Giant Pacific Octopus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diseases Affecting Finfish

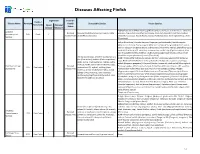

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

CHEMICAL STUDIES on the MEAT of ABALONE (Haliotis Discus Hannai INO)-Ⅰ

Title CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INO)-Ⅰ Author(s) TANIKAWA, Eiichi; YAMASHITA, Jiro Citation 北海道大學水産學部研究彙報, 12(3), 210-238 Issue Date 1961-11 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/23140 Type bulletin (article) File Information 12(3)_P210-238.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP CHEMICAL STUDIES ON THE MEAT OF ABALONE (Haliotis discus hannai INo)-I Eiichi TANIKAWA and Jiro YAMASHITA* Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University There are about 90 existing species of abalones (Haliotis) in the world, of which the distribution is wide, in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Among the habitats, especially the coasts along Japan, the Pacific coast of the U.S.A. and coasts along Australia have many species and large production. In Japan from ancient times abalones have been used as food. Japanese, as well as American, abalones are famous for their large size. Among abalones, H. gigantea (" Madaka-awabi "), H. gigantea sieboldi (" Megai-awabi "), H. gigantea discus (" Kuro-awabi") and H. discus hannai (" Ezo-awabi") are important in commerce. Abalone is prepared as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or is cooked after cut ting it from the shell and trimming the visceral mass and then mantle fringe from the large central muscle which is then cut transversely into slices. These small steaks may be served at table as raw fresh meat (" Sashimi") or may be fried, stewed, or minced and made into chowder. A large proportion of the abalones harvested in Japan are prepared as cooked, dried and smoked products for export to China. -

Southwest Guide: Your Use to Word

BEST CHOICES GOOD ALTERNATIVES AVOID How to Use This Guide Arctic Char (farmed) Clams (US & Canada wild) Bass: Striped (US gillnet, pound net) Bass (US farmed) Cod: Pacific (Canada & US) Basa/Pangasius/Swai Most of our recommendations, Catfish (US) Crab: Southern King (Argentina) Branzino (Mediterranean farmed) including all eco-certifications, Clams (farmed) Lobster: Spiny (US) Cod: Atlantic (gillnet, longline, trawl) aren’t on this guide. Be sure to Cockles Mahi Mahi (Costa Rica, Ecuador, Cod: Pacific (Japan & Russia) Cod: Pacific (AK) Panama & US longlines) Crab (Asia & Russia) check out SeafoodWatch.org Crab: King, Snow & Tanner (AK) Oysters (US wild) Halibut: Atlantic (wild) for the full list. Lobster: Spiny (Belize, Brazil, Lionfish (US) Sablefish/Black Cod (Canada wild) Honduras & Nicaragua) Lobster: Spiny (Mexico) Salmon: Atlantic (BC & ME farmed) Best Choices Mahi Mahi (Peru & Taiwan) Mussels (farmed) Salmon (CA, OR & WA) Octopus Buy first; they’re well managed Oysters (farmed) Shrimp (Canada & US wild, Ecuador, Orange Roughy and caught or farmed responsibly. Rockfish (AK, CA, OR & WA) Honduras & Thailand farmed) Salmon (Canada Atlantic, Chile, Sablefish/Black Cod (AK) Squid (Chile & Peru) Norway & Scotland) Good Alternatives Salmon (New Zealand) Squid: Jumbo (China) Sharks Buy, but be aware there are Scallops (farmed) Swordfish (US, trolls) Shrimp (other imported sources) Seaweed (farmed) Tilapia (Colombia, Honduras Squid (Argentina, China, India, concerns with how they’re Shrimp (US farmed) Indonesia, Mexico & Taiwan) Indonesia, -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Seaworld San Diego 2020 Fact Sheet

Media: For more information, contact SeaWorld Public Relations at (619) 225-3241 or [email protected] SEAWORLD SAN DIEGO 2020 FACT SHEET OVERVIEW: SeaWorld San Diego is one of the most popular marine parks in the world and a global leader in marine animal care and welfare, education, conservation, research and rescue. Through exciting and educational attractions, presentations, shows and exhibits, SeaWorld creates fun and meaningful experiences where guests can explore, become inspired to care about animals and wild wonders of the world, and to act to help protect them. SeaWorld San Diego, which opened in March of 1964, is one of 12 parks operated by SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. Every visit to a SeaWorld park helps support its animal rescue program. Seeing animals at SeaWorld supports saving them in the wild. DESCRIPTION: Spread across 190 acres on beautiful Mission Bay Park, SeaWorld San Diego is known for spectacular animal shows, interactive attractions, aquariums, rides, lush landscaping and education programs for all ages. Just in time for summer, the park will debut Emperor, California’s tallest, fastest and longest dive coaster. LOCATION: Off I-5 on SeaWorld Drive on Mission Bay, 10 minutes north of downtown San Diego, the San Diego International Airport and Amtrak’s downtown station. PARK HOURS: Opening and closing times vary by season. Hours are extended during seasonal periods, such as summer and winter holidays. Call (619) 222-4SEA or visit www.SeaWorldSanDiego.com. ADMISSION: $93.99, ages 10 and older; $88.99, ages 3–9; free, under 3. Annual Pass Memberships, the 2020 Fun Card and other ticket and Pass products make SeaWorld an even better value. -

Giant Pacific Octopus

Giant Pacific octopus − Enteroctopus dofleini Overall Vulnerability Rank = Low Biological Sensitivity = Low Climate Exposure = Low Sensitivity Data Quality = 50% of scores ≥ 2 Exposure Data Quality = 64% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Enteroctopus dofleini Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Low Habitat Specificity 2.0 2.5 Moderate High Prey Specificity 1.3 2.5 Very High Adult Mobility 2.3 2.0 Dispersal of Early Life Stages 1.9 1.7 Early Life History Survival and Settlement Requirements 2.6 0.8 Complexity in Reproductive Strategy 1.9 2.0 Spawning Cycle 1.9 1.7 Sensitivity to Temperature 1.3 2.8 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 2.0 3.0 Population Growth Rate 2.2 1.7 Stock Size/Status 1.5 1.2 Other Stressors 2.0 0.7 Sensitivity Score Low Sea Surface Temperature 2.0 2.0 Sea Surface Temperature (variance) 1.7 2.0 Bottom Temperature 2.1 2.0 Bottom Temperature (variance) 2.4 2.0 Salinity 1.1 2.0 Salinity (variance) 2.3 2.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Ocean Acidification (variance) 1.3 2.0 Phytoplankton Biomass 1.3 1.2 Phytoplankton Biomass (variance) 1.2 1.2 Plankton Bloom Timing 1.5 1.0 Plankton Bloom Timing (variance) 2.3 1.0 Large Zooplankton Biomass 1.1 1.0 Large Zooplanton Biomass (variance) 1.4 1.0 Exposure factors Exposure factors Mixed Layer Depth 1.8 1.0 Mixed Layer Depth (variance) 2.3 1.0 Currents 1.3 2.0 Currents (variance) 1.8 2.0 Air Temperature 2.0 2.0 Air Temperature (variance) 1.1 2.0 Precipitation NA NA Precipitation (variance) NA NA Sea Surface Height 2.0 2.0 Sea Surface Height (variance) 1.5 2.0 Exposure Score Low Overall Vulnerability Rank Low For assistance with this document, please contact NOAA Fisheries Office of Science and Technology at (301) 427-8100 or visit https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/contact/office-science-and-technology Giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: Low. -

2006 Reciprocal List

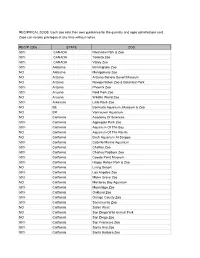

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Keep Calm . . . Explore, Discover and Learn New Things

Keep Calm . Explore, Discover and Learn new things NATURE Oakland Zoo’s Zoo@Home https://www.oaklandzoo.org/programs-and-events/zoo-at-home Zoo@Home allows you to experience all the educational opportunities from the comfort of your home! Continue where you left off at school with grade level appropriate activities and lessons. Safely enjoy nature and the outdoors while learning more about local wildlife. Learn all about the zoo animals and ask those questions you've always wondered. Even become a Jr. Zookeeper by creating enrichment for your pets at home. New content added weekly! (*thank you to Adrienne Mrsny for sharing this link and the many zoo/aquarium sites below) FloridaAquarium https://www.facebook.com/floridaaquarium/ https://www.flaquarium.org/s ea-span Sedgwick County Zoo Live Keeper Chats, Ambassador Animal Adventures www.facebook.com/SedgwickCountyZoo Elmwood Park Zoo, Zoo School: https://www.facebook.com/EPZoo/ Houston Zoo https://www.facebook.com/houstonzoo/ Brookfield Zoo, Keeper Chat https://www.facebook.com/BrookfieldZoo/ Virginia Zoo, Virtual Voyage https://www.facebook.com/thevirginiazoo/ In addition to social media updates, they will have several online resources listed on their website: virginiazoo.org/virtualvoyage Monterey Bay Aquarium will feature videos through Facebook Live: https://www.facebook.com/montereybayaquarium Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden, Home Safari, https://www.facebook.com/cincinnatizoo/ MUSEUMS Virtual Art Museum Tours https://www.travelandleisure.com/attractions/museums-galleries/museums-with-virtual-tours -

Freshwater Mussels "Do You Mean Muscles?" Actually, We're Talking About Little Animals That Live in the St

Our Mighty River Keepers Freshwater Mussels "Do you mean muscles?" Actually, we're talking about little animals that live in the St. Lawrence River called "freshwater mussels." "Oh, like zebra mussels?" Exactly! Zebra mussels are a non-native and invasive type of freshwater mussel that you may have already heard about. Zebra mussels are from faraway lakes and rivers in Europe and Asia; they travelled here in the ballast of cargo ships. When non-native: not those ships came into the St. Lawrence River, they dumped the originally belonging in a zebra mussels into the water without realizing it. Since then, particular place the zebra mussels have essentially taken over the river. invasive: tending to The freshwater mussels which are indigenous, or native, to the spread harmfully St. Lawrence River, are struggling to keep up with the growing number of invasive zebra mussels. But we'll talk more about ballast: heavy material that, later. (like stones, lead, or even water) placed in the bottom of a ship to For now, let's take a closer look at what it improve its stability means to be a freshwater mussel... indigenous: originally belonging in a particular place How big is a zebra mussel? 1 "What is a mussel?" Let's classify it to find out! We use taxonomy (the study of naming and classifying groups of organisms based on their characteristics) as a way to organize all the organisms of our world inside our minds. Grouping mussels with organisms that are similar can help us answer the question "What KKingdom:ingdom: AAnimalianimalia is a mussel?" Start at the top of our flow chart with the big group called the Kingdom: Animalia (the Latin way to say "animals"). -

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena Lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae)

Husbandry Manual for BLUE-RINGED OCTOPUS Hapalochlaena lunulata (Mollusca: Octopodidae) Date By From Version 2005 Leanne Hayter Ultimo TAFE v 1 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................ 5 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 CLASSIFICATION .............................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 GENERAL FEATURES ....................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 HISTORY IN CAPTIVITY ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 EDUCATION ..................................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 CONSERVATION & RESEARCH ........................................................................................................ 10 3 TAXONOMY ............................................................................................................................12 3.1 NOMENCLATURE ........................................................................................................................... 12 3.2 OTHER SPECIES ........................................................................................................................... -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

Feeding Ecology of Enteroctopus Megalocyathus (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) in Southern Chile Christian M

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2008, 88(4), 793–798. #2008 Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom doi:10.1017/S0025315408001227 Printed in the United Kingdom Feeding ecology of Enteroctopus megalocyathus (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae) in southern Chile christian m. ibanez~ 1 and javier v. chong2 1Instituto de Ecologı´a y Biodiversidad, Departamento de Ciencias Ecolo´gicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, PO Box 563, Santiago, Chile, 2Departamento de Ecologı´a Costera, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Cato´lica de la Santı´sima Concepcio´n, P.O. BOX 297, Concepcio´n, Chile In this research we studied the diet of Enteroctopus megalocyathus from three principal locations of the octopus fishery (Ancud, Quello´n and Melinka) in southern Chile. The gastric contents of 523 individuals, collected between October 1999 and September 2000, were examined and statistically analysed. Diet composition was described using detrended correspon- dence analysis and analysed as a function of predator gender, body size and fishing area. Food items were found in ~50% of the octopuses examined and a total of 14 prey items were recognized. The diet of E. megalocyathus consisted primarily in brachyuran and anomuran crustaceans, fish and conspecifics. The diet differed in composition between fishing zones and mantle length of the specimens and size of octopuses varied between locations. After adjusting for octopus mantle length, diet composition was found to be different between fishing areas. Large octopuses fed on large crabs at Ancud, while in Quello´n and Melinka small octopuses fed mainly on small crustaceans. There were no differences in prey composition between the gender and the size of octopuses was a better predictor of the variance in the diet composition (16%) than the fishing zone (6%).