From the Masses to the Masses Teachers' Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for 1950S China-India History

Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghosh, Arunabh. 2017. Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History. The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3: 697-727. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41288160 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP DRAFT: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History Arunabh Ghosh ABSTRACT China-India history of the 1950s remains mired in concerns related to border demarcations and a teleological focus on the causes, course, and consequence of the war of 1962. The result is an overt emphasis on diplomatic and international history of a rather narrow form. In critiquing this narrowness, this paper offers an alternate chronology accompanied by two substantive case studies. Taken together, they demonstrate that an approach that takes seriously cultural, scientific and economic life leads to different sources and different historical arguments from an approach focused on political (and especially high political) life. Such a shift in emphasis, away from conflict, and onto moments of contact, comparison, cooperation, and competition, can contribute fresh perspectives not just on the histories of China and India, but also on histories of the Global South. Arunabh Ghosh ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese History in the Department of History at Harvard University Vikram Seth first learned about the death of “Lita” in the Chinese city of Turfan on a sultry July day in 1981. -

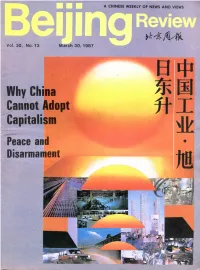

Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism

A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism Peace and Disarmament m Construction Site. Photo by Sun Chengyi Beijing HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK VOL. 30, NO. 13 MARCH 30, 1987 CONTENTS NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Macao to Return to China EVENT5AREN0S 5-9 'Sunday Engineers' Help Farmers p. 24 p. 20 Prosper Managers Receive In-Service Training Skvserapcrs Pose Problems lo Deng on the Recent Events Boning Self-Scrvice Stores: Can They • This article from the enlarged edition of Deng's Selected Survive? Works, deals with two major events — student unrest and the Energy Building in ihc Rural replacement of the Party General Secretary. In spite of these Areas events, there will be no change in the Party's line, principles and Weekly Chronicle (March 16-22) policies, says Deng (p. 33). INTERNATIONAL 10-13 Macao's Return Is Finalized Debt Problem: Mutual Compro-, • After eight months of negotiations, China and Portugal mise: the Only Way Out finally reached an agreement on the question of Macao, (Moup of 77: r.con(>niic Strategy another step towards the reunification of China (p. 4). In ihc Making Albania: Focus on Fconomic Developtnent China Spells Out Its Stand on Disarmament The United States: Weinberger s lli-Fated Visit • At a Beijing World Disarmament Campaign meeting sponsored by the UN, Chinese Vice-Foreign Minister Qian Qichen expounded China's nuclear policy and expressed the Worlfl Peace and Disarmament 14 government's concern about the spread of the arms race into NPC: Its Position and Roie 17 outer space. He also pointed out the relationship between The Election Process In Ttanjin 22 nuclear and conventional disarmament and urged the Why Capttafism is Impractical in superpowers to take the lead in all types of disarmament (p. -

Politics 110: Revolution, Socialism and “Reform” in China Winter/Spring 2021 Professor Marc Blecher

Oberlin College Department of Politics Politics 110: Revolution, Socialism and “Reform” in China Winter/Spring 2021 Professor Marc Blecher O!ice hours: Tuesdays 3:00-4:30 and Thursdays Class meets Tuesdays 11:00-12:00 Eastern Time (sign up here) and by and Thursdays, 9:30-10:50 AM appointment. Eastern Time E-mail: [email protected] on Zoom Website: tiny.cc/Blecherhome We can forgive Larson’s hapless equestrian. China has surprised so many — both its own leaders and people as well as foreign observers, including your humble professor — more often than most of them care to remember. So its recent history poses a profound set of puzzles. The Chinese Communist Party and its government, the People's Republic of China, comprise the largest surviving Communist Party-run state in the world, one of only a handful of any size. It is a rather unlikely survivor. Between 1949 and 1976, it presided over perhaps the most tempestuous of the world's state socialisms. Nowhere — not in Eastern Europe, the USSR, Cuba, Vietnam or North Korea — did anything occur like the Great Leap Forward, when the country tried to jump headlong into communism, or the Cultural Revolution, when some leaders of the socialist state called on the people Page 2 to rise up against the socialist state's own bureaucracy. Indeed, the Cultural Revolution brought China to the brink of civil war. The radical policies of the Maoist period were extremely innovative and iconoclastic, and they accomplished a great deal; but they also severely undermined the foundations of Chinese state socialism. -

China's Fear of Contagion

China’s Fear of Contagion China’s Fear of M.E. Sarotte Contagion Tiananmen Square and the Power of the European Example For the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), erasing the memory of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square massacre remains a full-time job. The party aggressively monitors and restricts media and internet commentary about the event. As Sinologist Jean-Philippe Béja has put it, during the last two decades it has not been possible “even so much as to mention the conjoined Chinese characters for 6 and 4” in web searches, so dissident postings refer instead to the imagi- nary date of May 35.1 Party censors make it “inconceivable for scholars to ac- cess Chinese archival sources” on Tiananmen, according to historian Chen Jian, and do not permit schoolchildren to study the topic; 1989 remains a “‘for- bidden zone’ in the press, scholarship, and classroom teaching.”2 The party still detains some of those who took part in the protest and does not allow oth- ers to leave the country.3 And every June 4, the CCP seeks to prevent any form of remembrance with detentions and a show of force by the pervasive Chinese security apparatus. The result, according to expert Perry Link, is that in to- M.E. Sarotte, the author of 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe, is Professor of History and of International Relations at the University of Southern California. The author wishes to thank Harvard University’s Center for European Studies, the Humboldt Foundation, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the University of Southern California for ªnancial and institutional support; Joseph Torigian for invaluable criticism, research assistance, and Chinese translation; Qian Qichen for a conversation on PRC-U.S. -

MVZ-207 Chinese Foreign Policy Since 1949

China in 1970 - 1980 MVZ-207 • Hua Goufeng Chinese Foreign Policy • Deng Xiaping • Four modernizations since 1949 • China – US relations • China – European Countries • China – Vietnam War • Normalization of FP Mgr. Jan Polišenský Spring 2011 Week 6: Independent Foreign Policy for Peace (1979 – 1988) Changes in politics Changes in politics • the reforms in beginning 80's aimed to recover • After 1979, the Chinese leadership moved toward from the crises from Mao more pragmatic positions in almost all fields • Improvement of agricultural production, • The party encouraged artists, writers, and industry, foreign trade, science, technology journalists to adopt more critical approaches, • the economical reforms replaced the the class although open attacks on party authority were struggle not permitted • the red communist Ideology faded away • In late 1980, Mao's Cultural Revolution was officially proclaimed a catastrophe • The Beijing Spring (1977 and 1978 ) brief period of political liberalization Changes in politics China entered a new age in 1979 • “Democracy Wall” in 1979 and the “fifth • The new, pragmatic leadership led by Deng modernization” Xiaoping emphasized economic development • Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun, Hu Yaobang and Zhao and renounced mass political movements Ziyang, different policy packages • Campaigns against “bourgeois spiritual contamination” and “bourgeois liberalization” 1 Democracy Wall • Long brick wall in Beijing, which became the focus for democratic dissent • Recorded news and ideas, often in the form of posters Zhang -

Chin1821.Pdf

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1x0nd955 No online items Finding Aid for the China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives, 1989-1993 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 1821 1 Descriptive Summary Title: China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives Date (inclusive): 1989-1993 Collection number: 1821 Creator: Center for Chinese Studies and the Center for Pacific Rim Studies, UCLA Extent: 22 boxes (11 linear ft.)1 oversize box. Abstract: The present finding aid represents the fruits of a multiyear collaborative effort, undertaken at the initiative of then UCLA Chancellor Charles Young, to collect, collate, classify, and annotate available materials relating to the China Democracy Movement and tiananmen crisis of 1989. These materials---including, inter alia, thousands of documents, transcribed radio broadcasts, local newspaper and journal articles, wall posters, electronic communications, and assorted ephemeral sources, some in Chinese and some in English---provide a wealth of information for scholars, present and future, who wish to gain a better understanding of the complex, swirling forces that surrounded the extraordinary "Beijing Spring" of 1989 and its tragic denouement. The scholarly community is indebted to those who have collected and arranged this archive of materials about the China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives. -

TENG%Yuning's

TENG%Yuning’s%Resume Personal)Information E"mail:([email protected] Mobile:(86"13810000598 Address(O):52(Yannan(Yuan,(Peking(University,(Beijing,(100871,(China. Tel(O):86"10"62767071 Education "( PhD(Candidate(in(Art(History(at(the(University(of(Hamburg,(Germany.(2017"( "( Master(of(Studies(in(Fine(Arts,(School(of(Arts,(Peking(University,(2005"2008() "( Bachelor( of( Arts( in( Film( and( TV( Program( Editing( and( Directing,( School( of( Arts,( Peking( University,( 2001"2005() Work)Experience ) Deputy)Director,)Centre(for(Visual(Studies(of(Peking(University,(2009"Now. Teng% works% at% Center%for%Visual%Studies%Peking%University%(CVS)% which% is% a% national% base% for% the% research% of% traditional%Chinese%art,%Chinese%contemporary%art%and%world%art%history.% As%the%deputy%director% there,%Teng ’s% main%academic%responsibility%is%managing%the%Chinese%Modern%Art%Archive%(CMAA),%which%collects%and%archives% Chinese%Contemporary%Art%dating%back%to%1986,%establishes%onIline% database,% hosts% academic% study% projects,% professional%exhibitions,%international%forums%and%seminars,%etc.% ( Executive)Editor;in;Chief,)Annual&of&Contemporary&Art&of&China,(2008"Now.(Before(that,(work)as( editor((11/2005"09/2006)(and(Director(of(Editing(Affairs,(09/2006"2008.( ( Vice)Secretary;General,(Wu(Zuoren(International(Foundation(of(Fine(Arts(WIFA),(2013"Now.( Major)Member)of)CIHA;China)Secretariat,)2012"Now,)and)Junior)Chair)of)the)Session)11,) “Landscape)and)spectacle”)of)CIHA2016,)2016.)) ) AICA)Member,)Member(of(the(International(Association(of(Art(Critics((AICA),(2018"Now) -

Mao's War on Women

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2019 Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 Al D. Roberts Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Al D., "Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976" (2019). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAO’S WAR ON WOMEN: THE PERPETUATION OF GENDER HIERARCHIES THROUGH YIN-YANG COSMOLOGY IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PROPAGANDA OF THE MAO ERA, 1949-1976 by Al D. Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Clayton Brown, Ph.D. Julia Gossard, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Li Guo, Ph.D. Dominic Sur, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________________________ Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 ii Copyright © Al D. Roberts 2019 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 by Al D. -

“China” on Display for European Audiences? the Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993)

66 “China” on Display for European Audiences? “China” on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993) Franziska Koch, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Contemporary Chinese Art–Phenomenon and Discursive Category Mediated by Exhibitions Exhibitions have always been at the heart of the modern art world and its latest developments. They are contested sites where the joint forces of art objects, their social agents, and institutional spaces intersect temporarily and provide a visual arrangement for specific audiences, whose interpretations themselves feed back into the discourse on art. Viewed from this perspective, contemporary Chinese art–as a phenomenon and as a discursive category that refer to specific dimensions of artistic production in post-1979 China– was mediated through various exhibitions that took place in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, People’s Republic). In 1989, art from the People’s Republic also began to appear in European and North American exhibitions significantly expanding Western knowledge of this artistic production. Since then, national and international exhibitions have multiplied, while simultaneously becoming increasingly entangled: the sheer number of artworks that circulate between Chinese urban art scenes and Western art metropolises has risen steeply, as have the often overlapping circles of contemporary artists, art critics, art historians, gallery owners, and collectors who successfully engage across both sides of the field. To a certain degree these agents govern exhibition-making and act as important mediators or “cultural brokers”1 globalizing the discursive category of contemporary 1 For a recent study that explores the notion of the “cultural broker” from a transcultural perspective see Rudolf G. -

How Oils Cross Oceans

ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT BEIJING SPECIAL CHINAWATCH C H INA D AIL Y How oils cross oceans Master and mentor Editor’s note: Beijing, host city of the Olympic Games in 2008, is launching a week-long culture event, from July 24 to 31, in London, to celebrate the United Kingdom’s Olympic Games. By ZHU LINYONG More than 300 artists from China will present a variety of performing arts, such as Peking Opera, acrobatics, Western classical music, an oil painting exhibition and craftworks. In addition, there will be forums on culture development and heritage preservation. Reporters from China Daily interviewed the artists and culture officials behind the project. The art of oil painting was introduced by missionaries to the Chinese court during Emperor Qianlong’s era in the middle He has taught generations of of the 18th century. The most famous was the Jesuit priest Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), known by his Chinese name young Chinese oil painters, of Lang Shining. However, the art was not widely accepted until well into the and his works are much 20th century when young Chinese started going abroad to study. Within the space of just 50 years, it had become the appreciated in China. Now, most prestigious among contemporary art forms, a status it enjoys to this day. an international audience in Oil painting became popular in the 1920s when an elite group of Chinese artists, educated in London will be able to see Europe, Japan and the United States, returned to China at about why Jin Shangyi has such a the same time. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86322-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Modern Chinese Culture Edited by Kam Louie Index More information Index Abbas, Ackbar, 310 Asian Games (1962, Indonesia), 351 abstract inheritance method, 11, 17 Asian values, 17, 151 academic research & debates Asiatic mode of production, 57–9 Chinese culture, 3 assimilation Christianity, 193 China’s peoples, 92, 95, 102, 109, 111–12 gender, 68, 71, 77, 80–2, 83 diaspora cultures, 116, 119–20, 122–3, 129, historiography, 58–61, 63–5 131 literature, 246 Australasia socialism, 193 art, 272 sociopolitical history, 38–9, 43 Chinatowns, 10 advertising, 322, 326–8 diaspora culture, 116–17, 122–4, 127–31 agriculture, 20–1, 40–1, 43, 57, 76, 159, 162, economic development, 108 166–7, 283 migrant society, 10, 16, 96 Ah Long, 223 sports, 347, 349 Air China, 323 Austro-Asiatic languages, 95, 201 Alitto, Guy, 143 Austronesian languages, 201 All China Resistance Association of Writers autonomous areas, 92–7, 99–102, 108 and Artists, 227 avant-garde All China Women’s Federation, 71, 75, 77, art, 291 80–3, 85 literature, 247–50, 251–2 Altaic languages, 201 anarchism, 27, 39, 156–63, 166 Ba Jin, 220–1 ancestor veneration, 173, 176–7, 182–3, 189 Baba culture. see peranakan Anderson, Benedict, 54 Bai people, 98–9 Anhui, 199 baihuawen. see vernacular language Appadurai, Arjun, 314–15 Bajin. see Li Feigan Apter, David, 57–8 ballroom dancing, 18, 43 Arabic language, 198 Bandung Conference (1955), 351 Arabs, 106 barbarism, 16, 49–50, 135, 284, 342 architecture, 8–9, 282, 287–8, 293 Barlow, -

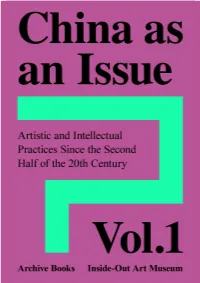

China As an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20Th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni

China as an Issue: Artistic and Intellectual Practices Since the Second Half of the 20th Century, Volume 1 — Edited by Carol Yinghua Lu and Paolo Caffoni 1 China as an Issue is an ongoing lecture series orga- nized by the Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum since 2018. Chinese scholars are invited to discuss topics related to China or the world, as well as foreign schol- ars to speak about China or international questions in- volving the subject of China. Through rigorous scruti- nization of a specific issue we try to avoid making generalizations as well as the parochial tendency to reject extraterritorial or foreign theories in the study of domestic issues. The attempt made here is not only to see the world from a local Chinese perspective, but also to observe China from a global perspective. By calling into question the underlying typology of the inside and the outside we consider China as an issue requiring discussion, rather than already having an es- tablished premise. By inviting fellow thinkers from a wide range of disciplines to discuss these topics we were able to negotiate and push the parameters of art and stimulate a discourse that intersects the arts with other discursive fields. The idea to publish the first volume of China as An Issue was initiated before the rampage of the coron- avirus pandemic. When the virus was prefixed with “China,” we also had doubts about such self-titling of ours. However, after some struggles and considera- tion, we have increasingly found the importance of 2 discussing specific viewpoints and of clarifying and discerning the specific historical, social, cultural and political situations the narrator is in and how this helps us avoid discussions that lack direction or substance.