Daf Ditty Eruvin 46: the Leniency of Grief (And Eruvin)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule of Activities at Ahavath Torah

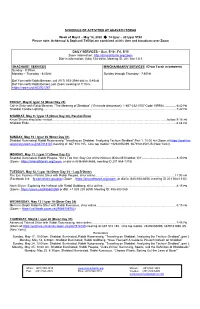

SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES AT AHAVATH TORAH Week of May 8 – May 14, 2020 14 Iyyar – 20 Iyyar 5780 Please note: Ashkenazi & Sephardi Tefillot are combined at this time and broadcast over Zoom DAILY SERVICES – Sun, 5/10 - Fri, 5/15 Zoom Information: http://ahavathtorah.org/zoom Dial-in information: (646) 558-8656, Meeting ID: 201 568 1315 SHACHARIT SERVICES MINCHA/MAARIV SERVICES (D’var Torah in between) Sunday - 9:00AM Monday – Thursday - 8:00AM Sunday through Thursday - 7:50PM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Berman, call (917) 553-3988 dial in, 5:45AM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Becker, join Zoom meeting at 7:10AM https://zoom.us/j/802921287 FRIDAY, May 8/ Iyyar 14 (Omer Day 29) Call-in Shiur with Rabbi Berman, “The Meaning of Shabbos” (10 minute discussion), 1-857-232-0157 Code 159954 .............. 6:42 PM Shabbat Candle Lighting ............................................................................................................................................................. 7:42 PM SHABBAT, May 9 / Iyyar 15 (Omer Day 30), Parshat Emor Kriyat Shema should be recited ....................................................................................................................................... before 9:18 AM Shabbat Ends ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8:48 PM SUNDAY, May 10 / Iyyar 16 (Omer Day 31) Shabbat Illuminated: Rabbi Rosensweig “Traveling on Shabbat: Analyzing Techum Shabbat” Part 1. 10:00 AM -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

The Generic Transformation of the Masoretic Text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah

Durham E-Theses Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah Hardy, John Christopher How to cite: Hardy, John Christopher (1995) Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5403/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 WINE, WOMEN AND WORK: THE GENERIC TRANSFORMATION OF THE MA50RETIC TEXT OF QOHELET 9. 7-10 IN THE TARGUM QOHELET AND QOHELET MIDRASH RABBAH John Christopher Hardy This tnesis seeks to understand the generic changes wrought oy targum Qonelet and Qoheiet raidrash rabbah upon our home-text, the masoretes' reading ot" woh. -

What Have We Done for God Lately

PARASHAT MATOT-MAS’EI 5772 • VOL. 2 ISSUE 41 and bizarre. Certainly if, God forbid, we were KEEP ON TRUCKIN’ – to find ourselves in a bar, we would be hard- pressed to focus on anything sacred. The only SIDEPATH WE’RE GOIN’ HOME way we can maintain a sacred focus is to have Why is there depression, sadness and faith in the teachings of genuine tzaddikim. suffering? Our Sages teach: Whoever Believing and bearing in mind that they are By Ozer Bergman mourns Jerusalem will yet share in its the ones who are fit to lead us, gives us the rejoicing (Ta’anit 30b). Without experienc- ability to follow their lead. “Moshe wrote their goings out for their ing sorrow and mourning, there is no way journeying at the word of God” (Numbers Because another reason we are in exile is to for us to appreciate its opposite. We have 33:2). “complete” the Torah. Many think that the nothing with which to compare our Trick question: What is the opposite of sinat Torah ends with the Written Torah, or the happiness. Therefore, we must experience chinam (baseless hatred)? If you said ahavat Talmud, Kabbalah, etc. Not so. The Torah is suffering. Only then can we know the true chinam (baseless love), you’re wrong. There incomplete. As history evolves and taste of joy (Crossing the Narrow Bridge). is no such thing. If there were, it would mean humankind moves closer to Utopia—the coming of Mashiach—we Jews need more loving even the most vile, violent, cruel and deadly human animals that ever disgraced and more Torah—advice and suggestions on the planet and mankind. -

Beitza Rosh Hashana

NOTES Rav Yosef said to Abaye: Th is is not so; rather, both according to me ֲ אַמר ֵל ּיה: ֵּבין ְלִד ִ ידי ֵּבין ְלַר ָּבה ִאית ָלן Apparently, the : ֶּׁשַיְּחפוֹר ְּבֶדֶקר – and according to Rabba we are of the opinion that the ruling is in Then he digs with a shovel conclusion is that Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagree ְּדַר ִּבי זֵ ָ ירא, ְוָהָכא ְּבָהא ָקא ַּ ִמפְלִגינַן: accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Zeira, and here we disagree over whether regular earth in a courtyard is muktze or ַר ָּבה ָסַבר, ִאי ִא ָ ּיכא ָﬠָפר ָּ ְלַמטה – with regard to this matt er: Rabba holds that if there is prepared whether it is considered prepared and may be carried and ִאין, ִאי ָלא – ָלא, ָחְי ׁ ִישינַן ִּדְלָמא earth beneath, yes, in that case one may slaughter an animal, but if used for covering (Rid). It is permitted to use the earth after there is no earth prepared beneath, no, he may not slaughter it at all. the fact, as the positive mitzva by Torah law to cover the ִמְמִל ְיך ְוָלא ָׁשֵחיט. ּוְלִד ִ ידי ( ַאְּדַר ָּבה), Why not? Rabba says: We are concerned that perhaps one will blood overrides the rabbinic prohibition against moving ָהא ֲﬠִד ָ יפא, ְּדִאי ָלא ָׁשֵרית ֵל ּיה ָאֵתי .(reconsider and not slaughter it at all, and he will have dug a hole on muktze objects (Shitta Mekubbetzet ְלִאְמ ּ נוֵﬠי ִּׂ ִמשְמַחת יוֹם טוֹב. וְ הוּא – a Festival unnecessarily. And according to my opinion, on the con- And that is when one has a shovel embedded The mishna alludes to this halakha, as it : ֶׁשֵיּׁש לוֹ ֶּדֶקר נָעוּץ -trary: Th is situation, in which he is permitt ed to dig fi rst, is prefer able, since if you do not permit him to dig in all cases for the pur- does not simply state: He digs and covers the blood, but pose of slaughter, he will be unable to eat meat and will refrain from rather: He digs with a shovel, which indicates that there is a shovel ready for this purpose (Ĥatam Sofer, 2nd ed.). -

Moshe Raphael Ben Yehoshua (Morris Stadtmauer) O”H Tzvi Gershon Ben Yoel (Harvey Felsen) O”H

6 Tishrei 5781 Eiruvin Daf 46 Sept. 24, 2020 Daf Notes is currently being dedicated to the neshamot of Moshe Raphael ben Yehoshua (Morris Stadtmauer) o”h Tzvi Gershon ben Yoel (Harvey Felsen) o”h May the studying of the Daf Notes be a zechus for their neshamot and may their souls find peace in Gan Eden and be bound up in the Bond of life Abaye sat at his studies and discoursed on this subject the ocean? — Rabbi Yitzchak replied: Here we are dealing when Rav Safra said to him: Is it not possible that we are with a case where the clouds were formed on the eve of dealing here with a case where the rain fell near a town the festival. But is it not possible that those moved away and the townspeople relied on that rain? — This, the other and these are others? — It is a case where one can replied, cannot be entertained at all. For we learned: A recognize them by some identification mark. And if you cistern belonging to an individual person is on a par with prefer I might reply: This is a matter of doubt in respect of that individual's feet, and one belonging to a town is on a a Rabbinical law and in any such doubt a lenient ruling is par with the feet of the people of that town, and one used adopted. But why shouldn’t the water acquire its place for by the Babylonian pilgrims is on a par with the feet of any the Shabbos in the clouds? May it then be derived from man who draws the water. -

Parshat Tzav & Shabbat Hagadol

Sermon: Parshat Tzav & Shabbat HaGadol ערב פסח תשפ"א / March 27, 2021 Rabbi Mitchell Berkowitz B’nai Israel Congregation Rabba and Rabbi Zeira wanted to get together for a celebratory Purim feast. Following the talmudic dictum of ad d’lo yada, drinking until one cannot distinguish between Blessed Mordecai and Cursed Haman, Rabba and Rabbi Zeira drank too much. In their drunken stupor, Rabba killed Rabbi Zeira. Waking up the next day and realizing this grave mistake, Rabba prayed to God, and Rabbi Zeira was miraculously revived.1 It was a Purim miracle! Why am I telling a story about Purim on this eve of Passover? Two reasons. First of all, the events of the Purim story actually take place during the Pesach season. We celebrate Purim on the 14th of Adar, the date when the Jews of Persia were to be slaughtered, but instead were saved. But the narrative itself takes place during Nisan, even during Passover. Beyond the calendrical association, there is also the theme of miracles. Many of our holidays encompass the celebration of miraculous events: the oil on Hannukah, the saving of the Persian Jews on Purim, the plagues and the splitting of the Sea of Reeds on Passover. Miraculous events remind us that God’s metaphorical hand is at work in this world, and thereby stir within us a deeper sense of trust and faith in God. Let us turn to a different Passover miracle. According to Rabbi Ya’akov ben Asher, the author of the Arba’ah Turim, a great miracle happened for our ancestors in ancient Egypt shortly before the exodus.2 In the Torah, the Israelites were instructed to take a goat into their homes on the 10th day of Nisan, which coincided with Shabbat that year. -

Key Findings from Survey and Community Input Meetings

Three Keys to Unlocking Talmudic Mysteries: Philosophy, Science, and Baseball Trivia June 20, 2021 July 11, 2021 July 18, 2021 Maybe more 1 Overview of June 20 class Review Onward! 2 Two models of philosophy • There is only one right answer. The rest are wrong. • Arguments prove one side is right or the other is wrong. Proof • The goal: discover the right answer. • Usually, there are many acceptable answers. Some may be better than others. • Explanation shows how an answer could be true, despite Explanation a point that initially appears to conflict with the answer. • The goal: understand the full set of acceptable answers. This includes knowing each answer’s strongest possible form and its strengths and weaknesses. 3 Three keys Key #1: 20th- Key #2: Key #3: Century Empirical Baseball philosophy science Trivia All questions are Explain how View P can interesting, and relevance be true in view of X Insiders speak tersely. is irrelevant They understand each other without spelling everything out. Flesh out the best Theories must be adjusted possible version of View P, to fit the data, which identifying its strengths include Biblical and and weaknesses rabbinic statements Outsiders often can’t Do the same with Views make sense of insiders’ Experiments (including Q, R, S, etc., to terse speech. A lot of thought experiments) are understand the set of explanation is required. always specific and often minimally acceptable weird 4 views Rabbeinu Hannanel often on the margins5 6 7 Over there in tractate Eruvin, the Mishna says, “When an alley has a beam that is more than 20 cubits high, it is lowered. -

A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story

A WHITEHEADIAN INTERPRETATION OF THE ZOHARIC CREATION STORY by Michael Gold A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Michael Gold ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to his committee members, Professors Marina Banchetti, Frederick E. Greenspahn, Kristen Lindbeck, and Eitan Fishbane for their encouragement and support throughout this project. iv ABSTRACT Author: Michael Gold Title: A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story Institution: Florida Atlantic University Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Marina P. Banchetti Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Year: 2016 This dissertation presents a Whiteheadian interpretation of the notions of mind, immanence and process as they are addressed in the Zohar. According to many scholars, this kabbalistic creation story as portrayed in the Zohar is a reaction to the earlier rabbinic concept of God qua creator, which emphasized divine transcendence over divine immanence. The medieval Jewish philosophers, particularly Maimonides influenced by Aristotle, placed particular emphasis on divine transcendence, seeing a radical separation between Creator and creation. With this in mind, these scholars claim that one of the goals of the Zohar’s creation story was to emphasize God’s immanence within creation. Similar to the Zohar, the process metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead and his followers was reacting to the substance metaphysics that had dominated Western philosophy as far back as ancient Greek thought. Whitehead adopts a very similar narrative to that of the Zohar. -

Triage: Setting Tzedakah Priorities in a World of Scarcity

Triage: Setting Tzedakah Priorities in a World of Scarcity Noam Zion Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, Israel The Principle of Scarcity versus Faith in God Gender Discrimination: Comparative Shame and Relative Vulnerability Lfi kevdo – “According to one's Individualized Social Status or Honor” – excerpted from: Jewish Giving in Comparative Perspectives: History and Story, Law and Theology, Anthropology and Psychology Book Two: To Each according to one’s Social Needs: The Dignity of the Needy from Talmudic Tzedakah to Human Rights Previous Books: A DIFFERENT NIGHT: The Family Participation Haggadah By Noam Zion and David Dishon LEADER'S GUIDE to "A DIFFERENT NIGHT" By Noam Zion and David Dishon A DIFFERENT LIGHT: Hanukkah Seder and Anthology including Profiles in Contemporary Jewish Courage By Noam Zion A Day Apart: Shabbat at Home By Noam Zion and Shawn Fields-Meyer A Night to Remember: Haggadah of Contemporary Voices Mishael and Noam Zion [email protected] www.haggadahsrus.com 1 Triage: Setting Priorities (TB Ketubot 67a-b) Definition: tri·age Etymology: French, sorting, sifting, from trier to sort, from Old French — 1 a: the sorting of and allocation of treatment to patients and especially battle and disaster victims according to a system of priorities designed to maximize the number of survivors 1b: the sorting of patients (as in an emergency room) according to the urgency of their need for care 2: the assigning of priority order to projects on the basis of where funds and other resources can be best used, are most needed, or are most likely to achieve success. IF AN ORPHAN IS GIVEN IN MARRIAGE SHE MUST BE GIVEN NOT LESS THAN FIFTY ZUZ. -

Shabbat Volume 1.Indb

Perek III Daf 36 Amud b NOTES With regard to a stove that was litN on Shabbat eve A stove that was lit – : The early מתניפ ִ ּ כי ָ אה שׁ ֶ ִ ה ִּ ס י ּ ו ָה ַ ּ ב ַ ּ שׁ ִ ּכי ָ אה שׁ ֶ הִ סִּ י ּ ו הָ with straw or with rakings, scraps collected from -Mishna commentaries explained this issue in differ וּבַ ּג אְבָבָ – נֹותְנִים עָלֶ יהָ ּתַבְשׁ ִ ילד בַּ ֶּג ֶ ׳ת the field, one mayplace a pot of cooked food atop it on Shabbat. The fire ent ways. Many of the ge’onim and those who וּבָעֵצִ ים – לֹא ּןֵ יִת דעַ ֶ שׁ ּיִגְ אֹוב, אֹו דעַ ֶ שׁ ּיִ ֵּ תן in this stove was certainly extinguished while it was still day, as both straw adopted their approach state that this mishna : and rakings are materials that burn quickly. However, if the stove was lit and those that follow are not discussing the אֶ ת הָאֵ ֶ׳אד בֵּ ית שׁ ַ ַּ מאי אֹומְ ִ אים, חַ ִּ מין לו .with pomace, pulp that remains from sesame seeds, olives, and the like question of inserting the pot into the stove אֲבָל לֹא ּתַבְשִׁיל וּבֵית הִ ֵלּל אֹומְ ִ אים, after the oil is squeezed from them, and if it was lit with wood,H one may Rather, they are discussing a case where the חַ ִּ מין וְתַבְשׁ ִ ילד בֵּ ית שׁ ַ ַ ּמאי אֹומְ ִ אים, not place a pot atop it on Shabbat until he sweepsN the coals from the pot is suspended over the stove. -

OF 17Th 2004 Gender Relationships in Marriage and Out.Pdf (1.542Mb)

Gender Relationships In Marriage and Out Edited by Rivkah Blau Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor THE MICHAEL SCHARF PUBLICATION TRUST of the YESHIVA UNIVERSITY PRESs New York OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancediii iii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM THE ORTHODOX FORUM The Orthodox Forum, initially convened by Dr. Norman Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University, meets each year to consider major issues of concern to the Jewish community. Forum participants from throughout the world, including academicians in both Jewish and secular fields, rabbis,rashei yeshivah, Jewish educators, and Jewish communal professionals, gather in conference as a think tank to discuss and critique each other’s original papers, examining different aspects of a central theme. The purpose of the Forum is to create and disseminate a new and vibrant Torah literature addressing the critical issues facing Jewry today. The Orthodox Forum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Joseph J. and Bertha K. Green Memorial Fund at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary established by Morris L. Green, of blessed memory. The Orthodox Forum Series is a project of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancedii ii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orthodox Forum (17th : 2004 : New York, NY) Gender relationships in marriage and out / edited by Rivkah Blau. p. cm. – (Orthodox Forum series) ISBN 978-0-88125-971-1 1. Marriage. 2. Marriage – Religious aspects – Judaism. 3. Marriage (Jewish law) 4. Man-woman relationships – Religious aspects – Judaism. I.