1 a Tale of Two Cities?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

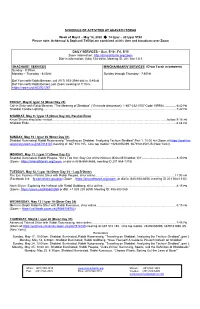

Schedule of Activities at Ahavath Torah

SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES AT AHAVATH TORAH Week of May 8 – May 14, 2020 14 Iyyar – 20 Iyyar 5780 Please note: Ashkenazi & Sephardi Tefillot are combined at this time and broadcast over Zoom DAILY SERVICES – Sun, 5/10 - Fri, 5/15 Zoom Information: http://ahavathtorah.org/zoom Dial-in information: (646) 558-8656, Meeting ID: 201 568 1315 SHACHARIT SERVICES MINCHA/MAARIV SERVICES (D’var Torah in between) Sunday - 9:00AM Monday – Thursday - 8:00AM Sunday through Thursday - 7:50PM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Berman, call (917) 553-3988 dial in, 5:45AM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Becker, join Zoom meeting at 7:10AM https://zoom.us/j/802921287 FRIDAY, May 8/ Iyyar 14 (Omer Day 29) Call-in Shiur with Rabbi Berman, “The Meaning of Shabbos” (10 minute discussion), 1-857-232-0157 Code 159954 .............. 6:42 PM Shabbat Candle Lighting ............................................................................................................................................................. 7:42 PM SHABBAT, May 9 / Iyyar 15 (Omer Day 30), Parshat Emor Kriyat Shema should be recited ....................................................................................................................................... before 9:18 AM Shabbat Ends ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8:48 PM SUNDAY, May 10 / Iyyar 16 (Omer Day 31) Shabbat Illuminated: Rabbi Rosensweig “Traveling on Shabbat: Analyzing Techum Shabbat” Part 1. 10:00 AM -

What Have We Done for God Lately

PARASHAT MATOT-MAS’EI 5772 • VOL. 2 ISSUE 41 and bizarre. Certainly if, God forbid, we were KEEP ON TRUCKIN’ – to find ourselves in a bar, we would be hard- pressed to focus on anything sacred. The only SIDEPATH WE’RE GOIN’ HOME way we can maintain a sacred focus is to have Why is there depression, sadness and faith in the teachings of genuine tzaddikim. suffering? Our Sages teach: Whoever Believing and bearing in mind that they are By Ozer Bergman mourns Jerusalem will yet share in its the ones who are fit to lead us, gives us the rejoicing (Ta’anit 30b). Without experienc- ability to follow their lead. “Moshe wrote their goings out for their ing sorrow and mourning, there is no way journeying at the word of God” (Numbers Because another reason we are in exile is to for us to appreciate its opposite. We have 33:2). “complete” the Torah. Many think that the nothing with which to compare our Trick question: What is the opposite of sinat Torah ends with the Written Torah, or the happiness. Therefore, we must experience chinam (baseless hatred)? If you said ahavat Talmud, Kabbalah, etc. Not so. The Torah is suffering. Only then can we know the true chinam (baseless love), you’re wrong. There incomplete. As history evolves and taste of joy (Crossing the Narrow Bridge). is no such thing. If there were, it would mean humankind moves closer to Utopia—the coming of Mashiach—we Jews need more loving even the most vile, violent, cruel and deadly human animals that ever disgraced and more Torah—advice and suggestions on the planet and mankind. -

מכירה מס' 28 יום רביעי י'ז שבט התש"פ 12/02/2020

מכירה מס' 28 יום רביעי י'ז שבט התש"פ 12/02/2020 1 2 בס"ד מכירה מס' 28 יודאיקה. כתבי יד. ספרי קודש. מכתבים. מכתבי רבנים חפצי יודאיקה. אמנות. פרטי ארץ ישראל. כרזות וניירת תתקיים אי"ה ביום רביעי י"ז בשבט התש"פ 12.02.2020, בשעה 19:00 המכירה והתצוגה המקדימה תתקיים במשרדנו החדשים ברחוב הרב אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק 10 בני ברק בימים: א-ג 09-11/12/2020 בין השעות 14:00-20:00 נשמח לראותכם ניתן לראות תמונות נוספות באתר מורשת www.moreshet-auctions.com טל: 03-9050090 פקס: 03-9050093 [email protected] אסף: 054-3053055 ניסים: 052-8861994 ניתן להשתתף בזמן המכירה אונליין דרך אתר בידספיריט )ההרשמה מראש חובה( https://moreshet.bidspirit.com 3 בס"ד שבט התש״פ אל החברים היקרים והאהובים בשבח והודיה לה' יתברך על כל הטוב אשר גמלנו, הננו מתכבדים להציג בפניכם את קטלוג מכירה מס' 28. בקטלוג שלפניכם ספרי חסידות מהדורת ראשונות. מכתבים נדירים מגדולי ישראל ופריטים חשובים מאוספים פרטיים: חתימת ידו של רבי אליעזר פאפו בעל הפלא יועץ זי"ע: ספר דרכי נועם עם קונטרס מלחמת מצווה מהדורה ראשונה - ונציה תנ"ז | 1697 עם חתימות נוספות והגהות חשובות )פריט מס' 160(. פריט היסטורי מיוחד: כתב שליחות )שד"רות( בחתימת המהרי"ט אלגאזי ורבני בית דינו )פריט מס' 216(. ש"ס שלם העותק של בעל ה'מקור ברוך' מסערט ויז'ניץ זצ"ל עם הערות בכתב ידו )פריט מס' 166(. תגלית: כאלף דפים של כתב היד החלק האבוד מתוך חיבורו על הרמב"ם של הגאון רבי יהודה היילברון זצ"ל )פריט מס' 194(. נדיר! כתב יד סידור גדול במיוחד עם נוסחאות והלכות נדירות - תימן תחילת המאה ה17- לערך )פריט מס' 198(. -

JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX

NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX NISSAN 5768 / APRIL 2008, VOL. 13 Green and Clean JCT Develops Solutions to Environmental Problems P.O.BOX 16031, JERUSALEM 91160 ISRAEL 91160 JERUSALEM 16031, P.O.BOX COMMENTARY JERUSALEM COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY PRESIDENT Shalom! opportunity to receive an excellent education Prof. Joseph S. Bodenheimer allowing them to become highly-skilled, ROSH HAYESHIVA Rabbi Z. N. Goldberg Of the many things sought after professionals. More important ROSH BEIT HAMIDRASH we are proud at JCT, for our students is the opportunity available Rabbi Natan Bar Chaim nothing is more RECTOR at the College to receive an education Prof. Joseph M. Steiner prized than our focusing on Jewish values. It is this DIRECTOR-GENERAL students. In every education towards values that has always Dr. Shimon Weiss VICE PRESIDENT FOR DEVELOPMENT issue of “Perspective” been the hallmark of JCT and it is this AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS we profile one of our students as a way of commitment to Jewish ethical values that Reuven Surkis showing who they are and of sharing their forms the foundation from which Israeli accomplishments with you. society will grow and flourish - and our EDITORS Our student body of 2,500 is a students and graduates take pride in being Rosalind Elbaum, Debbie Ross, Penina Pfeuffer microcosm of Israeli society: 21% are Olim committed to this process. DESIGN & PRODUCTION (immigrants) from the former Soviet Union, As we approach the Pesach holiday, the Studio Fisher Ethiopia, South America, North America, 60th anniversary of the State of Israel and JCT Perspective invites the submission of arti- Europe, Australia and South Africa, whilst the 40th anniversary of JCT, let us reaffirm cles and press releases from the public. -

THE THEOLOGICAL LETTERS of RABBI TALMUD of LUBLIN (SUMMER–FALL 1942) Gershon Greenberg

THE THEOLOGICAL LETTERS OF RABBI TALMUD OF LUBLIN (SUMMER–FALL 1942) Gershon Greenberg Carbon copies of two typewritten Hebrew letters by Rabbi Hirsh Melekh Talmud (Tsevi Elimelekh Talmud, born 1912, Glogów Małoposki) survived the Majdan- Tatarski ghetto and are held by the State Archives in Lublin. The letters offer rare access to the existential turmoil of the Jewish religious mind within the ultra-Orthodox world at the very center of the Holocaust.1 When the Germans invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Talmud―a graduate of the Hakhmei Lublin Yeshiva founded in 1924 by Meir Shapiro―was one of five functioning city rabbis of Lublin (the others were Yosef Mendel Preshisukha, Leizer Ezra Kirschenbaum, Avraham Yosef Schlingenbaum, and Yisrael Hirsch Finkelmann) and served in the civil office for marriage and burials. After the Lublin ghetto was opened in March 1941, he served on the Jewish Council (Judenrat). He was the only city rabbi to survive the March–April 1942 deportations, when most of the ghetto’s 30,000 Jews were taken to Bełżec, and was among the some 5,000 moved to the Majdan-Tatarski ghetto (established on April 19, 1942) that was situated between the Lublin ghetto and a Majdanek subcamp. He continued to serve on the Judenrat (at least through August 1942) and as a religious judge (Dayan) with responsibility for birth certificates and officiating at marriages; he also officiated at the divorce of the notorious Shammai Greier, before Greier went on to marry a seventeen-year-old girl in a raucous ceremony in the midst of the ongoing mourning. -

Volume 31, #1 (2012)

Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture Volume 31 (2012) No. 1 IN THIS ISSUE Theological and Religious Perspectives on the Internet A QUARTERLY REVIEW OF COMMUNICATION RESEARCH ISSN: 0144-4646 Communication Research Trends Table of Contents Volume 31 (2012) Number 1 http://cscc.scu.edu Editor’s Introduction . 3 Published four times a year by the Centre for the Study of Communication and Culture (CSCC), sponsored by the Jewish Cyber-Theology . 4 California Province of the Society of Jesus. 1. Introduction . 4 Copyright 2012. ISSN 0144-4646 2. The Internet and Jewish Religious Practice . 5 A. Sexual modesty . 5 Editor: Emile McAnany B. The Internet and the Sabbath . 6 Editor emeritus: William E. Biernatzki, S.J. C. e-commerce . 6 Managing Editor: Paul A. Soukup, S.J. D. The sanctity of Internet communication . 7 E. Political and social gossip on the Internet . 8 Subscription: 3. The Virtual Synagogue . 9 Annual subscription (Vol. 31) US$50 4. Online Rabbinic Counseling . 12 5. Conclusion: Future Prospects . 13 Payment by check, MasterCard, Visa or US$ preferred. For payments by MasterCard or Visa, send full account Catholic Approaches to the Internet . 14 number, expiration date, name on account, and signature. 1. Introduction . 14 2. Internet and Evangelization . 15 Checks and/or International Money Orders (drawn on 3. Ethical Issues . 16 USA banks; for non-USA banks, add $10 for handling) A. The digital divide . 17 should be made payable to Communication Research B. Community and the Internet: Trends and sent to the managing editor Social networking . 18 Paul A. Soukup, S.J. -

Biblical and Talmudic Units of Measurement

Biblical and Talmudic units of Measurement [email protected] – י"ז אב תשע"ב Ronnie Figdor 2012 © Sources: The size of Talmudic units is a matter of controversy between: [A] R’ Chaim Naeh. Shi’urei Torah. 1947, [B] the Hazon Ish (Rabbi Avraham Ye- shayahu Karelitz 1878-1953) Moed 39: Kuntres Hashiurim and [C] R’ Moshe Feinstein (Iggerot Moshe OC I:136,YD I:107,YD I:190,YD III:46:2,YD III:66:1). See also Adin Steinsaltz. The Talmud, the Steinsaltz edition: a Reference Guide. Israel V. Berman, translator & editor NY: Random House, 1989, pp.279-293. Volume Chomer1 (dry)=kor (dry,liquid). Adriv=2letech (dry). Ephah3 (dry)=4Bat5 (liquid). Se’ah (dry)6. Arbaim Se’ah (40 se’ah), the min. quantity of kor7 8 9 10 1 11 12 water necessary for a mikveh (ritual bath), is the vol. of 1x1x3 amot . Tarkav =hin (liquid). Liquid measures include a hin, ½ hin, ∕3 hin, ¼ hin, letech 2 1 1 1 13 14 15 a log (also a dry measure), ½ log, ¼ log, ∕8 log & an ∕8 of an ∕8 log which is a kortov (liquid). Issaron (dry measure of flour)=Omer ephah 5 10 (dry) measure of grain16. Kav (dry,liquid) is the basic unit from which others are derived. Kabayim17 (dry)=2 kav. Kepiza18 (dry) se’ah 319 1512 30 1 20 21 1 22 is the min. measure required for taking Challah. Kikar (loaf)= ∕3 kav. P’ras (½ loaf ) or Perusah (broken loaf)= ∕6 kav tarkav 2 6 30 60 23 1 24 20 25 26 52 2 1 27 = 4 betzim. -

Daf Ditty Eruvin 46: the Leniency of Grief (And Eruvin)

Daf Ditty Eruvin 46: The leniency of Grief (and Eruvin) Under the wide and starry sky, Dig the grave and let me lie. Glad did I live and gladly die, And I laid me down with a will. This be the verse you grave for me: Here he lies where he longed to be; Home is the sailor, home from sea, And the hunter home from the hill. Robert Louis Stevenson 1 Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said that Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, that one who was asleep at the beginning of Shabbat may travel two thousand cubits in every direction. Rabbi Zeira said to Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi: Did you hear this halakha explicitly from Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, or did you understand it by inference from some other ruling that he issued? Rabbi Ya’akov bar Idi said to him: I heard it explicitly from him. 2 The Gemara asks: From what other teaching could this ruling be inferred? The Gemara explains: From that which Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: The halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv. The Gemara asks: Why do I need both? Why was it necessary for Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi to state both the general ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the lenient opinion with regard to an eiruv, and also the specific ruling that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri on this issue? Rabbi Zeira said: Both rulings were necessary, as had he informed us only that the halakha is in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Nuri, I would have said that the 3 halakha is in accordance with him whether this is a leniency, i.e., that a sleeping person acquires residence and may walk two thousand cubits in every direction, or whether it is a stringency, i.e., that ownerless utensils acquire residence and can be carried only two thousand cubits from that place. -

The Sea of Talmud: a Brief and Personal Introduction

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2012 The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry M. Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. M. (2012). The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEA OF TALMUD A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry Abramson Published by Parnoseh Books at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Henry Abramson Cover photograph by Steven Mills. No Talmud volumes were harmed during the photo shoot for this book. Smashwords Edition, License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment and information only. This ebook should not be re-sold to others. Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute this ebook for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided the book remains in its complete original form. Version 3.1 June 18, 2012. To my students All who thirst--come to the waters Isaiah 55:1 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One: Our Talmud Chapter Two: What, Exactly, is the Talmud? Chapter Three: The Content of the Talmud Chapter Four: Toward the Digital Talmud Chapter Five: “Go Study” For Further Reading Acknowledgments About the Author Introduction The Yeshiva administration must have put considerable thought into the wording of the hand- lettered sign posted outside the cafeteria. -

Marc B. Shapiro – Responses to Comments

Marc B. Shapiro – Responses to Comments and Elaborations of Previous Posts III Responses to Comments and Elaborations of Previous Posts III by Marc B. Shapiro This post is dedicated to the memory of Rabbi Chaim Flom, late rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Ohr David in Jerusalem. I first met Rabbi Flom thirty years ago when he became my teacher at the Hebrew Youth Academy of Essex County (now known as the Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy; unfortunately, another one of my teachers from those years also passed away much too young, Rabbi Yaakov Appel). When he first started teaching he was known as Mr. Flom, because he hadn’t yet received semikhah (Actually, he had some sort of semikhah but he told me that he didn’t think it was adequate to be called “Rabbi” by the students.) He was only at the school a couple of years and then decided to move to Israel to open his yeshiva. I still remember his first parlor meeting which was held at my house. Rabbi Flom was a very special man. Just to give some idea of this, ten years after leaving the United States he was still in touch with many of the students and even attended our weddings. He would always call me when he came to the U.S. and was genuinely interested to hear about my family and what I was working on. He will be greatly missed. 1. In a previous post I showed a picture of the hashgachah given by the OU to toilet bowl cleaner. This led to much discussion, and as I indicated, at a future time I hope to say more about the kashrut industry from a historical perspective.[1] I have to thank Stanley Emerson who sent me the following picture. -

(Page Numbers from 1956 Edition of Samuch V'nireh) (211) the Train Wandered Among the Mountains

BaDerech: The Selichot Journey R' Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] Loose partial translation (page numbers from 1956 edition of Samuch v’Nireh) (211) The train wandered among the mountains, not finding its path. All of my fellow passengers departed, and I remained alone. Aside from the conductor and the engineer, no one remained. Suddenly, the train halted and did not budge. I knew that the train was over for me, and I would need to go on foot in strange places, among strange people whose language I would not know and whose ways I would not recognize. On another day this would not have pained me – just the opposite, I would have been pleased that a nice stroll had happened upon me, unexpected. But that night I was not pleased. It was the evening of Z’chor Brit; the next day would be Rosh HaShanah. How could I observe this holy day without communal prayer and without shofar? I rose from my place and looked outside. The mountains were silent; a fearsome darkness surrounded me. The conductor came and said, “Yes, sir, the train has halted and it cannot move.” He saw my pain, and he took my bag, placed it on the bench, and continued to say, “Let sir place his head upon his bag; perhaps he will sleep and gather strength, for he has a long path before him.” I nodded to him and said, “Fine, fine, sir.” I stretched out on the bench and placed my head on my bag. Before daybreak, the conductor returned. He scratched his temples and said, “Since we are far from civilization, I must wake sir from his sleep, for if he wishes to reach people before nightfall he will need to hurry.” I rose from my place and took my stick and my bag, while he showed me where to turn and where to go. -

Shabbat Parshat Vayetze • 6 Kislev 5771 • Nov. 13, 2010 • Vol

THE OHR SOMAYACH TORAH MAGAZINE ON THE INTERNET • WWW.OHR.EDU O H R N E T SHABBAT PARSHAT VAYETZE • 6 KISLEV 5771 • NOV. 13, 2010 • VOL. 18 NO. 7 PARSHA INSIGHTS DIAMONDS THAT ARE FOREVER “And Yaakov kissed Rachel and lifted up his voice and wept.” (29:11) f you give a child a priceless Cartier necklace, he will pick The limit of honoring one’s parents is where they instruct it up and play with it. It’s bright and shiny. But after a few you to violate the will of G-d. And G-d said, “Do not Iminutes he will get bored with the necklace and start to murder”. So why did Eliphaz seek Yaakov’s advice how to play with the red velvet-lined box that the necklace came in. honor his father? Clearly, there was no mitzvah incumbent It always amazes me that children are usually much more upon Eliphaz. interested in the box than the present itself. We can see from this how great was the love of those first When it comes to mitzvot we are like children. generations for mitzvot. Even though Eliphaz had no A mitzvah is a present valuable beyond our wildest obligation to fulfill his father’s command whatsoever, Yaakov dreams. We have no idea what a mitzvah is. We have no idea of its value. spent all his money and impoverished himself so that Eliphaz “And Yaakov kissed Rachel and lifted up his voice and wept.” could fulfill the mitzvah of “Kibud Av” (honoring one’s father).