Reverse Commuting for the Baltimore Metropolitan Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

__History of Kew Depot and It's Routes

HISTORY OF KEW DEPOT AND ITS ROUTES Page 1 HISTORY of KEW DEPOT and the ROUTES OPERATED by KEW Compiled and written by Hugh Waldron MCILT CA 1500 The word tram and tramway are derived from Scottish words indicating the type of truck and the tracks used in coal mines. 1807 The first Horse tram service in the world commences operation between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales. 12th September 1854 At 12.20 pm first train departs Flinders Street Station for Sandridge (Port Melbourne) First Steam operated railway line in Australia. The line is eventually converted to tram operation during December 1987 between the current Southbank Depot and Port Melbourne. The first rail lines in Australia operated in Newcastle Collieries operated by horses in 1829. Then a five-mile line on the Tasman Peninsula opened in 1836 and powered by convicts pushing the rail vehicle. The next line to open was on 18/5/1854 in South Australia (Goolwa) and operated by horses. 1864 Leonard John Flannagan was born in Richmond. After graduating he became an Architect and was responsible for being the Architect building Malvern Depot 1910, Kew Depot 1915 and Hawthorn Depot 1916. He died 2nd November 1945. September 1873 First cable tramway in the world opens in Clay Street, San Francisco, USA. 1877 Steam tramways commence. Victoria only had two steam tramways both opened 1890 between Sorrento Pier to Sorrento Back Beach closed on 20th March 1921 (This line also operated horse trams when passenger demand was not high.) and Bendigo to Eaglehawk converted to electric trams in 1903. -

Star Transit Transit Development Plan: Fiscal Years 2010

SSTTAARR TTRRAANNSSIITT TTRRAANNSSIITT DDEEVVEELLOOPPMMEENNTT PPLLAANN:: FFIISSCCAALL YYEEAARRSS 22001100 –– 22001155 Prepared for: Prepared by: Under contract to: November 2009 Contents 1.0 STAR TRANSIT SYSTEM OVERVIEW ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 History ........................................................................................................................... 1‐1 1.2 Governance ................................................................................................................... 1‐2 1.3 Organizational Structure ............................................................................................... 1‐3 1.4 Transit Services Provided and Areas Served ................................................................. 1‐4 1.5 Fare Structure ................................................................................................................ 1‐9 1.6 Fleet ............................................................................................................................. 1‐10 1.7 Existing Facilities .......................................................................................................... 1‐10 1.8 Transit Security Program ............................................................................................. 1‐11 1.9 Public Outreach ........................................................................................................... 1‐11 2.0 GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND STANDARDS ........................................................................... -

Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Consultant’S Report (Final) July 2011

Barrier system (from TOA) Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Consultant’s Report (Final) July 2011 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION COUNTYWIDE BUS RAPID TRANSIT STUDY Consultant’s Report (Final) July 2011 Countywide Bus Rapid Transit Study Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key additional elements of BRT network ...................................................................... 2 1.1.1 Relationship to land use ........................................................................................ 2 1.1.2 Station access ...................................................................................................... 3 1.1.3 Brand identity ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Organization of report .................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ 5 2 Study Methodology ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 High-level roadway screening ...................................................................................... 9 2.2 Corridor development and initial -

Resolution #20-9

BALTIMORE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION BALTIMORE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION BOARD RESOLUTION #20-9 RESOLUTION TO ENDORSE THE UPDATED BALTIMORE REGION COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT – HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board (BRTB) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region, encompassing the Baltimore Urbanized Area, and includes official representatives of the cities of Annapolis and Baltimore; the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s; and representatives of the Maryland Departments of Transportation, the Environment, Planning, the Maryland Transit Administration, Harford Transit; and WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Baltimore region, has responsibility under the provisions of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act for developing and carrying out a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive transportation planning process for the metropolitan area; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration, a modal division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, requires under FAST Act the establishment of a locally developed, coordinated public transit-human services transportation plan. Previously, under MAP-21, legislation combined the New Freedom Program and the Elderly Individuals and Individuals with Disabilities Program into a new Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program, better known as Section 5310. Guidance on the new program was provided in Federal Transit Administration Circular 9070.1G released on June 6, 2014; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration requires a plan to be developed and periodically updated by a process that includes representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and participation by the public. -

Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy

TOLL FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES Bridges - Roads - Tunnels - Ferries August 2009 Publication No: FHWA-PL-09-00021 Internet: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/tollpage.htm Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy History The early settlers who came to America found a land of dense wilderness, interlaced with creeks, rivers, and streams. Within this wilderness was an extensive network of trails, many of which were created by the migration of the buffalo and used by the Native American Indians as hunting and trading routes. These primitive trails were at first crooked and narrow. Over time, the trails were widened, straightened and improved by settlers for use by horse and wagons. These became some of the first roads in the new land. After the American Revolution, the National Government began to realize the importance of westward expansion and trade in the development of the new Nation. As a result, an era of road building began. This period was marked by the development of turnpike companies, our earliest toll roads in the United States. In 1792, the first turnpike was chartered and became known as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania. It was the first road in America covered with a layer of crushed stone. The boom in turnpike construction began, resulting in the incorporation of more than 50 turnpike companies in Connecticut, 67 in New York, and others in Massachusetts and around the country. A notable turnpike, the Boston-Newburyport Turnpike, was 32 miles long and cost approximately $12,500 per mile to construct. As the Nation grew, so did the need for improved roads. -

Summary of the Current Revitalization of Brownfields Sites Where EPA

Report Date: 7 Feb 08 Summary of the Current Revitalization of Brownfields Sites where EPA Funded Targeted Brownfields Assessments (TBAs) Have Been Completed EPA Region III Compiled by Jerry Curtin (3HW51) Land Revitalization Team; Brownfields and Land Revitalization Branch 1 Items of Interest 1. The cover page shows the Stainless site in Perkasie, PA before a Targeted Brownfields Assessment (TBA) was performed (upper photo) and the site after a TBA and appropriate revitalization (lower photo). The site is discussed in Table A of this report, item 8. Over an 80year period, the site was used as an old site mill, a truck body manufacturing company and a stainless steel production facility. It is now the First Savings Bank Administrative Building. The cover photo is from the following website: http://www.gjdonovan.com/current.htm 2 Table of Contents Page A. Preface and Abbreviations 5 B. Background 9 C. Sites included in this report and their Table location 11 D. Results of the Evaluation 15 Table 1 Overall Revitalization Results 17 Table 2 Category of Revitalization for each site 18 E. Some of the Success Stories (Completely Redeveloped Sites) 19 F. Status of Sites 21 Table A: Completed TBAs and their status 23 Table B: Completed State Led SSAs and their status 39 Table C: Completed State SSAs overseen by the States 53 Table D: GAO specified TBAs199899 101 G. Acknowledgements 105 H. Photos of Some of the Success Stories 107 I. Maps: Locations of Sites in Each State 123 Enclosures/Attachments/Appendices In a Separate Document 3 4 A. -

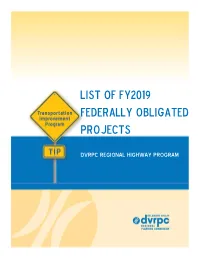

DVRPC FFY 2019 Annual Obligation Report Highway & Bridge

List of fy2019 federally obligated projects DVRPC REGIONAL HIGHWAY PROGRAM Date: 12/12/19 7:55AM FFY 2019 DVRPC TIP Page 1 of 12 Rpt # TIP302 FHWA Obligation Report Obligations 10/1/18 to 9/30/19 MPMS PROJECT TITLE PROJECT DESCRIPTION PROJECT ADMINISTRATOR PHASE DISTRICT COUNTY STATE ROUTE OBLIGATION* PROG. TOTAL FED FUNDS REMAINING FFY 2019 FFY 2019 TO 2022 110407 ADA Ramp STY (Districtwide) ADA Ramp Study PENNDOT Study 6 Bucks $300,000 $1,100,000 $800,000 Districtwide 87088 Chalfont Boro SRS(F) Chalfont Borough Safe Routes to School PENNDOT Construction 6 Bucks $(19,788) $0 $0 Pedestrian Facilities Chalfont Borough, Bucks County. 104302 Rt 13 Stscape Croydon Ph2(F) Route 13 Streetscape Croydon Section Phase 2 PENNDOT Construction 6 Bucks $90,000 $90,000 $0 Bristol Township, Bucks County Pedestrian Improvements 108002 Moland Park Trail (C) Moland Park Trail PENNDOT Construction 6 Bucks $500,000 $500,000 $0 Warwick Township Multi-use trail This project involves the creation of a pedestrian/bicycle trail under Route 263 to allow visitors access to recreational and cultural amenities near Moland Park. 102830 Neshaminy Greenway Trail (C) Neshaminy Greenway Trail (NGT) PENNDOT Construction 6 Bucks $2,000,000 $2,225,026 $225,026 New Britain Township, Bucks County Construction of the NGT 13549 US1: Old Linc - PA413 US Route 1: Old Lincoln - PA 413 PENNDOT Final Design 6 Bucks 1 $477,750 $15,925,000 $15,447,250 Bensalem and Middletown Townships, Bucks County Bridge Deck Rehabilitations 106989 SR 0001 @ SR 0032 Interchange (F) SR 0001 at SR 0032 Interchange PENNDOT Construction 6 Bucks 1 $250,000 $250,000 $0 Bucks County, Falls Twp. -

The Patapsco Regional Greenway the Patapsco Regional Greenway

THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the Patapsco Regional Greenway Concept Plan and Implementation Matrix is largely a community effort, the following individuals should be recognized for their input and contribution. Mary Catherine Cochran, Patapsco Heritage Greenway Dan Hudson, Maryland Department of Natural Resources Rob Dyke, Maryland Park Service Joe Vogelpohl, Maryland Park Service Eric Crawford, Friends of Patapsco Valley State Park and Mid-Atlantic Off-Road Enthusiasts (MORE) Ed Dixon, MORE Chris Eatough, Howard County Office of Transportation Tim Schneid, Baltimore Gas & Electric Pat McDougall, Baltimore County Recreation & Parks Molly Gallant, Baltimore City Recreation & Parks Nokomis Ford, Carroll County Department of Planning The Patapsco Regional Greenway 2 THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................4 2 BENEFITS OF WALKING AND BICYCLING ...............14 3 EXISTING PLANS ...............................................18 4 TREATMENTS TOOLKIT .......................................22 5 GREENWAY MAPS .............................................26 6 IMPLEMENTATION MATRIX .................................88 7 FUNDING SOURCES ...........................................148 8 CONCLUSION ....................................................152 APPENDICES ........................................................154 Appendix A: Community Feedback .......................................155 Appendix B: Survey -

Norristown Transportation Center to Graterford

SOUTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY SUBURBAN TRANSIT AND CONTRACT OPERATIONS ______________________________________ TARIFF NO. 155 SUPPLEMENT NO. 26 ______________________________________ LOCAL RATES OF FARE AND REGULATIONS GOVERNING THE FURNISHING OF PASSENGER TRANSPORTATION ON REGULAR SCHEDULED SERVICE ______________________________________ ISSUED: March 17, 2010 APPROVED: AMENDED: EFFECTIVE: ISSUED BY: Joseph M. Casey General Manager 1234 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19107-3780 CHANGES MADE BY THIS TARIFF 1. The title cover and related text in sections 3, 4, 10 and 20 has been changed from Suburban Transit Division to Suburban Transit and Contract Operations to reflect the nature of Suburban Transit routes operated by Victory and Frontier Districts, as well as transit services contracted to a private carrier. 2. Fare Zones are revised on the following routes as part of the FY 2012 Annual Service Plan: 92, 95, 98, 115, 119, 127, 130 and 139. New Routes 126 and 133 are included. Routes 304 and 314 would be discontinued. These fare zone changes would take effect upon SEPTA Board approval of the FY 2012 Annual Service Plan and funding availability. 3. Fare Zones are revised on the following routes as part of the FY 2011 Annual Service Plan: 97, 105 and 106. 4. Route 100 is now known as Norristown High Speed Line. 5. All references to 69th Street Terminal are changed to read 69th Street Transportation Center (69th Street TC). 6. Route 129 references to Torresdale have been updated to reflect what is printed on the public timetable and destination signs. 7. Fare zone information is revised for Routes 204, 205 and 306. 8. Information regarding Route 305 has been removed 9. -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Operations and Financial Analysis

OPERATIONS AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS APRIL 22, 2015 PREPARED BY: LOUIS BERGER WATER SERVICES TABLE OF CONTENTS A) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY B) OPERATIONS ANALYSIS C) FINANCIAL ANALYSIS D) APPENDICES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Louis Berger was tasked by the Baltimore City Department of Transportation (BCDOT) to evaluate the Charm City Circulator (CCC) bus operation and analyze financial performance, and develop route operations alternatives that maximize ridership while minimizing costs. Objective The objective is to develop and evaluate alternatives to eliminate the annual deficits while providing maximum service to riders within existing financial resources. Description of Current System Existing Condition The CCC consists of four routes, Purple, Orange, Green and Banner providing “Fast. Friendly. Free.” service throughout downtown Baltimore 362 days per year, with hours of service varying by day type and by season. Key characteristics of each route: Purple Route- runs north - south from Federal Hill to Historic Mount Vernon. Ten (10) minute headways require six (6) buses to operate. Heaviest ridership of all the routes. Orange Route- runs east – west from Historic Fell’s Point and Harbor Point in the east beyond University of Maryland, Baltimore in the west. Ten (10) minute headways require five (5) buses to operate. Ridership is second best in the system. Green Route- roughly U shaped route serves Johns Hopkins University Hospital East Baltimore Campus (JHUH) connecting south to Harbor Point and Harbor East, then northwest to park and ride lots, looping down near City Center then back around. Ten (10) minute headways require six (6) buses. Longest route, least productive in terms of riders. Banner Route- angles southeast of the city past Federal Hill to Fort McHenry. -

Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction

VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW ________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 73 OCTOBER 2020 NUMBER 5 ________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLES “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes”*: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction Deborah N. Archer** Racial and economic segregation in urban communities is often understood as a natural consequence of poor choices by individuals. In reality, racially and economically segregated cities are the result of many factors, * “White men’s roads through black men’s homes” was the mantra of a coalition led by Reginald M. Booker and Sammie Abbott in opposition to highway development in Washington, D.C. See Harry Jaffe, The Insane Highway Plan that Would Have Bulldozed DC’s Most Charming Neighborhoods, WASHINGTONIAN (Oct. 21, 2015), https://www.washingtonian.com/2015/10/21/the- insane-highway-plan-that-would-have-bulldozed-washington-dcs-most-charming-neighborhoods/ [https://perma.cc/6YCR-PKKR] (discussing the campaign to halt the building of highways in Washington, D.C.). ** Associate Professor of Clinical Law and Co-Faculty Director of the Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law, New York University School of Law. I thank Rachel Barkow, Richard Buery, Audrey McFarlane, Michael Pinard, Russell Robinson, Sarah Schindler, Tony Thompson, Kele Williams, and Katrina Wyman for helpful comments on earlier drafts. I also appreciate the insights I received from participants of faculty workshops at Brooklyn Law School and the University of Miami School of Law and participants at the 2019 Clinical Law Review Workshop at NYU Law School. I am grateful to Nelson Castano, Anna Applebaum, Michael Milov-Cordoba, and Rachel Sommer for their research assistance and to Sarah Jaramillo for her constant support of my research.