Daf Ditty Pesachim 13: Elijah Not Welcome Erev Shabbes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Bakeries Which Are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? a Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER

Should Bakeries Which are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? A Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER This paper was submitted as a response to the responsum written by Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz and Ms. Dvora Weisberg entitled "Rabbinic Supervision of Jewish Owned Businesses Operating on Shabbat" which was adopted by the CJLS on February 26, 1986. Should rabbis offer rabbinic supervision to bakeries which are open on Shabbat? i1 ~, '(l) l'\ (1) The food itself is indeed kosher after Shabbat, once the time required to prepare it has elapsed. 1 The halakhah is according to Rabbi Yehudah and not according to the Mishnah which is Rabbi Meir's opinion. (2) While a Jew who does not observe all the mitzvot is in some instances deemed trustworthy, this is never the case regarding someone who flagrantly disregards the laws of Shabbat, especially for personal profit. Maimonides specifically excludes such a person's trustworthiness regarding his own actions.2 Moreover in the case of n:nv 77n~ (a violator of Shabbat) Maimonides explicitly rejects his trustworthiness. 3 No support can be brought from Moshe Feinstein who concludes, "even if the proprietor closes his store on Shabbat, [since it is known to all that he does not observe Shabbat], we assume he only wants to impress other observant Jews so they will buy from him."4 Previously in the same responsum R. Feinstein emphasizes that even if the person in The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S

February 5 — 11, 2021 23 — 29 Shevat 5781 Congregation Torah Ohr 19146 Lyons Road, Boca Raton, FL 33434 (561) 479-4049 ● www.torahohrboca.org ● [email protected] Rabbi Benjamin S. Yasgur President, Jonas Waizer Office Hours Monday - Thursday 9:00am - 3:00pm, Friday 9:00am - 12noon WEEKDAY TIMES Earliest Davening (Fri-Thurs) 5:53am* Mishna Yomit (in Shul & online) 15 min. before Mincha Earliest Tallit/Tefillin (Fri-Thurs) 6:20am* Mincha/Ma’ariv (Shul & Tent) (S-Th) Shacharit at Shul (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 7:30am Shacharit in the Tent (starting with Pesukai D’Zimra) 8:30am Daven Mincha (S-Th) prior to 6:08pm Daf Yomi (online) 8:30am Repeat Kriat Shema after 6:46pm* Chumash Class (online) 9:30am *These are the latest times during the week BS”D CONGREGATION TORAH OHR NEW - UPDATED POLICIES FOR KEEPING OUR COMMUNITY SAFE We enjoy the seasonal return of our cherished congregants, friends, and neighbors. At the same time, let us acknowledge that the Corona-19 pandemic is not yet over. We cannot afford complacency in our sheltered senior community until the pandemic is fully controlled. Considering the situation of pikuach nefesh, the Shul will continue policies that protect all our members. We want you in Shul ASAP. But first, individuals returning to Florida, even from short out-of-state stays, must adhere to the CDC, Florida State and Shul rules: a) Self-isolate for 12 days; DO NOT ATTEND SHUL, including outdoor minyanim. If you have no symptoms after 12 days, please SHABBAT YITRO register to attend shul minyanim. -

Shabbat Shalom

" SHABBAT SHALOM. Today is 9 Sivan 5777. We say relationship of a person who sins that the road of sin Kiddush Levanah tonight. multiplies and breeds more sins. In essence the Torah is teaching us the necessity to structure our lives properly in Mazel Tov to Avichai Shekhter upon today’s all dimensions in order to purify our life and the lives of celebration of his Bar Mitzvah. Mazel Tov to Avichai’s those around us. parents Ilya & Hanna Shekhter, and to the entire 3. The emotional response of the husband is described family. as Kin’ah, which we normally translate as jealousy. The negative tension that exists between the husband and wife TORAH DIALOGUE can only come to a bad result. The halachah is that the (p. 586 Hz) (p. 814 S) (p. 527 Hi) (p. 748 AS) entire process of the investigation, denial, and the drinking NASO of the special, potentially lethal waters, cannot begin unless Numbers 4:21 the husband warns his wife and expresses to her his [Compiled by Rabbi Edward Davis (RED) suspicions. This must be done in front of two witnesses. Young Israel of Hollywood-Ft. Lauderdale] Rashi on the Torah and the Rambam (Sotah 1:1) say that the Kin’ah that the Torah refers to is …. that he will say to 1. After completing the description of each of the jobs her in front of witnesses: “Do not be in a secluded place required of the Levitical families, the Torah goes on to with Ploni (a specific-named person)”. The process begins describe what is necessary to purify the Camp of Israel. -

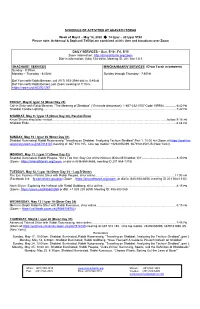

Schedule of Activities at Ahavath Torah

SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES AT AHAVATH TORAH Week of May 8 – May 14, 2020 14 Iyyar – 20 Iyyar 5780 Please note: Ashkenazi & Sephardi Tefillot are combined at this time and broadcast over Zoom DAILY SERVICES – Sun, 5/10 - Fri, 5/15 Zoom Information: http://ahavathtorah.org/zoom Dial-in information: (646) 558-8656, Meeting ID: 201 568 1315 SHACHARIT SERVICES MINCHA/MAARIV SERVICES (D’var Torah in between) Sunday - 9:00AM Monday – Thursday - 8:00AM Sunday through Thursday - 7:50PM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Berman, call (917) 553-3988 dial in, 5:45AM Daf Yomi with Rabbi Becker, join Zoom meeting at 7:10AM https://zoom.us/j/802921287 FRIDAY, May 8/ Iyyar 14 (Omer Day 29) Call-in Shiur with Rabbi Berman, “The Meaning of Shabbos” (10 minute discussion), 1-857-232-0157 Code 159954 .............. 6:42 PM Shabbat Candle Lighting ............................................................................................................................................................. 7:42 PM SHABBAT, May 9 / Iyyar 15 (Omer Day 30), Parshat Emor Kriyat Shema should be recited ....................................................................................................................................... before 9:18 AM Shabbat Ends ............................................................................................................................................................................. 8:48 PM SUNDAY, May 10 / Iyyar 16 (Omer Day 31) Shabbat Illuminated: Rabbi Rosensweig “Traveling on Shabbat: Analyzing Techum Shabbat” Part 1. 10:00 AM -

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

Modern Approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London

09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the View Online Talmud: Sacha Stern Albeck, Chanoch, Mavo La-Talmudim (Tel-Aviv: Devir, 1969) Alexander, Elizabeth Shanks, Transmitting Mishnah: The Shaping Influence of Oral Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) Amit, Aaron, Makom She-Nahagu: Pesahim Perek 4 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2009), Talmud ha-igud Ba’adani, Netanel, Hayu Bodkin: Sanhedrin Perek 5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2012), Talmud ha-igud Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal, Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013) Benovitz, Moshe, Lulav va-Aravah ve-Hahalil: Sukkah Perek 4-5 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2013), Talmud ha-igud ———, Me-Ematai Korin et Shema: Berakhot Perek 1 (Yerushalayim: ha-Igud le-farshanut ha-Talmud, 2006), Talmud ha-igud Brody, Robert, Mishnah and Tosefta Studies, First edition, July 2014 (Jerusalem: The Hebrew university, Magnes press, 2014) ———, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture, Paperback ed., with a new preface and an updated bibliography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013) Carmy, Shalom, Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations (Northvale, N.J.: J. Aronson, 1996), The Orthodox Forum series Chernick, Michael L., Essential Papers on the Talmud (New York: New York University Press, 1994), Essential papers on Jewish studies Daṿid Halivni, Meḳorot U-Masorot (Nashim), ha-Mahadurah ha-sheniyah (Ṭoronṭo, Ḳanadah: Hotsaʼat Otsarenu) ———, Meḳorot U-Masorot: Seder Moʼed (Yerushalayim: Bet ha-Midrash le-Rabanim be-Ameriḳah be-siṿuʻa Keren Moshe (Gusṭaṿ) Ṿortsṿayler, 735) ‘dTorah.com’ <http://dtorah.com/> 1/5 09/29/21 HEBR7411: Modern approaches to the Talmud: Sacha Stern | University College London Epstein, J. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Zeraim Tractates Terumot and Ma'serot

THE JERUSALEM TALMUD FIRST ORDER: ZERAIM TRACTATES TERUMOT AND MA'SEROT w DE G STUDIA JUDAICA FORSCHUNGEN ZUR WISSENSCHAFT DES JUDENTUMS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON E. L. EHRLICH BAND XXI WALTER DE GRUYTER · BERLIN · NEW YORK 2002 THE JERUSALEM TALMUD Ή^ίτ τΐίΛη FIRST ORDER: ZERAIM Π',ΙΓΙΪ Π0 TRACTATES TERUMOT AND MA'SEROT ΓτηελΡΏΐ niQnn rnooü EDITION, TRANSLATION, AND COMMENTARY BY HEINRICH W. GUGGENHEIMER WALTER DE GRUYTER · BERLIN · NEW YORK 2002 Die freie Verfügbarkeit der E-Book-Ausgabe dieser Publikation wurde ermöglicht durch den Fachinformationsdienst Jüdische Studien an der Universitätsbibliothek J. C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main und 18 wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken, die die Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien unterstützen. ISBN 978-3-11-017436-6 ISBN Paperback 978-3-11-068128-4 ISBN 978-3-11-067718-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-090846-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067726-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067730-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. For This work is licensed under the Creativedetails go Commons to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution 4.0 International Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Das E-Book ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com, Library of Congresshttps://www.doabooks.org Control Number: 2020942816und https://www.oapen.org 2020909307 Bibliographic informationLibrary published of Congress by the Control Deutsche Number: Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek DeutscheThe Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data detailedare available bibliographic on the data Internet are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

The Laws of Shabbat

Shabbat: The Jewish Day of Rest, Rules & Cholent Meaningful Jewish Living January 9, 2020 Rabbi Elie Weinstock I) The beauty of Shabbat & its essential function 1. Ramban (Nachmanides) – Shemot 20:8 It is a mitzvah to constantly remember Shabbat each and every day so that we do not forget it nor mix it up with any other day. Through its remembrance we shall always be conscious of the act of Creation, at all times, and acknowledge that the world has a Creator . This is a central foundation in belief in God. 2. The Shabbat, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, NCSY, NY, 1974, p. 12 a – (אומן) It comes from the same root as uman .(אמונה) The Hebrew word for faith is emunah craftsman. Faith cannot be separated from action. But, by what act in particular do we demonstrate our belief in God as Creator? The one ritual act that does this is the observance of the Shabbat. II) Zachor v’shamor – Remember and Safeguard – Two sides of the same coin שמות כ:ח - זָכֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Exodus 20:8 Remember the day of Shabbat to make it holy. Deuteronomy 5:12 דברים ה:יב - ׁשָמֹוראֶ ת יֹום הַשַבָתלְקַדְ ׁשֹו... Safeguard the day of Shabbat to make it holy. III) The Soul of the Day 1. Talmud Beitzah 16a Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said, “The Holy One, Blessed be He, gave man an additional soul on the eve of Shabbat, and at the end of Shabbat He takes it back.” 2 Rashi “An additional soul” – a greater ability for rest and joy, and the added capacity to eat and drink more. -

Nazir" Legislation

266 JOURNA.i.. OP BIBLICAL ·LITERATURE The "Nazir" Legislation. MORRIS JASTROW, JR. UNIVBBSlTY Oll' PDNSYLV.ANU. I. TN a paper which I read before the Society at its meeting ~last year, on Leviticus, Chapters 13-14,1 the so-called "Le prosy" Laws, I endeavored to show that in these two cbapten we may detect the same process of steady amplification of an original stock of regulations by means of comments and glosses and illustrative instances which we may observe in the great compilation of Rabbinical Judaism known as the Talmud, where a condensed and a comparatively simple Mishna develops into an elaborate and intricate Gemara. The importance of the thesis-if correct-lies in the possibility thns afforded ofseparat ing between older and later layers in the regulations of the Pentateuchal Codes, but more particularly in furnishing the proof that these codes in which old and new have been com bined-precisely as in the narrative sections of the Pentateuch and in the historical books proper, older and later documents (with all manner of additions) have been dovetailed into one another-reflect an extended and uninterrupted process of growth, covering a long period of time and keeping pace with the tendency to adapt older regulations to later conditions. It is my intention to test the thesis by its application to other little groups of laws within the Codes, recognized by scholan as representing distinct units, and I choose as an example for presentation at this meeting Numbers 61-21, containing the laws of the so-called "Nazir". 1 Published in the Jewilh Quarter~y Review, New Series, IV, 357-418. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement.