A Crucible of the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

Bicentennial Source Book, Level I, K-2. INSTITUTION Carroll County Public Schools, Westminster, Md

--- I. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 106 189 S0,008 316 AUTHOR _Herb, Sharon; And Others TITLE Bicentennial Source Book, Level I, K-2. INSTITUTION Carroll County Public Schools, Westminster, Md. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 149p.; For related guides, see CO 008'317-319 AVAILABLE FROM .Donald P. Vetter, Supervisor of Social Studies, Carroll County Board of Education, Westsinister, Maryland 21157 ($10.00; Set of guides.I-IV $50:00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0..76 HC-Not Available from EDRS..PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *American Studies; Class Activities; *Colonial History (United States); Cultural Activities; Elementary Education; I structionalMaterials; *Learning Activities; Muc Activities; Resource Materials; Revolutionary Wa (United States); Science Activities; *Social Studies; Icher Developed Materials; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial ABSTRACT This student activities source book ii'one of a series of four developed by the Carroll County Public School System, Maryland, for celebration of the Bicentennial. It-is-specifically designed to generate ideas integrating the Bicentennial celebration into various disciplines, classroom activitiese.and school -vide 4vents at the kindergarten through second grade levels. The guide contains 81 activities related to art, music, physical-education, language arts, science, and social studies. Each activity includes objectives, background information, materials and resources, recommended instructional proce ures,and possible variations and modifications. The activities are organized around the Bicentennial themes of Heritage, Horizons, and Festival. Heritage. activities focus on events, values, traditionp, and historical objects of the past. Horizon activities stress challenging the problems of the present and future. Festival activities include such activities as community craft shows, workshops, folk music, and dance performances. (Author /ICE) C BICENTENNIAL SOURCE BOOK LEVEL I . -

Historic Furnishings Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey

~~e, ~ t..toS2.t.?B (Y\D\L • [)qf- 331 I J3d-~(l.S National Park Service -- ~~· U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Furnishings Assessment Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey Decemb r 2 ATTENTION: Portions of this scanned document are illegible due to the poor quality of the source document. HISTORIC FURNISHINGS ASSESSMENT Ford Mansion and Wic·k House Morristown National Historical Park Morristown, New Jersey by Laurel A. Racine Senior Curator ..J Northeast Museum Services Center National Park Service December 2003 Introduction Morristown National Historical Park has two furnished historic houses: The Ford Mansion, otherwise known as Washington's Headquarters, at the edge of Morristown proper, and the Wick House in Jockey Hollow about six miles south. The following report is a Historic Furnishings Assessment based on a one-week site visit (November 2001) to Morristown National Historical Park (MORR) and a review of the available resources including National Park Service (NPS) reports, manuscript collections, photographs, relevant secondary sources, and other paper-based materials. The goal of the assessment is to identify avenues for making the Ford Mansion and Wick House more accurate and compelling installations in order to increase the public's understanding of the historic events that took place there. The assessment begins with overall issues at the park including staffing, interpretation, and a potential new exhibition on historic preservation at the Museum. The assessment then addresses the houses individually. For each house the researcher briefly outlines the history of the site, discusses previous research and planning efforts, analyzes the history of room use and furnishings, describes current use and conditions, indicates extant research materials, outlines treatment options, lists the sources consulted, and recommends sourc.es for future consultation. -

Historical Study Guide

Historical Study Guide Light A Candle Films presents “THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL” Historical Study Guide written by Tony Malanowski To be used with the DVD production of THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL The Battle of Bunker Hill Historical Study Guide First, screen the 60-minute DocuDrama of THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, and the 30 minute Historical Perspective. Then, have your Discussion Leader read through the following historical points and share your ideas about the people, the timeframe and the British and Colonial strategies! “Stand firm in your Faith, men of New England” “The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die.” - George Washington, August 27, 1776 When General Thomas Gage, the British military governor of Boston, sent one thousand troops to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock at Lexington in April of 1775, he could not know the serious implications of his actions. Nor could he know how he had helped to set in motion a major rebellion that would shake the very foundations of the mightiest Empire on earth. General Gage was a military man who had been in North America since the 1750s, and had more experience than any other senior British officer. He had fought in the French and Indian War alongside a young George Washington, with whom he still had a friendly relationship. Gage had married an American woman from a prominent New Jersey family, and 10 of their 11 children had been born in the Colonies. -

In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June

Official Publication of the WA State, Alexander Hamilton Chapter, SAR Volume V, Issue 6 (June 2019) Editor Dick Motz In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June .................. 2 Alexander Hamilton Trivia? ............................ 2 Message from the President ........................... 2 What is the SAR? ............................................ 3 Reminders ..................................................... 3 Do you Fly? .................................................... 3 June Birthdays ............................................... 4 Northern Region Meeting Activities & Highlights ....................... 4 Chapter Web Site ........................................... 5 20 July: West Seattle Parade Member Directory Update ............................. 5 Location: West Seattle (Map Link). Wanted/For Sale ............................................ 6 Southern Region Battles of the Revolutionary War Map ............ 6 4 July: Independence Day Parade Location: Steilacoom (Map Link). Plan ahead for these Special Dates in July 17 Aug: Woodinville Parade 4 Jul: Independence Day Location: Woodinville (Map Link) 6 Jul: International Kissing Day 6 Jul: National fried Chicken Day 2 Sep: Labor Day Parade (pending) 17 Jul: National Tattoo Day Location: Black Diamond (Map Link) 29 Jul: National Chicken Wing Day 15-16 Sep: WA State Fair Booth Location: Puyallup 21 Sep: Chapter meeting Johnny’s at Fife, 9:00 AM. 9 Nov: Veterans Day Parade Location: Auburn (Map Link) 14 Dec: Wreaths Across America Location: JBLM (Map -

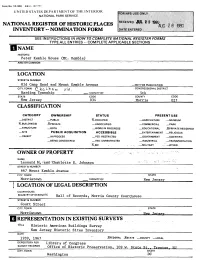

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Peter Kemble House (Ht. Kemble)______________________________ AND/OR COMMON ~ ~ ~ ~ '• ~' ~ T LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Old Camp Road and Mount Kemble Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIpNAL DISTRICT Harding Township VICINITY OF 5th STATE CODE COUNTY New Jersey 034 Morris CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL JXPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION ——MILITARY OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Leonard M. ^rid "Cha)ri<:>tte S. Johnson STREET & NUMBER 667 Mount Kemble-Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Morris town VICINITY OF New Jersey LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF of Records, Morris County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Court Street CITY, TOWN STATE New REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey _____New Jersey Historic Sites Inventory_____________ DATE 1939, 1967 __ ^FEDERAL J^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR Library of Congress SURVEY RECORDS Office of Historic Preservation, 109 W. State St. f Trenton, NJ CITY. TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE ^_GOOD —RUINS 2LALTERED 2LMOVED DATE_18AHis —FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Exterior The Kemble House is a five bay clapboard building with a center hall. -

Henry Clinton Papers, Volume Descriptions

Henry Clinton Papers William L. Clements Library Volume Descriptions The University of Michigan Finding Aid: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsead/umich-wcl-M-42cli?view=text Major Themes and Events in the Volumes of the Chronological Series of the Henry Clinton papers Volume 1 1736-1763 • Death of George Clinton and distribution of estate • Henry Clinton's property in North America • Clinton's account of his actions in Seven Years War including his wounding at the Battle of Friedberg Volume 2 1764-1766 • Dispersal of George Clinton estate • Mary Dunckerley's account of bearing Thomas Dunckerley, illegitimate child of King George II • Clinton promoted to colonel of 12th Regiment of Foot • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot Volume 3 January 1-July 23, 1767 • Clinton's marriage to Harriet Carter • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton's property in North America Volume 4 August 14, 1767-[1767] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Relations between British and Cherokee Indians • Death of Anne (Carle) Clinton and distribution of her estate Volume 5 January 3, 1768-[1768] • Matters concerning 12th Regiment of Foot • Clinton discusses military tactics • Finances of Mary (Clinton) Willes, sister of Henry Clinton Volume 6 January 3, 1768-[1769] • Birth of Augusta Clinton • Henry Clinton's finances and property in North America Volume 7 January 9, 1770-[1771] • Matters concerning the 12th Regiment of Foot • Inventory of Clinton's possessions • William Henry Clinton born • Inspection of ports Volume 8 January 9, 1772-May -

Continental Army: Valley Forge Encampment

REFERENCES HISTORICAL REGISTRY OF OFFICERS OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY T.B. HEITMAN CONTINENTAL ARMY R. WRIGHT BIRTHPLACE OF AN ARMY J.B. TRUSSELL SINEWS OF INDEPENDENCE CHARLES LESSER THESIS OF OFFICER ATTRITION J. SCHNARENBERG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION M. BOATNER PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN D. MARTIN AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE DELAWARE VALLEY E. GIFFORD VALLEY FORGE J.W. JACKSON PENNSYLVANIA LINE J.B. TRUSSELL GEORGE WASHINGTON WAR ROBERT LECKIE ENCYLOPEDIA OF CONTINENTAL F.A. BERG ARMY UNITS VALLEY FORGE PARK MICROFILM Continental Army at Valley Forge GEN GEORGE WASHINGTON Division: FIRST DIVISION MG CHARLES LEE SECOND DIVISION MG THOMAS MIFFLIN THIRD DIVISION MG MARQUES DE LAFAYETTE FOURTH DIVISION MG BARON DEKALB FIFTH DIVISION MG LORD STIRLING ARTILLERY BG HENRY KNOX CAVALRY BG CASIMIR PULASKI NJ BRIGADE BG WILLIAM MAXWELL Divisions were loosly organized during the encampment. Reorganization in May and JUNE set these Divisions as shown. KNOX'S ARTILLERY arrived Valley Forge JAN 1778 CAVALRY arrived Valley Forge DEC 1777 and left the same month. NJ BRIGADE departed Valley Forge in MAY and rejoined LEE'S FIRST DIVISION at MONMOUTH. Previous Division Commanders were; MG NATHANIEL GREENE, MG JOHN SULLIVAN, MG ALEXANDER MCDOUGEL MONTHLY STRENGTH REPORTS ALTERATIONS Month Fit For Duty Assigned Died Desert Disch Enlist DEC 12501 14892 88 129 25 74 JAN 7950 18197 0 0 0 0 FEB 6264 19264 209 147 925 240 MAR 5642 18268 399 181 261 193 APR 10826 19055 384 188 116 1279 MAY 13321 21802 374 227 170 1004 JUN 13751 22309 220 96 112 924 Totals: 70255 133787 1674 968 1609 3714 Ref: C.M. -

Business Center Boost Moved by Committee Last

t r ?- a . Schools offer new program for gifted A program for gifted children in grades three through live which w ill free, the youngsters from their textbooks was approved by the Board of £duca- *' tlon M ondayjight. Details on Page 4. A new collector will take your taxes Gerald Viturelle has been named the township's new tax collector, suc ceeding Alphonso j | Adinolfi. A change in state statute triggered Mr. Adinolfi's resignation from the post he had won in last November's elec- t tion. Story on Page 2. > , * Railroad station renovation decision due^ * A decision on the part of the Planning.Bbard is expected July 9 on the pro posal of Millburn Station Ltd. to renovate and enlarge the Essex Street .landmark. See Page 3. F IF E AND DRUMS — This fife and drum corps unit communities celebrated the bicentennial anniver Was but one of numerous contingents which march sary of the Battle of Springfield. Turn to Pages 8, 9 ed from ■Union to'Springfield to Millburn and then and 15 for additional photographic coverage of the back to Springfield Saturday afternoon, as the three celebration. Inside Classified........ Coming events. Editorial'......... Movies............ Obituaries....... Serving the township Social............ Sports ............. for 92 years OF MILLBURNAND SHOR T Thursday, June 26,1980 25 Cents per Copy, $12 per Year by Mail to Your D,oor Founded 1888, Vol. 92, No. 25 Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Town kills Business center boost Gero. Park tickets moved by Committee With the exception nf the dotting nf ftiv Y — iiillUteTilexl meeting which will be held members that merchants along Millburn Approximately 40 parking tickets given July 1. -

Lexington and Concord

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Lexington and Concord: A Legacy of Conflict Minute Man National Historical Park On April 19, 1775 ten years of political protest escalated as British soldiers clashed with “minute men” at Lexington, Concord, and along the a twenty-two- mile stretch of road that ran from Boston to Concord. The events that occurred along the Battle Road profoundly impacted the people of Massachusetts and soon grew into an American war for independence and self-government. This curriculum–based lesson plan is one Included in this lesson are several pages of in a thematic set on the American supporting material. To help identify these Revolution using lessons from other pages the following icons may be used: Massachusetts National Parks. Also are: To indicate a Primary Source page Boston National Historical Park To indicate a Secondary Source page To Indicate a Student handout Adams National Historical Park To indicate a Teacher resource Lesson Document Link on the page to the Salem Maritime National Historic Site document Lexington and Concord: A Legacy of Conflict Page 1 of 19 Minute Man National Historical Park National Park Service Minuteman National Historical Park commemorates the opening battles of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775. What had begun ten years earlier as political protest escalated as British soldiers clashed with colonial militia and “minute men” in a series of skirmishes at Lexington, Concord, and along the a twenty-two-mile stretch of road that ran from Boston to Concord. The events that occurred along the Battle Road profoundly impacted the people of Massachusetts and soon grew into an American war for independence and self-government. -

FORD MANSION Day

THE UPSTAIRS HALL As you enter the hall, notice the three Pennsylvania low-back Windsor chairs, circa 1750. These In this large hallway most of the winter's social activities are the earliest known American- took place. According to family tradition, the large camp chest style Windsor. to your left was left by Washington as a gift to Mrs. Ford. The folding cot would have been used by "Will," Washington's favorite servant, who as a matter of custom, slept close to the WASHINGTON'S CONFERENCE AND DINING ROOM General's bedroom. In this room the daily activities of Washington's staff were . Proceed to the next room on performed. Washington also used this room to meet with your left. officers and citizens. At 3 p.m. daily, Washington, Mrs. Washington, his staff, and guests began the main meal of the FORD MANSION day. At least three courses were served, and the meal took in THE AIDES' AND GUESTS' ROOM excess of two hours to consume. But much of that time was used to informally discuss military topics, such as supply, Most of Washington's aides slept in this room as evidenced by recruitment, and strategy for the spring campaign. the number of folding cots and traveling chests. However, when important guests came to the House, the aides moved Of special interest is the Chippendale desk thought to have into other quarters. In May of 1780, LaFayette stayed here as been here during the winter of 1779-80. Also observe the had the Spanish Ambassador Don Juan De Miralles. Chippendale mirror, a Ford family piece, with a Phoenix bird Unfortunately, De Miralles died while here as a guest of the arising from the top.