Ask the Rabbi Volume Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters Micah Holt University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Holt, Micah, "Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2682. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112082 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPLIED ANATOMY IN MUSIC: BODY MAPPING FOR TRUMPETERS By Micah N. Holt Bachelor of Arts--Music University of Northern Colorado 2010 Master of Music University of Louisville 2012 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2016 Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas April 24, 2016 This dissertation prepared by Micah N. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

Seudas Bris Milah

Volume 12 Issue 2 TOPIC Seudas Bris Milah SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Proofreading: Mrs. EM Sonenblick monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, Website Management and Emails: a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva Heshy Blaustein Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Dedicated in honor of the first yartzeit of Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles SPONSORED: discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of לרפואה שלמה ,all relevant shittos on each topic חיים צבי בן אסתר as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current SPONSORED: issues. לעילוי נשמת WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה Halachically Speaking is בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט .distributed to many shuls גערשטנער It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far SPONSORED: Rockaway, and Queens, The ,Flatbush Jewish Journal לרפואה שלמה להרה"ג baltimorejewishlife.com, The רב חיים ישראל בן חנה צירל Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2015 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking ח.( )ברכות Seudas Bris Milah בלבד.. -

2302.Jerome Dretzka Papers

Title: Dretzka, Jerome Papers Reference Code: Mss-2302 Inclusive Dates: 1909-1963 Quantity: 10 cu. ft. Location: NE, Sh. 048-051 OS LG “D” Abstract: Jerome C Dretzka (1881-1963) served on the Milwaukee County Parks Commission from 1920-1963. During that tenure, from 1926-1952, he served as the Executive Secretary of the Commission and expanded the area of Milwaukee parks considerably. He also served as an officer for the American Institute of Park Executives. He retired in 1952. He was born on December 5, 1881 in Pozen, Poland. His family moved to America when he was five years old and they settled on the south side of Milwaukee. In 1893, his family moved to Cudahy where he continued to reside until his death. He served as the city of Cudahy’s city clerk from 1912-1916. He left this position to manage the real estate holdings of Patrick Cudahy. This knowledge served him well during his time on the Commission and during his tenure the Commission went from owning 680 acres to over 7,000 acres of parks. He also served on the boards of the Milwaukee County Historical Society, New Zoo Conference Committee, Wisconsin Park and Recreation Society, as well as many others. Scope and Content: The bulk of the collection consists of material pertaining to Milwaukee County Park Commission and some of the material pertains to his participation in the American Institute of Park Executives (AIPE).In the form of correspondence, newspaper clippings, meeting minutes and official papers from the Commission. This collection also includes information about various projects that he was involved with including the zoo, Mitchell Conservatory, the Braves, and the Milwaukee County Stadium. -

A Taste of Jewish Law & the Laws of Blessings on Food

A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food (2003 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10018985 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A ‘‘TASTE’’ OF JEWISH LAW -- THE LAWS OF BLESSINGS ON FOOD Jeremy Hershman Class of 2003 April 2003 Combined Course and Third Year Paper Abstract This paper is an in-depth treatment of the Jewish laws pertaining to blessings recited both before and after eating food. The rationale for the laws is discussed, and all the major topics relating to these blessings are covered. The issues addressed include the categorization of foods for the purpose of determining the proper blessing, the proper sequence of blessing recital, how long a blessing remains effective, and how to rectify mistakes in the observance of these laws. 1 Table of Contents I. Blessings -- Converting the Mundane into the Spiritual.... 5 II. Determining the Proper Blessing to Recite.......... 8 A. Introduction B. Bread vs. Other Grain Products 1. Introduction 2. Definition of Bread – Three Requirements a. Items Which Fail to Fulfill Third Requirement i. When Can These Items Achieve Bread Status? ii. Complications b. -

Yeshiva University • Shavuot To-Go • Sivan 5768

1 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY • SHAVUOT TO-GO • SIVAN 5768 Dear Friends, may serve to enhance your ספר It is my sincere hope that the Torah found in this virtual .(study) לימוד holiday) and your) יום טוב We have designed this project not only for the individual, studying alone, but perhaps even a pair studying together) that wish to work through the study matter) חברותא more for a together, or a group engaged in facilitated study. להגדיל תורה ,With this material, we invite you to join our Beit Midrash, wherever you may be to enjoy the splendor of Torah) and to engage in discussing Torah issues that) ולהאדירה touches on a most contemporary matter, and which is rooted in the timeless arguments of our great sages from throughout the generations. בברכת חג שמח Rabbi Kenneth Brander Richard M Joel, President, Yeshiva University Rabbi Kenneth Brander, Dean, Center for the Jewish Future Rabbi Robert Shur, General Editor Ephraim Meth, Editor Aaron Steinberg, Family Programming Editor Copyright © 2008 All rights reserved by Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future 500 West 185th Street, Suite 413, New York, NY 10033 [email protected] • 212.960.0041 2 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY • SHAVUOT TO-GO • SIVAN 5768 Table of Contents Shavuot 2008/5768 Learning Packets Halachic Perspectives on Live Kidney Donations Rabbi Josh Flug “Can I Have a Ride?” Carpooling & Middas Sodom Rabbi Daniel Stein Divrei Drush The Significance of Matan Torah Dr. Naomi Grunhaus Shavuot: Middot and Torah Linked Together Rabbi Zev Reichman Twice Kissed Rabbi Moshe Taragin Family Program Pirkei Avot Scavenger Hunt Environmentalism in Jewish Law and Thought The Jew's Role in the World Aaron Steinberg 3 YESHIVA UNIVERSITY • SHAVUOT TO-GO • SIVAN 5768 Dear Readers, Torah was neither received nor fulfilled in a vacuum. -

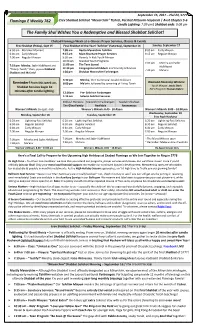

The Family Shul Wishes You a Redemptive and Blessed Shabbat Selichot!

September 15, 2017 – Elul 24, 5777 Flamingo E Weekly 762 Erev Shabbat Selichot “Mevarchim” Tishrei, Parshat Nitzavim-Vayelech | Avot Chapter 5-6 Candle Lighting: 7:09 pm| Shabbat ends: 8:08 pm The Family Shul Wishes You a Redemptive and Blessed Shabbat Selichot! Chabad Flamingo Week-at-a-Glance: Prayer Services, Classes & Events Erev Shabbat (Friday), Sept 15 Final Shabbat-of-the-Year! “Selichot” (Saturday), September 16 Sunday, September 17 6:30 am Ma’amer Moment 7:00 am Recite Mevarchim Tehillim 8:00 am Early Minyan 6:40 am Early Minyan 9:15 am Main Shacharit Prayer Services 9:15 am Regular Minyan 7:00 am Regular Minyan 9:30 am Parents ’n Kids Youth Minyan 10:30 am Shabbat Youth Programs 7:00 pm Mincha and Sefer 11:00 am The Teen Scene! 7:19 pm Mincha, Sefer HaMitzvot and HaMitzvot 12:30 pm Congregational Kiddush and Friendly Schmooze “Timely Torah;” then, joyous Kabbalat 7:30 pm Ma’ariv 1:30 pm Shabbat Mevarchim Farbrengen Shabbat and Ma’ariv! 6:30 pm Mincha, then Communal Seudah Shlisheet Reminder! From this week on, 8:00 pm Ma’ariv, followed by screening of Living Torah Diamond Davening Winners: Shabbat Services begin 10 Youth Minyan: Jacob Stark Kid’s Program: Hudson Kobric minutes after candle lighting. 12:00am Pre- Selicho t Farbrengen 1:15 am Solemn Selichot Services Kiddush Honours: Mevarchim Farbrengen: Seudah Shlisheet The Glina Family Available Anonymous Women’s Mikvah: by appt. only Women’s Mikvah: 8:45 - 10:45pm Women’s Mikvah: 8:00 – 10:00 pm Wednesday, September 20 Monday, September 18 Tuesday, September 19 Erev Rosh -

Reflecting on When the Arukh Hashulhan on Orach Chaim Was Actually Written,There Is No Bracha on an Eclipse,A Note Regarding

Reflecting on When the Arukh haShulhan on Orach Chaim was Actually Written Reflecting on When the Arukh haShulhan on Orach Chaim was Actually Written: Citations of the Mishnah Berurah in the Arukh haShulhan Michael J. Broyde & Shlomo C. Pill Rabbi Michael Broyde is a Professor of Law at Emory University School of Law and the Projects Director at the Emory University Center for the Study of Law and Religion. Rabbi Dr. Shlomo Pill is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Jewish, Islamic, and American Law and Religion at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology and a Senior Fellow at the Emory University Center for the Study of Law and Religion. They are writing a work titled “Setting the Table: An Introduction to the Jurisprudence of Rabbi Yechiel Mikhel Epstein’s Arukh Hashulchan” (Academic Studies Press, forthcoming 2020). We post this now to note our celebration of the publication of תערוך לפני שלחן: חייו, זמנו ומפעלו של הרי”מ עפשטיין בעל ערוך Set a Table Before Me:The Life, Time, and Work of“) השלחן Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Epstein, Author of the Arukh HaShulchan” .הי”ד ,see here) (Maggid Press, 2019), by Rabbi Eitam Henkin) Like many others, we were deeply saddened by his and his wife Naamah’s murder on October 1, 2015. We draw some small comfort in seeing that the fruits of his labors still are appearing. in his recently published הי”ד According to Rabbi Eitam Henkin book on the life and works of Rabbi Yechiel Mikhel Epstein, the first volume of the Arukh Hashulchan on Orach Chaim covering chapters 1-241 was published in 1903; the second volume addressing chapters 242-428 was published in 1907; and the third volume covering chapters 429-697 was published right after Rabbi Epstein’s death in 1909.[1] Others confirm these publication dates.[2] The Mishnah Berurah, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan’s commentary on the Orach Chaim section of the Shulchan Arukh was published in six parts, with each appearing at different times over twenty- three-year period. -

Vayigash 5776

Vayigash Vayigash, 7 Tevet 5776 “Sending Everyone Out” Harav Yosef Carmel Before Yosef revealed his identity to his brothers, he commanded the members of his court: “Send everyone out from before me” (Bereishit 45:1). We will try to explain why it was so important to Yosef to be alone with his brothers. The midrash (Sechel Tov, Bereishit 45) explains that this was done for the needs of modesty. As Yosef was going to prove his identity by showing he was circumcised, he did not want his assistants to see what was not necessary for them to see. The simple explanation, of course, is that Yosef wanted to protect his brothers from embarrassment at the awkward situation that was to occur, which would include no small amount of explicit or implicit rebuke. Rishonim put stress on the rebuke, including practical ramifications, stemming from it, other than the brothers’ simple embarrassment. The Ramban says that upon hearing of Yosef’s sale, the Egyptians would view the brothers as betrayers and would reason that if that is the way they treated their own brother, they certainly could not be trusted to live in Egypt and visit in its palace. The Da’at Zekeinim echoes this idea but also extends it, in showing how the matter of the sale was a bigger secret than we might assume. They claim that not only did Yaakov not know about the sale, but even Binyamin, who was not with his brothers at the time, did not know about it. In fact, they claim that Yosef broke his speech of revelation into two. -

Potential Risk and Protective Factors for Eating Disorders in Haredi (Ultra‑Orthodox) Jewish Women

Journal of Religion and Health (2019) 58:2161–2174 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00854-2 PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLORATION Potential Risk and Protective Factors for Eating Disorders in Haredi (ultra‑Orthodox) Jewish Women Rachel Bachner‑Melman1,2 · Ada H. Zohar1 Published online: 7 June 2019 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Little is known scientifcally about eating disorders (EDs) in the Haredi (Jewish ultra-Orthodox) community. This paper aims to describe Haredi culture, review available peer-reviewed research on EDs in the Haredi community and discuss pos- sible risk and protective factors for these disorders in a culturally informed way. A literature search for 2009–2019 yielded 180 references of which only nine were stud- ies on ED in the Haredi community. We describe these and use them as a basis for discussion of possible risk and protective factors for ED in Haredi women. Risk fac- tors may include the centrality of food, poverty, rigid dress codes, the importance of thinness for dating and marriage, high demands from women, selfessness and early marriage and high expectations from women. Protective factors may include faith, Jewish laws governing eating and food that encourage gratitude and mindful eat- ing, and body covering as part of modesty laws that discourage objectifcation. Ways of overcoming the current barriers to research in the Haredi community should be sought to advance ED prevention and treatment in this population. Keywords Eating disorders · ultra-Orthodox · Haredi · Risk and protective factors · Body image Introduction Eating disorders (EDs) are characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating-related behavior that leads to altered consumption of food and the impairment of physical health or psychosocial functioning (APA 2013). -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Acharei Mot Vol.26 No.29:Layout 1

s; vacug s; tjrh nu, tjrh Volume 26 ACHAREI MOT No. 29 SHABBAT HAGADOL Daf Hashavua 12 April 2014 • 12 Nisan 5774 Shabbat ends in London at 8.41pm Artscroll p.636 Haftarah p.1220 Pesach begins on Monday night Hertz p.480 Haftarah p.1105 Soncino p.705 Haftarah p.1197 Sayings & Rav Ashi Sayers of the Sidrah by Rabbi Samuel Landau, Kingston, Surbiton & District United Synagogue Chumash: (referring to the High Priest’s cially successful. He was head of the Yom Kippur service): ‘And he shall place the academy in Sura, which flourished under his incense upon the fire before G-d, so that the leadership. cloud of the incense shall cover the ark cover that is over the [tablets of] Testimony, Rav Ashi, partnered by Ravina, had a so that he shall not die’. (Vayikra 16:13) single, great ambition – to record for posterity the discussions across the Talmud: ‘So that the cloud…shall generations that had elucidated cover’. Rav Ashi said: This [pas- the Mishnah, as well sage] tells us that the incense as recording the should be burned. Another [pass- mystical, cultural and age, elsewhere] tells us that if social statements of this is not done, the whole the sages. incense service is void‘. (Yoma 53a) Rav Ashi’s success in this project was due in no In c.500 CE, alongside his colleague small part to the length of time he devoted Ravina, Rav Ashi drew to a close the to it – 60 years! These 60 years were exact- Talmud/Gemara – the body of work that ingly allocated.