Scotland's Global Empire Internals.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded seven times Ralph Bunche, U.S., UN Mediator in Palestine to the United Nations, its leadership and its (1948), for his leadership in the armistice agreements organizations signed in 1949 by Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria 1954 Office of the United Nations High Commissioner 1957 for Refugees, Geneva, for its assistance to refugees Lester Pearson, Canada, ex-Secretary of State, President, 7th Session of the UN General Assembly, 1961 for a lifetime of work for peace and for leading UN Dag Hammarskjöld, Sweden, Secretary-General efforts to resolve the Suez Canal crisis of the UN, for his work in helping to settle the Congo crisis 1974 Sean MacBride, Ireland, UN Commissioner for 1965 Namibia Office of the United Nations High United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), for its Commissioner for Refugees, Geneva, for its work in helping save lives of the world's children assistance to European refugees . 1969 1994 International Labour Organisation (ILO), Geneva, for its progress in establishing workers' rights and Yasser Arafat , Chairman of the Executive protections Committee of the PLO, President of the Palestinian National Authority. Shimon Peres, Foreign Minister 1981 of Israel. Yitzhak Rabin, Prime Minister of Israel. for Office of the United Nations High Commissioner their efforts to create peace in the Middle East. for Refugees, Geneva, for its assistance to Asian refugees 1996 1988 Carlos Felipe Ximenes Belo and Jose Ramos-Hort United Nations Peace-keeping Forces, for its for their work towards a just and peaceful solution to peace-keeping operations the conflict in East Timor. -

Liste Der Nobelpreisträger

Physiologie Wirtschafts- Jahr Physik Chemie oder Literatur Frieden wissenschaften Medizin Wilhelm Henry Dunant Jacobus H. Emil von Sully 1901 Conrad — van ’t Hoff Behring Prudhomme Röntgen Frédéric Passy Hendrik Antoon Theodor Élie Ducommun 1902 Emil Fischer Ronald Ross — Lorentz Mommsen Pieter Zeeman Albert Gobat Henri Becquerel Svante Niels Ryberg Bjørnstjerne 1903 William Randal Cremer — Pierre Curie Arrhenius Finsen Bjørnson Marie Curie Frédéric John William William Mistral 1904 Iwan Pawlow Institut de Droit international — Strutt Ramsay José Echegaray Adolf von Henryk 1905 Philipp Lenard Robert Koch Bertha von Suttner — Baeyer Sienkiewicz Camillo Golgi Joseph John Giosuè 1906 Henri Moissan Theodore Roosevelt — Thomson Santiago Carducci Ramón y Cajal Albert A. Alphonse Rudyard \Ernesto Teodoro Moneta 1907 Eduard Buchner — Michelson Laveran Kipling Louis Renault Ilja Gabriel Ernest Rudolf Klas Pontus Arnoldson 1908 Metschnikow — Lippmann Rutherford Eucken Paul Ehrlich Fredrik Bajer Theodor Auguste Beernaert Guglielmo Wilhelm Kocher Selma 1909 — Marconi Ostwald Ferdinand Lagerlöf Paul Henri d’Estournelles de Braun Constant Johannes Albrecht Ständiges Internationales 1910 Diderik van Otto Wallach Paul Heyse — Kossel Friedensbüro der Waals Allvar Maurice Tobias Asser 1911 Wilhelm Wien Marie Curie — Gullstrand Maeterlinck Alfred Fried Victor Grignard Gerhart 1912 Gustaf Dalén Alexis Carrel Elihu Root — Paul Sabatier Hauptmann Heike Charles Rabindranath 1913 Kamerlingh Alfred Werner Henri La Fontaine — Robert Richet Tagore Onnes Theodore -

Sydney Institute of Agriculture Georgika

Sydney Institute of Agriculture Georgika Edition 3, December 2020 Georgika - an online newsletter for those interested in academic aspects of the Ag sector From the Director Alex McBratney Please enjoy the latest edition of Georgika where we highlight our research work in agriculture, our people and our ongoing links to our alumni and collaborators and stakeholders in the agricultural sector. This has been an unparalleled year in many ways – a pandemic and record yields on our farms. Something to remember forever. Some of us think the sooner we get to a new one the better. I’d like to thank everyone for all their diligent hard work over such a difficult year – despite the challenges I believe we are in a stronger position institutionally and nationally in relation to our agricultural effort, commitment, and standing than we were at the beginning of the year. So, I wish you a wonderful break. Take it – enjoy it. Wishing you a very happy and successful 2021 – it’s got to be better than this one. Distant links to Sydney I have been to loads of agriculture conferences around the world and we are often reminded of the phenomenal pioneering crop-breeding work of the Iowan, Norman Borlaug and his many colleagues and co-workers that led to his being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. Often this is stated as the first, and the only, Nobel prize in agriculture. In the nineteen twenties and thirties John Boyd Orr was Director of the Rowett Research Institute, famous for its work on animal nutrition. -

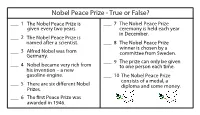

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

The Marriage of Health and Agriculture’

6. ‘The Marriage of Health and Agriculture’ Summary The year 1935 marked the pivotal point in McDougall’s thinking. This chapter begins with an account of the development of scientific knowledge of human nutritional needs in the early twentieth century, particularly in understanding the importance of vitamin-rich ‘protective foods’ such as dairy products, vegetables and fruit. Surveys following establishment of dietary standards in the 1920s showed that substantial proportions of populations, even in advanced countries, could not afford a diet adequate for health. Concerned doctors and scientists, including John Boyd Orr, sought action but were met with resistance from the British Government, which feared the cost. Measures to increase milk consumption were taken in Britain, but on grounds of assistance to the agricultural economy. In 1934 McDougall began to make the connection between poor nutrition and restrictive agricultural policies such as extreme protection. His suggestion for a campaign by scientists for adequate diets was enthusiastically supported by Orr, and by Bruce. McDougall completed his seminal memorandum, ‘The Agriculture and the Health Problems’, in early January 1935. This memorandum analysed the causes of agricultural problems, argued the benefits of improved nutrition and called for a reorientation of agricultural policy, meaning that industrial countries should concentrate on producing more of the protective foods, benefiting both consumers and producers. The ‘nutrition initiative’ was taken up by the International Labour Office at Geneva and the League of Nations; both passed resolutions calling for further investigation and action. The League established a ‘Mixed Committee’ of lay and specialist members, including McDougall, to report on nutrition to the 1936 Assembly and produced a four- volume report on the subject. -

The Beginner's Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize

THE BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO WINNING THE NOBEL PRIZE PETER DOHERTY AMERICAN EDITION Publisher: Columbia University Press ISBN 978-0-231-13897-0 CONTENTS 1 The Swedish Effect 2 The Science Culture 3 This Scientific Life 4 Immunity: A Science Story 5 Personal Discoveries and New Commitments 6 The Next American Century? 7 Through Different Prisms: Science and Religion 8 Discovering the Future 9 How to Win the Nobel Prize CHAPTER 1: The Swedish Effect The ceremonies surrounding the annual Nobel Prize presentations are for most Swedes an important reminder of great human endeavors, and of their own nation's place in promoting them. The awards have a high profile throughout the country: Swedish television carries live telecasts of the presentations and banquet, newspapers and radio programs feature the winners, and people talk about the prizes on the street. Until they win, few laureates realize that the award ceremony is associated with an intense but exhausting week that thrusts them suddenly into the media spotlight, and requires a high level of energy and – unless they are teetotal – a reasonably tolerant liver. When the king confers that award, handing the winner a gold medal and a leather-bound certificate in an atmosphere of solemn dignity, he also bestows a kind of celebrity status that has its own rewards and limitations. The latter mainly involves the loss of personal and professional time that goes with public attention, but the compensations are the broader awareness of your work, gaining a public 'voice' and the opportunities to meet extraordinary people. The presentation ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall is followed by the white-tie Nobel banquet – complete with gold-leafed plates and gold-plated cutlery – 1,200 in the town hall. -

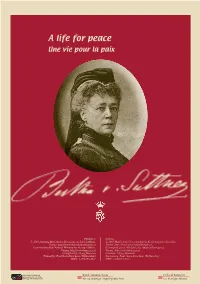

Leporello Engl+Franz->Gerin

EinA life Leben for peacefür den Frieden AUne life vie for pour peace la paix Publisher: Éditeur: © 2005 Austrian Museum for Economic an Social Affairs, © 2005 Musée Autrichien des Affairs Économiques et Sociales, Vienna, http://www.wirtschaftsmuseum.at Vienne, http://www.wirtschaftsmuseum.at Commissioned by: Federal Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Commandé par le Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, Vienna, http://www.bmaa.gv.at Vienne, http://www.bmaa.gv.at Compiled by: Georg Hamann Curateur: Georg Hamann Printed by: Paul Gerin Druckerei, Wolkersdorf Imprimerie: Paul Gerin Druckerei, Wolkersdorf ISBN: 3-902353-28-7 ISBN: 3-902353-28-7 ÖSTERREICHISCHES GESELLSCHAFTS- UND WIRTSCHAFTSMUSEUM 100th anniversary of Bertha von Suttner’s 100ème anniversaire du prix Nobel de la paix Nobel Peace Prize de Bertha von Suttner “Lay Down Your Arms!“ – The title of Bertha von Suttner´s most “Bas les armes!“ – Ce titre du roman le plus célèbre de famous novel was also the ambition and goal in life of this remarkable Bertha von Suttner fut aussi le but de sa vie et l’idée directrice de woman. The 100th anniversary of her award of the Nobel Peace toutes les action de cette femme remarquable. Le 100ème Prize is an excellent opportunity to remind us of her work and anniversaire de l’attribution du prix Nobel de la paix à Bertha von cause and to allow us to reflect upon it. Suttner est une excellente occasion de se souvenir de son oeuvre et d’y réfléchir. Bertha von Suttner was not only the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, she also inspired her friend and benefactor Non seulement elle fut la première femme à recevoir le prix Nobel Alfred Nobel to create the Nobel Peace Prize. -

The Role of Academies*

World Academy of Art & Science Eruditio, Issue 6 - Part 1, February 2015 The Role of Academies Ivo Šlaus ERUDITIO, Volume 1, Issue 6, February-April 2015, 01-07 The Role of Academies* Ivo Šlaus Honorary President, World Academy of Art and Science; Dean, Dag Hammarskjöld University College for International Relations & Diplomacy, Zagreb, Croatia Abstract Brief history of academies is presented, and the current role of academies is outlined. 1. Introduction Contemporary world is global, interdependent and rapidly changing.1 These features are occurring for the first time in human history. All of these features are science and technology generated. Present time can be best described by Charles Dickens’ opening sentence of his novel “The Tale of Two Cities” describing the times encompassing the French Revolution: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom and it was the age of foolishness, …. it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair…” The world is currently facing economic, political and moral crises. The only inexhaustible resource is knowledge. The most valuable capital is human (including social) capital, as shown by Sir Partha Dasgupta and his collaborators (see Table 1). The second column lists the real total capital of each nation and HC indicates the percentage due to human capital. Human capital includes health, education, freedom, creativity and activity of human beings, and once again science and curiosity-driven research play essential roles. Table 1: Real Wealth of Nations2 USA (2008) = $ 117.8 trillion (HC = 75%) UK = $ 13.4 (HC = 88%) Saudi Arabia = $ 4.9 (HC = 35%) Brazil = $ 7.4 (HC = 62%) Russian Federation = $ 10.3 (HC = 21%) “All men by nature desire to know” wrote Aristotle in his Metaphysics. -

The Liberal Moral Sensibility Writ Globally Contesting the Liberal Tradition in U.S

The Liberal Moral Sensibility Writ Globally Contesting the Liberal Tradition in U.S. Foreign Policy conference Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Amy L. Sayward Middle Tennessee State University January 2008 Rather than contesting the liberal tradition in U.S. foreign policy, I think that my research confirms the strength and vitality of that liberal tradition, which not only animated President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s thinking about the postwar world–which in many ways looked like his New Deal writ globally–but also came to animate the specialized agencies of the United Nations that he helped to create during World War II. But perhaps what I would like to add to the historiography is an explicit moral dimension. One of my colleagues, who is a cultural and intellectual historian, is writing about the rise at mid-twentieth century of a liberal moral sensibility–“an intellectual and moral framework that led to a particular set of actions and way of thinking.” This liberal moral sensibility–a descendant of the Progressive and Social Gospel movements that also had a formative fascination with science–sought to alleviate human suffering, embrace “personal autonomy and individual freedom as primary values,” and promote compassionate relationships.1 Shifted to the international sphere, this was what the specialized agencies were all about–using their expertise to alleviate suffering, promote a non-Communist agenda, and create a “new world” in which all countries felt a degree of responsibility for all other members of the community of nations. This is what I have termed the “birth of development,” when these relatively well equipped agencies “began working to better the lives 2 of other human beings whom they had never met nor known, for no reason other than the desire to improve the fate of the human race”2–in other words, when they crafted a liberal moral agenda for their work in the world. -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize. -

A Peace Odyssey Commemorating the 100Th Anniversary of the Awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize

CALL FOR PAPERS HOFSTRA CULTURAL CENTER in cooperation with THE PEACE HISTORY SOCIETY presents 2001: A Peace Odyssey Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize AN INTERDISCIPLINARY CONFERENCE THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY NOVEMBER 8, 9, 10, 2001 HEMPSTEAD, NEW YORK 11549 JEAN HENRI DUNANT, FRÉDÉRIC PASSY, ÉLIE RALPH BUNCHE, LÉON JOUHAUX, ALBERT SCHWEITZER, DUCOMMUN, CHARLES ALBERT GOBAT, SIR WILLIAM GEORGE CATLETT MARSHALL, THE OFFICE OF THE RANDAL CREMER, INSTITUT DE DROIT INTERNATIONAL, UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES, BARONESSPROBERTHAPACESOPHIE ETFELICITA VON SUTTNER, LESTER BOWLES PEARSON, GEORGES PIRE, PHILIP J. NÉEFCOUNTESSRATERNITATEKINSKY VON CHINIC UND TETTAU, NOEL-BAKER, ALBERT JOHN LUTULI, DAG HJALMAR THEODOREENTIUMROOSEVELT, ERNESTO TEODORO MONETA, AGNE CARL HAMMARSKJÖLD, LINUS CARL PAULING, LOUISGRENAULT, KLAS PONTUS ARNOLDSON, FREDRIK COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DE LA CROIX ROUGE, LIGUE BAJER(F, ORAUGUSTE THE PMEACEARIE FRANŸOIS AND BEERNAERT, PAUL DES SOCIÉTÉS DE LA CROIX-ROUGE, MARTIN LUTHER ROTHERHOOD OF EN HENRIB BENJAMIN BALLUET, BARONM D)E CONSTANT DE KING JR., UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND, RENÉ REBECQUE D'ESTOURNELLE DE CONSTANT, THE CASSIN, THE INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION, PERMANENT INTERNATIONAL PEACE BUREAU, TOBIAS N ORMAN ERNEST BORLAUG, WILLY BRANDT, MICHAEL CAREL ASSER, ALFRED HERMANN FRIED, HENRY A. KISSINGER, LE DUC THO, SEÁN E LIHU ROOT, HENRI LA FONTAINE, MACBRIDE, EISAKU SATO, ANDREI COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DE LA DMITRIEVICH SAKHAROV, B ETTY CROIX ROUGE, THOMAS