20 Socrates in Arabic Philosophy ILAI ALON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf 589.55 K

ORIGINAL ARTICLE The Sabians of Harran’s Impact on the Islamic Medicine: From Third Century to the Fifth AH 97 Abstract Reza Afsharisadr1 Various factors have been involved in the growth and flourishing of Mohammadali Chelongar2 Medicine as one of the most important sciences in Islamic civilization. Mostafa Pirmoradian3 The transfer of the Chaldean and Greek Medicine tradition to Islamic 1- PhD student, department of history, Medicine by the Sabians of Harran can be regarded as an essential ele- Faculty of Literature and Humanity, Uni- ment in its development in Islamic civilization. The present study seeks vercity of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran 2- Professor, department of history, Fac- to investigate the influence of Sabians of Harran on Islamic Medicine ulty of Literature and Humanity, Univer- and explore the areas which provided the grounds for the Sabians of city of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran 3- Assistant Professor, department of his- Harranon Islamic Medicine. It is also an attempt to find out how they tory, Faculty of Literature and Humanity, influenced the progress of Medicine in Islamic civilization. A descrip- Univercity of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran tive-analytical method was adopted on early sources and later studies to answer the research questions. The research results indicated that in the Correspondence: Mohammadali Chelongar first place, factors such as the Chaldean Medicine tradition, the culture Professor, department of history, Faculty and Medicine of Greek, the transfer of the Harran Scoole Medicine in of Literature and Humanity, Univercity Baghdad were the causes of the flourishing of Islamic Medicine. Then, of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran [email protected] the caliphs and other officials’ treatment through doctors’ examinations had contribution to the establishment and administration of hospitals, while influencing the process of medical sciences in Baghdad and other Citation: parts of the Muslim world, thereby helping the development of this sci- Afsharisadr R, Chelongar M, ence in Islamic civilization. -

Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı Ve Osmanlı Devleti

Aysoy / “Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı ve Osmanlı Devleti “Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı ve Osmanlı Devleti Mehmet Aysoy* Öz: Bilim tarihinde modern bilimin ortaya çıkışı kadar yayılması da eş değer önemdedir. Bilim tarihinde “Bilim devrimi” yaklaşımı astronomiyi nirengi noktası yapmakta ve modernliği bu merkezden kavramlaştırmaktadır. Astronomide ortaya çıkan gelişmelerin Batı-dışına yansıması aynı etkiyi vermezken diğer bilim alanlarındaki gelişmelerin yansımaları belirleyici olmuştur, ki tıp bu alanların başında gelmektedir, erken modernlik döne- minde gelişimi tartışılabilir boyutlarda olmasına rağmen Batı-dışında özelde Osmanlıda karşılık bulmuştur. Bu durumun değerlendirilebilmesi için modern bilimin ortaya çıkması ve yayılmasına dair daha ucu açık yak- laşımların geliştirilmesi gerekmektedir. Bu çalışmada bilim devrimi kavramı yanında tıp alanında gerçekleşen çalışmalar, İslam/Osmanlı tıp düşüncesinin konu edilebilmesi açısından değerlendirilmiştir. Konunun modernlik açısından değerlendirilmesi, modernliğin tarihine dair dönemlerin içinde değerlendirilmesini gerektirmektedir ve bu anlamda ‘erken modernlik’ bilim devrimi olarak kayıtlanan döneme sosyolojik bir bağlam kazandırır. Erken modernlik geleneğin kavramsal bir çözümleme aracı olarak işlevsel olduğu bir dönemdir. Modernlik bir devrim ekseninde değil de bir süreç içerisinde değerlendirildiğinde gelenek ve geleneğin değişimi temel bağ- lamı ifade eder, bu doğrultuda da yeni kavramlaştırmalar gerekli olmaktadır. Bu çalışmada ‘arayüz’ kavramına başvurulmuştur ve geleneğin değişimi ‘arayüz’ -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83824-5 - The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 4 Islamic Cultures and Societies to the End of the Eighteenth Century Edited by Robert Irwin Index More information Index NOTES 1. The Arabic definite article (al-), the transliteration symbols for the Arabic letters hamza (p) and qayn (q), and distinctions between different letters transliterated by the same Latin character (e.g. d and d.) are ignored for purposes of alphabetisation. 2. In the case of personal names sharing the same first element, rulers are listed first, then individuals with patronymics, then any others. 3. Locators in italics denote illustrations. Aba¯d.iyya see Iba¯d.iyya coinage 334, 335, 688–690, 689 qAbba¯da¯n 65 Dome of the Rock built by 690 qAbba¯s I, Sha¯h 120, 266, 273, 281, 300–301, 630 qAbd al-Qa¯dir al-Baghda¯d¯ı 411 qAbba¯s II, Sha¯h 266 qAbd al-Rapu¯f al-Singkil¯ı 103, 518 al-qAbba¯s ibn qAbd al-Mut.t.alib 109, 112 qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n II ibn al-H. akam, caliph of qAbba¯s ibn Firna¯s 592 Cordoba 592, 736 qAbba¯s ibn Na¯s.ih. 592 qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n III, caliph of Cordoba qAbba¯sids 621, 663 qAbba¯sid revolution 30, 228–229, 447; and qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n al-S.u¯f¯ı 599–600, 622 religion 110, 111–112, 228; and qAbd al-Razza¯q Samarqand¯ı 455 translation movement 566, qAbd al-Wa¯h.id ibn Zayd 65 567–568 qAbda¯n 123–124 foundation of dynasty 30, 31, 229 qAbdu¯n ibn Makhlad 397 Mongols destroy Baghdad caliphate 30, 49 abjad system 456 rump caliphate in Cairo 49, 56, 246, 251, ablaq architectural decoration 702 253–254 abna¯ p al-dawla 229 see also individual caliphs and individual topics Abraham 19, 27, 36, 125, 225 qAbba¯siyya see Ha¯shimiyya abrogation, theory of 165 qAbd Alla¯h ibn al-qAbba¯s 111, 225 A¯ bru¯, Sha¯h Muba¯rak 436 qAbd Alla¯h al-Aft.ah. -

Translators Role During Transmissing Process Of

IJISET - International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, Vol. 3 Issue 3, March 2016. www.ijiset.com ISSN 2348 – 7968 The Intermediary Role of The Arabs During The Middle Ages In The Transmission Of Ancient Scientific Knowledge To Europe Prof. Dr. Luisa María Arvide Cambra Department of Philology.University of Almería. Almería. Spain Abstract One of the most important roles of the Islamic civilization is that of having transmitted the Ancient 2.Translators from Greek into Arabic culture to the European Renaissance through the process of translation into Arabic of scientific There were two great schools of translation knowledge of Antiquity, i.e. the Sanskrit, the Persian, from Greek into Arabic: that of the Christian the Syriac, the Coptic and, over all, the Greek, during th th Nestorians of Syria and that of the Sabeans of the 8 and 9 centuries. Later, this knowledge was Harran [4]. enriched by the Arabs and was transferred to Western Europe thanks to the Latin translations made in the 12th and 13th centuries. This paper analyzes this 2.1.The Nestorians process with special reference to the work done by - Abu Yahyà Sa‘id Ibn Al-Bitriq (d. circa 796- the most prominent translators. 806). He was one of the first translators from Keywords: Medieval Arabic Science, Arabian Greek into Arabic. To him it is attributed the Medicine, Scientific Knowledge in Medieval Islam, translation of Hippocrates and the best writings Transmission of Scientific Knowledge in the Middle by Galen as well as Ptolomy´s Quadripartitum. Ages, Medieval Translators - Abu Zakariya’ Yuhanna Ibn Masawayh (777- 857), a pupil of Jibril Ibn Bakhtishu’. -

Lat. Tacuinum Sanitatis) U

Innovación en el discurso científico medieval a través del JOSÉ ANTONIO GONZÁLEZ MARRERO Inst. de Estudios Medievales y Renacentistas Taqwīm Al-Ṣiḥḥa de Ibn Buṭlān (Lat. Tacuinum Sanitatis) U. de La Laguna, Tenerife, España Innovation in Medieval Scientific Discourse through Ibn Buṭlān’s Taqwīm 1 Al-Ṣiḥḥa (Lat. Tacuinum Sanitatis) Profesor titular de Filología Latina de la Universidad de La Laguna. Desde 1991 centra su actividad docente en la enseñanza de la Lengua y Literatura Latinas. Desarrolla Resumen su investigación en el Instituto Universitario El Tacuinum sanitatis, obra del persa Ibn Buṭlān (siglo 5 H. / XI J. C.), sigue los contenidos de de Estudios Medievales y Renacentistas los tratados hipocráticos de los siglos V y IV a. C. Estos textos dan importancia a la dieta, (IEMyR). Ha publicado unos 60 trabajos de entendida como el equilibrio del hombre con su entorno y de los alimentos con los ejercicios investigación y ha participado en congresos físicos. En su origen árabe, el contenido del Tacuinum sanitatis fue dispuesto con un innova- nacionales e internacionales con más de 40 dor uso de tablas sinópticas, usadas con anterioridad en textos de tema astronómico. En el comunicaciones y conferencias. presente artículo nos ocupamos del Tacuinum sanitatis de Ibn Buṭlān como parte relevante de la interrelación entre el legado árabe y el desarrollo del galenismo en Europa, particularmente en la aceptación de una medicina práctica y preventiva que persigue el equilibrio humoral como garantía de buena salud. Particularmente estudiamos el contenido de la versión latina del Tacuinum sanitatis de Ibn Buṭlān conservada en el ms. lat. -

Occidental Diffusion of Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus) 500–1300 CE: Two Routes to Europe

Annals of Botany Page 1 of 10 doi:10.1093/aob/mcr281, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Occidental diffusion of cucumber (Cucumis sativus) 500–1300 CE: two routes to Europe Harry S. Paris1,*, Marie-Christine Daunay2 and Jules Janick3 1Department of Vegetable Crops & Plant Genetics, Agricultural Research Organization, Newe Ya‘ar Research Center, PO Box 1021, Ramat Yishay 30-095, Israel, 2INRA, UR1052 Unite´ de Ge´ne´tique et d’Ame´lioration des Fruits et Legumes, Montfavet, Downloaded from France and 3Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University, 625 Agriculture Mall Drive, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2010, USA * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 16 June 2011 Returned for revision: 5 September 2011 Accepted: 30 September 2011 http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/ † Background The cucumber, Cucumis sativus, is one of the most widely consumed fruit vegetables the world over. The history of its dispersal to the Occident from its centre of origin, the Indian subcontinent, has been in- correctly understood for some time, due to the confusion of cucumbers with vegetable melons. Iconographic and literary evidence has shown that cucumber was absent in Roman times, up to 500 CE, but present in Europe by late medieval times, 1300. The objective of the present investigation was to determine more accurately when the cucumber arrived in Europe and by what route. † Findings and Conclusions The evidence for the movement of C. sativus westward is entirely lexicographical until the 10th century. Syriac, Persian and Byzantine Greek sources suggest the presence of cucumbers, to the at The Agricultural Research Organization of Israel (Volcani) on November 20, 2011 east and north-east of the Mediterranean Sea (modern Iran, Iraq and Turkey), by the 6th or 7th century. -

Pharmacopoeia) in Greeco-Arabian Era : a Historical and Regulatory Perspective Mohd Akhtar Ali1, Hamiduddin2

International Journal of Human and Health Sciences Vol. 05 No. 04 October’21 Review Article Qarābādhīn (Pharmacopoeia) in Greeco-Arabian era : A Historical and Regulatory Perspective Mohd Akhtar Ali1, Hamiduddin2 Abstract Qarābādhīn can be termed as pharmacopoeia, contains compiled form of compound formulations or recipes. Importance of Qarābādhīn gradually increased and acquired an imperative status. The history of Qarābādhīn starts from Chiron, Aesculapius, Hippocrates, Dioscorides and Galen in Greco-Roman era. Many of early and medieval Islamic and Arab physicians play vital role and immense original contribution in this discipline and authored important and essential Qarābādhīn with systemic and scientific approaches. Although some of them could not reach the present day, many of the manuscripts can be found in various libraries across the world. Since the Arab Caliphates appreciated and patronized the fields of medicine acquired from Greeks and worked for its development, this period also known as “Greco-Arabic era”. In this work the evaluation of Qarābādhīn (particularly written in Arabic or Greek language) was done in historical and regulatory perspective particularly in Greek era and later on in Medieval Islamic era. The findings of the review indicate the importance and regulatory status of Qarābādhīn and provide information about it. It can be helpful to explore Qarābādhīn and related publications of Greek and Medieval Islamic Arabic period, which gives foundations for the present-day pharmacopeias. Since these documents also take into account ethical considerations, its utility in the fields of medicine and medical ethics should be investigated. Keywords: Qarābādhīn, Pharmacopoeia, Greek, Medieval Islamic Medicine, Kūnnāsh, Unani Medicine. International Journal of Human and Health Sciences Vol. -

International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine

Article ID: WMC003549 ISSN 2046-1690 International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages Corresponding Author: Dr. Mohammad Amin Rodini, Faculty Member, Department of Basice Science , Nikshahr Branch , Islamic Azad university,Nikashr - Iran (Islamic Republic of) Submitting Author: Journal Admin International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine Article ID: WMC003549 Article Type: Review articles Submitted on:02-Jul-2012, 04:25:28 AM GMT Published on: 07-Jul-2012, 07:45:15 AM GMT Article URL: http://www.webmedcentral.com/article_view/3549 Subject Categories:MEDICAL EDUCATION Keywords:Medical care , Islam , Middle Ages ,Bimaristan (Hospital). How to cite the article:Rodini M. Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages . WebmedCentral:International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine 2012;3(7):WMC003549 Copyright: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License(CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine is an associate journal of Webmedcentral. WebmedCentral: International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine > Review articles Page 1 of 14 WMC003549 Downloaded from http://www.webmedcentral.com on 07-Jul-2012, 07:45:15 AM Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages Author(s): Rodini M Abstract Messenger (s.a.w) reiterated: “Pray for good health.” The man asked again: Then what? God’s Messenger (s.a.w) replied again: “Pray for good health and well being in this world and in the hereafter.”[3] The present paper is an endeavor to study some issues related to medical care and hospital during the Secondly, since healthy is the most prized, precious, Middle Ages. -

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin Translated by Liadain Sherrard with the assistance of Philip Sherrard KEGAN PAUL INTERNATIONAL London and New York in association with ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS for THE INSTITUTE OF ISMAILI STUDIES London The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London The Institute of Ismaili Studies was established in 1977 with the object of promoting scholarship and learning on Islam, in the historical as well as contemporary context, and a better understanding of its relationship with other societies and faiths. The Institute's programmes encourage a perspective which is not confined to the theological and religious heritage of Islam, but seek to explore the relationship of religious ideas to broader dimensions of society and culture. They thus encourage an inter-disciplinary approach to the materials of Islamic history and thought. Particular attention is also given to issues of modernity that arise as Muslims seek to relate their heritage to the contemporary situation. Within the Islamic tradition, the Institute's programmes seek to promote research on those areas which have had relatively lesser attention devoted to them in secondary scholarship to date. These include the intellectual and literary expressions of Shi'ism in general, and Ismailism in particular. In the context of Islamic societies, the Institute's programmes are informed by the full range and diversity of cultures in which Islam is practised today, from the Middle East, Southern and Central Asia and Africa to the industrialized societies of the West, thus taking into consideration the variety of contexts which shape the ideals, beliefs and practices of the faith. The publications facilitated by the Institute will fall into several distinct categories: 1 Occasional papers or essays addressing broad themes of the relationship between religion and society in the historical as well as modern context, with special reference to Islam, but encompassing, where appropriate, other faiths and cultures. -

JISHIM 2017-2018-2019.Indb

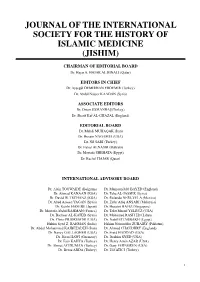

JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) CHAIRMAN OF EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Hajar A. HAJAR AL BINALI (Qatar) EDITORS IN CHIEF Dr.'U$\üHJLLO'(0,5+$1(5'(0,5 7XUNH\ Ayşegül DEMIRHAN ERDEMIR (Turkey) 'U$EGXO1DVVHU.$$'$1 6\ULD ASSOCIATE EDITORS 'U2]WDQ860$1%$û 7XUNH\ 'U6KDULI.DI$/*+$=$/ (QJODQG EDITORIAL BOARD 'U0DKGL08+$4$. ,UDQ 'U+XVDLQ1$*$0,$ 86$ 'U1LO6$5, 7XUNH\ 'U)DLVDO$/1$6,5 %DKUDLQ 'U0RVWDID6+(+$7$ (J\SW 'U5DFKHO+$-$5 4DWDU INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Alan TOUWAIDE (Belgum) Dr. Mamoun MO BAYED (England) Dr. Ahmad KANAAN (KSA) Dr. Taha AL-JASSER (Syra) Dr. Davd W. TSCHANZ (KSA) Dr. Rolando NERI-VELA (Mexco) Dr. Abed Ameen YAGAN (Syra) Dr. Zafar Afaq ANSARI (Malaysa) Dr. Kesh HASEBE (Japan) Dr. Husan HAFIZ (Sngapore) Dr. Mustafa Abdul RAHMAN (France) Dr. Talat Masud YELBUZ (USA) Dr. Bacheer AL-KATEB (Syra) Dr. Mohamed RASH ED (Lbya) Dr. Plno PRIORESCHI (USA) Dr. Nabl El TABBAKH (Egypt) Hakm Syed Z. RAHMAN (Inda) Hakm Namuddn ZUBAIRY (Pakstan) Dr. Abdul Mohammed KAJBFZADEH (Iran) Dr. Ahmad CHAUDHRY (England) Dr. Nancy GALLAGHER (USA) Dr. Frad HADDAD (USA) Dr. Rem HAWI (Germany) Dr. Ibrahm SYED (USA) Dr. Esn KAHYA (Turkey) Dr. Henry Amn AZAR (USA) Dr. Ahmet ACIDUMAN (Turkey) Dr. Gary FERNGREN (USA) Dr. Berna ARDA (Turkey) Dr. Elf ATICI (Turkey) I JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) Perods: Journal of ISHIM s publshed twce a year n Aprl and October. Address Changes: The publsher must be nformed at least 15 days before the publcaton date. All artcles, fgures, photos and tables n ths journal can not be reproduced, stored or transmtted n any form or by any means wthout the pror wrtten permsson of the publsher. -

Music Therapy and Mental Health Mental Health Care and Bimaristans in the Medical History of Islamic Societies

Rüdiger Lohlker (Vienna University) Music Therapy and Mental Health Mental Health Care and Bimaristans in the Medical History of Islamic Societies Even recent studies on the histories of hospitals only have few pages on Islamic hospitals.1 Thus, it is necessary to turn to a thorough study of Islamic hospitals as an important element of a global history of hospitals and health care. There are other names for hospitals in Islamic times, but this study will use the term bīmāristān to identify these institutions. Our focus will be on mental health and bīmāristāns another field still underresearched.2 Recent studies claim that going beyond the classical studies of ideas of medicine and leaving the old paradigms of Islamic exceptionalism behind, would allow for an integration of the study of medicine in Islamic societies into the field of science studies3 and for a better understanding of the institutional contexts of medical practice.4 Understanding the history of Islamic hospitals means turning to pre-Islamic times.5 We could turn to pre-Islamic Arabia6, but more important may be the Eastern part of what was to be the Islamic world. Thus, we will be able to look into the institutional contexts of Islamic medicine7 – and especially its aspects related to mental health.8 1 In numbers: four pages, thus, excluding Islamic institutions from a general history of hospitals (Risse 1999). 2 Thanks to Margareta Wetchy for her valuable comments. Thanks also to the organizers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences of the Maimonides Lectures 2019 in the Austrian city of Krems who gave the opportunity to present a first version of these ideas. -

History of Islamic Science

History of Islamic Science George Sarton‟s Tribute to Muslim Scientists in the “Introduction to the History of Science,” ”It will suffice here to evoke a few glorious names without contemporary equivalents in the West: Jabir ibn Haiyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Fargani, Al-Razi, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Battani, Hunain ibn Ishaq, al-Farabi, Ibrahim ibn Sinan, al-Masudi, al-Tabari, Abul Wafa, ‘Ali ibn Abbas, Abul Qasim, Ibn al-Jazzar, al-Biruni, Ibn Sina, Ibn Yunus, al-Kashi, Ibn al-Haitham, ‘Ali Ibn ‘Isa al- Ghazali, al-zarqab,Omar Khayyam. A magnificent array of names which it would not be difficult to extend. If anyone tells you that the Middle Ages were scientifically sterile, just quote these men to him, all of whom flourished within a short period, 750 to 1100 A.D.” Preface On 8 June, A.D. 632, the Prophet Mohammed (Peace and Prayers be upon Him) died, having accomplished the marvelous task of uniting the tribes of Arabia into a homogeneous and powerful nation. In the interval, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, the whole North Africa, Gibraltar and Spain had been submitted to the Islamic State, and a new civilization had been established. The Arabs quickly assimilated the culture and knowledge of the peoples they ruled, while the latter in turn - Persians, Syrians, Copts, Berbers, and others - adopted the Arabic language. The nationality of the Muslim thus became submerged, and the term Arab acquired a linguistic sense rather than a strictly ethnological one. As soon as Islamic state had been established, the Arabs began to encourage learning of all kinds.