Reflecting on When the Arukh Hashulhan on Orach Chaim Was Actually Written,There Is No Bracha on an Eclipse,A Note Regarding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seudas Bris Milah

Volume 12 Issue 2 TOPIC Seudas Bris Milah SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Proofreading: Mrs. EM Sonenblick monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, Website Management and Emails: a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva Heshy Blaustein Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky Shlita. Rabbi Dedicated in honor of the first yartzeit of Lebovits currently works as the Rabbinical Administrator for ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. SPONSORED: Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles SPONSORED: discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of לרפואה שלמה ,all relevant shittos on each topic חיים צבי בן אסתר as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current SPONSORED: issues. לעילוי נשמת WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה Halachically Speaking is בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט .distributed to many shuls גערשטנער It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far SPONSORED: Rockaway, and Queens, The ,Flatbush Jewish Journal לרפואה שלמה להרה"ג baltimorejewishlife.com, The רב חיים ישראל בן חנה צירל Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2015 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking ח.( )ברכות Seudas Bris Milah בלבד.. -

A Taste of Jewish Law & the Laws of Blessings on Food

A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation A Taste of Jewish Law & The Laws of Blessings on Food (2003 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10018985 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A ‘‘TASTE’’ OF JEWISH LAW -- THE LAWS OF BLESSINGS ON FOOD Jeremy Hershman Class of 2003 April 2003 Combined Course and Third Year Paper Abstract This paper is an in-depth treatment of the Jewish laws pertaining to blessings recited both before and after eating food. The rationale for the laws is discussed, and all the major topics relating to these blessings are covered. The issues addressed include the categorization of foods for the purpose of determining the proper blessing, the proper sequence of blessing recital, how long a blessing remains effective, and how to rectify mistakes in the observance of these laws. 1 Table of Contents I. Blessings -- Converting the Mundane into the Spiritual.... 5 II. Determining the Proper Blessing to Recite.......... 8 A. Introduction B. Bread vs. Other Grain Products 1. Introduction 2. Definition of Bread – Three Requirements a. Items Which Fail to Fulfill Third Requirement i. When Can These Items Achieve Bread Status? ii. Complications b. -

The Gender of Shabbat

The Gender of Shabbat Aryeh Cohen Introduction “Women are like men in regards to Shabbat …”1 There are several specific ways in which Shabbat itself, the day, not the tractate, is gendered. Shabbat is called a “bride” (bShab 119a). At the onset of Shabbat, the sunset on Friday evening, the Bavli relates that sages would go out to greet the bride, Shabbat the Queen. Shabbat is “brought in” on command of the man of the house. He interro- gates the woman: “have you tithed?” “Have you made an eruv?” Upon receiving the correct answers he commands: “Light the candles,” (mShab 2:7).2 The Mishnah distinguishes between what a man is allowed to wear out of the house on Shabbat and what a woman is allowed to wear out of the house on Shabbat. The discussions center on jewelry and other “accessories” for a woman and body armor and weapons for a man (mShab 6:1-3). The prohibitions serve to construct the masculine and the feminine.3 However, I want to look elsewhere. mShabbat starts with distinguishing be- tween inside and outside. This should be familiar terrain for feminist theory. However, when we look at mShab 1:1, there is no distinction drawn between a man and a woman. In the complicated choreography of transgression illustrated in this text, it is the house-owning man who inhabits the inside and the poor man who stands outside. יציאות השבת שתים שהן ארבע בפנים, ושתים שהן ארבע בחוץ. כיצד? העני עומד בחוץ ובעל הבית בפנים. פשט העני את ידו לפנים ונתן לתוך ידו של בעל הבית, או שנטל מתוכה והוציא, העני חייב ובעל הבית פטור. -

Shabbat, July 5 Parshat Balak Calling All Teens!

Candles: 6:58-8:13 Havdalah: 9:13 Welcome to the Shabbat Parshat Balak Parsha: p. 856 July 5, 2014 7 Tammuz 5774 Haftarah: p. 1189 .Sun. Mon. Tue. Wed. Thu. Fri שבת .Fri July 4 July 5 July 6 July 7 July 8 July 9 July 10 July 11 Independence Day Shacharit 7:30, 9:00 8:00 6:35 6:45 6:45 6:35 6:45 Latest Shema 9:20 am 8:00 Mincha/Maariv 6:50 8:00/9:12 8:15 8:15 8:15 8:15 8:15 6:45 Earliest Shema 9:20 pm COMMUNITY KIDDUSH sponsored by the Zazulia family in honor of Aaron's birthday on the 4th of July and Corina's birthday on the 16th; and by Phillip, Iris, Rina, Sahpir and Mayahon Freedman in loving memory of Fern Freedman at her Yahrtzeit. SEUDAH SHELISHIT sponsored by the Shul. DAT MINYAN NEWS AND EVENTS Please note that with many people away, LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES several classes are not meeting this Shabbat. DAY TIME TOPIC TEACHER PLACE Please see box at right. Fri. After Mincha D’var Torah Dr. N. Rabinovitch MPR Eruv Notice—Thank You to all those who contributed to the Eruv’s emergency appeal. Not Meeting Tefillah Rabbi Klein N/A Thanks to the community’s support, the Er- 9:45 am Women’s Parsha Chavura 204 uv will not need to be taken down. You can Haft/Mussaf Pirkei Avot Rabbi Gitler 111 still donate anytime by going to the Eruv After Mussaf Derasha Reb Noam Horowitz MPR website, DenverEruv.org. -

Announcements for Parshas Pekudei

Congregation Ahavas Yisrael 1587 Route 27, Edison, NJ 08817 www.AYEDISON.org // Rabbi Gedaliah Jaffe // President David Zelingher // [email protected] This Shabbos: Fri Shabbos Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Parshas Naso May 29 May 30 May 31 June 1 June 2 June 3 June 4 Shacharis 6:15AM 6:45 / 8:45AM 8:15AM 6:10AM 6:15AM 6:15AM 6:10AM Mincha/ Candlelighting 7:00 / 8:01 PM 7:50PM 8:05PM 8:05PM 8:05PM 8:05PM 8:05PM Ma’ariv / Havdalah 9:10PM 8:25PM 8:25PM 8:25PM 8:25PM 8:25PM Next Shabbos: Fri Shabbos Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Parshas Beha'alosecha June 5 June 6 June 7 June 8 June 9 June 10 June 11 Shacharis 6:15AM 6:45 / 8:45 8:15AM 6:10AM 6:15AM 6:15AM 6:10AM Mincha/ Candlelighting 7:00 / 8:06 PM 7:55PM 8:10PM 8:10PM 8:10PM 8:10PM 8:10PM Ma’ariv / Havdalah 9:15PM 8:30PM 8:30PM 8:30PM 8:30PM 8:30PM Weekly Shiurim at AY: Fri Shabbos Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs May 29 May 30 May 31 June 1 June 2 June 3 June 4 Dirshu Daf Yomi B’Halacha 6:00AM 6:00AM 6:00AM 6:00AM 6:00AM Nesivos Shalom Shiur (NEW) 7:05 PM Hilchos Shabbos Chabura 8:25AM Personalities of the Talmud No shiur Bava Kama Chabura 8:45PM SHUL ANNOUNCEMENTS YIZKOR PLEDGES from the second day of Shavuos should be redeemed as soon as possible. Pledges can be paid online via the shul website or by giving a check to Rabbi Jaffe. -

Melilah Agunah Sptib W Heads

Agunah and the Problem of Authority: Directions for Future Research Bernard S. Jackson Agunah Research Unit Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester [email protected] 1.0 History and Authority 1 2.0 Conditions 7 2.1 Conditions in Practice Documents and Halakhic Restrictions 7 2.2 The Palestinian Tradition on Conditions 8 2.3 The French Proposals of 1907 10 2.4 Modern Proposals for Conditions 12 3.0 Coercion 19 3.1 The Mishnah 19 3.2 The Issues 19 3.3 The talmudic sources 21 3.4 The Gaonim 24 3.5 The Rishonim 28 3.6 Conclusions on coercion of the moredet 34 4.0 Annulment 36 4.1 The talmudic cases 36 4.2 Post-talmudic developments 39 4.3 Annulment in takkanot hakahal 41 4.4 Kiddushe Ta’ut 48 4.5 Takkanot in Israel 56 5.0 Conclusions 57 5.1 Consensus 57 5.2 Other issues regarding sources of law 61 5.3 Interaction of Remedies 65 5.4 Towards a Solution 68 Appendix A: Divorce Procedures in Biblical Times 71 Appendix B: Secular Laws Inhibiting Civil Divorce in the Absence of a Get 72 References (Secondary Literature) 73 1.0 History and Authority 1.1 Not infrequently, the problem of agunah1 (I refer throughout to the victim of a recalcitrant, not a 1 The verb from which the noun agunah derives occurs once in the Hebrew Bible, of the situations of Ruth and Orpah. In Ruth 1:12-13, Naomi tells her widowed daughters-in-law to go home. -

Erev Passover on Shabbos

Rabbi Aaron Kraft Dayan EREV PESACH WHICH OCCURS ON SHABBOS: A Practical Guide When Erev Pesach coincides with Shabbos, we benefit from Friday (13th of Nisan; this year, March 26, 2021) or Shabbos having a restful and spiritually uplifting day leading into the (Erev Pesach; this year, March 27, 2021)? The Shulchan Aruch Seder night. However, this infrequent calendrical occurrence (ibid.) says to burn most of the chametz on Friday, leaving some also raises practical questions relating to the halachos of Erev for the Shabbos meals (see next section). Whatever chametz Pesach1 as well as to the proper fulfilment of the mitzvos of remains after the meals should be broken into small crumbs Shabbos. This article will address these concerns. and disposed of in a manner that destroys it completely but does not violate the laws of Shabbos. Preferred methods include flushing the crumbs down the toilet, feeding them to TAANIS BECHOROS a pet, or throwing them into a garbage outside of the house. While on a regular Erev Pesach, firstborn males customarily Larger quantities may also be given to a non-Jew (but you fast, fasting is prohibited on Shabbos either because it detracts should not directly ask the non-Jew to remove more than from the mitzvah of oneg Shabbos or because an obligation to a meal’s worth of chametz from your house – see Shulchan eat three meals exists (OC 288:1 and Beur Halacha). Therefore, Aruch 444:4 and Mishna Berura 444:18-20). the Beis Yosef (OC 470) cites opposing positions whether to According to the Shulchan Aruch (OC 444:2), the burning observe the taanis on Thursday or not at all this year. -

Electricity and Shabbat

5778 - bpipn mdxa` [email protected] 1 c‡qa HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 87 - ELECTRICITY & SHABBAT: PART 1 - GENERAL PRINCIPLES OU ISRAEL CENTER - SPRING 2018 A] HALACHIC ISSUES CONCERNING ELECTRICITY1 (i) Melachot on Shabbat (a) Connecting/breaking an electrical circuit (b) Time switches (c) Use of filament/fluorescent /LED lights; other light generation (e.g. chemical) (d) Electrical heating/cooking - microwaves, solar heaters, central heating (e) Cellphones and computers (f) Hearing aids/microphones (g) Electronic keys - hotels, student accommodation (h) Electronic security equipment - metal detectors, cameras, motion sensors (i) Automatic doors, bells and chimes (j) Shabbat elevators (k) Dishwashers (l) Medical monitoring (m) Radio/screens (n) Watches (ii) Light for Mitzvot (a) Ner Shabbat (b) Ner Havdala (c) Ner Chanukah (d) Bedikat Chametz (iii) Electrical Power (a) Baking matzot (b) Making tzitzit (c) Shaving (d) Filling a mikva (iv) Electronic Media (a) Use of microphones for mitzvot of speech/hearing - berachot, megilla, shofar, kiddushin, kinyanim (b) Erasing Shem Hashem stored or displayed electronically (c) Kol isha through a microphone (d) Accepting witness testimony through telephone/video (e) Bikur cholim/ nichum aveilim on the telephone (f) Issurim via TV/video - e.g. pritzut (v) Kashrut (a) Kashering meat/liver using an electric element (b) Kashering electric appliances (c) Cooking meat and milk using electrically generated heat (d) Tevilat kelim for electrical appliances 1. For further reading see: The Use of Electricity on Shabbat and Yom Tov - R. Michael Broyde and R. Howard Jachter - Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society - Vol. XXI p.4; Encyclopedia Talmudit Vol. 8 155-190 and 641-772; The Blessing of Eliyahu (pub. -

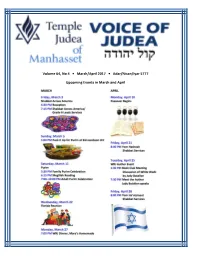

2017 – Mar-Apr

61, No. 1 September/October 2013 Elul 5773/Tishrei/Cheshvan 5774 Volume 64, No 4 • March/April 2017 • Adar/Nisan/Iyar 5777 Upcoming Events in March and April TEMPLE NEWS Temple Judea of Manhasset Schedule of Friday Night Services Affiliated with the Union of Reform Judaism March 3 Shabbat Service: 7:15 PM 333 Searingtown Road | Manhasset, NY 11030 Torah Portion: Terumah 516-621-8049 March 10 www.temple-judea.com Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM Todd Chizner…………………...…...……....Rabbi Torah Portion: Tetzaveh Abbe Sher………...…….…........……….....Cantor March 17 Abner L. Bergman, z”l.....…................Rabbi Emeritus Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM Eugene J. Lipsey, z”l…………................Rabbi Emeritus Torah Portion: Ki Tisa Richard Berman……………….................Cantor Emeritus March 24 Maxine Peresechensky…….................Executive Director Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM Torah Portion: Vayakhel -Pekudei Lauren Resnikoff…………..……….….......Educator Erik Groothuis........…………….……….….President March 31 Shabbat Service: 7:30 PM TEMPLE JUDEA BULLETIN Torah Portion: Vayikra Published Five Times Annually April 7 Sheri ArbitalJacoby ….………………...Editor Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM Torah Portion: Tzav Temple Judea Is Handicapped Accessible April 14 Shabbat Service: 6:30 PM Condolences to Cindy Roberts on the loss of her beloved Torah Portion: Chol Hamoed father, Leon Nass. April 21 Condolences to Phyllis Levine on the loss of her beloved Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM husband, Mel. Torah Portion: Shemini Condolences to Sharon Sharon on the loss of her beloved April 28 father, Theodore Barberer. Shabbat Service: 8:00 PM Condolences to Alyce Tucker on the loss of her beloved Torah Portion: Tazria-Metzora mother, Sheila Kessler. Condolences to Jodi Cohen Graver on the loss of her beloved mother and father, Barbara and Arthur Cohen. -

What Is Bothering the Aruch Hashulchan? Women Wearing Tefillin

What is Bothering the Aruch Hashulchan? Women Wearing Tefillin What is Bothering the Aruch Hashulchan? Women Wearing Tefillin Michael J. Broyde [email protected] Please note that this piece isn’t meant to be construed one way or another as the view of the Seforim Blog. Introduction In our previous article,[1] we focused on the view of the Mishnah Berurah concerning women wearing tefillin. In this article, we focus on the Aruch Hashulchan, whose approach is also complex, reflecting the complexity of the area. The Aruch Hashulchan (OC 38:6) states: נשים ועבדים פטורים מתפילין מפני שהיא מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא דשבת ויו”ט פטור מתפילין ואם רוצין להחמיר על עצמן מוחין בידן ולא דמי לסוכה ולולב שפטורות ועכ”ז מברכות עליהן דכיון דתפילין צריך זהירות יתירה מגוף נקי כדאמרינן בשבת [מ”ט.] תפילין צריכין גוף נקי כאלישע בעל כנפים ובירושלמי ברכות שם אמרו תמן אמרין כל שאינו כאלישע בעל כנפים אל יניח תפילין אך אנשים שמחויבים בהכרח שיזהרו בהם בשעת ק”ש ותפלה ולכן אין מניחין כל היום כמ”ש בסי’ הקודם וא”כ נשים שפטורות למה יכניסו עצמן בחשש גדול כזה ואצלן בשעת ק”ש ותפלה כלאנשים כל היום לפיכך אין מניחין אותן להניח תפילין ואף על גב דתניא בעירובין [צ”ו.] דמיכל בת שאול היתה מנחת תפילין ולא מיחו בה חכמים אין למידין מזה דמסתמא ידעו שהיא צדקת גמורה וידעה להזהר וכן עבדים כה”ג [עמג”א סק”ג וב”י ולפמ”ש א”ש[: Women and slaves are exempt from the mitzvah of tefillin since it is a positive commandment that is time bound since tefillin are not worn on Shabbat and Yom Tov. -

Burdening the Public

Volume 14 Issue 10 TOPIC Burdening the Public SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi MoisheCompiled Dovid by Lebovits Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi WebsiteWebsite Management Management and and Emails: Emails: HALACHICALLY SPEAKING HeshyHeshy Blaustein HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Halachically Speaking is a monthly publication compiled by monthly publication compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, SPONSORED Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva לזכר נשמת מורי ורבי Torah Vodaath and and a a musmach of of Torah Vodaath musmach הרה"ג רב חיים ישראל HaravHarav Yisroel Yisroel Belsky Belsky zt”l Shlita. Rabbi. Rabbi LebovitsLebovits currently currently works works as the as the ב"ר דוב זצ"ל בעלסקי RabbinicalRabbinical Administrator Administrator for for Dedicated in memory of thethe KOF-K KOF-K Kosher Kosher Supervision. Supervision. לז"נ ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה Each Each issue issue reviews reviews a different a different ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה area of contemporary halacha SPONSORED area of contemporary halacha SPONSORED: withwith an anemphasis emphasis on onpractical practical applications of the principles לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה applications of the principles discussed. Significant time is לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה discussed. Significant time is SPONSORED spent ensuring the inclusion of spent ensuring the inclusion of ,all relevant shittos on each topic לעילוי נשמת:SPONSORED as allwell relevant as the shittos psak onof eachHarav topic, as well as the psak of Harav מרת לעילוי בריינדל חנה נשמתע"ה Yisroel Belsky, zt”l on current בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט גערשטנער issues.Yisroel Belsky, Shlita on current מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה .issues בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט גערשטנער WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKINGWHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is distributed Halachically to many Speaking shuls. -

Lechem Mishna on Shabbos

Chayei Sarah 5781/November 13, 2020 Volume 3, Issue 6 Lechem Mishna on Shabbos Rabbi Chaim Yeshaya Freeman How many of the loaves of lechem mishna need to be cut for the Shabbos meal? Which bread must be covered during kiddush? The requirement: The Gemara (Brachos 39b) cites a teaching of Rav Abba loaves if, as pointed out by Rav Kahana as the basis for his opinion, the Torah that on Shabbos, during every meal, a person is required to break bread over states that the Jewish People “gathered” a double portion. lechem mishna, two loaves. This is based upon the verse (Shemos 16:22) that MidiOraysa or midiRabanan: The Taz (Orach Chaim 678:2) says that lechem relates that a double portion of mon (manna) fell on Fridays: “It happened on mishna is a diOraysa (Scriptural) obligation. The Taz is discussing a case of one the sixth day that they gathered a double portion of food.” Hashem explained who has limited finances and must choose between purchasing bread forlechem to Moshe that one portion was meant for Friday, and one for Shabbos, as no mishna or wine for kiddush. He rules that the lechem mishna takes precedence as mon fell on Shabbos itself. Chazal inferred that two loaves of bread should be the requirement of lechem mishna is diOrayso, while the requirement of wine for used to symbolize the double portion that fell in honor of Shabbos. The Gemara kiddush is Rabbinic. However, the Magen Avraham (618:10 and 254:23) argues continues that Rav Ashi said that he witnessed Rav Kahana hold two loaves of that lechem mishna is a diRabanan (Rabbinic) obligation.