The Bhakti Cycle of Assamese Lyrics: Bargits and After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books in the Library

u *r.4rArjFJr^ i Uh'.'i'',''' LIBRARY uNivdisnv ot ^ SAN DIEGO J CATALOGUE BENGALI PRINTED BOOKS LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. BY J. F. BLUMHARDT, FORMERLY OF THE BESG.U, CITIL SERVICE, TEACHER-CT BEXGALI IX THE UXITERSnT OF CAMBRIDGE ASD AT UXIVER-SITV COLLEGE, LOUDON. PRINTED BY OEDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEm. LONDON: SOLD BY LOXGMAXS & CO., 39, PATERJsOSTER ROTT; B. OTJARITCH, 15, PICCADILLY: A. ASHER & CO., 13, BEDFORD STREET, COVEXT GARDEJf, axd TRUBXER & CO., 57, LUDGATE HILL. 1886. STEPHEN AV6TIM AND SONS, PaiHTEBS, nEETFORD. The present Catalogue has been compiled by Mr. J. F. Blumhardt, formerly of the Bengal Civil Service, who has for several years been employed in cataloguing the works in the North Indian Vernaculars in the Museum Library. It is, perhaps, the first attempt that has been made to arrange Bengali writings under authors' names ; and the principles on which this has been done are fulh stated in the Preface. GEO. BULLEN, Keeper of the Department of Prdited Books. PEEFACE In submitting to the public the present Catalogue of Bengali books contained in the Library of the British Museum the compiler finds it necessary to explain the general principles of cataloguing adopted by him, and the special rules laid down for the treatment of Oriental names of authors and books. He has tried to observe throughout one consistent plan of transliteration, based on intelligible principles of etymology, yet rejecting alike the popular mode of writing names according to their modern pronunciation, and the pedantic system of referring everything back to its original Sanskrit form ; thereby making unnecessary deviations from proper Bengali idiom. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

Indian Medical Thought on the Eve of Colonialism

> Research & Reports Indian Medical Thought on the Eve of Colonialism London Library, Wellcome British colonial power decisively established itself on the Indian subcontinent between 1770 Research > and 1830. This period and the century following it have become the subjects of much South Asia creative and insightful research on medical history: the use of medical institutions and personnel as tools for political leverage and power; Anglicist/Orientalist debates surrounding medical education in Calcutta; the birth of so-called Tropical Medicine. Despite much propaganda to the contrary, European medicine did not offer its services in a vacuum. Long-established and sophisticated medical systems already existed in India, developing in new and interesting ways in the period just before the mid-eighteenth century. By Dominik Wujastyk to the present, laying bare for the first ring to the views of contemporary A physician and time the sheer volume and diversity of physicians. nurse attending a n recent years my research has the scientific production of the post- The second major influence on my sick patient and her Ifocused on the Sanskrit texts of clas- classical period. Production in no way research has been the recent work of servant. Watercolour. sical Indian medicine (Sanskrit: Ayurve- diminished in the sixteenth, seven- Sheldon Pollock, professor of Sanskrit seventeenth century. da, ‘the science of longevity’). System- teenth and eighteenth centuries, which at Chicago, and the invitation to partic- atic medical ideas, embodied in spawned rich and vitally important ipate in his ‘Indian Knowledge Systems ayurveda, began to be formulated at the medical treatises of all kinds. on the Eve of Colonialism’ project time of the Buddha (d. -

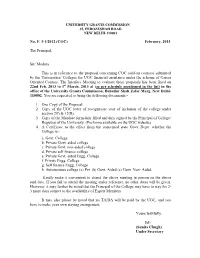

No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 the Principal

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 35, FEROZESHAH ROAD NEW DELHI-110001 No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 The Principal, Sir/ Madam, This is in reference to the proposal concerning COC (add-on courses) submitted by the Universities/ Colleges for UGC financial assistance under the scheme of Career Oriented Courses. The Interface Meeting to evaluate these proposals has been fixed on 22nd Feb, 2013 to 1st March, 2013 at (as per schedule mentioned in the list) in the office of the University Grants Commission, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi- 110002. You are requested to bring the following documents:- 1. One Copy of the Proposal. 2. Copy of the UGC letter of recognition/ year of inclusion of the college under section 2(f) & 12(B). 3. Copy of the Mandate form duly filled and duly signed by the Principal of College/ Registrar of the University. (Proforma available on the UGC website) 4. A Certificate to the effect from the concerned state Govt. Deptt. whether the College is:- a. Govt. College b. Private Govt. aided college c. Private Govt. non-aided college d. Private self finance college e. Private Govt. aided Engg. College f. Private Engg. College g. Self finance Engg. College h. Autonomous college (a) Pvt. (b) Govt. Aided (c) Govt. Non- Aided. Kindly make it convenient to attend the above meeting in person on the above said date. If you fail to attend the meeting under reference, no other dates will be given. However, it may further be noted that the Principal of the College may have to stay for 2- 3 more days subject to the availability of Expert Members. -

Worldwide Please Post in Your Temple

ISKCON - The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (Founder Acharya His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada) 2018 Newsletter WORLDWIDE PLEASE POST IN YOUR TEMPLE Harer nama harer nama harer namaiva kevalam kalau nasty eva nasty eva nasty eva gatir anyatha " In this age of quarrel and hypocrisy, the only means of deliverance is the chanting of the holy name of the Lord. There is no other way. There is no other way. There is no other way." Brhan-naradiya Puraṇa[38.126] Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare ataeva saba phala deha’ yāre tāre khāiyā ha-uk loka ajara amare Distribute this Krishna consciousness movement all over the world. Let people eat these fruits [of love of God] and ultimately become free from old age and death. Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu (CC, Adi-lila 9-39) Table Of Contents Editorial 1 by Lokanath Swami The Padayatra Ministry is recruiting 3 Why do I love padayatra? 4 by Gaurangi Dasi Padayatra Worldwide Ministry and Website 6 Voices of worldwide padayatris 7 Prabhupada on his morning walk 24th Czech padayatra 14 by Nrsimha Caitanya Dasa This newsletter is dedicated to ISKCON Founder-Acarya, Highlights of the 2017 All India Padayatra 17 His Divine Grace by Acarya Dasa A.C.Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. The Andhra Pradesh/Telangana padayatra 20 by Visnuswami Dasa “I am glad to learn that in Philadelphia they are increasing sankirtana. It is Bhaktimarga Swami’s walk across the US 21 our life and soul. Sankirtana should be increased as much as possible. -

GRADATION LIST of TEACHERS AS on 1St JULY 2017 SUBJECT: ENGLISH

1 MANGALORE UNIVERSITY GRADATION LIST OF TEACHERS AS ON 1st JULY 2017 SUBJECT: ENGLISH Sl. Name of the Teacher Designation Date of Qualification , Date of Total No. of Details of exp erience in Topics taught Courses Rem- No. Birth Specialization, and joining the teaching service at BOS, BOE, Pra. Exam. taught arks year of completion College Degree / Cordination P.G. level 1. Smt. S. Namita Tolpadi Associate 25.10.1958 M.A. Indian 05.07.1982 35 Years Member of BOS 3 Yrs, English Language, B.A./B.Com St. Mary’s Syrian College Professor Writing in English BOE Member 5 times, Optional Brahmavar. 1981 BOE Chairperson 2009 2. Dr. Sandhya R. Nambiar Principal 26.04.1958 M.A./Ph.D. 07.11.1983 34 Years BOE Member Twice II B.Com., I B.Sc., I, II, B.Sc. M.G.M. College P.G.D.E.S/LLB Chairperson 2015-16 III Opt. B.Com. Udupi. 3. Smt. Shakira Jabeen B. Associate 14.03.1958 MA PGDTE 25.10.1982 33 Years (2 Yrs. BOE Member 4 times English Language, Prose B.A./B.Com. Nehru Memorial College Professor Teacher Training BOS Member 2 times and Poetry Sullia. RIESI, Bangalore) 4. Dr. Ammalukutty M.P. Associate 21.08.1956 M.A./Ph.D. 22.08.1984 33 Years BOE, BOS English Language and B.A./B.Sc. University College Professor Literature B.Com. BBA Mangalore. 5. Sri Cyril Mathias Associate 14.01.1958 M.A. English 15.07.1985 33 Years BOE Member 2010, Optional English & B.A./B.Sc. -

The Many Faces of Ayurveda*

Ancient Science of Life, Vol No. XI No.3 & 4, January – April 1992, Pages 106 - 113 THE MANY FACES OF AYURVEDA* G. J. MEULENBELD De Zwaan 11, 9781 JX Bedum, The Netherlands *Speech delivered during the opening session of the Third International Congress of IASTAM, held at Bombay from 04 – 07 January, 1990. Received: 14 July 1990 Accepted: 9 December 1991 ABSTRACT: The erudite author makes an attempt in this article to trace the historical developments of Ayurveda. He also identifies the divergent views which made their appearance on the scene, thus highlighting the flexibility and adaptability of the system to ever changing circumstances. When one reads Sanskrit medical texts from is an arduous one. One way of facilitating various periods, one cannot but be struck by this insight is, in my view, the comparison a remarkable continuity of thought and of Ayurveda with other medical systems. practice on the one hand, and equally The most suitable counterpart of Ayurveda remarkable changes on the other. Just as for comparative purposes in Greek striking is the contrast between a tendency medicine, which resembles it in many towards consensus, and a tendency towards respects, being based on a humoral theory divergences in opinion. and having a long history. Since numerous authors, especially in our The beginnings of Ayurveda as a medical own times, have emphasized the unchanging system are more obscure than those of aspects of Ayurveda, it seems natural to Greek medicine. Indian medical literature study the other side of the coin as well. does not start with writings that are comparable with those of the Hippocratic To start with, I want to be clear about my corpus, which consists of a large number of point of departure in the study of Ayurveda treatises, embodying very diverse points of and its literature. -

Design Thinking Plausible Ancient Indian Alchemical Topical Drug Mechanism for Healing Wounds – a Mechanistic Approach

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 12 Ver II || Dec 2018 || PP 01-03 Design Thinking Plausible Ancient Indian Alchemical Topical Drug Mechanism for Healing Wounds – A Mechanistic Approach N.Anantha Krishna1, A.Raga Pallavi2 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Dr. KV SubbaReddy College of Engineering, Kurnool, India 2Department of H&S, Dr. KV SubbaReddy College of Engineering, Kurnool, India Corresponding Author:N.Anantha Krishna Abstract:Vanishing ancient technologies have in them a vast treasure of mystique methods or techniques that have to be researched to verify their compatibility with modern technologies. Of them, Alchemy, especially Indian alchemy has its own everlasting contribution in the fields of chemistry, material, science, medicine and metallurgy. These days, enough research attention has gathered around it and its mechanisms. However, only few have attempted to explore their possible/plausible healing mechanisms, especially, involving mechanistic philosophy, part and whole schema and design thinking- which is a novelty of this work. In this work,an endeavor is made to agglomerate the aforementioned philosophies for generic exploration of an ancient Indian alchemical topical application mentioned in anachronistic texts. Keywords:Honey,Mechanism, Reverse Engineering,Topical,Wounds, ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- -

Amlapitta (Gastritis)

ISSN: 2456-3110 REVIEW ARTICLE Jan-Feb 2017 A Critical Review of Disease Amlapitta (Gastritis) Pramod C. Baragi, 1 Umapati C. Baragi.2 1Professor & HOD, Dept. of Rasashastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, 2Reader, Dept. of Post Graduate Studies in Basic Principles, B.L.D.E.A’S, AVS, Ayurveda Mahavidhyalaya, Vijayapur, Karnataka, India. A B S T R A C T Survival of an organism on the earth is always challenged by the nature. Hunger, adverse climatic conditions, protection against wild animals and diseases are important amongst survival. Today due to modern life style and food habits most of the population are suffering from a common disease called as Gastritis. According to recent survey Gastritis is a common medical problem. Up to 10% of people, who come to a hospital emergency department with an abdominal pain, have gastritis. The incidence of gastritis in India is approximately 3 in 869 that is about 12,25,614 people suffering from gastritis out of the total 1,06,50,70,607 population. The seroprevalence studies from Delhi, Hyderabad and Mumbai have shown that by ten years of age more than 50% and by 20 years more than 80% of population is infected with gastritis. In Ayurveda this disease Gastritis is coined as Amlapitta. Here in this present paper Amlapitta disease is reviewed in detail according to Ayurvedic view and Modern view. Key words: Modern lifestyle, Gastritis, Hyperacidity, Amlapitta. INTRODUCTION The word ‘disease’ literally means lack of ease. common. According to Taber's encyclopaedic medical Historical Review dictionary, disease means “A pathological condition of To have a complete knowledge of subject, it is the body that presents a group of symptoms peculiar to it and that sets the condition apart as an abnormal necessary to trace out its historical background. -

Sri Caitanya-Mangala

Sri Caitanya-mangala Sutra-khanòa Vandanä Offering Obeisances Song 1 (Paöha-maïjari räga) 1. Obeisances, obeisances, obeisances to the saintly demigod Ganeça, who destroys all obstacles, who has a single tusk, who is stout, and who helps all auspicious projects. Glory, glory to Parvaté's son! 2. Folding my palms, I bow my head before Gauré and Çiva. Falling at their feet, I serve them. They are the creators of the three worlds. They are the givers of devotion to Lord Viñëu. They are all the gods and goddesses. 3. I bow my head before Goddess Sarasvaté. O goddess, please play on my tongue. Please give me many songs praising Lord Gaurahari, wonderful songs like nothing known in the three worlds. 4. With a voice choked with emotion, I beg: O spiritual masters, O demigods, please place no obstacles before me. I don't want money. I am an unimportant person. I want only that no obstacles will stop this book. 5. I bow down before the devotees of Lord Viñëu, devotees who are very fortunate, devotees whose virtues purify the whole earth, devotees who are merciful to everyone, devotees who love everyone, devotees whose pastimes bring auspiciousness to the three worlds. 6. I am worthless. I don't know right from left. I want to climb up and grab the sky. I am a blind man who wants to find a splendid jewel, even though I have no power to see even a mountain. What will become of me? I do not know. 7. There is but one hope. -

Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books in the Library of the British

»^i-^ t" uhc-YnVv^ \>i^'^€A \50o^v -aw^ ' r^is.. y ^v*\\'i?.>> riijseu^ ."Det^r, ,,(, A SUPPLEMENTAKY CATALOGUE OF BENGALI BOOKS\ IN THE LIBEAHY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM ACQUIRED DURING THE YEARS 188G-1910. COMPILED BY J. F. BLUMHARDT, M.A. PROFESSOR OF HINDUSTANI, AND LECTURER ON HINDI AND BENGALI AT UNrVEESITY COLLEGE, LONDON ; AND TEACHER OF BENGALI AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD. PBINTED BY OBDER OF THE TRUSTEES Hoiiion : SOLD AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM; AND BY LONGMANS & CO., 39, Paternoster Row; BERNARD QUARITCH, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, W. ; ASHER CO., 14, & Bedford Street, Covent Garden ; and HENRY FROWDE, Oxford University Press Warehouse, Amen Corner. 1910 [All rights reserved.'] : LoXBos PRINTED nv WILLIAJI OL"»ES AND SOXS, LIMITED, DDES STKEET, STAMFOllD STUEET, S.E., ASD GItEAT WINDMILL STKLET, tr. PEEFACE. This Catalogue of the Bengali Printed Books acquired by the Library of the British Museum during the years 1886—1910 has been prepared by Mr. Blumhardt as a supple- ment to the volume compiled by him and published by order of the Trustees in 1886. In the present catalogue a classified index of titles has been added ; in other respects the methods employed in the earlier volume have been closely followed in this work. L. D. BARNETT, Keeper cf Oriental Printrd Bouks and MSS. British Museum, AiKjusf 8, rjio. AUTHOE'S PREFACE. This Catalogue of Bengali l)ooks acquired during the last 24 years forms a supplement to the Bengali Catalogue published in 1886. It has been prepared on the same principles, and with the same system of transliteration. -

Report of a Second Tour in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts Made In

if^- IPfipi^ti:^ i:il,p:Pfiliif!f C\J CO 6605 S3B49 1907 c- 1 ROBA RErORT OK A SECOND TOUR IN EARCH OF SANSKRIT MANUSCRIPTS MADE IN- RAJPUTANA AND CENTRAL INDIA TN 1904-5 AND 1905-6. BY SHRIDHAR R. BHANDARKAB, M.A.^ Professor of SansTcrity FJiyhinstone Collegt. BOMBAY PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS 19C7 I'l'^'^Sf i^^s UBRA^ CCI2 , . 5 1995 'V- No. 72 OF 1906-07. Elphinsione College^ Bomhay^ 20lh February 1907. To The director op PUBLIC INSTRUCTION, Poona. Sir, * I have the honour to submit the following report of the tours I made through Central India and Rajputana in the beginning of 1905 and that of 1906 in accordance with the Resolutions of Government, Nos. 2321 and 660 in the Educational Department, dated the 14th December 1904 and 12th April 1905, respectively. 2. A copy of the first resolution reached me during the Christ- mas holidays of 1904^ but it was February before I could be relieved of my duties at College. So I started on my tour in February soon after I was relieved. 3. The place I was most anxious to visit first for several reasons was Jaisalmer. It lies in the midst of a sandy desert, ninety miles from the nearest railway station, a journey usually done on camel back. Dr. Biihler, who had visited the place in January 1874, had remarked about ^* the tedious journey and the not less tedious stay in this country of sand, bad water, and guinea-worms,'' and the Resident of the Western Rajputana States, too, whom I had seen in January 1904, had spoken to me of the very tedious and troublesome nature of the journey.