Eight Arms, with Attitude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHELKS Scientific Names: Busycon Canaliculatum Busycon Carica

Colloquial Nicknames: Channeled Whelk Knobbed Whelk WHELKS Scientific names: Busycon canaliculatum Busycon carica Field Markings: The shell of open with their strong muscular foot. As both species is yellow-red or soon as the valves open, even the tiniest orange inside and pale gray amount, the whelk wedges in the sharp edge outside. of its shell, inserts the proboscis and Size: Channeled whelk grows up devours the soft body of the clam. to 8 inches long; knobbed whelk Mating occurs by way of internal grows up to 9 inches long and 4.5 inches wide fertilization; sexes are separate. The egg casing of the whelk is a Habitat: Sandy or muddy bottoms long strand of yellowish, parchment-like disks, resembling a Seasonal Appearance: Year-round necklace - its unique shape is sculpted by the whelk’s foot. Egg cases can be two to three feet long and have 70 to 100 capsules, DISTINGUISHING FEATURES AND each of which can hold 20 to 100 eggs. Newly hatched channeled BEHAVIORS whelks escape from small holes at the top of each egg case with Whelks are large snails with massive shells. The two most their shells already on. Egg cases are sometimes found along common species in Narragansett Bay are the knobbed whelk the Bay shoreline, washed up with the high tide debris. and the channeled whelk. The knobbed whelk is the largest marine snail in the Bay. It Relationship to People is pear-shaped with a flared outer lip and knobs on the shoulder Both channeled and knobbed whelks scavenge and hunt for of its shell. -

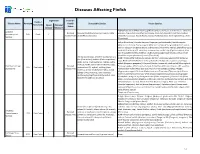

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

CHEMICAL STUDIES on the MEAT of ABALONE (Haliotis Discus Hannai INO)-Ⅰ

Title CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INO)-Ⅰ Author(s) TANIKAWA, Eiichi; YAMASHITA, Jiro Citation 北海道大學水産學部研究彙報, 12(3), 210-238 Issue Date 1961-11 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/23140 Type bulletin (article) File Information 12(3)_P210-238.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INo)-I Eiichi TANIKAWA and Jiro YAMASHITA* Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University There are about 90 existing species of abalones (Haliotis) in the world, of which the distribution is wide, in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Among the habitats, especially the coasts along Japan, the Pacific coast of the U.S.A. and coasts along Australia have many species and large production. In Japan from ancient times abalones have been used as food. Japanese, as well as American, abalones are famous for their large size. Among abalones, H. gigantea (" Madaka-awabi "), H. gigantea sieboldi (" Megai-awabi "), H. gigantea discus (" Kuro-awabi") and H. discus hannai (" Ezo-awabi") are important in commerce. Abalone is prepared as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or is cooked after cut ting it from the shell and trimming the visceral mass and then mantle fringe from the large central muscle which is then cut transversely into slices. These small steaks may be served at table as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or may be fried, stewed, or minced and made into chowder. A large proportion of the abalones harvested in Japan are prepared as cooked, dried and smoked products for export to China. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos

A Chave Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2017 Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (2017): Nomes galegos dos moluscos recomendados pola Chave. http://www.achave.gal/wp-content/uploads/achave_osnomesgalegosdos_moluscos.pdf 1 Notas introdutorias O que contén este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas). En total, achéganse nomes galegos para 534 especies de moluscos. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica que considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos. Aquí apúntase, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos que hai en cada familia. A seguir vén o corpo do documento, onde se indica, especie por especie, alén do nome científico, os nomes galegos e ingleses de cada molusco (nalgún caso, tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles). Ao final inclúese unha listaxe de referencias bibliográficas que foron utilizadas para a elaboración do presente documento. Nalgunhas desas referencias recolléronse ou propuxéronse nomes galegos para os moluscos, quer xenéricos quer específicos. Outras referencias achegan nomes para os moluscos noutras linguas, que tamén foron tidos en conta. Alén diso, inclúense algunhas fontes básicas a respecto da metodoloxía e dos criterios terminolóxicos empregados. 2 Tratamento terminolóxico De modo moi resumido, traballouse nas seguintes liñas e cos seguintes criterios: En primeiro lugar, aprofundouse no acervo lingüístico galego. A respecto dos nomes dos moluscos, a lingua galega é riquísima e dispomos dunha chea de nomes, tanto específicos (que designan un único animal) como xenéricos (que designan varios animais parecidos). -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Octopus Consciousness: the Role of Perceptual Richness

Review Octopus Consciousness: The Role of Perceptual Richness Jennifer Mather Department of Psychology, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: It is always difficult to even advance possible dimensions of consciousness, but Birch et al., 2020 have suggested four possible dimensions and this review discusses the first, perceptual richness, with relation to octopuses. They advance acuity, bandwidth, and categorization power as possible components. It is first necessary to realize that sensory richness does not automatically lead to perceptual richness and this capacity may not be accessed by consciousness. Octopuses do not discriminate light wavelength frequency (color) but rather its plane of polarization, a dimension that we do not understand. Their eyes are laterally placed on the head, leading to monocular vision and head movements that give a sequential rather than simultaneous view of items, possibly consciously planned. Details of control of the rich sensorimotor system of the arms, with 3/5 of the neurons of the nervous system, may normally not be accessed to the brain and thus to consciousness. The chromatophore-based skin appearance system is likely open loop, and not available to the octopus’ vision. Conversely, in a laboratory situation that is not ecologically valid for the octopus, learning about shapes and extents of visual figures was extensive and flexible, likely consciously planned. Similarly, octopuses’ local place in and navigation around space can be guided by light polarization plane and visual landmark location and is learned and monitored. The complex array of chemical cues delivered by water and on surfaces does not fit neatly into the components above and has barely been tested but might easily be described as perceptually rich. -

Freshwater Mussels "Do You Mean Muscles?" Actually, We're Talking About Little Animals That Live in the St

Our Mighty River Keepers Freshwater Mussels "Do you mean muscles?" Actually, we're talking about little animals that live in the St. Lawrence River called "freshwater mussels." "Oh, like zebra mussels?" Exactly! Zebra mussels are a non-native and invasive type of freshwater mussel that you may have already heard about. Zebra mussels are from faraway lakes and rivers in Europe and Asia; they travelled here in the ballast of cargo ships. When non-native: not those ships came into the St. Lawrence River, they dumped the originally belonging in a zebra mussels into the water without realizing it. Since then, particular place the zebra mussels have essentially taken over the river. invasive: tending to The freshwater mussels which are indigenous, or native, to the spread harmfully St. Lawrence River, are struggling to keep up with the growing number of invasive zebra mussels. But we'll talk more about ballast: heavy material that, later. (like stones, lead, or even water) placed in the bottom of a ship to For now, let's take a closer look at what it improve its stability means to be a freshwater mussel... indigenous: originally belonging in a particular place How big is a zebra mussel? 1 "What is a mussel?" Let's classify it to find out! We use taxonomy (the study of naming and classifying groups of organisms based on their characteristics) as a way to organize all the organisms of our world inside our minds. Grouping mussels with organisms that are similar can help us answer the question "What KKingdom:ingdom: AAnimalianimalia is a mussel?" Start at the top of our flow chart with the big group called the Kingdom: Animalia (the Latin way to say "animals"). -

Shellfish Hatchery

EAST HAMPTON TOWN SHELLFISH HATCHERY The 2015 Crew, left to right: Kate, Pete, Carissa, Shelby, and Barley 2015 ANNUAL REPORT AND 2016 OPERATING PLAN Prepared by Kate Rossi-Snook Edited by Barley Dunne East Hampton Town Shellfish Hatchery The skiff loaded for seeding in Lake Montauk Annual Report of Operations Mission Statement With a hatchery on Fort Pond Bay, a nursery on Three Mile Harbor, and a floating raft field growout system in Napeague Harbor, the East Hampton Town Shellfish Hatchery produces large quantities of oyster (Crassostrea virginica), clam (Mercenaria mercenaria), and bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) seed to enhance valuable shellfish stocks in local waterways. Shellfish are available for harvest by all permitted town residents. Cooperative research and experimentation concerning shellfish culture, the subsequent success of seed in the wild, and the status of the resource is undertaken and reported upon regularly, often funded and validated by scientific research grants. Educational opportunities afforded by the work include school group and open house tours and educational displays at community functions. Annual reporting includes production statistics and values, seed dissemination information, results of research initiatives, a summary of outreach efforts, the status of current and developing infrastructure, and a plan for the following year’s operations. 2015 Full-time Staff Part-time and Contractual Volunteers John “Barley” Dunne – Director Carissa Maurin – Environmental Aide Romy Macari Kate Rossi-Snook – Hatchery Manager Shelby Joyce – Environmental Aide (summer) Christopher Fox-Strauss Pete Topping – Algae Culturist Adam Younes – Environmental Aide (fall) Jeremy Gould – Maintenance Mechanic Carissa and Pete unloading OysterGros Special Thanks to: Barnaby Friedman for producing our annual seeding maps. -

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena Lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae)

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae) Date By From Version 2005 Leanne Hayter Ultimo TAFE v 1 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................ 5 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 CLASSIFICATION .............................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 GENERAL FEATURES ....................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 HISTORY IN CAPTIVITY ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 EDUCATION ..................................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH ........................................................................................................ 10 3 TAXONOMY ............................................................................................................................12 3.1 NOMENCLATURE ........................................................................................................................... 12 3.2 OTHER SPECIES ........................................................................................................................... -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

Shellfish Regulations

Town of Nantucket Shellfishing Policy and Regulations As Adopted on March 4, 2015 by Nantucket Board of Selectmen Amended March 23, 2016; Amended April 20, 2016 Under Authority of Massachusetts General Law, Chapter 130 Under Authority of Chapter 122 of the Code of the Town of Nantucket TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 – Shellfishing Policy for the Town of Nantucket/Purpose of Regulations Section 2 – General Regulations (Applying to Recreational, Commercial and Aquaculture Licenses) 2.1 - License or Permit Required 2.2 - Areas Where Recreational or Commercial Shellfishing May Occur 2.3 - Daily Limit 2.4 - Landing Shellfish 2.5 - Daily Time Limit 2.6 - Closures and Red Flag 2.7 - Temperature Restrictions 2.8 - Habitat Sensitive Areas 2.9 - Bay Scallop Strandings 2.10 - Poaching 2.11 - Disturbance of Licensed or Closed Areas 2.12 - Inspection on Demand 2.13 - Possession of Seed 2.14 - Methods of Taking 2.15 – SCUBA Diving and Snorkeling 2.16 - Transplanting, Shipping, and Storing of Live Shellfish 2.16a - Transplanting Shellfish Outside Town Waters 2.16b - Shipping of Live Shellfish for Broodstock Purposes 2.16c - Transplanting Shellfish into Town Waters 2.16d - Harvesting Seed from the Wild Not Allowed 2.16e - Wet Storage of Recreational Shellfish Prohibited. 2.17 - By-Catch 2.18 - Catch Reports Provided to the Town 2.18a - Commercial Catch Reports 2.18b - Recreational Catch Reports Section 3 – Recreational (Non-commercial) Shellfishing 3.1 - Permits 3.1a - No Transfers or Refunds 3.1b - Recreational License Fees 3.2 - Cannot Harvest for Commerce -

Spisula Solidissima) Using a Spatially Northeastern Continental Shelf of the United States

300 Abstract—The commercially valu- able Atlantic surfclam (Spisula so- Management strategy evaluation for the Atlantic lidissima) is harvested along the surfclam (Spisula solidissima) using a spatially northeastern continental shelf of the United States. Its range has con- explicit, vessel-based fisheries model tracted and shifted north, driven by warmer bottom water temperatures. 1 Declining landings per unit of effort Kelsey M. Kuykendall (contact author) (LPUE) in the Mid-Atlantic Bight Eric N. Powell1 (MAB) is one result. Declining stock John M. Klinck2 abundance and LPUE suggest that 1 overfishing may be occurring off Paula T. Moreno New Jersey. A management strategy Robert T. Leaf1 evaluation (MSE) for the Atlantic surfclam is implemented to evalu- Email address for contact author: [email protected] ate rotating closures to enhance At- lantic surfclam productivity and in- 1 Gulf Coast Research Laboratory crease fishery viability in the MAB. The University of Southern Mississippi Active agents of the MSE model 703 East Beach Drive are individual fishing vessels with Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 performance and quota constraints 2 Center for Coastal Physical Oceanography influenced by captains’ behavior Department of Ocean, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences over a spatially varying population. 4111 Monarch Way, 3rd Floor Management alternatives include Old Dominion University 2 rules regarding closure locations Norfolk, Virginia 23529 and 3 rules regarding closure du- rations. Simulations showed that stock biomass increased, up to 17%, under most alternative strategies in relation to estimated stock biomass under present-day management, and The Atlantic surfclam (Spisula solid- ally not found where average bottom LPUE increased under most alterna- issima) is an economically valuable temperatures exceed 25°C (Cargnelli tive strategies, by up to 21%.