Sending Mail Before Shabbos Aryeh Lebowitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

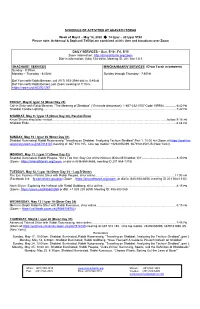

Schedule of Activities at Ahavath Torah

SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES AT AHAVATH TORAH Week of May 8 – May 14, 2020 14 Iyyar – 20 Iyyar 5780 Please note: Ashkenazi & Sephardi Tefillot are combined at this time and broadcast over Zoom DAILY SERVICES – Sun, 5/10 - Fri, 5/15 Zoom Information: http://ahavathtorah.org/zoom Dial-in information: (646) 558-8656, Meeting ID: 201 568 1315 SHACHARIT SERVICES MINCHA/MAARIV SERVICES (D’var Torah in between) Sunday - 9:00AM Monday – Thursday - 8:00AM Sunday through Thursday - 7:50PM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Berman, call (917) 553-3988 dial in, 5:45AM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Becker, join Zoom meeting at 7:10AM https://zoom.us/j/802921287 FRIDAY, May 8/ Iyyar 14 (Omer Day 29) Call-in Shiur with Rabbi Berman, “The Meaning of Shabbos” (10 minute discussion), 1-857-232-0157 Code 159954 .............. 6:42 PM Shabbat Candle Lighting ............................................................................................................................................................. 7:42 PM SHABBAT, May 9 / Iyyar 15 (Omer Day 30), Parshat Emor Kriyat Shema should be recited ....................................................................................................................................... before 9:18 AM Shabbat Ends ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8:48 PM SUNDAY, May 10 / Iyyar 16 (Omer Day 31) Shabbat Illuminated: Rabbi Rosensweig “Traveling on Shabbat: Analyzing Techum Shabbat” Part 1. 10:00 AM -

What Have We Done for God Lately

PARASHAT MATOT-MAS’EI 5772 • VOL. 2 ISSUE 41 and bizarre. Certainly if, God forbid, we were KEEP ON TRUCKIN’ – to find ourselves in a bar, we would be hard- pressed to focus on anything sacred. The only SIDEPATH WE’RE GOIN’ HOME way we can maintain a sacred focus is to have Why is there depression, sadness and faith in the teachings of genuine tzaddikim. suffering? Our Sages teach: Whoever Believing and bearing in mind that they are By Ozer Bergman mourns Jerusalem will yet share in its the ones who are fit to lead us, gives us the rejoicing (Ta’anit 30b). Without experienc- ability to follow their lead. “Moshe wrote their goings out for their ing sorrow and mourning, there is no way journeying at the word of God” (Numbers Because another reason we are in exile is to for us to appreciate its opposite. We have 33:2). “complete” the Torah. Many think that the nothing with which to compare our Trick question: What is the opposite of sinat Torah ends with the Written Torah, or the happiness. Therefore, we must experience chinam (baseless hatred)? If you said ahavat Talmud, Kabbalah, etc. Not so. The Torah is suffering. Only then can we know the true chinam (baseless love), you’re wrong. There incomplete. As history evolves and taste of joy (Crossing the Narrow Bridge). is no such thing. If there were, it would mean humankind moves closer to Utopia—the coming of Mashiach—we Jews need more loving even the most vile, violent, cruel and deadly human animals that ever disgraced and more Torah—advice and suggestions on the planet and mankind. -

Biblical and Talmudic Units of Measurement

Biblical and Talmudic units of Measurement [email protected] – י"ז אב תשע"ב Ronnie Figdor 2012 © Sources: The size of Talmudic units is a matter of controversy between: [A] R’ Chaim Naeh. Shi’urei Torah. 1947, [B] the Hazon Ish (Rabbi Avraham Ye- shayahu Karelitz 1878-1953) Moed 39: Kuntres Hashiurim and [C] R’ Moshe Feinstein (Iggerot Moshe OC I:136,YD I:107,YD I:190,YD III:46:2,YD III:66:1). See also Adin Steinsaltz. The Talmud, the Steinsaltz edition: a Reference Guide. Israel V. Berman, translator & editor NY: Random House, 1989, pp.279-293. Volume Chomer1 (dry)=kor (dry,liquid). Adriv=2letech (dry). Ephah3 (dry)=4Bat5 (liquid). Se’ah (dry)6. Arbaim Se’ah (40 se’ah), the min. quantity of kor7 8 9 10 1 11 12 water necessary for a mikveh (ritual bath), is the vol. of 1x1x3 amot . Tarkav =hin (liquid). Liquid measures include a hin, ½ hin, ∕3 hin, ¼ hin, letech 2 1 1 1 13 14 15 a log (also a dry measure), ½ log, ¼ log, ∕8 log & an ∕8 of an ∕8 log which is a kortov (liquid). Issaron (dry measure of flour)=Omer ephah 5 10 (dry) measure of grain16. Kav (dry,liquid) is the basic unit from which others are derived. Kabayim17 (dry)=2 kav. Kepiza18 (dry) se’ah 319 1512 30 1 20 21 1 22 is the min. measure required for taking Challah. Kikar (loaf)= ∕3 kav. P’ras (½ loaf ) or Perusah (broken loaf)= ∕6 kav tarkav 2 6 30 60 23 1 24 20 25 26 52 2 1 27 = 4 betzim. -

Daf Ditty Eruvin 46: the Leniency of Grief (And Eruvin)

Daf Ditty Eruvin 46: The leniency of Grief (and Eruvin) Under the wide and starry sky, Dig the grave and let me lie. Glad did I live and gladly die, And I laid me down with a will. This be the verse you grave for me: Here he lies where he longed to be; Home is the sailor, home from sea, And the hunter home from the hill. Robert Louis Stevenson 1 Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, that one who was asleep at the beginning of Shabbat may travel two thousand cubits in every direction. Rabbi Zeira said to Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi: Did you hear this halakha explicitly from Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, or did you understand it by inference from some other ruling that he issued? Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said to him: I heard it explicitly from him. 2 The Gemara asks: From what other teaching could this ruling be inferred? The Gemara explains: From that which Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv. The Gemara asks: Why do I need both? Why was it necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to state both the general ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, and also the specific ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri on this issue? Rabbi Zeira said: Both rulings were necessary, as had he informed us only that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, I would have said that the 3 halakha is in accordance with him whether this is a leniency, i.e., that a sleeping person acquires residence and may walk two thousand cubits in every direction, or whether it is a stringency, i.e., that ownerless utensils acquire residence and can be carried only two thousand cubits from that place. -

(Page Numbers from 1956 Edition of Samuch V'nireh) (211) the Train Wandered Among the Mountains

BaDerech: The Selichot Journey R' Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] Loose partial translation (page numbers from 1956 edition of Samuch v’Nireh) (211) The train wandered among the mountains, not finding its path. All of my fellow passengers departed, and I remained alone. Aside from the conductor and the engineer, no one remained. Suddenly, the train halted and did not budge. I knew that the train was over for me, and I would need to go on foot in strange places, among strange people whose language I would not know and whose ways I would not recognize. On another day this would not have pained me – just the opposite, I would have been pleased that a nice stroll had happened upon me, unexpected. But that night I was not pleased. It was the evening of Z’chor Brit; the next day would be Rosh HaShanah. How could I observe this holy day without communal prayer and without shofar? I rose from my place and looked outside. The mountains were silent; a fearsome darkness surrounded me. The conductor came and said, “Yes, sir, the train has halted and it cannot move.” He saw my pain, and he took my bag, placed it on the bench, and continued to say, “Let sir place his head upon his bag; perhaps he will sleep and gather strength, for he has a long path before him.” I nodded to him and said, “Fine, fine, sir.” I stretched out on the bench and placed my head on my bag. Before daybreak, the conductor returned. He scratched his temples and said, “Since we are far from civilization, I must wake sir from his sleep, for if he wishes to reach people before nightfall he will need to hurry.” I rose from my place and took my stick and my bag, while he showed me where to turn and where to go. -

1 a Tale of Two Cities?

A Tale of Two Cities? Shushan Purim in Modern-day Jerusalem Etan Schnall Fellow, Bella and Harry Wexner Kollel Elyon, Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, Yeshiva University I. Introduction The holiday of Purim is unique inasmuch as halacha mandates that the date of its observance varies amongst different Jewish communities. The vast majority of Jews celebrate Purim on the 14th of Adar, while Jews living in cities surrounded by walls at the time of Yehoshua bin Nun observe the 15th of Adar, known as Shushan Purim. The Talmud establishes guidelines for determining when cities receive the latter designation. In modern times, expansions of city limits have compelled Jewish legal authorities to formulate current applications of these guidelines in contemporary municipal settings. The most prominent contemporary example of a locality in question is modern-day Jerusalem and its environs, as Chazal indicate that Jerusalem was surrounded by walls at the time of Yehoshua bin Nun. The present essay will attempt to outline the issues relevant to defining the boundaries of a walled city. Following this analysis, we will present the city of Jerusalem as a case study in understanding some of the practical applications of our discussion. II. Historical Background of the Two Days of Purim The institution of Purim and Shushan Purim as two distinct commemorations traces its roots to the narrative of Megillat Esther (Chapter 9). Haman initiated a royal proclamation calling upon subjects of Achashveirosh to attack the Jewish people on the 13th of Adar. Though Haman was executed prior to this date, the decree, issued under the auspices of the king, could not be rescinded. -

Shabbat Parshat Vayetze • 6 Kislev 5771 • Nov. 13, 2010 • Vol

THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET • WWW.OHR.EDU O H R N E T SHABBAT PARSHAT VAYETZE • 6 KISLEV 5771 • NOV. 13, 2010 • VOL. 18 NO. 7 PARSHA INSIGHTS DIAMONDS THAT ARE FOREVER “And Yaakov kissed Rachel and lifted up his voice and wept.” (29:11) f you give a child a priceless Cartier necklace, he will pick The limit of honoring one’s parents is where they instruct it up and play with it. It’s bright and shiny. But after a few you to violate the will of G-d. And G-d said, “Do not Iminutes he will get bored with the necklace and start to murder”. So why did Eliphaz seek Yaakov’s advice how to play with the red velvet-lined box that the necklace came in. honor his father? Clearly, there was no mitzvah incumbent It always amazes me that children are usually much more upon Eliphaz. interested in the box than the present itself. We can see from this how great was the love of those first When it comes to mitzvot we are like children. generations for mitzvot. Even though Eliphaz had no A mitzvah is a present valuable beyond our wildest obligation to fulfill his father’s command whatsoever, Yaakov dreams. We have no idea what a mitzvah is. We have no idea of its value. spent all his money and impoverished himself so that Eliphaz “And Yaakov kissed Rachel and lifted up his voice and wept.” could fulfill the mitzvah of “Kibud Av” (honoring one’s father). -

1 on Rosh Hashana / Haazinu/Shuva

- Jewish Destiny Rabbi Berel Wein - 386 Route 59, Monsey, NY 10952 800-499-9346 and www.jewishdestiny.com for Rabbi Wein BS"D shiurim - See also http://www.yadyechiel.org/ Rabbi Frand shiurim - Keren Chasdei Shaul c/o Shulman, 632 Norfolk St, Teaneck NJ To: [email protected] 07666 From: [email protected] - Many thanks to Michael Fiskus for helping distribute Internet Parsha Sheets in Jamaica Estates. , Send donation to, Belz Institutions in Israel, c/o Michael Fiskus, 85-22 Wicklow Place, Jamaica Estates, NY 11432 This is not an all-inclusive list. See individual divrei torah for other contact information. INTERNET PARSHA SHEET _______________________________________________________ ON Rosh Hashana / Haazinu/Shuva - 5772 Rabbi Aryeh Striks [email protected] via vths.ccsend.com Mussar HaTorah Torah insights into human nature from the weekly In our 17th year! To receive this parsha sheet, go to http://www.parsha.net and click parasha. Subscribe or send a blank e-mail to [email protected] Please also copy me at Based on the talks of Rabbi A. Henach Leibowitz zt"l (Rosh [email protected] A complete archive of previous issues is now available at http://www.parsha.net It is also fully searchable. HaYeshiva of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim - RSA) and dedicated in his ________________________________________________ memory. Rosh HaShana 5772 Don't forget to prepare an Eruv Tavshilin before Yom Tov. Have a Kesiva V'Chasima Tova! Sincerely, Rabbi Aryeh Striks See pg. 8 below The Why's, How's, and What's of Eruv Tavshillin By Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff Valley Torah High School ________________________________________________ ―On that day a great Shofar will sound...‖ (Musaf) Rosh HaShana. -

Good Shabbos» Across the Easement from the Rich Home, 7303 William- » Hilchos Niddah for Men with Rabbi Yaakov Rich (Mon

CONGREGATION TORAS CHAIM An intimate space…Grow at your pace. May 27-28, 2011 . 24 Iyar, 5771 . Shabbos Parshas Bamidbar, 39 in the Omer Candlelighting: See Below . Shabbos Ends 9:13 PM Kiddush this Shabbos is sponsored by David & Lesley Wiseman, in honor of their wedding anniversary, Michael’s graduation from college, and Jennifer’s graduation from high school. Shalosh Seudos this Shabbos is sponsored by the shul. Please contact Rabbi Yaakov Rich at 972-835-6016 if you are interested in sponsoring kiddush or shalosh seudos in the future. SHABBOS SCHEDULE: » Ruth bat Leah (Grandmother of Abigail Ruttenberg) May 27th » Moshe ben Rivka (Friend of David Wiseman) » Mincha/Kabbalos Shabbos/Maariv–7:00 PM » Ceti bas Mazel (Grandmother of Ceci Katz) » Candlelighting– Preferably light by 7:25 PM. In case of great » Levi Yitzchak ben Tzirel (Friend of Rivka Krasnoff) need on may rely on 8:09 PM candlelighting time. » Gil ben Leebee (Friend of Naomi Goldberg) May 28th » Rafael Eliezer ben Leah (Friend of Abigail Ruttenberg) » Shacharis–8:30 AM » Yechiel Mordechai ben Devorah (Brother of Ken Jarmel) » “Mommy & Me” Childcare: Children with their mothers are wel- » Dina bas Chava (Friend of Josh Mann) come to spend quality time in the Katz home (Directly across the » Baruch Tzadik ben Chava (Relative of Jill Lichtenstein) easement from the Rich home, 7303 Williamswood). Please enter through the back door.–10 AM until end of davening. FATHERLY GUIDANCE: BY RABBI LABEL LAM » Chumash Shiur (for men & women)–6:45 PM These are the offspring of Aaron and Moshe on the day HASHEM » Mincha/Shalosh Seudos(for m & w) – 7:45 PM spoke with Moshe at Mount Sinai. -

Living the Halachic Process Volume VI

Living the Halachic Process Volume VI LIVING THE HALACHIC PROCESS QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS FOR THE MODERN JEW Volume VI Answers to Queries sent to the ERETZ HEMDAH INSTITUTE Headed by Rabbi Yosef Carmel Rabbi Moshe Ehrenreich by Rabbi Daniel Mann Living the Halachic Process, Vol. VI Eretz Hemdah Institute © Eretz Hemdah Institute 2020 Additional copies of this book and companion source sheets for the questions in the book are available at Eretz Hemdah: 2 Brurya St. P.O.B 8178 Jerusalem 9108101 Israel (972-2) 537-1485 fax (972-2) 537-9626 [email protected] www.eretzhemdah.org EDITORS: Rabbi Dr. Jonah Mann, Rabbi Menachem Jacobowitz. COPY EDITOR: Meira Mintz TYPESETTING & BOOK DESIGN: Rut Saadon and Renana Piniss COVER DESIGN: Rut Saadon with help from Creativejatin - Freepik.com הו"ל בהשתתפות המשרד לענייני דתות All rights reserved. However, since the purpose of this publication is educational, the copyright holder permits the limited reproduction of sections of this book for non-commercial educational purposes. ISBN 978-965-436-037-1, hardcover Printed in Israel In Loving Memory of ז"ל Rabbi Emanuel and Pesha Gottleib our beloved grandparents Their love for their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren was paralleled only by their love for TORAH, LEARNING, and ERETZ YISRAEL Shprintzy and Effy Dedicated to the memory of Leah and Rabbi Jacob Mann הרב יעקב ולאה מן ז"ל Quincy, Mass. Miriam and Abraham Roseman אברהם אייזיק ומרים רוזמן ז"ל Kew Gardens Hills, New York In Memory of our Beloved Parents Leonard and Molly Naider Joseph and Belle Serle May your memories serve as a blessing for your family and Klal Yisrael. -

The Philosophical Man of Faith

בס“ד Parshat Yitro 20 Shevat, 5780/February 15, 2020 Vol. 11 Num. 22 (#443) This issue is dedicated by Esther and Craig Guttmann and Family ב ד ב “ for the yahrtzeit of Clara Berglas This issue is dedicated by Helen & David Wm. Brown & Family, and Golda Brown & Harry Krakowsky & Family, ד ב “ for the yahrtzeit of David and Golda’s father, Al G. Brown The Philosophical Man of Faith Rabbi Baruch Weintraub At the beginning of our parshah, Yitro Rabbi Moshe Lichtenstein wrote in his Thus, his offspring could identify gives Moshe practical advice: instead book Moses: Envoy of G-d, Envoy of His themselves as believers in Hashem and of singlehandedly judging the people, People’ (p. 20), “Yitro is an ardent seeker be on good terms with the Israelites, but Moshe should appoint additional of metaphysical truth who totally still live among the Amalekites. judges, who will bear with him the isolates himself from action or weight of the people. Failing to do so, involvement within the world of We can now have a better appreciation Yitro warns, would cause both Moshe history.” He disengaged from life among of Yitro’s advice to Moshe. While Moshe and his newly freed nation to collapse. his peers, preferring to focus on and saw the nation reaching out to him for delve into the spiritual side of human judgment as a “demand for G-d,” and Many of our commentators have been life. judging as an exercise in hearing the puzzled as to why such a simple and word of G-d through His laws and self-evident move was not made by Our Sages drove this point home by commandments (Shemot 18:15-16), Moshe himself. -

Shabbat Beshalach 12 Shevat

Jewish Center of Teaneck 70 Sterling Place Teaneck, NJ 07666 201-833-0515 jcot.org Journeys Connections Traditions The JCOT is a member synagogue of the Orthodox Union. Rabbi Daniel Fridman Shabbat BeShalach Reb Yitz Cohen, Ritual Director 12 Shevat – 19 Shevat 5780 Rabbi Josh Levine, Baal Koreh Uri Horowitz, President Friday, February 7 5:02 PM Candles 5:05 PM Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat in Main Sanctuary Shabbat, February 8 6:45 AM Hashkama Minyan Main Sanctuary Followed by Kiddush in the Stein Auditorium 8:20 AM Rabbi Solomon and Bella Gopin Memorial Rambam Shiur: Techum Shabbat: Maintaining Community on Shabbat 9:00 AM Shacharit Services Main Sanctuary 9:00 AM Shacharit (Hodu) Sephardic / Moroccan Minyan in the Weiss Auditorium Shabbat Youth Schedule (See inside for details) Derasha: "This is my God, I Shall Beautify Him": In Tribute to Daniel Wetrin for His Masterful Work Kiddush after davening in the Stein Auditorium sponsored by Shmuel & Martina Elhadad in celebration of Shabat Shira and in honor of Shmuel’s father Shlomo Elhadad and in memory of his mother Phreha Elhadad z’l. 4:50 PM Mincha Seudah Shlishit 6:04 PM Maariv 6:12 PM Havdalah Ongoing and Upcoming Events The Dr. Joel Dennis and Mr. Ruvin Fridman Memorial Teaneck Tanach Study Group The Dr. Joel Dennis and Mr. Ruvin Fridman Memorial Teaneck Tanach Study Group meets Mondays at 7:45 PM. This Shiur will be discussing Sefer Shmuel. Shabbat Youth Schedule 9:45 -11:15 Pre-K, Kindergarten, 1st and 2nd in room 106 10:00-11:15 Mommy and Me in room 109 The Dov Nahari a’h Youth Minyan for boys and girls grades 3rd - 5th is under the leadership of our Shlichei Beit Ha-Knesset, Boaz and Raz Ben-Chorin.