo repeat proteins 16 Tetratricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR) 16 Beta propellers 16 Peptide binding by antibodies 18 Alternative scaffolds: a new approach to peptide binding 20 Part -

Dissecting and Reprogramming the Folding and Assembly of Tandem-Repeat Proteins

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Dissecting and reprogramming the folding and assembly of tandem-repeat proteins Pamela J.E. Rowling1, Elin M. Sivertsson1, Albert Perez-Riba1, Ewan R. G. Main2*, Laura S. Itzhaki1* 1University of Cambridge Department of Pharmacology, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1PD, UK. 2School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, London E1 4NS, UK. *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] and [email protected] Studying protein folding and protein design in globular proteins presents significant challenges because of the two related features, topological complexity and cooperativity. In contrast, tandem-repeat proteins have regular and modular structures composed of linearly arrayed motifs. This means that the biophysics of even giant repeat proteins is highly amenable to dissection and to rational design. Here we discuss what has been learnt about the folding mechanisms of tandem- repeat proteins. The defining features that have emerged are: (i) accessibility of multiple distinct routes between denatured and native states, both at equilibrium and under kinetic conditions; (ii) different routes are favoured for folding versus unfolding; (iii) unfolding energy barriers are broad, reflecting stepwise unraveling of an array repeat by repeat; (iv) highly cooperative unfolding at equilibrium and the potential for exceptionally high thermodynamic stabilities by introducing consensus residues; (v) under force, helical-repeat structures are very weak with non-cooperative unfolding leading to elasticity and buffering effects. This level of understanding should enable us to create repeat proteins with made-to-measure folding mechanisms, in which one can dial into the sequence the order of repeat folding, number of pathways taken, step size (cooperativity) and fine-structure of the kinetic energy barriers. -

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017)

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Appub0358.Pdf

Journal of Structural Biology 185 (2014) 147–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yjsbi Designing protein function Modular peptide binding: From a comparison of natural binders to designed armadillo repeat proteins ⇑ Christian Reichen, Simon Hansen, Andreas Plückthun Department of Biochemistry, University of Zurich, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Several binding scaffolds that are not based on immunoglobulins have been designed as alternatives to Available online 3 August 2013 traditional monoclonal antibodies. Many of them have been developed to bind to folded proteins, yet cel- lular networks for signaling and protein trafficking often depend on binding to unfolded regions of pro- Keywords: teins. This type of binding can thus be well described as a peptide–protein interaction. In this review, we Protein engineering compare different peptide-binding scaffolds, highlighting that armadillo repeat proteins (ArmRP) offer an Libraries attractive modular system, as they bind a stretch of extended peptide in a repeat-wise manner. Instead of Proteomics generating each new binding molecule by an independent selection, preselected repeats – each comple- Protein design mentary to a piece of the target peptide – could be designed and assembled on demand into a new pro- Repeat proteins Peptide binding tein, which then binds the prescribed complete peptide. Stacked armadillo repeats (ArmR), each typically Protein–peptide interactions consisting of 42 amino acids arranged in three a-helices, build an elongated superhelical structure which enables binding of peptides in extended conformation. A consensus-based design approach, comple- mented with molecular dynamics simulations and rational engineering, resulted in well-expressed monomeric proteins with high stability. -

0.01 Sequence Description Accession #Fold Change P-Value Solute Carrier Fa

FD WT untreated with DMH versus FA WT untreated p <0.01 Sequence Description Accession #Fold Change P-value Solute carrier family 9 (sodium/hydrogen exchanger),NM_016981 member -1.180931 0.00071 RIKEN cDNA 4933433P14 gene NM_178613 1.18204 0.00021 BTB (POZ) domain containing 15 NM_172765 -1.18226 0.00048 CDNA sequence BC012278 NM_146231 1.18552 0.00035 CDNA sequence BC052040 NM_207264 1.18811 0.00073 Unknown -1.18918 0.00083 Transmembrane protein 45b NM_144936 -1.19374 0.001 Zinc finger, matrin type 5 NM_026015 -1.19969 0.00027 T-complex 11 (mouse) like 2 NM_146008 -1.19983 0.00034 Villin-like U72681 -1.20146 0.00074 Zinc finger protein, multitype 1 NM_009569 1.20364 0.00028 PREDICTED: similar to ring finger and KH domainAK037256 containing 2 -1.20617 [Mus musculus], 0.00029 mRNA sequence Kinesin family member C2 NM_010630 1.20891 0.00038 RIKEN cDNA 2810407C02 gene BM945607 -1.21247 0.00022 Ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated-proteinNM_010269 2 -1.21278 0.00034 Integrator complex subunit 5 NM_176843 -1.2137 0.00037 Lectin, galactose binding, soluble 8 NM_018886 -1.21525 0.00085 WSB-2 protein NM_021539 -1.21853 0.00011 Expressed sequence C80913 NM_011274 -1.22306 0.0002 Expressed sequence AW061290 NM_201361 -1.2266 5.22E-06 Mus musculus 2 days pregnant adult female ovaryAK054427 cDNA, RIKEN 1.22687 full-length 0.00038 enriched library, clone:E330024N10 product:unclassifiable, full insert sequence. CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 1 BC042780 -1.22753 0.0009 Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein NM_016666 -1.22758 0.00004 Chloride channel calcium activated 6 NM_207208 1.22912 0.00051 SAPS domain family, member 3 NM_029456 -1.22952 0.00042 ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, beta 1 polypeptideNM_009721 -1.22954 0.00004 Mus musculus zinc finger protein 120 (Zfp120),NM_181267 transcript variant1.2304 3, mRNA. -

Table S5.Xlsx

Table S5. List of PFAM domains identified in predicted V. nonalfalfae secretome PFAM description PFAM ID Number of hits EFFECTOR-SPECIFIC PFAM 66 Calcineurin-like phosphoesterase PF00149 6 Cerato-platanin PF07249 2 CFEM (Common in Fungal Extracellular Membranes) domain PF05730 13 Chitin recongnition protein PF00187 1 Chitin recongnition protein PF03067 3 CVNH (Cyanovirin-N) domain PF08881 2 Cysteine-rich secretory protein family PF00188 4 Fungal hydrophobin PF06766 4 LysM domain PF01476 9 Lytic transglycolase PF03330 3 Necrosis inducing protein (NPP1) PF05630 6 PAN domain PF00024 1 Hce2 (Homologs of C. -

Folding and Stability of Ankyrin Repeats Control Biological Protein Function

biomolecules Review Folding and Stability of Ankyrin Repeats Control Biological Protein Function Amit Kumar 1,2,* and Jochen Balbach 2,3,* 1 Department of Life Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine London, South Kensington, London SW7 2BU, UK 2 Institute of Physics, Biophysics, Martin Luther University Halle–Wittenberg, 06120 Halle, Germany 3 Institute of Technical Biochemistry e.V. and Centre for Structure und Dynamics of Proteins, Martin Luther University Halle–Wittenberg, 06120 Halle, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (J.B.); Tel.: +44-(0)20-7594-5315 (A.K.); +49-34-5552-8550 (J.B.) Abstract: Ankyrin repeat proteins are found in all three kingdoms of life. Fundamentally, these proteins are involved in protein-protein interaction in order to activate or suppress biological pro- cesses. The basic architecture of these proteins comprises repeating modules forming elongated structures. Due to the lack of long-range interactions, a graded stability among the repeats is the generic properties of this protein family determining both protein folding and biological function. Protein folding intermediates were frequently found to be key for the biological functions of re- peat proteins. In this review, we discuss most recent findings addressing this close relation for ankyrin repeat proteins including DARPins, Notch receptor ankyrin repeat domain, IκBα inhibitor of NFκB, and CDK inhibitor p19INK4d. The role of local folding and unfolding and gradual stability of individual repeats will be discussed during protein folding, protein-protein interactions, and post-translational modifications. The conformational changes of these repeats function as molecular Citation: Kumar, A.; Balbach, J. -

Supplementary Tables Table S1. List of the 121 Lung Cancer Cell Lines

Supplementary Tables Table S1. List of the 121 lung cancer cell lines screened for MAX alterations. Information about the histopathology of each cell line, and the presence of alterations at MYC and BRG1 is also included. Grey boxes indicate that no information is available. Table S2. List of genes that are up-regulated or down-regulated upon MAX reconstitution. The values represent the n-fold change in the level of gene expression of each of the lung cancer cell lines infected with the wild type MAX relative to the controls (Ø). Table S3. List of genes that are up-regulated or down-regulated upon depletion of BRG1. The values represent the n-fold change in the level of gene expression of each of the lung cancer cell lines infected with the shBRG1 relative to the controls Ø. Table S4. List of the cell lines included in Figure 5. The information about alterations at the indicated genes was obtained from different sources, as indicated. For data extracted from databases we applied the following criteria to define a mutation: i) mutations at tumor suppressor genes (BRG1, SMARCB1, MAX, ARID1A, PRBM1, and MGA) should be homozygous and predictive of truncated proteins, ii) for amplification at the MYC family of oncogenes, only very high levels of gene amplification have been considered to be positive. Other genes, related to MYC/MAX or to the SWI/SNF complex, have also been searched for alterations (i.e., ARID1B, ARID2, MXI, MXDs) but either no alterations were reported in the databases or the changes did not fulfill our selection criteria.