Pdf 589.55 K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı Ve Osmanlı Devleti

Aysoy / “Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı ve Osmanlı Devleti “Bilim Devrimi” Kavramı ve Osmanlı Devleti Mehmet Aysoy* Öz: Bilim tarihinde modern bilimin ortaya çıkışı kadar yayılması da eş değer önemdedir. Bilim tarihinde “Bilim devrimi” yaklaşımı astronomiyi nirengi noktası yapmakta ve modernliği bu merkezden kavramlaştırmaktadır. Astronomide ortaya çıkan gelişmelerin Batı-dışına yansıması aynı etkiyi vermezken diğer bilim alanlarındaki gelişmelerin yansımaları belirleyici olmuştur, ki tıp bu alanların başında gelmektedir, erken modernlik döne- minde gelişimi tartışılabilir boyutlarda olmasına rağmen Batı-dışında özelde Osmanlıda karşılık bulmuştur. Bu durumun değerlendirilebilmesi için modern bilimin ortaya çıkması ve yayılmasına dair daha ucu açık yak- laşımların geliştirilmesi gerekmektedir. Bu çalışmada bilim devrimi kavramı yanında tıp alanında gerçekleşen çalışmalar, İslam/Osmanlı tıp düşüncesinin konu edilebilmesi açısından değerlendirilmiştir. Konunun modernlik açısından değerlendirilmesi, modernliğin tarihine dair dönemlerin içinde değerlendirilmesini gerektirmektedir ve bu anlamda ‘erken modernlik’ bilim devrimi olarak kayıtlanan döneme sosyolojik bir bağlam kazandırır. Erken modernlik geleneğin kavramsal bir çözümleme aracı olarak işlevsel olduğu bir dönemdir. Modernlik bir devrim ekseninde değil de bir süreç içerisinde değerlendirildiğinde gelenek ve geleneğin değişimi temel bağ- lamı ifade eder, bu doğrultuda da yeni kavramlaştırmalar gerekli olmaktadır. Bu çalışmada ‘arayüz’ kavramına başvurulmuştur ve geleneğin değişimi ‘arayüz’ -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83824-5 - The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 4 Islamic Cultures and Societies to the End of the Eighteenth Century Edited by Robert Irwin Index More information Index NOTES 1. The Arabic definite article (al-), the transliteration symbols for the Arabic letters hamza (p) and qayn (q), and distinctions between different letters transliterated by the same Latin character (e.g. d and d.) are ignored for purposes of alphabetisation. 2. In the case of personal names sharing the same first element, rulers are listed first, then individuals with patronymics, then any others. 3. Locators in italics denote illustrations. Aba¯d.iyya see Iba¯d.iyya coinage 334, 335, 688–690, 689 qAbba¯da¯n 65 Dome of the Rock built by 690 qAbba¯s I, Sha¯h 120, 266, 273, 281, 300–301, 630 qAbd al-Qa¯dir al-Baghda¯d¯ı 411 qAbba¯s II, Sha¯h 266 qAbd al-Rapu¯f al-Singkil¯ı 103, 518 al-qAbba¯s ibn qAbd al-Mut.t.alib 109, 112 qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n II ibn al-H. akam, caliph of qAbba¯s ibn Firna¯s 592 Cordoba 592, 736 qAbba¯s ibn Na¯s.ih. 592 qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n III, caliph of Cordoba qAbba¯sids 621, 663 qAbba¯sid revolution 30, 228–229, 447; and qAbd al-Rah.ma¯n al-S.u¯f¯ı 599–600, 622 religion 110, 111–112, 228; and qAbd al-Razza¯q Samarqand¯ı 455 translation movement 566, qAbd al-Wa¯h.id ibn Zayd 65 567–568 qAbda¯n 123–124 foundation of dynasty 30, 31, 229 qAbdu¯n ibn Makhlad 397 Mongols destroy Baghdad caliphate 30, 49 abjad system 456 rump caliphate in Cairo 49, 56, 246, 251, ablaq architectural decoration 702 253–254 abna¯ p al-dawla 229 see also individual caliphs and individual topics Abraham 19, 27, 36, 125, 225 qAbba¯siyya see Ha¯shimiyya abrogation, theory of 165 qAbd Alla¯h ibn al-qAbba¯s 111, 225 A¯ bru¯, Sha¯h Muba¯rak 436 qAbd Alla¯h al-Aft.ah. -

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin Translated by Liadain Sherrard with the assistance of Philip Sherrard KEGAN PAUL INTERNATIONAL London and New York in association with ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS for THE INSTITUTE OF ISMAILI STUDIES London The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London The Institute of Ismaili Studies was established in 1977 with the object of promoting scholarship and learning on Islam, in the historical as well as contemporary context, and a better understanding of its relationship with other societies and faiths. The Institute's programmes encourage a perspective which is not confined to the theological and religious heritage of Islam, but seek to explore the relationship of religious ideas to broader dimensions of society and culture. They thus encourage an inter-disciplinary approach to the materials of Islamic history and thought. Particular attention is also given to issues of modernity that arise as Muslims seek to relate their heritage to the contemporary situation. Within the Islamic tradition, the Institute's programmes seek to promote research on those areas which have had relatively lesser attention devoted to them in secondary scholarship to date. These include the intellectual and literary expressions of Shi'ism in general, and Ismailism in particular. In the context of Islamic societies, the Institute's programmes are informed by the full range and diversity of cultures in which Islam is practised today, from the Middle East, Southern and Central Asia and Africa to the industrialized societies of the West, thus taking into consideration the variety of contexts which shape the ideals, beliefs and practices of the faith. The publications facilitated by the Institute will fall into several distinct categories: 1 Occasional papers or essays addressing broad themes of the relationship between religion and society in the historical as well as modern context, with special reference to Islam, but encompassing, where appropriate, other faiths and cultures. -

JISHIM 2017-2018-2019.Indb

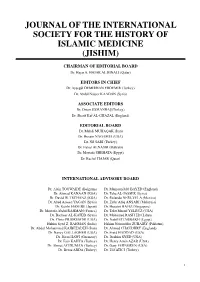

JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) CHAIRMAN OF EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Hajar A. HAJAR AL BINALI (Qatar) EDITORS IN CHIEF Dr.'U$\üHJLLO'(0,5+$1(5'(0,5 7XUNH\ Ayşegül DEMIRHAN ERDEMIR (Turkey) 'U$EGXO1DVVHU.$$'$1 6\ULD ASSOCIATE EDITORS 'U2]WDQ860$1%$û 7XUNH\ 'U6KDULI.DI$/*+$=$/ (QJODQG EDITORIAL BOARD 'U0DKGL08+$4$. ,UDQ 'U+XVDLQ1$*$0,$ 86$ 'U1LO6$5, 7XUNH\ 'U)DLVDO$/1$6,5 %DKUDLQ 'U0RVWDID6+(+$7$ (J\SW 'U5DFKHO+$-$5 4DWDU INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Alan TOUWAIDE (Belgum) Dr. Mamoun MO BAYED (England) Dr. Ahmad KANAAN (KSA) Dr. Taha AL-JASSER (Syra) Dr. Davd W. TSCHANZ (KSA) Dr. Rolando NERI-VELA (Mexco) Dr. Abed Ameen YAGAN (Syra) Dr. Zafar Afaq ANSARI (Malaysa) Dr. Kesh HASEBE (Japan) Dr. Husan HAFIZ (Sngapore) Dr. Mustafa Abdul RAHMAN (France) Dr. Talat Masud YELBUZ (USA) Dr. Bacheer AL-KATEB (Syra) Dr. Mohamed RASH ED (Lbya) Dr. Plno PRIORESCHI (USA) Dr. Nabl El TABBAKH (Egypt) Hakm Syed Z. RAHMAN (Inda) Hakm Namuddn ZUBAIRY (Pakstan) Dr. Abdul Mohammed KAJBFZADEH (Iran) Dr. Ahmad CHAUDHRY (England) Dr. Nancy GALLAGHER (USA) Dr. Frad HADDAD (USA) Dr. Rem HAWI (Germany) Dr. Ibrahm SYED (USA) Dr. Esn KAHYA (Turkey) Dr. Henry Amn AZAR (USA) Dr. Ahmet ACIDUMAN (Turkey) Dr. Gary FERNGREN (USA) Dr. Berna ARDA (Turkey) Dr. Elf ATICI (Turkey) I JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) Perods: Journal of ISHIM s publshed twce a year n Aprl and October. Address Changes: The publsher must be nformed at least 15 days before the publcaton date. All artcles, fgures, photos and tables n ths journal can not be reproduced, stored or transmtted n any form or by any means wthout the pror wrtten permsson of the publsher. -

Music Therapy and Mental Health Mental Health Care and Bimaristans in the Medical History of Islamic Societies

Rüdiger Lohlker (Vienna University) Music Therapy and Mental Health Mental Health Care and Bimaristans in the Medical History of Islamic Societies Even recent studies on the histories of hospitals only have few pages on Islamic hospitals.1 Thus, it is necessary to turn to a thorough study of Islamic hospitals as an important element of a global history of hospitals and health care. There are other names for hospitals in Islamic times, but this study will use the term bīmāristān to identify these institutions. Our focus will be on mental health and bīmāristāns another field still underresearched.2 Recent studies claim that going beyond the classical studies of ideas of medicine and leaving the old paradigms of Islamic exceptionalism behind, would allow for an integration of the study of medicine in Islamic societies into the field of science studies3 and for a better understanding of the institutional contexts of medical practice.4 Understanding the history of Islamic hospitals means turning to pre-Islamic times.5 We could turn to pre-Islamic Arabia6, but more important may be the Eastern part of what was to be the Islamic world. Thus, we will be able to look into the institutional contexts of Islamic medicine7 – and especially its aspects related to mental health.8 1 In numbers: four pages, thus, excluding Islamic institutions from a general history of hospitals (Risse 1999). 2 Thanks to Margareta Wetchy for her valuable comments. Thanks also to the organizers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences of the Maimonides Lectures 2019 in the Austrian city of Krems who gave the opportunity to present a first version of these ideas. -

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin Translated by Liadain Sherrard with the assistance of Philip Sherrard KEGAN PAUL INTERNATIONAL London and New York in association with ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS for THE INSTITUTE OF ISMAILI STUDIES London Contents Transcription xi Foreword xiii PART ONE From the Beginning Down to the Death of Averroes (595/1198) I. The Sources of Philosophical Meditation in Islam 1 1. Spiritual exegesis of the Quran 1 2. The translations 14 n. Shiism and Prophetic Philosophy 23 Preliminary observations 23 A. Twelver Shiism 31 1. Periods and sources 31 2. Esotericism 36 3. Prophetology 39 4. Imamology 45 5. Gnosiology 51 6. Hierohistory and metahistory 61 7. The hidden Imam and eschatology 68 B. Ismailism 74 Periods and sources: proto-Ismailism 74 I. Fatimid Ismailism 79 1. The dialectic of the tawhld 79 2. The drama in Heaven and the birth of Time 84 3. Cyclical time: hierohistory and hierarchies 86 4. Imamology and eschatology 90 n. The reformed Ismailism of Alamut 93 1. Periods and sources 93 2. The concept of the Imam 97 3. Imamology and the philosophy of resurrection 100 4. Ismailism and Sufism 102 m. The SunnI Kalam 105 A. The Mu'tazilites 105 1. The origins 105 2. The doctrine 109 B. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari 112 vii CONTENTS 1. The life and works of al-Ash'ari 112 2. The doctrine of al-Ash'arl 114 C.Ash'arism 117 1. The vicissitudes of the Ash'arite School 117 2. Atomism 120 3. Reason and faith 122 IV. Philosophy and the Natural Sciences 125 1. -

2. Islamic History, Religion & Culture

861-875 H. al-qism 7. min al-juz' 2. 876-890 H. al- qism 8. min al-juz' 2. 891-896 H., ma'a al-fahâris al- qism 9. min al-juz' 2. Fahâris al-a'lâm. Egypt -- Syria -- History -- 1250-1517 2. ISLAMIC HISTORY, RELIGION 137 'Abd al-Ghaffâr, Muhammad (ed.) & CULTURE Al -Majâlis al -Mu'ayyadîyah. 338p Cairo 1994 1,800 138 イスラムの歴史・思想・文化 'Abd al-Hamîd al-Shirqânî & Ahmad ibn Qâsim al- 'Abbâdî Hawâshî al -Shirqânî wa Ibn Qâsim al -'Abbâdî 'alâ Tuhfat al -Muhtâj bi Sharh al -Minhaj. 10 vols. Beirut 2009 repr. 35,400 132 :Islamic law -- Shafiites -- Early works to 1800 Aasi, Ghulam Haider 139 Muslim Understanding of Other Religions: a study 'Abd al-Hayy ibn 'Abd al-Halîm al-Laknawî (m. 1304 of Ibn Hazm's Kitab al -fasl fi al -milal wa al -ahwa' wa h.) al -nihal . xviii,231p New Delhi 2004 81-7435-359-3 'Umdat al -Ri'âyah 'alâ Sharh al -Wiqâyah. 7 vols. ¥1,000 Beirut 2009 978-2-7451-6263-2 20,800 133 :Islamic law -- Hanafites -- Early works to 1800 Abadi, Jacob 140 Tunisia since the Arab Conquest: the saga of a 'Abd al-'Îsâwî, Salâh Hamîd westernized Muslim state . xiv,586p London 2013 Ta'sîl al -Qawâ'id al -Usûlîyah al -mukhtalaf fî -hâ 978-0-86372-435-0 12,743 bayna al -Hanafîyah wa al -Shâfi'îyah . 607p Beirut 2012 :This comprehensive history of Tunisia covers an 978-9933-482-05-3 3,600 essential period in the country's development, from :Islamic law -- Interpretation and construction the Arab conquest of the 7th century to the Jasnime 141 revolution and the fall of Ben Ali's regime. -

Revised Translation of the Chahr Maqla ("Four Discourses") of Nizm-I

) -> I ] E. J. W. GIBB MEMORIAL SERIES VOL. XI. 2 \ 1 .. REVISED TRANSLATION- OF THE ., CHAHAR MAQALA - ("FQUR DISCOURSES") OF NIZAMi-I-'ARUDi ' J OF SAMARQAND, * FOLLOWED BY AN ABRIDGED TRANSLATION OF MIRZA MUHAMMAD'S NOTES TO THE t PERSIAN TEXT BY EDWARD G. BROWNE, M.A., M.B., F.B.A., F.R.C.P. PP.INTED BY THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR THE TRUSTEES OF THE "E. J. W. GIBB MEMORIAL" AND PUBLISHED BY MESSRS LUZAC & CO., '46, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1921 ' t . S . c . * . "E. ?! W. GIBB MEMORIAL" PUBLICATIONS. * t)ZZ> SERIES. (25 works, 37 published volumes.) I. Bahur-nama (Turki text, /ac-simile), ed. Beveridg'j, 1905. ' ; ' Out ofprint. r II. History o i Tabaristan of lion Isfandiyar, abridged transl. Browne, 1905, Ss. ft III, 1-5. History of Rasiili dynasty of Yaman by al-lhaz- 2 raji; I, transl. of Sir James Rediouse, 1907-8, "js. each; Annotations the Arabic text ed. 3, by same, 1908, 55. ; 4, 5, Muhammad 'Asal, 1908-1913, Ss. <each. IV. Omayyads and 'Abbasids, transl. Margoliouth from the % 9 Arabic of G. Zaidqn, 1907, 5^. V. travels of Jbn Jiibayr, Arabic text, ed. de Goeje, 1907, IOJ. VI, 1/2, 3, 5, 5. Yaqut's Diet, of learned men (Irshddu- Arabic ed. 'l-Arib\ text, M argoliouth,,1908-1*9 13 ; 205., 125., ,105-., 15^., 15-r. respectively. VII, i, 5, 6. Tajaribu'1-Umam of Miskawayhi (Arabic text, fac-simile), ed. le Strange and others, 1909-1917, 7^. each vol. VIII. 'MarzuDan-nama (Persian text), ed. -

20 Socrates in Arabic Philosophy ILAI ALON

A Companion to Socrates Edited by Sara Ahbel-Rappe, Rachana Kamtekar Copyright © 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd socrates in arabic philosophy 20 Socrates in Arabic Philosophy ILAI ALON Background, Sources, and Tradition Socrates was embraced by Arab culture in the Middle Ages as the paradigm of the moral sage rather than as a philosopher in the strict sense of the word. His image rested upon two classes of material: Plato on the one hand and subsequent authors on the other. Regarding this first source, there is written evidence for the existence of Arabic translations of some of Plato’s writings, especially the Phaedo (Bürgel 1974: 117, 101), Timaeus, Laches, and Meno, which are quoted especially by al-Biruni (d. 1034) and reported in Abu Bakr al-Razi’s writings, as well as by those of al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik (e.g. 95, 1). Among the second class of materials there may at least be a partial contribution from the Cynic school (Rosenthal 1940: 388), perhaps trans- mitted to the Arab world via Indian sources. Even so, other Hellenistic works cer- tainly found their way into Arabic tradition: Xenophon is quoted as are other authors such as Ammonius and Porphyry; Diogenes Laertius and pseudo-epigraphic writings like Liber de Pomo also served as direct sources for the Arabic Socrates tradition. How- ever, in addition to complete texts it seems plausible that a certain Greek gnomic collection also existed that served the Syrians and/or the Arabs as a source for their knowledge. As viewed from the medieval Arabic perspective, the route of the Socratic tradition went roughly as depicted in fig. -

5. Uluslararasi Islam Tip Tarihi Cemiyeti Kongresi 5Th

5. ULUSLARARASI İSLAM TIP TARİHİ CEMİYETİ KONGRESİ 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE 25-28 Ekim 2010 25-28 October, 2010 ISTANBUL – TÜRKİYE ÖZET KİTABI – ABSTRACT BOOK 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE 25-28 October, 2010, Istanbul - TÜRKİYE Editörler ve Yayına Hazırlayanlar: Prof. Dr. Nil SARI Uzm. Dr. Burhan AKGÜN Dizgi: Burhan AKGÜN - Oğuz BARIŞ Baskı: İ.Ü. Basım ve Yayınevi Müdürlüğü Baskı tarihi: Ekim 2010 Basım Yeri : İSTANBUL - TÜRKİYE 2 5.ULUSLARARASI İSLAM TIP TARİHİ CEMİYETİ KONGRESİ 25-28 Ekim 2010, İstanbul – TÜRKİYE SÖZLÜ BİLDİRİLER ORAL PRESENTATIONS 3 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE 25-28 October, 2010, Istanbul - TÜRKİYE 4 5.ULUSLARARASI İSLAM TIP TARİHİ CEMİYETİ KONGRESİ 25-28 Ekim 2010, İstanbul – TÜRKİYE THE ROLE OF RASHID AL-DIN FAZL ALLAH HAMADANI IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF MEDICINE DURING THE ILKHANID ERA Javad Abbasi, Iran Khaja Rashid al-Din Fazl Allah is an outstanding administrator, physician and historian who had a main role in the renewal and continuity of Iranian society in the Ilkhanid period. His efforts covered many aspects. Two of them were science and social welfare. Rashid al-Din who joined the Mongol (Ilkhanid) court as a physician, attempted to develop medicine in different ways. He considered other nations' inheritance like Chinese medicine (Tebb Ahl Khata). On the other hand, as a powerful and influential administrator and also a rich charity man, he constructed and patronized some medical centers and established courses to train young physicians. -

Hans Daiber, New Manuscript Findings from Indian

New Manuscfipt Findings from Indian Lrbraries fu HansDaiber In the courseof the Islamizationof India sincethe collection originally belonged to Sir Sayed Ahmad 2nd.8th centuryt many Islamic collegeshave been Khan who foundedthe Universityin 1877.His collec- 'Lytton founded there. The history of thesecolleges and their tion has been enlarged by the Collection' 'University activitiesare not yet known2. Their glorious past is which is today calledthe Collection'.Be- testified by an immense number of manuscripts in sides this collection there are eleven other big col- Arabic, Persian and Urdu, many of which can be lectionswhich were donated": 1) the Abdu'l Hayy tracedback to the time of the greatmoghuls;they were Collection; 2) the Abdu's Salárn Collection; 3) the copied in the early 1l,l7th century,but also in the Àftab Collection: 4) the Ahsan Collection; 5) the ll lSth and l3 l9th centuries. HabibganjCollection; 6) the Jau'aharMuseum; 7) the From these manuscripts only a small portion has Munrr Álam Collection; 8) the Qutbu'd Din Collec- been describedin catalogues.Even the number of tion: 9) the Shiftá Collection: 10)the Subhàn Alláh Indian libraries with manuscript collectionsis sti11 Collection:11) the SulaymánCollection. unclear: the enumeration of Islamic manuscript li- Among these only the Shiftá Collection and the brariesin the survevsof A. J. W. Ht-lsrt.,rr3 and Fu,rr Ahsan Collectionhave been described in cataloguesl2. SEzctNais not at all complete.E'"en the comprehensive Both collectionscontain besidesPersian mss.. which Handbook o.f Librurie.s.Art'hive.s und Infnrrnation C'en- have the upper hand, respectively82 and 79 Arabic tres in India which was published in 1984-5in New mss. -

The Medical Response to the Black Death Joseph A

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2015 The medical response to the Black Death Joseph A. Legan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the Bacterial Infections and Mycoses Commons, European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Medical Humanities Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Legan, Joseph A., "The medical response to the Black Death" (2015). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 103. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/103 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Medical Response to the Black Death _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Joseph Andrew Legan May 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of History, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: John Butt, Ph.D., Philip Frana, Ph.D., Professor, History Interim Director, Honors Program Reader: Alison Sandman, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History Reader: Timothy Fitzgerald, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, History Table of Contents List of Figures 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Biomedical Context 6 The Black Death in Europe 10 The Black Death Outside of Europe 20 The Medical Response in Europe 25 The Medical Response in the Middle East 36 Other Responses to the Plague 47 Effect on Medicine 53 Conclusion 59 Appendix 62 Annotated Bibliography 67 2 List of Figures 1.