Learning Japanese-As-A-Foreign-Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study from the Perspectives of Shared Innovation

SUBGROUPING OF NISOIC (YI) LANGUAGES: A STUDY FROM THE PERSPECTIVES OF SHARED INNOVATION AND PHYLOGENETIC ESTIMATION by ZIWO QIU-FUYUAN LAMA Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2012 Copyright © by Ziwo Qiu-Fuyuan Lama 2012 All Rights Reserved To my parents: Qiumo Rico and Omu Woniemo Who have always wanted me to stay nearby, but they have also wished me to go my own way! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation could not have happened without the help of many people; I own much gratitude to these people and I would take this moment to express my heartfelt thanks to them. First, I wish to express my deep thanks to my supervisor, Professor Jerold A Edmondson, whose guidance, encouragement, and support from the beginning to the final page of this dissertation. His direction showed me the pathway of the writing of this dissertation, especially, while working on chapter of phylogenetic study of this dissertation, he pointed out the way to me. Secondly, I would like to thank my other committee members: Dr. Laurel Stvan, Dr. Michael Cahill, and Dr. David Silva. I wish to thank you very much for your contribution to finishing this dissertation. Your comments and encouragement were a great help. Third, I would like to thank my language informants and other people who helped me during my field trip to China in summer 2003, particularly ZHANF Jinzhi, SU Wenliang, PU Caihong, LI Weibing, KE Fu, ZHAO Hongying, ZHOU Decai, SHI Zhengdong, ZI Wenqing, and ZUO Jun. -

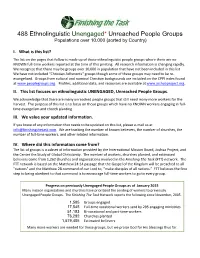

488 Ethnolinguistic Unengaged* Unreached People Groups Populations Over 10,000 (Sorted by Country)

XXX 488 Ethnolinguistic Unengaged* Unreached People Groups Populations over 10,000 (sorted by Country) I. What is this list? The list on the pages that follow is made up of those ethnolinguistic people groups where there are no KNOWN full-time workers reported at the time of this printing. All research information is changing rapidly. We recognize that there may be groups over 10,000 in population that have not been included in this list. We have not included "Christian Adherents" groups though some of these groups may need to be re- evangelized. Groups from cultural and nominal Christian backgrounds are included on the CPPI index found at www.peoplegroups.org. Profiles, additional data, and resources are available at www.joshuaproject.org. II. This list focuses on ethnolinguistic UNENGAGED, Unreached People Groups. We acknowledge that there are many unreached people groups that still need many more workers for the harvest. The purpose of this list is to focus on those groups which have no KNOWN workers engaging in full- time evangelism and church planting. III. We value your updated information. If you know of any information that needs to be updated on this list, please e-mail us at [email protected]. We are tracking the number of known believers, the number of churches, the number of full-time workers, and other related information. IV. Where did this information come from? The list of groups is a subset of information provided by the International Mission Board, Joshua Project, and the Center the Study of Global Christianity. The number of workers, churches planted, and estimated believers come from 1,262 churches and organizations involved in the Finishing The Task (FTT) network. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A Che in China A'ou in China Population: 43,000 Population: 2,800 World Popl: 43,000 World Popl: 2,800 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other People Cluster: Tai Main Language: Ache Main Language: Chinese, Mandarin Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A-Hmao in China Achang in China Population: 458,000 Population: 35,000 World Popl: 458,000 World Popl: 74,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Miao / Hmong People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other Main Language: Miao, Large Flowery Main Language: Achang Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Significantly reached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 75.0% Evangelicals: 7.0% Chr Adherents: 80.0% Chr Adherents: 7.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Wikipedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Achang, Husa in China Adi -

Sanie and Language Loss in China*

Sanie and language loss in China* DAVID BRADLEY Abstract Most of the many languages spoken by the large and widely distributed Yi nationality in China are endangered. One such is Sanie, spoken by about 8,000 people from a group of over 17,000 near Kunming in Yunnan. In surveying the area around Kuming, we located Sanie and a number of other undescribed and in most cases unreported endangered languages. Sanie is remarkable in that in some dialects it preserves velar plus /w/ clusters which have been simplified in all other closely related languages. Such a cluster is found in the group name; this gives us a clearer understanding of the original autonym for the Yi languages as a whole. Therefore, the new name Ngwi for this group of languages is proposed, with etymological justi- fications. Sanie also has a large range of internal di¤erences, suggesting that processes of change are speeded up during the process of language death. However it is shown to be a typical Eastern Yi language, like several of the other endangered languages spoken around Kunming including Sa- mataw and Samei. 1. The Yi nationality1 The Yi are one of China’s 55 minority nationalities, with a population of nearly eight million. They live in the southwest of the country; especially in Yunnan, southwestern Sichuan and western Guizhou Provinces, with a few also in western Guangxi. There are a couple of groups within Yi in south central Yunnan who also spread into northern Vietnam, and one into northeastern Laos. They are extremely heterogeneous but classified together by the Chinese. -

Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics No. 14: Tibeto-Bvrman Languages of the Himalayas

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series A-86 PAPERS IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN LINGUISTICS NO. 14: TIBETO-BVRMAN LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAS edited by David Bradley Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Bradley, D. editor. Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics No. 14:. A-86, vi + 232 (incl. 4 maps) pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-A86.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics specialises in publishing linguistic material relating to languages of East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Linguistic and anthropological manuscripts related to other areas, and to general theoretical issues, are also considered on a case by case basis. Manuscripts are published in one of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: M.D. Ross and D.T. Tryon (Managing Editors), T.E. Dutton, N.P. Himmelmann, A.K. Pawley EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University Universityof Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. K.J. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. -

Prayer Cards (431)

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Burmese in Australia Burmese in Bangladesh Population: 13,000 Population: 318,000 World Popl: 32,279,200 World Popl: 32,279,200 Total Countries: 19 Total Countries: 19 People Cluster: Burmese People Cluster: Burmese Main Language: Burmese Main Language: Burmese Main Religion: Buddhism Main Religion: Buddhism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.07% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.35% Chr Adherents: 1.62% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Kerry Olson "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Burmese in Myanmar (Burma) Burmese in Canada Population: 31,383,000 Population: 4,200 World Popl: 32,279,200 World Popl: 32,279,200 Total Countries: 19 Total Countries: 19 People Cluster: Burmese People Cluster: Burmese Main Language: Burmese Main Language: Burmese Main Religion: Buddhism Main Religion: Buddhism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.08% Evangelicals: 0.05% Chr Adherents: 0.35% Chr Adherents: 0.11% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Kerry Olson "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Burmese in Cambodia Burmese in Sri Lanka Population: 5,300 Population: 600 World Popl: 32,279,200 -

Dynamics of Language Contact in China: Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Variation in Yunnan

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa PhD Dissertation Dynamics of Language Contact in China: Ethnolinguistic Diversity and Variation in Yunnan Katie B. Gao 2017 A dissertation submitted to the UHM Graduate Division in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Dissertation committee: Katie Drager, Chairperson Andrea Berez-Kroeker David Bradley Lyle Campbell Everett Wingert 献给纾含和她的家人 For Shuhan and her family Acknowledgments This dissertation is by no means a product of just one person but was made possible by generous funding agencies, patient mentors and research partners, and encouraging friends and family. I am grateful to the following groups who fnancially supported the research that led to this dissertation: the National Science Foundation, for feld research to supplement the Catalogue of Endangered Languages; the Bilinski Educational Foundation, for feld research and proposal development; the UH Mānoa College of Arts and Sciences for feld research; the UH Mānoa College of Languages, Linguistics and Literature, for dissertation development; the UH Mānoa Graduate Student Organization, for conference funding; and the Department of Linguistics for making my graduate student career fnancially feasible. I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Katie Drager, for her practical guidance on papers, professional development, and life in general. I am a better thinker and writer because of your whys and so whats over the years. To the rest of my wonderful committee: Andrea, thank you for being a steady support with your always-sound advice throughout my time at UH ; Lyle, thank you for your willingness to help at any time with any question or issue from theory to funding; David, thank you for being a source of information and encouragement from the beginning of my interest to pursue research in Yunnan; and Ev, thank you for sharing your love of cartographic design through your teaching and stories, you’re a main reason why there are maps in my dissertation. -

New Developments in the Quantitative Study of Languages Book of Abstracts

New Developments in the Quantitative Study of Languages Book of abstracts Organized by the Linguistic Association of Finland http://www.linguistics.fi 28–29 August 2015 House of Science and Letters (“Tieteiden talo”) Kirkkokatu 6, 00170 Helsinki http://www.linguistics.fi/quantling-2015/ Acknowledgements Financial support from the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies is gratefully acknowl- edged. Contents I. Keynotes6 Cysouw, Michael: Advances in computer-assisted quantitative historical reconstruc- tion.......................................7 Gries, Stefan Th.: More and better regression analyses: what they can do for us and how.......................................9 II. Section papers 10 Aedmaa, Eleri: Extraction of Estonian particle verbs from text corpus using statis- tical methods.................................. 11 Blasi, Damian: New methods for causal inference in the language sciences..... 13 Dahl, Östen: Investigating grammtical space in a parallel corpus.......... 15 Dubossarsky, Haim, et al.: Using computational tools to identify semantic change and its causes.................................. 16 Grafmiller, Jason: Exploring new methods for analyzing language change..... 19 Härme, Juho: Clause-initial adverbials of time in Finnish and Russian: a quantita- tive approach.................................. 21 Holman, Eric W. and Søren Wichmann: New evidence from linguistic phylogenetics supports phyletic gradualism.......................... 23 Hörberg, Thomas: Incremental syntactic prediction in the comprehension of Swedish -

Word Order of Numeral Classifiers and Numeral Bases: Harmonization by Multiplication

Word Order of Numeral Classifiers and Numeral Bases: Harmonization by Multiplication Abstract In a numeral classifier language, a sortal classifier (C) or a mensural classifier (M) is needed when a noun is quantified by a numeral (Num). Greenberg (1990b, p. 185) first observes that cross-linguistically Num and C/M are adjacent, either in a [Num C/M] order or [C/M Num]. Likewise, in a complex numeral with a multiplicative composition, the base may follow the multiplier as in [n × base], e.g., san-bai ‘three hundred’ in Standard Mandarin. However, the base may precede the multiplier, thus [base × n], which is also attested. Greenberg (1990a, p. 293) further observes that [n × base] numerals appear with a [Num C/M] alignment and [base × n] numerals with [C/M Num]; base and C/M thus seem to harmonize in word order. This paper first motivates the base-C/M harmonization via the multiplicative theory of classifiers (Her, 2012a, 2017a), and verifies it empirically within six language groups in the world’s foremost hotbed of classifier languages: Sinitic, Miao-Yao, Austro-Asiatic, Tai-Kadai, Tibeto-Burman, and Indo-Aryan. Our survey further reveals two interesting facts: base-initial ([base × n]) and C/M-initial ([C/M Num]) orders exist only in Tibeto-Burman (TB) within our dataset and so are the few scarce violations to the base-C/M harmonization. We offer an explanation based on Proto-TB’s base-initial numerals and language contact with neighboring base-final, C/M-final languages. Keywords: classifier, multiplication, numeral base, harmonization 1. Introduction In a numeral classifier language, a sortal classifier (C) or a mensural classifier (M) is required when a noun (N) is quantified by a numeral (Num) (e.g., Aikhenvald, 2000; Allan, 1977; Tai & Wang, 1990). -

The Top Unengaged Unreached People Groups of East Asia

UUPG THE TOP UNENGAGED UNREACHED PEOPLE GROUPS OF EAST ASIA vol. 4 “A VAST MULTITUDE FROM EVERY NATION, TRIBE, PEOPLE, AND LANGUAGE ...” INTRODUCTION 04 ALXA MONGOL 06 AZHE 08 BAONUO (BAIKU) 09 SOUTHERN DALI LOLO (ENIPU) 10 DIGAO 11 DZALAKHA 12 E PEOPLE 13 ERSU 14 GA MONG 15 THE HUI DIASPORA 16 JONE TIBETAN 18 LABA 19 LAWU 20 LESU 22 LIMIN 23 LINGHUA 24 WESTERN LUOLUOPO 25 LUOWU 26 LUPANSHUI MIAO 27 MASHAN MIAO 28 MJUNIANG 29 MO 30 MONGOLS OF HENAN COUNTY 31 NGHARI TIBETAN 32 PINGDI YAO 34 SHUIXI NOSU 35 SICHUAN MONGOL 36 TUSU 37 WALANGCHUNG 38 EASTERN XIANGXI MIAO 40 WESTERN XIBE 42 XIJIMA 43 XINPING LALU 44 YANGHUANG 46 YOUNUO 47 EAST ASIA MAP 48 MORE UUPGS 50 ... THERE IS NO HOPE WE CAN FINISH THE TASK AMONG UNREACHED PEOPLES UNLESS WE ARE FILLED WITH THE SPIRIT; CARRIED ALONG FROM DAY TO DAY, MOMENT BY MOMENT ... Greetings in the glorious and awesome name sake of the gospel. However, there is no hope of Jesus Christ! There is a beautiful picture we can finish the task among unreached in Revelation 7:9-10 (HCSB), which says, peoples unless we are filled with the Spirit; “After this I looked, and there was a vast carried along from day to day, moment by multitude from every nation, tribe, people, moment, and from enterprise to enterprise and language, which no one could number, with the wonder-working power of the Spirit standing before the throne and before the of God. Lamb. They were robed in white with palm branches in their hands. -

Assessment of Language Endangerment in the Kinga Speech Community: Makete District - Tanzania

The University of Dodoma University of Dodoma Institutional Repository http://repository.udom.ac.tz Humanities Master Dissertations 2018 Assessment of language endangerment in the Kinga speech community: Makete district - Tanzania Sanga, Edison The University of Dodoma Sanga, E. (2018). Assessment of language endangerment in the Kinga speech community: Makete district - Tanzania (Master's dissertation). The University of Dodoma, Dodoma. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12661/889 Downloaded from UDOM Institutional Repository at The University of Dodoma, an open access institutional repository. ASSESSMENT OF LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT IN THE KINGA SPEECH COMMUNITY: MAKETE DISTRICT - TANZANIA EDISON SANGA MASTER OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS THE UNIVERSITY OF DODOMA OCTOBER, 2018 1 ASSESSMENT OF LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT IN THE KINGA SPEECH COMMUNITY: MAKETE DISTRICT - TANZANIA BY EDISON SANGA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS THE UNIVERSITY OF DODOMA OCTOBER, 2018 i DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT I Edison Sanga, declare that this dissertation is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any other University for a similar or any other degree award. Signature………………………………………………….. No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior or written permission of the author or the University of Dodoma. If transformed for publication in any other format shall be acknowledged that, this work has been submitted for degree award at the University of Dodoma. i CERTIFICATION The undersigned certifies that she has read and hereby recommends for acceptance by the University of Dodoma dissertation entitled Assessment of Language Endangerment in the Kinga Speech Community: Makete District Tanzania in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics of the University of Dodoma. -

Word Order of Numeral Classifiers and Numeral Bases: Harmonization by Multiplication

Word Order of Numeral Classifiers and Numeral Bases: Harmonization by Multiplication Abstract In a numeral classifier language, a sortal classifier (C) or a mensural classifier (M) is needed when a noun is quantified by a numeral (Num). Num and C/M are adjacent cross-linguistically, either in a [Num C/M] order or [C/M Num]. Likewise, in a complex numeral with a multiplicative composition, the base may follow the multiplier as in [n × base], e.g., san-bai ‘three hundred’ in Mandarin. However, the base may also precede the multiplier in some languages, thus [base × n]. Interestingly, base and C/M seem to harmonize in word order, i.e., [n × base] numerals appear with a [Num C/M] alignment, and [base × n] numerals, with [C/M Num]. This paper follows up on the explanation of the base-C/M harmonization based on the multiplicative theory of classifiers and verifies it empirically within six language groups in the world’s foremost hotbed of classifier languages: Sinitic, Miao-Yao, Austro-Asiatic, Tai-Kadai, Tibeto-Burman, and Indo-Aryan. Our survey further reveals two interesting facts: base-initial ([base × n]) and C/M-initial ([C/M Num]) orders exist only in Tibeto-Burman (TB) within our dataset. Moreover, the few scarce violations to the base-C/M harmonization are also all in TB and are mostly languages having maintained their original base-initial numerals but borrowed from their base-final and C/M-final neighbors. We thus offer an explanation based on Proto-TB’s base-initial numerals and language contact with neighboring base-final, C/M-final languages.