Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

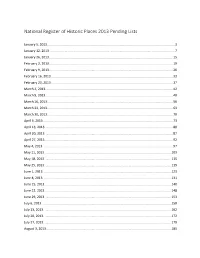

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2013 Pending Lists January 5, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 12, 2013. .......................................................................................................................................... 7 January 26, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 February 2, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 February 9, 2013. ........................................................................................................................................ 26 February 16, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 33 February 23, 2013. ...................................................................................................................................... 37 March 2, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 42 March 9, 2013. ............................................................................................................................................ 48 March 16, 2013. ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

CE-1529 Elk Neck State Park

CE-1529 Elk Neck State Park Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 11-26-2018 Addendum to Inventory No. CE-1529 Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form Page 1 of 1 Name of Property: Elk Neck State Park Location: Elk Neck Peninsula The following is an update to the "Table of Resources" inventoried at Elk Neck State Park in 2003: MIHP Number Name Condition as of April 2018 CE-1529 Elk Neck State Park, Wersen House Razed, date unknown CE-813 located within CE-1529 Bathon Stone House Razed, 2012 Bathon Barn Razed,2012 -

Draft National Mall Plan / Environmental Impact Statement the National Mall

THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT DRAFT NATIONAL MALL PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT THE NATIONAL MALL THE MALL CONTENTS: THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................... 249 Context for Planning and Development of the National Mall ...................................................................251 1790–1850..................................................................................................................................................251 L’Enfant Plan....................................................................................................................................251 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................252 1850–1900..................................................................................................................................................253 The Downing Plan...........................................................................................................................253 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................253 1900–1950..................................................................................................................................................254 The McMillan Plan..........................................................................................................................254 -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

FORD MANSION Day

THE UPSTAIRS HALL As you enter the hall, notice the three Pennsylvania low-back Windsor chairs, circa 1750. These In this large hallway most of the winter's social activities are the earliest known American- took place. According to family tradition, the large camp chest style Windsor. to your left was left by Washington as a gift to Mrs. Ford. The folding cot would have been used by "Will," Washington's favorite servant, who as a matter of custom, slept close to the WASHINGTON'S CONFERENCE AND DINING ROOM General's bedroom. In this room the daily activities of Washington's staff were . Proceed to the next room on performed. Washington also used this room to meet with your left. officers and citizens. At 3 p.m. daily, Washington, Mrs. Washington, his staff, and guests began the main meal of the FORD MANSION day. At least three courses were served, and the meal took in THE AIDES' AND GUESTS' ROOM excess of two hours to consume. But much of that time was used to informally discuss military topics, such as supply, Most of Washington's aides slept in this room as evidenced by recruitment, and strategy for the spring campaign. the number of folding cots and traveling chests. However, when important guests came to the House, the aides moved Of special interest is the Chippendale desk thought to have into other quarters. In May of 1780, LaFayette stayed here as been here during the winter of 1779-80. Also observe the had the Spanish Ambassador Don Juan De Miralles. Chippendale mirror, a Ford family piece, with a Phoenix bird Unfortunately, De Miralles died while here as a guest of the arising from the top. -

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Jockey Hollow, Morristown National

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 1999 Jockey Hollow Morristown National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Jockey Hollow Morristown National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, -

2011 DIRECTORY of the Colonial Dames of America in the State Of

2010 - 2011 DIRECTORY of The Colonial Dames of America in The State of Connecticut THE CONNECTICUT SOCIETY HEADQUARTERS The Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum 211 Main Street, Wethersfield, Connecticut 06109-2339 Phone: 860-529-0612; Barn Phone: 860-529-4552 Fax: 860-571-8636; E-mail: [email protected] Websites: www.webb-deane-stevens.org www.silasdeaneonline.org; www.revolutionaryct.org Museum Hours: May 1 - October 31, weekdays except Tuesday, 10:00-4:00 p.m.; Saturdays 10-4 p.m., Sundays, 1-4 p.m. November 1 - April 30, weekends only: Saturdays 10:00-4:00 p.m., Sundays, 1-4:00 p.m Clsed January-March Office Hours: 9-4 p.m. Monday-Friday Printed September 1, 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS National Society Mission ………………….……………………………………. 3 Officers…………………………………………………. ... .. 3 Dumbarton House (Headquarters)………………………… 3 Gunston Hall …………………………………………………. 4 Sulgrave Manor ……………………………………………… 4 National Roll of Honor……………………………………… 5 State Society 5 Advisory Committee ……………..………………….….…… 8 Board of Managers …..……………………………………... 9 Calendar for 2010-2011 …………………………………..… 57-58 Committees ………………………………………………….. 10 Areas………………………………………………………….. 16 Audit 10 Collections……………………………………………………. 10 Development…………………………………………………. 10 Executive……………………………………………………… 11 Finance……………..………………………………………… 11 Garden Angels……………………………………………….. 12 Grounds……………….……………………………………… 11 Historical Activities…………………………………………… 12 Library………………………………………………………… 12 Membership………………………….…………………….… 13 Museum Building Committee………………………………. 13 Nominating………………………….………………………… 13 Patriotic -

Master Plan, Adopted on December 5,2001

Phone 732-329-4000 TOWNSHIP OF SOUTH BRUNSWICK TOO 732-329-2017 Municipal Building Monmouth Junction, NJ 08852 TO THE GOVERNING BODY AND THE CITIZENS OF THE TOWNSHIP OF SOUTH BRUNSWICK: On behalf of the South Brunswick Township Planning Board, it is my honor and privilege to present the 2001 Master Plan, adopted on December 5,2001. The policies incorporated into this Master Plan are the result of a two-year study by the Planning Board, assisted by its Master Plan Sub-Committee, Consultants, and Planning Department Staff. In addition, various committees, boards, and commissions involved with the process have held numerous meetings and given many hours of their time in the review and formulation of the Master Plan. The Planning Board expresses its sincere appreciation to our Mayor, Township Council, Township agencies, citizens and professional staff for their time and assistance in the preparation of the Master Plan. This Master Plan is a logical and workable guide, which represents our vision for the future development of South Brunswick Township for the decade of 2000. Susan Edelman, Chairperson 2001 MASTER PLAN Township of South Brunswick Middlesex County, New Jersey Adopted December 5, 2001 Prepared by HeHeHeyyyererer,,, Gruel & Associates PAAA CommCommCommunity Planning Consultants 63 Church Street, 2nd Floor New Brunswick, NJ 08901 732-828-2200 Historic Survey Prepared by Hunter Research Housing Element & Fair Share Plan Prepared by South Brunswick Township Planning Staff 2001 Comprehensive Master Plan Township Wide Circulation Element Prepared by Alaimo Group, Alexander Litwornia and Associates The original of this report was signed and sealed in accordance with N.J.S.A. -

Papers of the American Slave Trade

Cover: Slaver taking captives. Illustration from the Mary Evans Picture Library. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of the American Slave Trade Series A: Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society Part 2: Selected Collections Editorial Adviser Jay Coughtry Associate Editor Martin Schipper Inventories Prepared by Rick Stattler A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society [microfilm] / editorial adviser, Jay Coughtry. microfilm reels ; 35 mm.(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Contents: pt. 1. Brown family collectionspt. 2. Selected collections. ISBN 1-55655-650-0 (pt. 1).ISBN 1-55655-651-9 (pt. 2) 1. Slave-tradeRhode IslandHistorySources. 2. Slave-trade United StatesHistorySources. 3. Rhode IslandCommerce HistorySources. 4. Brown familyManuscripts. I. Coughtry, Jay. II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Rhode Island Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. VI. Series. [E445.R4] 380.14409745dc21 97-46700 -

Assessing Hisoroty

Philadelphia as a Civil War Era History Destination Assessing Interest and Preferences Among Potential Visitors Report of Results of Phase 3 of Market Research Prepared for: The Civil War History Consortium June 2006 2002 Ludlow Street, First Floor / Philadelphia, PA 19103 / 215-545-0054 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. RESEARCH BACKGROUND AND APPROACH....................................................................1 A. Objectives..................................................................................................................................1 B. Research Approach..................................................................................................................3 II. KEY FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS ...................................................................................4 III. RECOMMENDATIONS.............................................................................................................11 IV. DETAILED FINDINGS ..............................................................................................................13 A. Survey Population..................................................................................................................13 B. Experiences of the “History Visitor”....................................................................................19 C. Visits to Civil War-related Sites ...........................................................................................26 D. Interest in Philadelphia as Civil War History Destination ................................................32 -

Oliver Evans (Edited from Wikipedia)

Oliver Evans (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY Oliver Evans (September 13, 1755 – April 15, 1819) was an American inventor, engineer and businessman born in rural Delaware and later rooted commercially in Philadelphia. He was one of the first Americans building steam engines and an advocate of high pressure steam (vs. low pressure steam). A pioneer in the fields of automation, materials handling and steam power, Evans was one of the most prolific and influential inventors in the early years of the United States. He left behind a long series of accomplishments, most notably designing and building the first fully automated industrial process, the first high-pressure steam engine, and the first (albeit crude) amphibious vehicle and American automobile. Born in Newport, Delaware, Evans received little formal education and in his mid-teens was apprenticed to a wheelwright. Going into business with his brothers, he worked for over a decade designing, building and perfecting an automated mill with devices such as bucket chains and conveyor belts. In doing so Evans designed a continuous process of manufacturing that required no human labor. This novel concept would prove critical to the Industrial Revolution and the development of mass production. Later in life Evans turned his attention to steam power, and built the first high-pressure steam engine in the United States in 1801, developing his design independently of Richard Trevithick, who built the first in the world a year earlier. Evans was a driving force in the development and adoption of high-pressure steam engines in the United States. Evans dreamed of building a steam-powered wagon and would eventually construct and run one in 1805.