Duke University Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for 1950S China-India History

Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghosh, Arunabh. 2017. Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History. The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 3: 697-727. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41288160 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP DRAFT: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Before 1962: The Case for 1950s China-India History Arunabh Ghosh ABSTRACT China-India history of the 1950s remains mired in concerns related to border demarcations and a teleological focus on the causes, course, and consequence of the war of 1962. The result is an overt emphasis on diplomatic and international history of a rather narrow form. In critiquing this narrowness, this paper offers an alternate chronology accompanied by two substantive case studies. Taken together, they demonstrate that an approach that takes seriously cultural, scientific and economic life leads to different sources and different historical arguments from an approach focused on political (and especially high political) life. Such a shift in emphasis, away from conflict, and onto moments of contact, comparison, cooperation, and competition, can contribute fresh perspectives not just on the histories of China and India, but also on histories of the Global South. Arunabh Ghosh ([email protected]) is Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese History in the Department of History at Harvard University Vikram Seth first learned about the death of “Lita” in the Chinese city of Turfan on a sultry July day in 1981. -

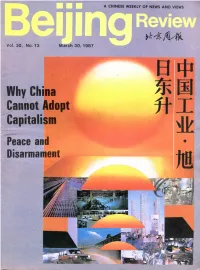

Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism

A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Why China Cannot Adopt Capitalism Peace and Disarmament m Construction Site. Photo by Sun Chengyi Beijing HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK VOL. 30, NO. 13 MARCH 30, 1987 CONTENTS NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Macao to Return to China EVENT5AREN0S 5-9 'Sunday Engineers' Help Farmers p. 24 p. 20 Prosper Managers Receive In-Service Training Skvserapcrs Pose Problems lo Deng on the Recent Events Boning Self-Scrvice Stores: Can They • This article from the enlarged edition of Deng's Selected Survive? Works, deals with two major events — student unrest and the Energy Building in ihc Rural replacement of the Party General Secretary. In spite of these Areas events, there will be no change in the Party's line, principles and Weekly Chronicle (March 16-22) policies, says Deng (p. 33). INTERNATIONAL 10-13 Macao's Return Is Finalized Debt Problem: Mutual Compro-, • After eight months of negotiations, China and Portugal mise: the Only Way Out finally reached an agreement on the question of Macao, (Moup of 77: r.con(>niic Strategy another step towards the reunification of China (p. 4). In ihc Making Albania: Focus on Fconomic Developtnent China Spells Out Its Stand on Disarmament The United States: Weinberger s lli-Fated Visit • At a Beijing World Disarmament Campaign meeting sponsored by the UN, Chinese Vice-Foreign Minister Qian Qichen expounded China's nuclear policy and expressed the Worlfl Peace and Disarmament 14 government's concern about the spread of the arms race into NPC: Its Position and Roie 17 outer space. He also pointed out the relationship between The Election Process In Ttanjin 22 nuclear and conventional disarmament and urged the Why Capttafism is Impractical in superpowers to take the lead in all types of disarmament (p. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution Through the Millennia

water Review Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution through the Millennia Andreas N. Angelakιs 1 , Daniele Zaccaria 2,*, Jens Krasilnikoff 3, Miquel Salgot 4, Mohamed Bazza 5, Paolo Roccaro 6, Blanca Jimenez 7, Arun Kumar 8 , Wang Yinghua 9, Alper Baba 10, Jessica Anne Harrison 11, Andrea Garduno-Jimenez 12 and Elias Fereres 13 1 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion and Union of Hellenic Water Supply and Sewerage Operators, 41222 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Land, Air, and Water Resources, University of California, California, CA 95064, USA 3 School of Culture and Society, Department of History and Classical Studies, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark; [email protected] 4 Soil Science Unit, Facultat de Farmàcia, Universitat de Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Formerly at Land and Water Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO, 00153 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Catania, 2 I-95131 Catania, Italy; [email protected] 7 The Comisión Nacional del Agua in Mexico City, Del. Coyoacán, México 04340, Mexico; [email protected] 8 Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi 110016, India; [email protected] 9 Department of Water Conservancy History, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] 10 Izmir Institute of Technology, Engineering Faculty, Department of Civil -

Analysis of the Causes of Most Chinese Private Entrepreneurs’ Retractednonparticipation in Charity Retractedleilei Zhang+ (China)

Volume 21, 2020 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Analysis of the Causes of Most Chinese Private Entrepreneurs’ RETRACTEDNonparticipation in Charity RETRACTEDLeilei Zhang+ (China) Abstract Enterprise charity is not only an important way for enterprises to fulfill their so- cial responsibility, but also related to their strategic development. However, most private entrepreneurs in China are not interested in doing charity. The purpose of this study is to explore the reasons why they do not participate in philanthropy. In-depth interviewsRETRACTED were conducted with 14 charitable and 10 non-charitable entrepreneurs in 24 cities of 12 provinces in China. By applying continuous ana- lytic induction, three-level coding with NVIVO software and comparative analy- sis, The results show that this is not due to the lack of economic strength of the enterprises, or the influence of China’s special national conditions, but because the entrepreneurs do not possess their own charity faith. It also provides a certain theoretical reference for entrepreneurs in other countries to fulfill their social responsibilities, In other words, to cultivate entrepreneurs’ sense of social respon- sibility, it is important to helpRETRACTED them establish their charitable beliefs. Keywords: Charity, Entrepreneur, China, Charitable Beliefs, Enterprise, Philanthropy + Leilei Zhang, Ph.D Staff, Office of International Affairs (OIA), National Institute of Development Administration(NIDA), China. voice: (662)727 3320-2 email: [email protected]. RETRACTEDReceived 2/22/19 – Revised 8/15/20 – Accepted 8/16/20 Volume 21, 2020 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Analysis of the Causes… | 39 Introduction Previous literature studies show that corporate charitable donations, play an important role for enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities (Carroll, 1991), and convey the sense of corporate responsibility to stakeholders, thus improving corporate reputation (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990) and achieving corporate strategic goals (Saiia, 2003). -

Emergence, Concept, and Understanding of Pan-River-Basin

HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com International Soil and Water Conservation Research 3 (2015) 253–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/iswcr Emergence, concept, and understanding of Pan-River-Basin (PRB) Ning Liu The Ministry of Water Resources, Beijing 10083, China Received 10 December 2014; received in revised form 20 September 2015; accepted 11 October 2015 Available online 4 November 2015 Abstract In this study, the concept of Pan-River-Basin (PRB) for water resource management is proposed with a discussion on the emergence, concept, and application of PRB. The formation and application of PRB is also discussed, including perspectives on the river contribution rates, harmonious levels of watershed systems, and water resource availability in PRB system. Understanding PRB is helpful for reconsidering river development and categorizing river studies by the influences from human projects. The sustainable development of water resources and the harmonization between humans and rivers also requires PRB. & 2015 International Research and Training Center on Erosion and Sedimentation and China Water and Power Press. Production and Hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Keywords: Aquatic Base System; Harmonization of humans and rivers; Pan-River-Basin; River contribution rate; Water transfer 1. Emergence of Pan-River-Basin A river basin (or watershed) is the area of land where surface water, including rain, melting snow, or ice, converges to a single point at a lower elevation, usually the exit of the basin. From the exit, the water joins another water body, such as a river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland, or the ocean. -

Catalyzing Social Investment in China

Catalyzing Social Investment in China Brooke Avory, Manager, CiYuan, BSR Adam Lane, Manager, Advisory Services, BSR November 2011 ciyuan.bsr.org About This Report This report was written by Brooke Avory and Adam Lane, with support from the following staff members from BSR’s global team: Kara Hurst, Jeremy Prepscius, Elissa Goldenberg, Cammie Erickson, and Lewis Xie. The report is based on literature and media reviews as well as interviews with individuals listed in the appendix. The authors would like to thank the interviewees and industry expert Pei Bin for her contribution. Any errors that remain are those of the authors alone. Please direct comments or questions to Brooke Avory at [email protected]. DISCLAIMER BSR publishes occasional papers as a contribution to the understanding of the role of business in society and the trends related to corporate social responsibility and responsible business practices. BSR maintains a policy of not acting as a representative of its membership, nor does it endorse specific policies or standards. The views expressed in this publication are those of its authors and do not reflect those of BSR members. ABOUT CIYUAN BSR’s three-year CiYuan (China Philanthropy Incubator) initiative builds innovative cross-sector partnerships to enhance the value of social investment in China. With guidance from international and Chinese leaders in the field, CiYuan improves the capacity of local foundations and NGOs to serve as durable and effective partners with business. Ultimately, CiYuan will integrate philanthropy with core business strategy, foster collaboration, and inspire innovation. Visit www.ciyuan.bsr.org for more information or to sign-up for the CiYuan newsletter. -

TENG%Yuning's

TENG%Yuning’s%Resume Personal)Information E"mail:([email protected] Mobile:(86"13810000598 Address(O):52(Yannan(Yuan,(Peking(University,(Beijing,(100871,(China. Tel(O):86"10"62767071 Education "( PhD(Candidate(in(Art(History(at(the(University(of(Hamburg,(Germany.(2017"( "( Master(of(Studies(in(Fine(Arts,(School(of(Arts,(Peking(University,(2005"2008() "( Bachelor( of( Arts( in( Film( and( TV( Program( Editing( and( Directing,( School( of( Arts,( Peking( University,( 2001"2005() Work)Experience ) Deputy)Director,)Centre(for(Visual(Studies(of(Peking(University,(2009"Now. Teng% works% at% Center%for%Visual%Studies%Peking%University%(CVS)% which% is% a% national% base% for% the% research% of% traditional%Chinese%art,%Chinese%contemporary%art%and%world%art%history.% As%the%deputy%director% there,%Teng ’s% main%academic%responsibility%is%managing%the%Chinese%Modern%Art%Archive%(CMAA),%which%collects%and%archives% Chinese%Contemporary%Art%dating%back%to%1986,%establishes%onIline% database,% hosts% academic% study% projects,% professional%exhibitions,%international%forums%and%seminars,%etc.% ( Executive)Editor;in;Chief,)Annual&of&Contemporary&Art&of&China,(2008"Now.(Before(that,(work)as( editor((11/2005"09/2006)(and(Director(of(Editing(Affairs,(09/2006"2008.( ( Vice)Secretary;General,(Wu(Zuoren(International(Foundation(of(Fine(Arts(WIFA),(2013"Now.( Major)Member)of)CIHA;China)Secretariat,)2012"Now,)and)Junior)Chair)of)the)Session)11,) “Landscape)and)spectacle”)of)CIHA2016,)2016.)) ) AICA)Member,)Member(of(the(International(Association(of(Art(Critics((AICA),(2018"Now) -

Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies

京都大学防災研究所年報 第 53 号 B 平成 22 年 6 月 Annuals of Disas. Prev. Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ., No. 53 B, 2010 Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies Pingping LUO*, Yousuke YAMASHIKI, Kaoru TAKARA, Daniel NOVER**, and Bin HE * Graduate School of Engineering ,Kyoto University, Japan ** University of California, Davis, USA Synopsis The flood is one of the world’s most dangerous natural disasters that cause immense damage and accounts for a large number of deaths and damage world-wide. Good flood control policies play an extremely important role in preventing frequent floods. It is well known that China has more than 5000 years history and flood control policies and measure have been conducted since the time of Yu the great and his father’s reign. Japan’s culture is similar to China’s but took different approaches to flood control. Under the high speed development of civil engineering technology after 1660, flood control was achieved primarily through the construction of dams, dykes and other structures. However, these structures never fully stopped floods from occurring. In this research, we present an overview of flood control policies, assess the benefit of the different policies, and contribute to a better understanding of flood control. Keywords: Flood control, Dujiangyan, History, Irrigation, Land use 1. Introduction Warring States Period of China by the Kingdom of Qin. It is located in the Min River in Sichuan Floods are frequent and devastating events Province, China, near the capital Chengdu. It is still worldwide. The Asian continent is much affected in use today and still irrigates over 5,300 square by floods, particularly in China, India and kilometers of land in the region. -

“China” on Display for European Audiences? the Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993)

66 “China” on Display for European Audiences? “China” on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993) Franziska Koch, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Contemporary Chinese Art–Phenomenon and Discursive Category Mediated by Exhibitions Exhibitions have always been at the heart of the modern art world and its latest developments. They are contested sites where the joint forces of art objects, their social agents, and institutional spaces intersect temporarily and provide a visual arrangement for specific audiences, whose interpretations themselves feed back into the discourse on art. Viewed from this perspective, contemporary Chinese art–as a phenomenon and as a discursive category that refer to specific dimensions of artistic production in post-1979 China– was mediated through various exhibitions that took place in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, People’s Republic). In 1989, art from the People’s Republic also began to appear in European and North American exhibitions significantly expanding Western knowledge of this artistic production. Since then, national and international exhibitions have multiplied, while simultaneously becoming increasingly entangled: the sheer number of artworks that circulate between Chinese urban art scenes and Western art metropolises has risen steeply, as have the often overlapping circles of contemporary artists, art critics, art historians, gallery owners, and collectors who successfully engage across both sides of the field. To a certain degree these agents govern exhibition-making and act as important mediators or “cultural brokers”1 globalizing the discursive category of contemporary 1 For a recent study that explores the notion of the “cultural broker” from a transcultural perspective see Rudolf G. -

How Oils Cross Oceans

ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT BEIJING SPECIAL CHINAWATCH C H INA D AIL Y How oils cross oceans Master and mentor Editor’s note: Beijing, host city of the Olympic Games in 2008, is launching a week-long culture event, from July 24 to 31, in London, to celebrate the United Kingdom’s Olympic Games. By ZHU LINYONG More than 300 artists from China will present a variety of performing arts, such as Peking Opera, acrobatics, Western classical music, an oil painting exhibition and craftworks. In addition, there will be forums on culture development and heritage preservation. Reporters from China Daily interviewed the artists and culture officials behind the project. The art of oil painting was introduced by missionaries to the Chinese court during Emperor Qianlong’s era in the middle He has taught generations of of the 18th century. The most famous was the Jesuit priest Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), known by his Chinese name young Chinese oil painters, of Lang Shining. However, the art was not widely accepted until well into the and his works are much 20th century when young Chinese started going abroad to study. Within the space of just 50 years, it had become the appreciated in China. Now, most prestigious among contemporary art forms, a status it enjoys to this day. an international audience in Oil painting became popular in the 1920s when an elite group of Chinese artists, educated in London will be able to see Europe, Japan and the United States, returned to China at about why Jin Shangyi has such a the same time. -

A2Z About China

A2Z about China CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com Agriculture & Irrigation • 1st world wide in farm output • Largest producer of Rice. Also produces Wheat, Potatos, Sorghum, Peanuts, Tea, Millet, Barley, Cotton, Oil seed, Pork, Tobacco and fish. • China accounts for 1/3rd of total fish production of world. • 15% of total area is cultivated • 13% GDP is from agriculture • 76.17% population is engaged in agriculture • Total Irrigated area 53.8 ha • Dujiangyan irrigation infrastructure built in 256 BC by the Kingdom of Qin, located in Min River in Sichun. It is still in use today to irrigate over 5,300 square kilometers of land in the he Dujiangyan along with the Zhengguo Canal in Shaanixi Privince & Lingqu Canal in Guangxi Province are known as “The three greatest hydraulic engineering projects of the Qin Dynasty • Turpan water system called as karez water system located in the Turpan Depression, Xinjiang, China is also as one of the 3 greatest water projects • China is believed to have more than 80000 Dams • The Three Gorges Dam is the world's larges power station in terms of installed capacity of 21000 MW CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com 2 Budget, Taxation & GDP • GDP US$ 9.872 Trillion • Individual Income tax highest slab 45% • Corporate Income Tax highest slab 25% • Yearly 9.79 trillion yuan • Major 8 type of taxes categorised as Income tax, Resource Tax, Special purpose tax, custom duty, property tax, Behaviour tax, Agriculture tax, Turnover tax . CA HEMANT C. LODHA www.a2z4all.com 3 Capital & Major Cities • Capital – Beijing • Major cities – Shanghai, Tianjin, Hong Kong, Chongqing, Wuhan, Harbin, Shengyang, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Xian, Changchun, Dalian.